It’s not the first time that an ‘independent’ report has reflected the ideology and mood music of a government, argues Jenny Bourne, who looks back at key reports from the last fifty years.

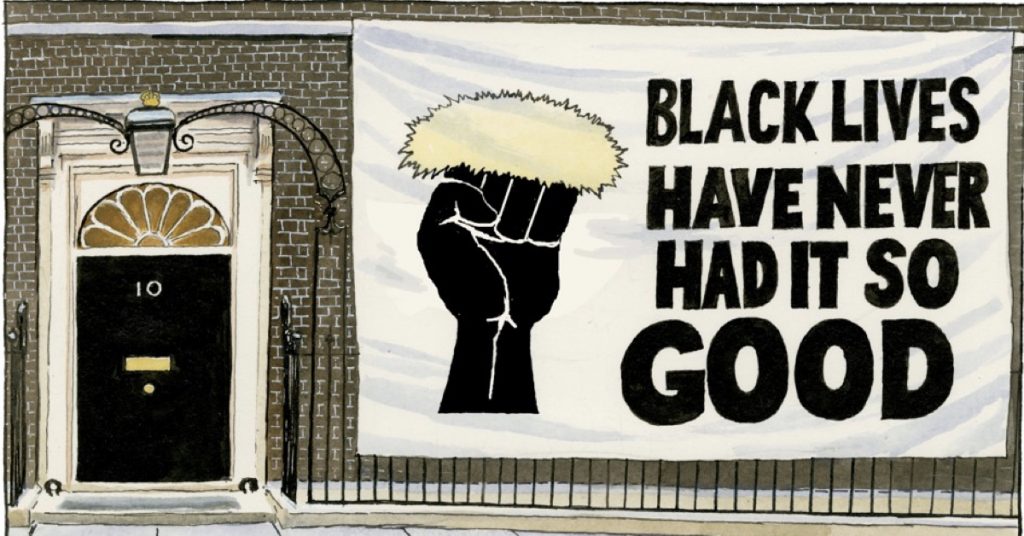

The final word on the government’s Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities (CRED) report has to be Steve Bell’s cartoon on April Fool’s Day – a banner outside No 10, ‘Black Lives have never had it so good’ (a brilliant throwback to Macmillan 1957).

For this is not a serious academic or even empirical overview of racism today, it is more the annual report of the chairman of a corporation writing a load of flannel which bears little resemblance to the annual balance sheet in an attempt to keep the share price up and the investments coming. This analogy is not far-fetched, for everything about this ‘report’ is geared to the market, to success, to competition and individualism. This is the report for neoliberal times.

The garden is rosy. If some can make it, all can make it; negative perceptions of state institutions are based on historical (mis)information; it is rumour rather than reality that gives the police a bad reputation; it is individuals and families who have to take more responsibility; institutional racism is a misused and mis-applied term; there is no generic ethnic minority experience, especially as some groups do better than others – hence one cannot generalise about a society being racist. And we know. For we are ourselves from ethnic minority families. We have had the experience of racism. The bootstraps are all there for the pulling, especially now in the private sector.

Since the report has been well and truly demolished by so many individuals, organisations and angles – academics, ‘race’ bodies, health workers, historians, campaigning groups, unions, even black entrepreneurs and MPs – there is no point reiterating its multiple failings here. But what is important is to understand the ideological stable from which it is coming, and the mood music it tries to orchestrate. Such surveys and commissions are never innocent: they always have some sort of agenda that reflects the colour of the government and the discourses and concerns of the times. It might help to situate CRED by looking back at other key reports and how they reflected and then reinforced the notions of the time. We need the whole context to know how to organise the fight-back.

The Survey of Race Relations 1962-1969

‘We must love one another or die’ – the words of W H Auden frame Colour and Citizenship,[1] the 815-page composite final publication of The Survey by the Institute of Race Relations (IRR). It was the 1958 anti-black riots, the playing of the race card in the 1964 Smethwick by-election and the overtly racist 1968 Kenyan Asian act which drew the attention of the liberal and all-white all-male ‘Lords of Human Kind’[2] that this thing called ‘bad race relations’ might be rearing its head in Britain.[3] Convinced that the time had come to explore ways in which we could progress from a blunt assimilation policy to integration, ‘cultural diversity and equality of opportunity in an atmosphere of mutual tolerance’. Man was rational and, with a little information and education, tolerance would be achieved. The Survey, funded by the Nuffield Foundation, commissioned some 33 pieces of research from academics to ascertain the nature of ‘New Commonwealth’ migration and settlement and then the state of ‘race relations’ across employment, education, health, politics, industrial relations, tolerance and prejudice – (note the media and policing were barely mentioned). The Survey was full of recommendations, smacked of liberal good intentions and seemed geared to influencing parts of the Labour Party and labour movement – though in 1965 and 1968 Labour had chosen to implement racist immigration controls.

