In 2022, I published a short paper on the construction of the Beatty-Michigan codex of the Pauline epistles (P46, TM 61855). I suggested that the surviving page numbers in the codex might not be an entirely reliable guide to the original size of the single quire that makes up the codex (I had noticed that some other better preserved single-quire papyrus codices were not symmetrical in terms of numbered pages in the two halves of the codex).

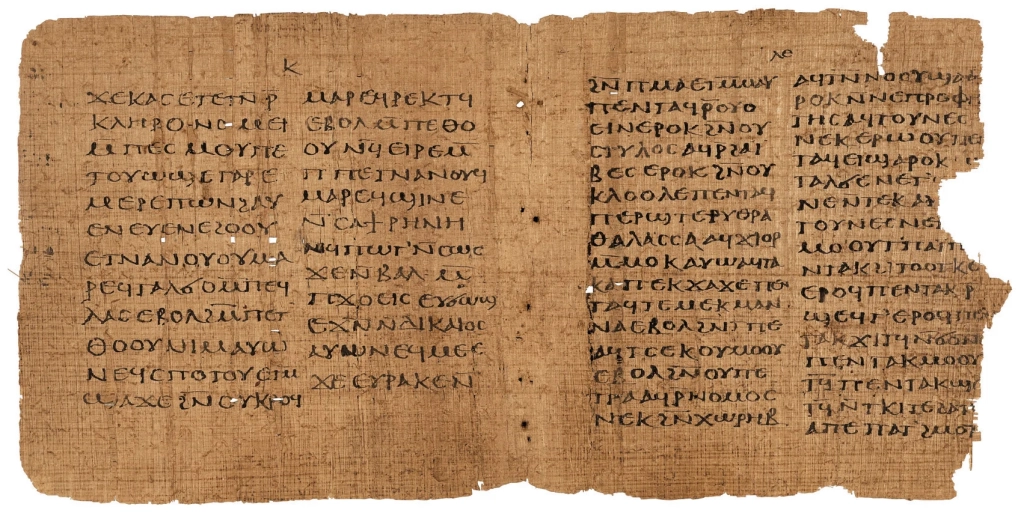

I realized after publication that I had not noted an additional fact relevant to the discussion: Early codices, even single-quire codices, can have multiple sequences of page numbers. I pointed to the Crosby-Schøyen codex (TM 107771) as an example in a subsequent post.

