The language used in the cockpit sounds technical and only aviation professionals understand it. Pilots communicate with each other and air traffic control in English, regardless of their own native language or any other languages they speak.

Aviation English is in some ways a separate language compared to the one spoken on the ground. Therefore, even native English speakers have to learn it. What makes it so special?

English for flight safety

Aviation English has been the de facto international language of civil aviation since the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) recommended English to be universally used for “international aeronautical radiotelephony communications” in 1951.

Why was English chosen to be the language of the sky? This decision was related to the fact that English-speaking countries dominated the design and manufacturing of aircraft, as well as much of their operations. Although, it was just a recommendation by ICAO, English was widely accepted in aviation.

Speaking the same language for pilots, crew and air traffic control is the core factor for aviation safety – miscommunication could become one of the reasons why some aviation accidents may happen. One of the aviation regulation-changing accidents happened in Tenerife in 1977.

It had a lasting influence on the industry, highlighting, in particular, the vital importance of using standardized phraseology in radio communications. Cockpit procedures were also reviewed, contributing to the establishment of crew resource management as a fundamental part of airline pilots’ training.

Language requirements for pilots

In 2001, ICAO determined English as the standardised language of air transport. Following that, ICAO published a directive stating that all aviation personnel, including pilots, flight attendants and aircraft controllers, must pass an English proficiency test and meet the requirements. Before that, the language skills were not checked in a standard way.

Aviation English tests are designed to check and evaluate aviation specialists, language speaking and listening skills. To make the language skills evaluation standardized, ICAO created language proficiency scale from 1 to 6 with the guidelines for pronunciation, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, interaction and structure.

Those, who want to be pilots and apply for aviation studies, need to make sure their language skills meet at least the ICAO Level 4 requirements for the English language. It means that a pilot is expected to pronounce words clearly, although stress, rhythm, and intonation may be influenced by their native language.

Nevertheless, even if English is a pilot’s second language, their vocabulary range and accuracy must be sufficient to communicate effectively on common, concrete, and work-related topics. Grammar is not forgotten in the test, thus a pilot is expected to creatively use well-controlled basic sentences and grammatical patterns.

Aviation English – code language

When pilots and air traffic controllers communicate, they use special aviation terminology, speak in a technical manner and this makes their language sound like a special code. This code does not change, whether the plane flies over London, Istanbul, Hong Kong or Brazil and connects to the local air traffic control tower.

Have you heard “wilco”, “approach” or “pan-pan” in the movies about aviation? They are real and used daily in the cockpit procedures.

The language of aviation consists of a mix of professional jargon and traditional English. Aviation English has a special alphabet which makes spelling on radio connection easier-to-understand and approximately 300 aviation terms. Every pilot must know all of them.

Learning how to speak on aircraft radio starts with phonetic alphabet and memorizing a large number of three-letter abbreviations. Many of these were created in the days of Morse code when radio messages needed to be as short as possible.

Although learning to understand and speak the code pilots speak may be the most challenging aspect of pilot studies, it is crucial to the profession.

Aviation alphabet

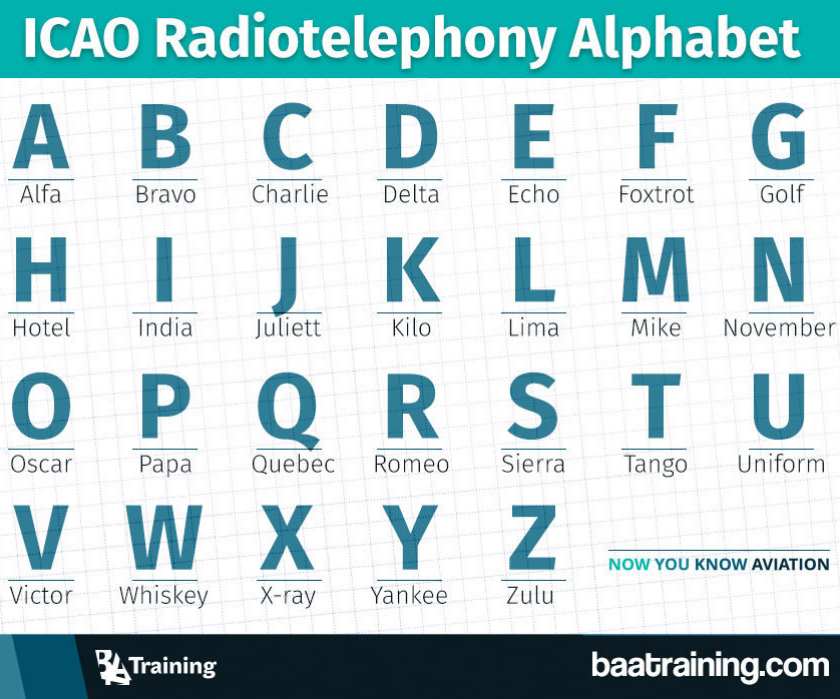

The ICAO created the International Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet, tied it to the English alphabet, to ensure that letters are properly pronounced and understood by air traffic controllers and pilots around the world, regardless of what languages are spoken.

The ICAO alphabet is used to avoid mistakes caused by letters and numbers that sound similar, for example, b and d, m and n. This is the reason why a pilot would read the aircraft number “LY FTN” as Lima – Yankee – Foxtrot – Tango – November.

Notably, there are some variations of the ICAO alphabet – outside North America, some pilots use the non-English spelling Alfa (instead of Alpha) and Juliett (instead of Juliet). These variations were created as some non-English or non- French language speakers may not pronounce “f” when it is spelled “ph”. The extra T is added to Juliet because in French a single T at the end of a word is silent.

Standard phrases

The special alphabet is not the only aviation English feature that differs from the traditional language. Besides the alphabet, pilots learn the standard aviation phraseology. As mentioned earlier, they have to remember the meaning of around 300 standard phrases and special terms. Learn the meanings of the most popular and most important phrases.

Approach: Coming to land.

Affirm: Contrary to popular belief, pilots do not say “affirmative” when they mean “yes” – the correct term is affirm, pronounced “AY-firm”.

Deadhead: This refers to a member of the airline crew who is travelling in a passenger seat.

Mayday: This is the one nobody wants to hear. It does not appear among the most common ones but it probably is the most important. It is a distress call for life-threatening emergencies, such as complete engine failure. It comes from the French “m’aidez” (“help me”). Pilots must say it 3 times at the beginning of a radio call.

Pan-pan: The next level of emergency down from mayday, it’s used for situations that are serious but not life-threatening. It originates from the French word “panne”, meaning breakdown. You repeat it three times: “pan-pan, pan-pan, pan-pan”.

Roger: This means “message received”, but it doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll comply.

Standby: This means “please wait” and this is usually said when an air traffic controller or a pilot is too busy to take a message.

Wilco: An abbreviation of “will comply”, it means the pilot has received the message and will comply.