By 1969, when the report, based on some five years of research, was finally published, loving one another was beside the point. With black self-organising and Black Power on the one hand and the questioning of ‘bourgeois’ policy-oriented scholarship by radical academics on the other, the report came under immediate fire for its outdated form of liberalism and for appealing to a racist establishment. In fact it was the struggle over research – that it was a racist society, not black people that should be seen as the primary problem – which was to break the old IRR from its governing board, reorientate it and lay the groundwork for the notions of state and institutional racism.[4]

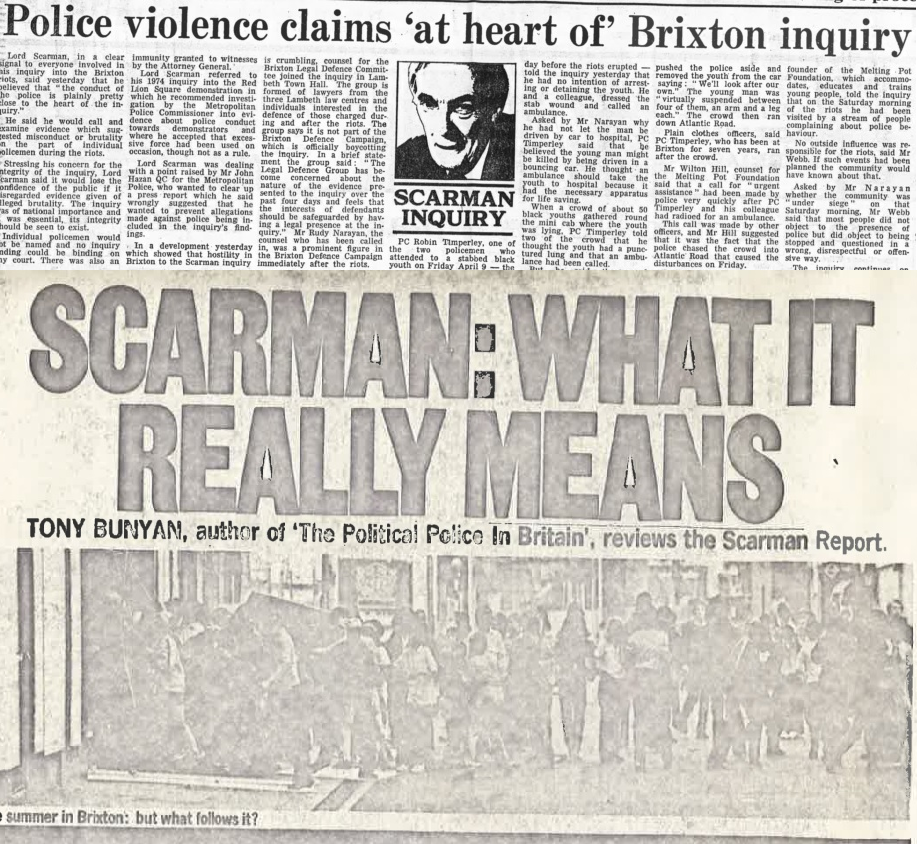

The Scarman Report 1981

It was the Tory government of Thatcher that was forced, by the uncontrollable street ‘riots’ in Brixton for three days from 10–13 April 1981, to find out what had caused the rage of a generation of mainly black young people in the inner-city (which spread to 33 other areas) primarily against the police. Lord Scarman, appointed to head the government inquiry, worked very fast on his brief. By November the Law Lord reported and, significantly, rejected the notion of institutional racism.[5] Instead he found ‘disadvantage’ (how it came about historically, unstated, though the nature of the black family was in part to blame) which was to be remedied by ethnic policies. The police as a force was not racist, though there were a few rotten apples, and a mistrust about the police had grown up through rumour and gossip (presumably not through lived experience of ‘Sus’ stop-and-search etc). But the riots of this generation of young people, if not born here, certainly educated and (un)employed here, shook the establishment which swiftly moved to set up and implement ethnic policies to fund cultural, ethnic and religious groups. Such ethnic politics and policies helped to break down any cross-group unity of ‘blackness’ and through now professionalising ‘community relations’ helped create a small black ‘petit-bourgeoisie’.[6]

The Macpherson Report 1999

The derivation of the Labour government-commissioned Macpherson inquiry into the death of Stephen Lawrence and the failings in the police investigation[7] is key. It emerged of course in relation to the killing of Stephen Lawrence by white racists on an Eltham street – in 1993. But his had not been the only such racist killing. It was the determination of his parents and the campaign that closed around them that forced the government to hold a public inquiry five years after the death. Unlike other inquiries, this one became a public event, capturing both grassroots and media interest. Sir William Macpherson (himself no radical) with his two advisers Richard Stone and Bishop Sentamu, came to a conclusion of institutional racism – and this was a massive step forward.[8] ‘We told Macpherson and Macpherson told the world’ is how one activist saw it. For the first time the black voice about the lived experience of racism and of policing had been heeded. The Macpherson report and its finding of institutional racism were to reverberate not just through policing, but through government departments, public institutions and NGOs. It was the first time that the boot (and all its straps) was on the other foot; the first time that there was no attempt to blame the victim or hand out blame even-handedly.