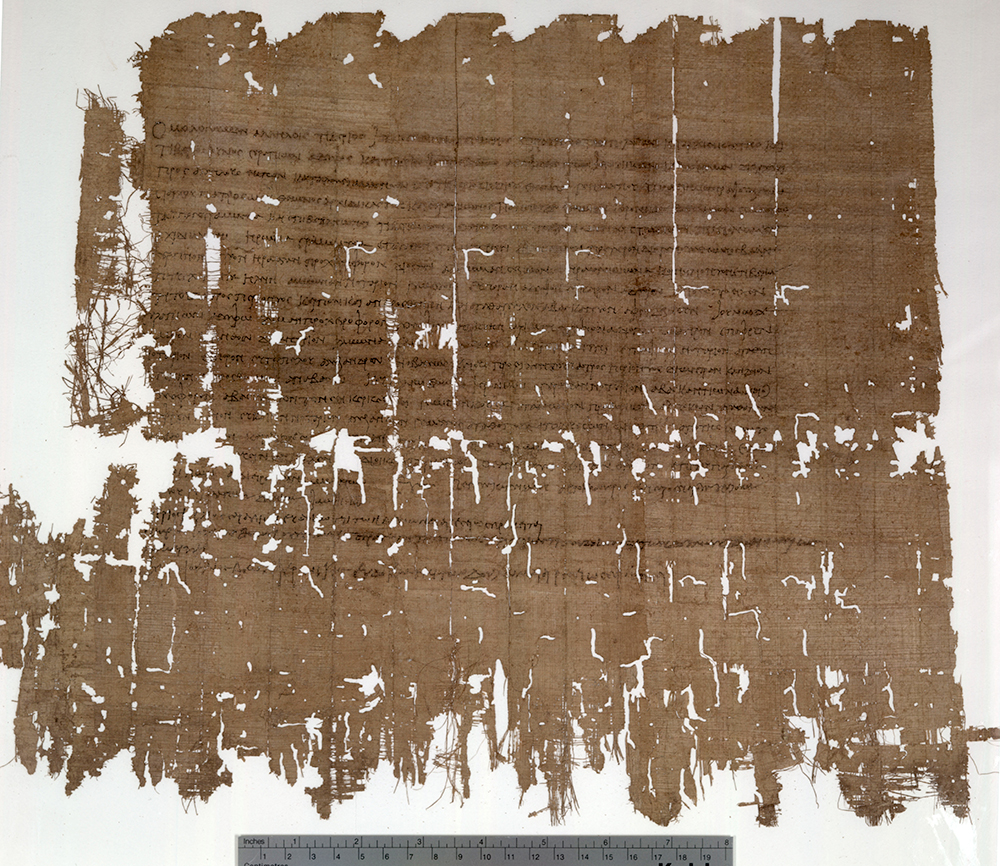

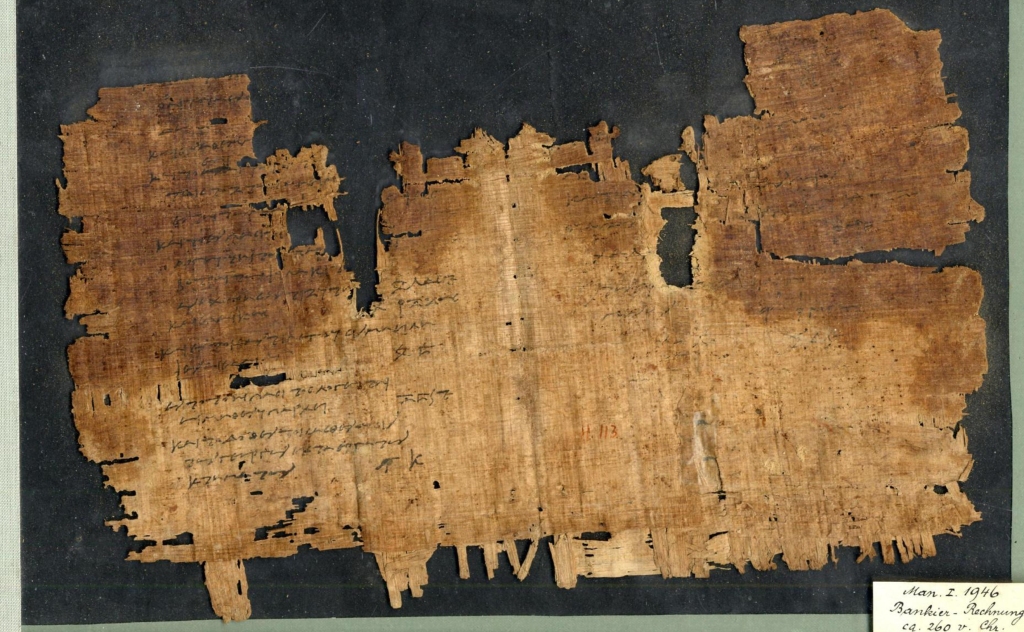

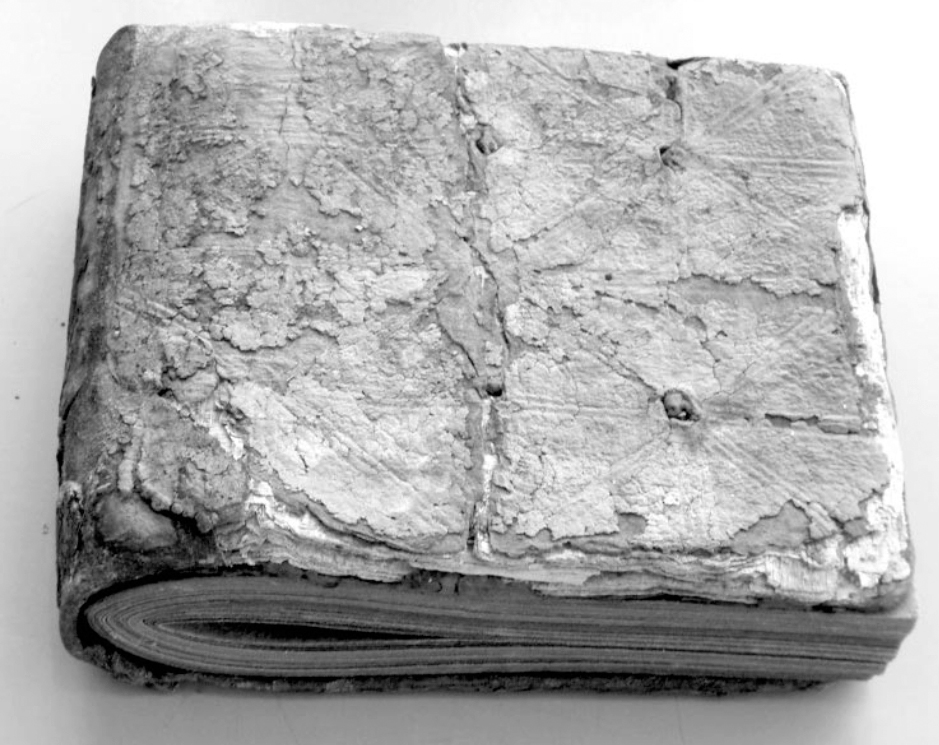

Now, I follow up with another addendum. In the original article I used the Berlin Akhmimic Proverbs codex (TM 107968) as an example of a single-quire codex in which the outer folia of the quire were incorporated into the cover, relying