There has been a sea-change in migration trends in Europe. After decades of losing population to the West, Eastern Europe suddenly found itself on the receiving end of a large tsunami of people, migrating back to their home countries in the wake of the pandemic.

The combination of a sharp contraction in consumption, widespread business decline, shutdowns of large swathes of the economy, and last but not least, a health crisis, which mandates quick access to health services, has led many migrants to conclude that the safest and most sensible decision would be to return home to their birthplaces. This decision is also underlined by emotional reasons, which cannot be overstated - the need to be with one's relatives, in a place where one has built up a social network that can be a source of mutual support during a crisis.

This trend has the potential to transform some places demographically as well as socially and economically. So how many people returned to Bulgaria and how many will stay?

There is a report on the issue, backed by the European Council of Foreign relations and 'Konrad Adenauer Stiftung", which tries to establish the scale of return migration to the country. It has some pretty interesting trends in it.

The numbers

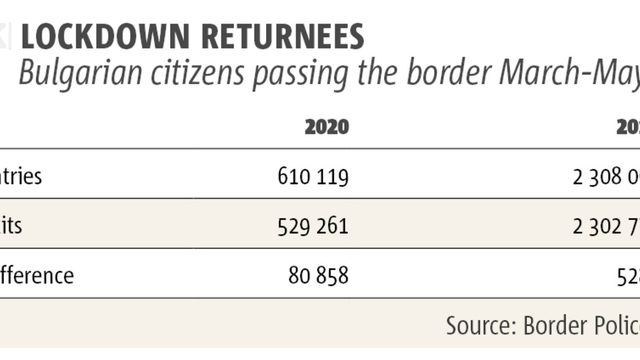

The report looks at the stats in the period March-May 2020. March was the starting point of the crisis - Bulgaria was one of the first European countries to issue a state of emergency and a lockdown on March 13, 2020. Officially, the state of emergency continued until May 13, although most restrictions began to be officially lifted on May 3.

In the mentioned period, over 600 thousand people entered the country. Of course, those are not all returnees. Yet it has to be noted that the number of entrants was 80 000 people higher than those who left the country in the same period. For comparison - in 2019, which saw four times the number of travelers, this difference is about 5 thousand people. Moreover, in two of the months in 2019 - March and May, more people left Bulgaria than entered. In 2020, in each of the three months, the number of entrants is much higher than the number of those leaving.

For the purposes of the study, it was assumed that anyone with Bulgarian citizenship who returned to the country in that period, during the worst part of the crisis, and faced a mandatory 14-day quarantine and huge travel restrictions, did not travel for leisure, tourism or business.

The strict provisions, associated with tracing and containing the coronavirus, set a new standard for accounting for the entrants into the country. Thus, starting from the middle of March, the border and health authorities began registering every entry into the country, regardless of whether it came from the EU or not. In some cases, the entrants are even traced to their final destination because of the quarantine rules. This created a unique dataset unavailable before or after that.