The back-and front-lash

It was the unequivocal nature of the finding that drew interest from the Tory Right, which had, since the death (at the hands of Thatcher) of the Greater London Council in 1986, been fairly quiet about the iniquities of anti-racism. But Macpherson spurred them on to the offensive. And from the Institute for the Study of Civil Society[9] came a number of publications attacking the notion of institutional and ‘unwitting racism’, exposing anti-racism as a form of Stalinism and revealing the police as now so fearful of public opprobrium that they failed to police black areas effectively, which could have led to the stabbing of Damilola Taylor.[10]

But that was the rump of the old Thatcherite New Right, and meanwhile another anti-anti-racism strain was coming up on the inside track — a small coterie of arrivants, apparently with insider experience of ‘the race sector’ now turning against its principles and publicly denouncing multiculturalism and/or those who overplayed the incidence of racism and the usefulness of the concept ‘institutional racism’.[11] Two key players here were Trevor Phillips (former NUS President, former chair of the Equality and Human Rights Commission who declared ‘we are sleep walking into segregation’[12] and strolled on into the corporate sector and the right-wing influential Policy Exchange[13]), and Munira Mirza (a former member of the Revolutionary Communist Party and Living Marxism supporter, who, as a critic of multiculturalism became cultural adviser to Boris Johnson when London mayor and fundraiser for Policy Exchange). Now as in the US, but on a smaller scale, the Black bourgeoisie has arrived – at least in the political and cultural spheres. And it has a mass media just dying to give it voice and a Conservative Party ready to embrace it.

By and large up to this point, anti-racism narratives had come from a liberal or left position, connecting racism to inequality and injustice and implying a need for social remedy. In that sense the old New Right looked to be died-in-the-wool racists, out of touch and victim-blaming. But in the last ten years there has been a growing persistent more ‘plausible’ right-wing narrative coming from the colour and class that could lend it clout and credence. And it is that change that has been signalled so starkly in the appointment of Mirza as director of the Number 10 Policy Unit[14] and the commissioning in June 2020 of the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities under Dr Tony Sewell (CBE) a teacher with a track record for ‘Generating Genius’ in the black community and a research pedigree on hyper-masculinity leading to black boys’ underachievement.[15]

The report of 2021

The report itself has been, apart from in the Daily Mail and Daily Telegraph, roundly derided – by academics, historians, social commentators, activists, unions, health professionals, even black entrepreneurs and MPs – for its unscientific methodology, lack of credibility, poor argument and lack of transparency with ‘participants’. It has, as we have argued elsewhere, an explicit agenda to downplay evidence of institutional or structural racism and disaggregate both in name and in policy any notion of a cross-minority joint experience of injustice, placing the onus on the individual not the state for positive life chances.[16] The point being made here is that it should not be regarded as serious research but as ideological posture. As Steve Bell notes so cleverly, Black Lives Matter protests may have prompted the Inquiry Commission; but the riposte using a Commission, composed almost entirely of ethnic minority members eminent in a number of fields (including science and business but notably not social research), and flying in the face of the evidence presented of racial injustices in key areas, such as health, policing and education, is that ethnic minorities have never had it so good. This is government sales-talk – never mind the racism, feel the possibilities.

Brilliant article explains where this weird report sits. As a propaganda piece from the Right, it has its own internal logic. Just ignore the evidence submitted by organisations like mine, IDPAD Coalition UK, on recent work Documenting Afriphobia, Structural and Institutional Racism and state that the earth is flat because we say so, there is no Institutional Racism. Ignore the Joint Select Committee Report published in November 2020 as the findings don’t fit the agenda. Fact is the argument about micro aggressions, the lived experience of Racism has gained ground and the CRED report is part of the pushback of the Right. Interesting that one of the key recommendations of the November 2020 report is that since EHRC has not worked with regards to race, a National Race Equality Body needs to be created with local chapters.

I totally agree – I think that Report went so far as to say that the EHRC was “not fit for purpose” and that Black people’s Human Rights were not protected in this country…. That was not a report by an advocacy group or a left wing organisation but by a cross party parliamentary Committee….but we also see how THIS is the thinking influencing policy direction and not the Report from last winter!

As a former colleague of late Sivanandan, we are living in an era of elected democratic authoritarian governance as reflected in the Indian Sub Continent under Modi. And the long term strategic vision of British finance capital embedded with Indian industrial and commercial capital is banking on a post imperial relationship between UK and India. Black Lives Matter movement and the race relations industry need to take cognisance of the role played by Modi and Boris to create confusion between Asian and African/Caribbean communities via publication of the report reviewed. Without a consistent anti imperialist and anti social chauvinist mindset; the accumulation of capital will take precedence over anti racist struggles.