upon the conservator Hugo Ibscher’s description of the book:

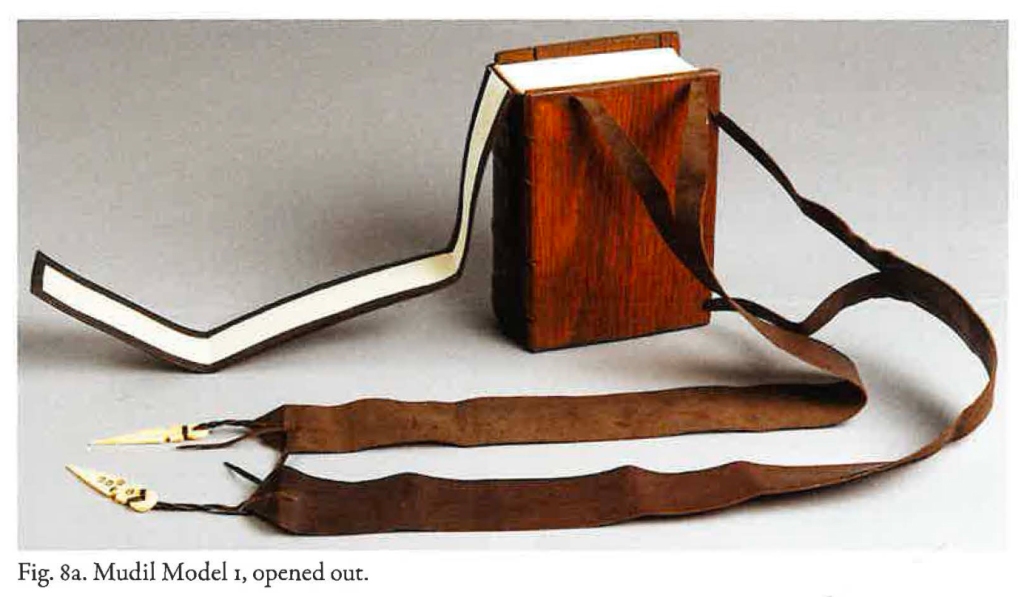

“The Berlin Akhmimic Proverbs codex presents further interesting evidence. Hugo Ibscher noted that the outermost folia of this single-quire codex were incorporated into the leather cover of the codex along with waste papyrus to help stiffen the cover.”