Where did they go

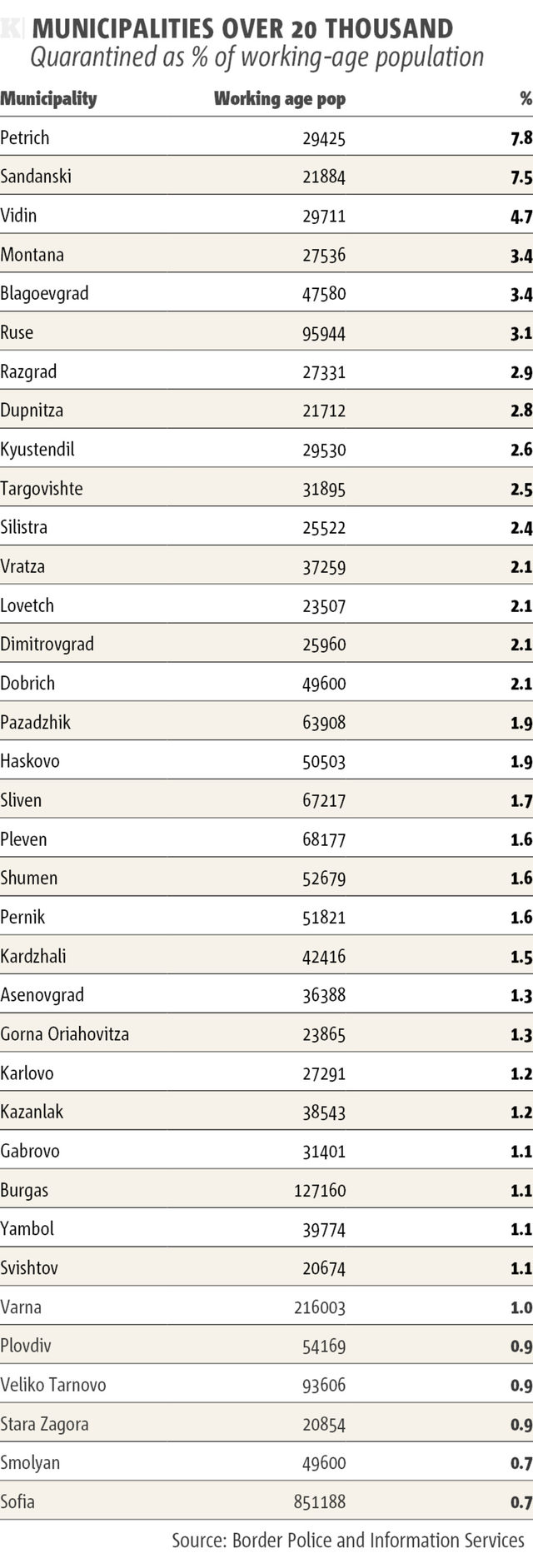

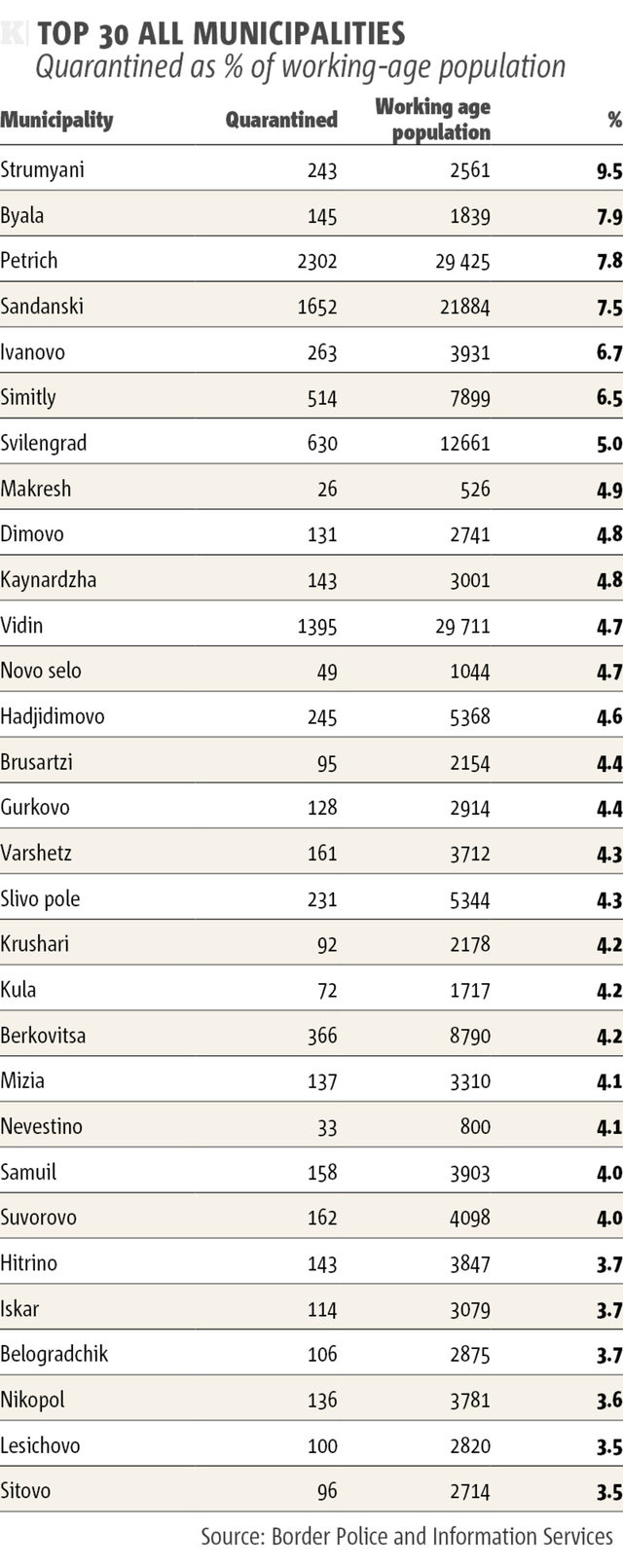

This dataset allowed for detailed research on the municipal level. Comparing the number of returnees quarantined at different municipalities to the working-age populations there points to some cities with a significant percentage share of returnees. In Petrich for example, this share is 9%, in Vidin, it is 4.5%, in Montana, Ruse and Blagoevgrad - around 4%. Given that the quarantined for the studied period account for just under half the total number of entrants into the country, it is logical to assume that the total amount of repatriates to these locations represents a larger percentage share than the stated data.

Three cities that are situated near a border stand out - Petrich, Sandanski and Svilengrad. All three are ranked high both in real terms and as a percentage of the population, whether in the overall ranking or in that of cities with over 20 000 people (excluding Svilengrad due to the smaller population). However, more than one explanation applies here. All three cities have long been losing labour to nearby Greece and Turkey, mostly in the fields of agriculture and tourism. On the one hand, it is perfectly understandable that at the first signs of serious health and economic crisis affecting those spheres, much of this labour force returned quickly to their native places. On the other hand, it is not impossible that these cities could have been used as a "quarantine zone" for those returning from abroad by car. However, such information cannot be found officially; moreover, since the authorities allowed the quarantine to take place after reaching one's final address, this is less likely.

It is impossible to draw definitive conclusions from this dataset without further research and information. It is, however, important to note that these are some of the places where the greatest outgoing migration has occurred in previous years. Cities from the three parts of the country that have suffered the most from the outflow of human capital - the area Ruse -Razgrad- Silistra, the line Kyustendil-Blagoevgrad-Petrich and Northwestern Bulgaria - all make it into the top 10 of cities with a population of over 20 thousand people, where those quarantined lead in terms of percentage of the working-age population. This cannot be explained solely by the fact that these cities shrunk due to depopulation and thus, the percentage of returnees is higher. For example, more people were quarantined (i.e. returned from abroad) in real terms in Ruse than in Varna, which is twice the size of Ruse. There are more quarantined individuals in Vidin than in Bourgas, which is five times bigger.

Is this going to last?

