Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s insertion of pantheism into politics makes the state into the church and creates a coercive political religion in the service of messianic purposes—as seen during the French Revolution. Overcoming this pantheistic desire for ultimate harmony is an important step in the quest for political rationality.

In 1749, a solitary man walked out of the city of Paris toward the village of Vincennes. As he moved along, reading, something happened to him that would shape the trajectory of modern history into our own times. What transpired suggests that the dangerous side of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, from the Christian point of view, was not so much the liberation of “the secular.” Rather, it was the insertion into modern politics of an old religion: that of pantheism and the longing for this-worldly wholeness. What happened that afternoon started a chain reaction of conflict not only with Christianity as a rival religion but with political rationality itself.

In 1749, a solitary man walked out of the city of Paris toward the village of Vincennes. As he moved along, reading, something happened to him that would shape the trajectory of modern history into our own times. What transpired suggests that the dangerous side of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, from the Christian point of view, was not so much the liberation of “the secular.” Rather, it was the insertion into modern politics of an old religion: that of pantheism and the longing for this-worldly wholeness. What happened that afternoon started a chain reaction of conflict not only with Christianity as a rival religion but with political rationality itself.

The man was Jean-Jacques Rousseau and what occurred was an ecstatic experience so powerful that he threw himself down under a tree. He “there passed a half hour in such agitation that on rising,” he wrote in his second letter to Malesherbes, “I found the whole front of my shirt wet with tears, without having been conscious that I had shed them.” These intense minutes, interrupting his walk, were prompted by his reading of the headline for an essay competition: “Has the restoration of the sciences and arts contributed to the purification of morals?”

The question suddenly ignited Rousseau’s mind and overwhelmed his soul. From the moment he read those words, he recalled, “I beheld another world and became another man.” Perhaps humans are naturally good? Perhaps evil proceeds not from the heart of man but from the constraint and competition of an artificial civilization? Maybe we need to return to our natural simplicity in order to be whole? Dazzled by a thousand sparkling lights as lively ideas crowded his mind, he felt giddy and intoxicated. With difficulty breathing and violent palpitation of the heart, a vision of the meaning of human life revealed itself to Rousseau. His life—and modern history—would never be the same.

Rousseau experienced what the ancients called “poetic fury,” an intense moment of creative energy. It propelled his major writings for more than a decade. These works—such as Julie (1761) or Emile (1762)—caused a revolution in Western literature, morality, social relationships, education, and politics. Rousseau’s deepest theme was a new gospel: Happiness comes from following the divine instincts of our hearts to restore communion with ourselves and the cosmos. Rousseau’s new religion was grounded in emotional pantheism.

Pantheism in general holds that God and the world are one reality. It calls people into spiritual union with nature as a total, all-embracing reality. Within this worldview, Rousseau sought emotional wholeness. He would escape his personal distress, for example, by heading out into nature on solitary walks. He gave himself over to sentiment. From there he would try to lose himself in contemplation of all the beings of nature, the universal system of things, and the incomprehensible being who embraces all.

This worldview took root among certain nineteenth-century German philosophers, French socialists, and English poets. In the following century, pantheism had consequences for progressive politics. Richard Weikart’s 2016 book Hitler’s Religion argued Adolf Hitler followed the pantheist belief that nature is God. One serves this God by listening exclusively to the scientists, to the “political biology” of the day, and by following the “laws of nature” controlling social degeneration and progressive renewal.

More recently, one sees the influence of pantheism in the United States. This is due to a tendency identified by Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America. As equality among people in general is emphasized, individuality is ignored, and focus is placed on “the people” collectively. “The idea of unity so possesses man and is sought by him so generally that if he thinks he has found it, he readily yields himself to repose in that belief,” he wrote. The pantheist mind, Robert J. Delahunty noted in an online article on Tocqueville and pantheism, “encloses” God and the world in a single entity—forming a “cosmic egalitarianism.”

Thus, it is not surprising that pantheism “has been Hollywood’s religion of choice for a generation now,” New York Times columnist Ross Douthat wrote in his 2009 movie review of Avatar. The World Pantheist Movement (started in 1997) connects pantheism to activist environmentalism, giving it theological heft. By recognizing ourselves as simply part of a divine world we can eliminate war and environmental degradation. Pantheism “expands the democratic franchise… to include other species,” John Grula wrote in his 2008 article “Pantheism Reconstructed.” And progressive activists today like Patrisse Cullors think in overtly pantheistic terms: “I don’t believe spirit is this thing that lives outside of us dictating our lives,” Ms. Cullors said in a 2015 interview, “but rather our ability to be deeply connected to something that is bigger than us. I think that is what makes our work powerful.” This something “bigger” is the ground of being, Mother Earth-Nature, the vehicle of god-consciousness and cosmic power inside oneself.