I added a footnote to this sentence expressing some caution about this interpretation of Ibscher:

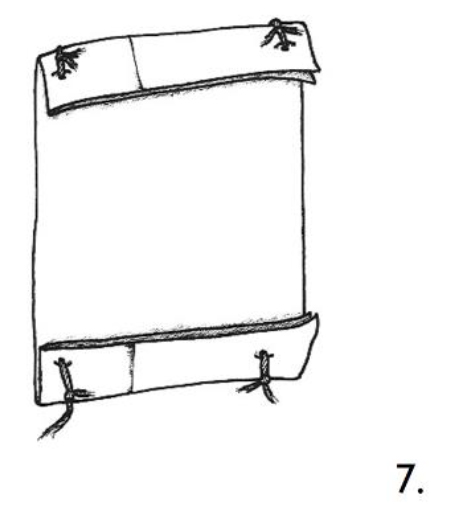

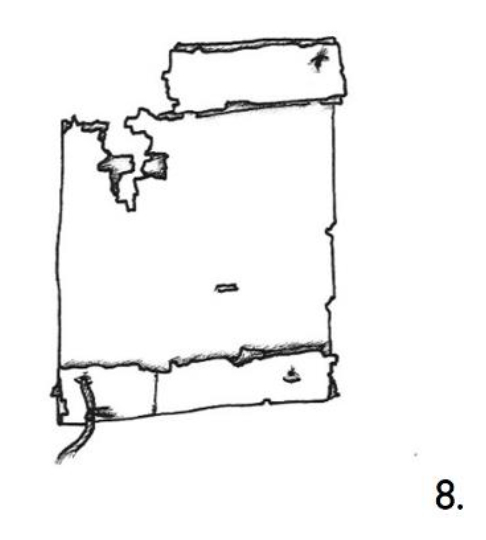

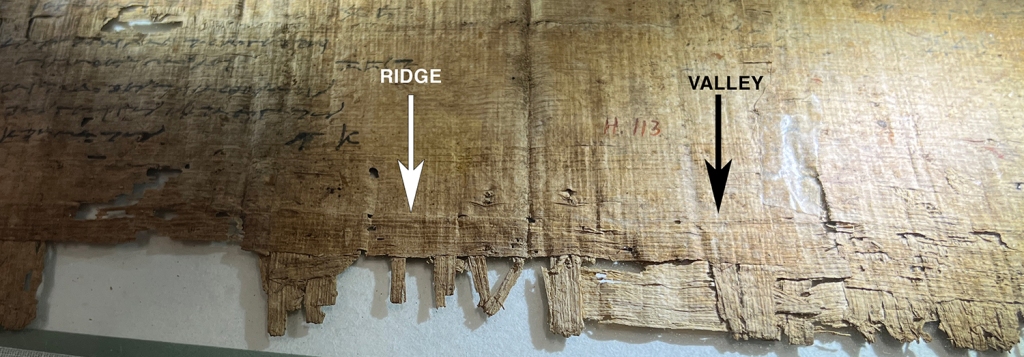

This is at least how I understand Ibscher’s somewhat confusing description: “The cover of the book consists of 6 to 8 layers of papyrus, which, when glued on top of each other, resulted in a strong cardboard. The outer sheets of this cardboard contain remains of Greek writing, while the inner ones are apparently blank. It fits well with this that from the first papyrus roll, before the surviving sheet 1 of the codex, four more sheets have been taken from the first papyrus roll [from which the bifolia were cut] that are not found in the codex and were probably used to strengthen the book cover and were bound through at the same time” (Hugo Ibscher, “Von der Papyrusrolle zum Kodex,” Archiv für Buchbinderei 20 [1920] 21–40, at 39: “Der Buchdeckel besteht aus 6 bis 8 Papyruslagen, die übereinandergeklebt eine starke Pappe ergaben. Die äußeren Blattlagen dieser Pappe enthalten griechische Schriftreste, während die inneren anscheinend unbeschrieben sind. Hierzu paßt es gut, daß aus der ersten Papyrusrolle, vor dem erhaltenen Blatt 1 des Codex, noch vier Blätter entnommen sind, die sich im Kodex nicht vorfinden und wahrscheinlich zur Verstärkung des Buchdeckels verwendet und gleich mit durchgeheftet wurden”). I take heart from the fact that Theodore C. Petersen showed a similar understanding: “The papyrus boards of the binding were found by Dr. Ibscher to have been built up of six to eight papyrus leaves pasted one over the other. Several of the innermost of these were found to have been sewn as part of the original codex, i.e., as its outermost sheets.” See Theodore C. Petersen, Coptic Bookbindings in the Pierpont Morgan Library (ed. Francisco H. Trujillo; Ann Arbor: Legacy, 2021) 430. It is unclear how common this type of construction was among single-quire codices. I know of no other documented examples. J.A. Szirmai, citing Ibscher’s “Der Kodex,” mentions another alleged example of this phenomenon, but he has misread Ibscher’s reference, which is almost certainly to the Berlin Proverbs codex (Szirmai, The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding [Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999] 12).