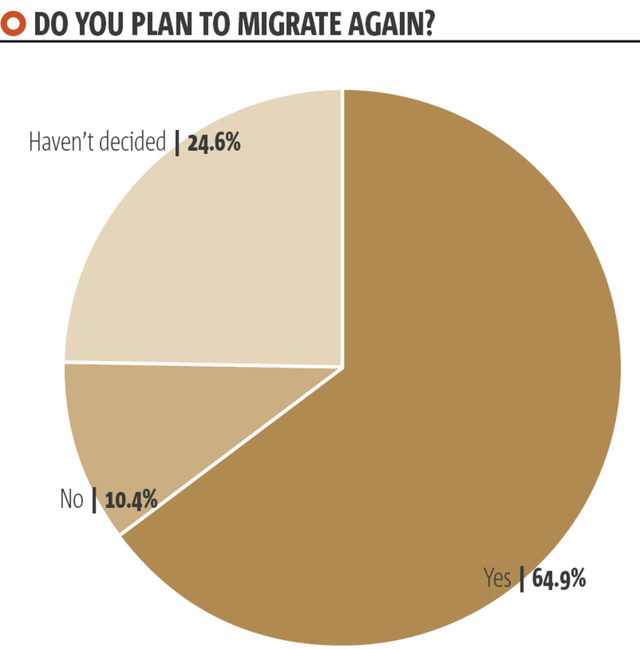

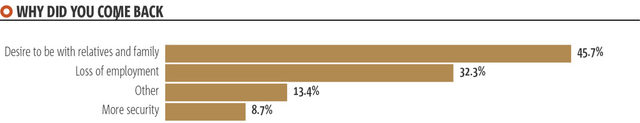

The authors of the report carried out an online survey with people who returned after a prolonged period abroad. The results show that the two leading reasons for repatriation are "the desire to be with relatives" (46%), or "job loss" (32%). 10% of respondents stated that they would not be returning abroad after the COVID crisis is over, whereas 25% had not decided yet. Within the group that has spent over one year abroad, these shares are respectively 19% and 47%. The factors their decision hinges upon are finding well-paid work here in Bulgaria, corruption, the COVID-19 crisis, finding work abroad, and the social and urban environment.

The current repatriation trend is probably going to be a temporary phenomenon in many places. The fundamental reasons why people choose to migrate have not changed substantially due to Covid-19. Unless the pandemic leads to long-term restrictions and uncertainty for health care systems and economies, one would expect the current migration flow to reverse its direction and recover its pre-pandemic volume over the next 2-3 years.

Yet the research clearly shows the opportunity for Bulgaria and specific places to retain some of that talent - 10% or even more.

Several factors could help make the current trend a more sustainable and important event for Eastern Europe.

First, the effects here are much stronger and visible. Discounting regions with active military conflicts, Eastern Europe has long been the world's most affected in terms of population decline and emigration. It is also the only region that has reported population decline for three consecutive decades.

Since 1990 Bulgaria has lost 1.3 m people or around a fifth of its population. Lithuania has lost a quarter of its population, Romania - close to 18%, and Hungary - 7%. This trend is unlikely to change. According to the UN's demographic projections for 2100, only 4 out of the top 20 countries with the fastest shrinking populations are outside Eastern and Central Europe.

The return of such sizable groups of people to economies that have been suffering from population decline for so long is going to be a markedly different experience.

Second, economies in Eastern Europe have the capacity to at least partially accommodate this return wave. While many of the Asian and Latin American economies suffer from an oversaturation of the workforce or from insufficient economic activity to support the new flow of people, over the past few years Eastern Europe has been suffering from the opposite problem. Labour shortages and associated wage hikes were evident everywhere in the region.

The impact of the coronavirus notwithstanding, there are no structural reasons for these economic trends to change. On the contrary, some business fields are already undergoing a process of moving production capacities and shortening supply chains, which should make Eastern Europe one of the major winners globally. Thus, labour demand is going to increase, rather than decline.

Third, the European Union is the key difference between these regions and others. A large share of the countries in the regions are EU member states, which places them in a completely different position in comparison to other regional groups. Latin America is bound economically, but not politically or socially, to Northern American economies. Meanwhile, the centres of attraction in Asia are the large countries such as Japan, India and China, with remaining migratory flows directed at the USA, Australia and Europe.

None of these alternatives offers the dynamics implied by EU membership. The Union functions de facto as a single state with no restrictions on movement and settlement, with the inklings of interstate social and health coverage, while targeted investment supports improvements in the quality of life in underdeveloped peripheral regions of the EU.

This plays an important role in migration or repatriation decision making. The ease with which migrants from Eastern Europe can settle in Western Europe, which has up to this point played a negative role for CEA economies, has now turned into an advantage. Returning to Plovdiv from Milan, or to Katowice from Lyon, is a matter of a few hours' travelling and a swift financial transfer.

Freedom and ease of movement, together with the fact that many of the places people are returning to had already started developing strategies to attract human capital, could play a vital role in retaining at least some of this unexpected boon.

There has been a sea-change in migration trends in Europe. After decades of losing population to the West, Eastern Europe suddenly found itself on the receiving end of a large tsunami of people, migrating back to their home countries in the wake of the pandemic.

The combination of a sharp contraction in consumption, widespread business decline, shutdowns of large swathes of the economy, and last but not least, a health crisis, which mandates quick access to health services, has led many migrants to conclude that the safest and most sensible decision would be to return home to their birthplaces. This decision is also underlined by emotional reasons, which cannot be overstated - the need to be with one's relatives, in a place where one has built up a social network that can be a source of mutual support during a crisis.