The significance of Rousseau is not that he somehow caused these later developments. There are multiple gateways to pantheism. Rather, it is that Rousseau’s example first connected politics to the pantheistic longing for ultimate harmony. This sheds light on where that link can lead.

On October 15, 1794, the people of Paris transferred the body of Rousseau to the Panthéon, underscoring the link they saw between Rousseau and the French Revolution. French state religion—with overt pantheistic themes—had aggressively replaced Catholicism by that time. “It is to Rousseau,” the president of the Convention said on the occasion, “that we owe this salutary regeneration which has caused such fortunate changes in our morals, in our customs, in our laws, in our minds, and in our habits.”

What sort of regeneration? In Rousseau’s political writings, “virtue” meant putting what he called the “general will” above one’s own individual will and even conscience. Self-interest is bad. Partisanship and “partial associations” of citizens mar the harmony of the whole. As mystics seek ultimate fulfillment in giving themselves completely to God, so Rousseau counseled giving oneself unreservedly to the community, thus forming a union “as perfect as possible.” Embodying this general will of the community, the state could change human nature (redeem it) through legislation, making its members unselfish and concerned for the whole. The always “politically correct” general will would thus create a perfectly unified democracy, incorporating citizens into the mystical body of the state. This was political pantheism and a recipe for “totalitarian-democracy” as it actually emerged in the 1790s.

Rousseau rejected any attempt to divide political authority, implying that the separation and balance of powers were impossible routes to social harmony. The very clashes between factions that Rousseau condemned as paralyzing “partial associations,” however, were celebrated by James Madison in the United States. Rival “factions,” as he called them in Federalist Paper 10 (1787), would help preserve freedom. Madisonian constitutionalism limited democracy. It attempted to institutionalize the constraints of justice and the rule of law on majority rule, Paul DeHart wrote in his online essay “Madisonian Thomism.” This American approach was more in line with that of the medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas: Law proceeds from reason, not from will. In Rousseau, however, whatever the people will is law. This view was enshrined in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (1789) at the very outset of the French Revolution, in article 6: “Law is the expression of the general will.” The people are god. Limited democracy in the United States recognized the prerogatives of God, churches, and culture; Rousseau’s kind of democracy recognized no such limits. These two clashing political legacies of the Enlightenment still shape our landscape today.

In his quest for this-worldly wholeness, Rousseau desired to rid the body politic of contradictions. This meant he deplored the effect of Christianity in separating Caesar and God. Divided allegiances interrupted true communion of persons, he felt. In the ancient world of paganism, and in Muhammad’s religion, Rousseau wrote admiringly in The Social Contract, state and church constituted one powerful unity—the pantheistic impulse. He advocated a return to this ideal.

This was the ancient myth of the divine state born again. As Pope Benedict XVI said in his homily “Biblical Aspects of the Theme of Faith and Politics,” “man cannot do without the totality of hope.” If the horizon of hope extends no further than the sky above us, however, then to serve the state is to serve “God.” There are no other priests than magistrates, Rousseau noted, no other pontiff than the one who embodies the pure and unified democratic people. This made the state into the church and created a coercive political religion in the service of messianic purposes—as seen during the French Revolution.

But such exalted salvific goals can in reality be realized only beyond the sphere of political action, Pope Benedict XVI noted. That is why Rousseau’s pantheistic “mythological politics” made reasonable politics difficult or impossible. Reasonable politics in necessarily limited politics rooted in concrete, human reality. This requires honesty to “accept man’s limits,” Pope Benedict XVI said, and to do “man’s work within them.” True morality in politics is a compromise between different interests amid the messy realities of partisanship, not rigid adherence to one’s ideology of human regeneration. Overcoming the pantheistic desire for ultimate harmony in this world is an important step in the quest for political rationality.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

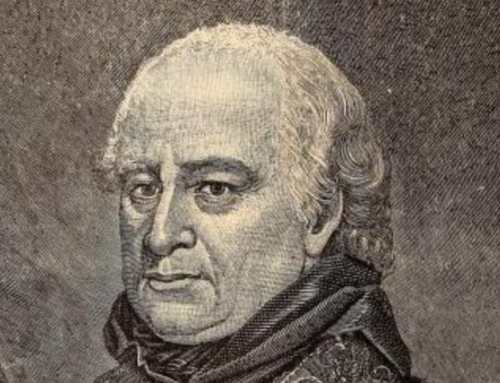

The featured image is a detail from “Festival of the Supreme Being” (1794) by an unknown artist and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. It has been brightened for clarity.

This was a great article! History can reveal so much about our current times, and be a warning of what may happen if we stray.

Was Rousseau’s pantheism influenced by Kant’s philosophy of the categorical imperative?