I was a little unclear on what Ibscher meant by “und gleich mit durchgeheftet wurden.” And I probably should have given Ibscher’s reference from “Der Kodex” in full. The context there is a discussion of single-quire codices. Ibscher does not specifically name the Proverbs codex (which is why Szirmai, I think, misinterpreted him), but it must be the Proverbs codex that Ibscher had in view:

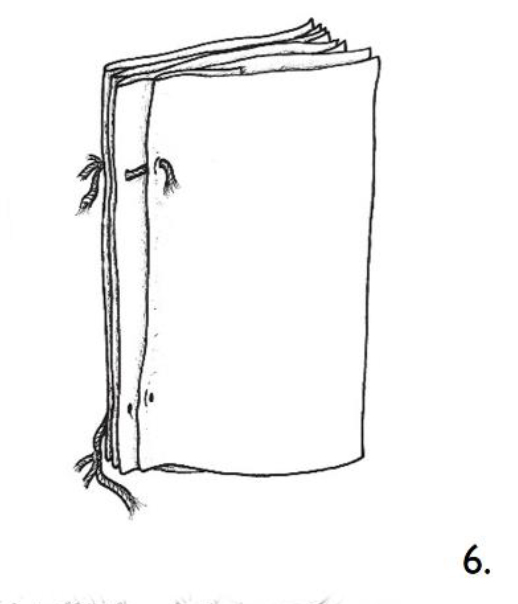

“In one of these early codices I was able to make the interesting observation that the six outer bifolia were left blank. They were firmly attached to the quire by stitching, then glued together and now also served as a book cover, which was covered with leather.”

“Bei einem dieser frühen Kodizes konnte ich noch die interessante Beobachtung machen, daß die sechs äußeren Doppelblätter unbeschrieben gelassen wurden. Sie wurden mit der Lage durch die Heftung fest verbunden, dann zusammengeklebt und dienten nun zugleich als Buchdeckel, der mit Leder überzogen war.”

Now, I am happy to report that another passage by Ibscher confirms this understanding of the construction of the Proverbs codex in no uncertain terms. While looking up some information about the Medinet Madi codices, I came across this note by Ibscher specifically in reference to the Proverbs codex (Ms. or. oct. 987):

“The Coptic papyrus codex of the Berliner Staatsbibliothek, which was still bound when I received it for conservation, consists of 40 bifolia and some stubbed bifolia, while the 6 outermost bifolia were glued together to form the book cover.”

“[D]er koptische Papyruskodex der Berliner Staatsbibliothek, der noch im Einband saß, als ich ihn zur Konservierung erhielt, umfaßt 40 Doppelblätter und einige Einzelblätter, während die äußeren 6 Doppelblätter zusammengeklebt den Buchdeckel ergaben.”

It’s good to have Ibscher’s view of this matter fully clarified.

Bibliography:

Ibscher, Hugo. “Die Handschrift.” Pages v–xiv in Hans Jakob Polotsky and Alexander Böhlig, Manichäische Handschriften der Staatlichen Museen Berlin: Kephalaia, 1. Hälfte (Lieferung 1–10). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1940.

Ibscher, Hugo. “Der Kodex.” Jahrbuch der Einbandkunst 4 (1937) 3-15.

Nongbri, Brent. “The Construction and Contents of the Beatty-Michigan Pauline Epistles Codex (P46).” Novum Testamentum 64 (2022) 388-407.