After the success of his 2010 novel How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, Charles Yu turned his attention to Hollywood, working in television for Westworld and Here and Now as a writer and story editor. He is hardly the first novelist to make that move. Faulkner and Fitzgerald did it; Steinbeck and Ray Bradbury too. Recently, Michael Chabon became the showrunner of Star Trek: Picard. Still, in the words of Dennis Lehane, screenwriting and novel writing are “apples and giraffes. Completely different, outside of their core narrative DNA.”

Yu’s new book, Interior Chinatown, seeks to splice the mediums. Nominally, it is a novel, but it borrows the form, style, and argot of a screenplay. In some ways, this makes sense, for it tells the story of a man, Willis Wu, who feels like an extra in “a life at the margin made from bit parts.”

Wu lives in a Chinatown SRO above the Golden Palace restaurant, where a police procedural called Black and White (about two cops, one black, one white) is in perpetual production. “Wherever they go that’s where they’re meant to be,” Yu writes, “the center of things always white and black and black and white.” In the drama, as in life, Wu is merely “Generic Asian Man”—though he dreams of becoming “Kung Fu Guy.”

“In the world of Black and White, everyone starts out as Generic Asian Man,” he explains. “Everyone who looks like you, anyway.” The “you” here is Wu—although that pronoun, which Yu uses throughout, places us in Wu’s position, where we feel the shackles of stereotype and slur, expectation and assimilation, tokenism and typecasting. “You are Asian!” he tells himself—and us by extension. “Your brain forgets sometimes. But then your face reminds you.”

The Hollywood milieu is an elaborate (if a little too on the nose) metaphor, allowing Yu to raise timely questions about the nature of identity, the power of popular culture, the importance of representation, and the dehumanization of racism.

The problem is that, as per Lehane, film and fiction remain distinct. Yu, in wanting to have it both ways, doesn’t quite deliver the pleasures of either, offering neither the sublime language of a novel nor cinema’s visual panoply. Instead we get the utilitarian sentences of a script, framing dialogue that, in satirizing bad TV dialogue, also is bad TV dialogue.

It’s not that such a gambit could never work. James Joyce wrote one chapter of Ulysses entirely in script form. But when you read about Leopold Bloom’s adventures in Nighttown, you’re unlikely to ask, “Why did Joyce call this a novel? It’d be better on the stage.” The same cannot be said for Interior Chinatown—an apple in giraffe fur.

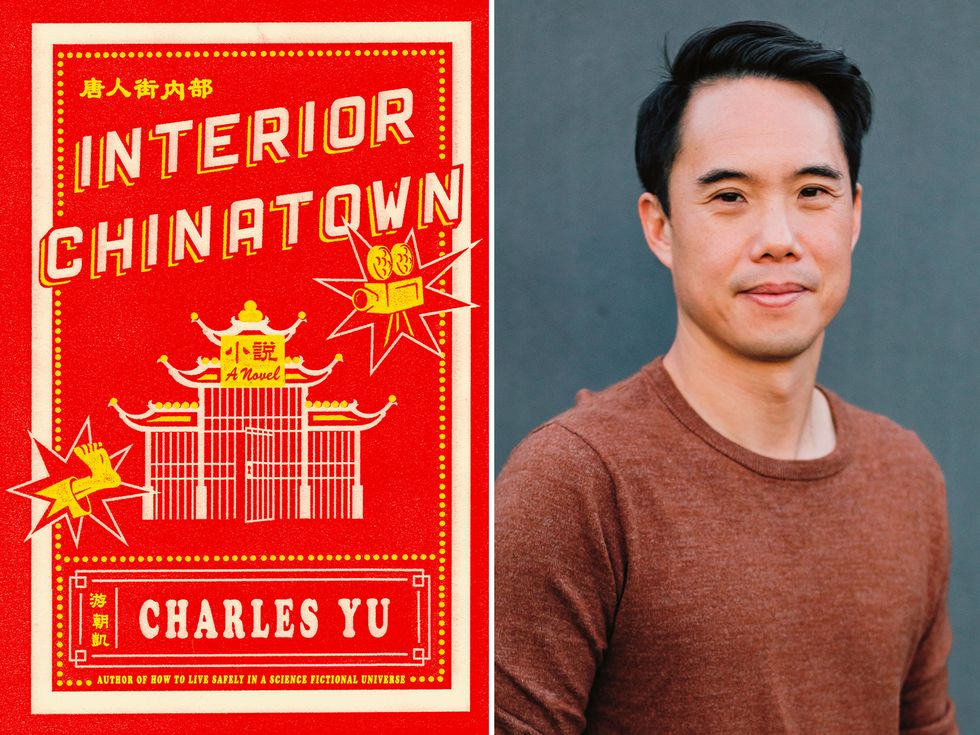

INTERIOR CHINATOWN: A NOVEL

• By Charles Yu

• Pantheon, 288 pages, $25.95