The Checkers Speech After 60 Years

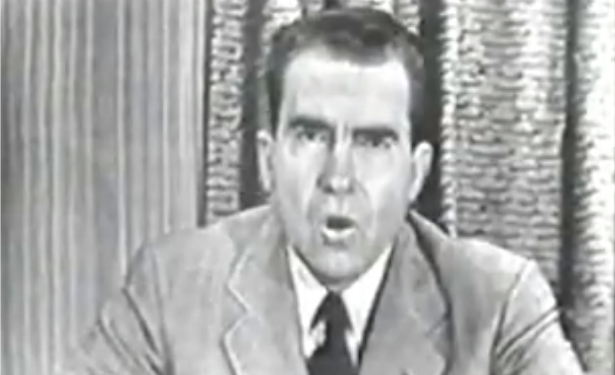

The first-ever nationally televised address both saved and scarred young Richard Nixon, opening a new communications era and upending conventional political imagery.

Sunday marks the 60th anniversary of one of the 20th century's most significant public addresses -- Richard Nixon's much-praised, oft-scorned "Checkers Speech." Delivered by then-Senator Nixon on the evening of September 23, 1952, in a dramatic attempt to answer charges that he abused a political expense fund, the half-hour address was the first American political speech to be televised live for a national audience and was watched or heard by some 60 million people. At stake was Nixon's place as General Dwight Eisenhower's running-mate on the Republican national ticket. The audience was the largest ever assembled.

Viewed through the prism of Nixon's roller-coaster career, the speech resonates today largely because of a single passage: the mention of Nixon's family dog, Checkers. Yet, a 1999 poll of leading communication scholars ranked the address as the sixth most important American speech of the 20th century -- close behind the soaring addresses of Martin Luther King, Jr., John F. Kennedy and Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The "Checkers" speech wins this high rank for one stand-out reason: It marked the beginning of the television age in American politics. It also salvaged Nixon's career, plucking a last-second success from the jaws of abject humiliation, and profoundly shaped Nixon's personal and professional outlook, convincing him that television was a way to do an end-run around the press and the political "establishment."

The "Checkers Speech" foreshadowed the emergence of a new conservative populism in America, emphasizing appeals to social and cultural "identity" rather than economic interests.

Perhaps most interestingly, the address foreshadowed the emergence of a new conservative populism in America, emphasizing appeals to social and cultural "identity" rather than economic interests. The trend would ultimately end the domination of the New Deal Democratic coalition and create a base for Reagan Republicanism and its extended aftermath.

Nixon's began his speech that September evening by explaining the purposes of the fund that some of his supporters had set up after the 1950 election to help their new senator pay for continuing political expenses. The speech went on to emphasize the fund's record of prudent, transparent management. And Nixon ended the address by moving from defense to offense, describing the campaign against him as retribution for his recent effectiveness as an anti-communist crusader, including his role in exposing Alger Hiss as a likely Soviet spy, and delivering a blistering attack on the incumbent Truman administration.

It was, however, the middle passages of the speech, laying out his family's financial circumstances in excruciating -- and what Nixon accurately described as "unprecedented" -- detail that galvanized an instantaneous turnaround in popular opinion. It was the largest such swing ever. The discussion, later described as Nixon's "financial striptease," concluded with words that are still among his best-remembered -- touching a responsive chord among many millions, even as they lay bare his sense of embattled resentment:

That's what we have. And that's what we owe. It isn't very much. But Pat and I have the satisfaction that every dime that we have got is honestly ours.I should say this, that Pat doesn't have a mink coat. But she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat, and I always tell her she would look good in anything.

One other thing I probably should tell you, because if I don't they will probably be saying this about me, too. We did get something, a gift, after the election....

You know what it was? It was a little cocker spaniel dog ... black and white, spotted, and our little girl Tricia, the six year old, named it Checkers. And you know, the kids, like all kids, loved the dog, and I just want to say this, right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we're going to keep it.

When Whittaker Chambers published Witness, the mammoth memoir of his conversion from communism, he concluded by describing the Alger Hiss controversy -- in which he had played the central role as Hiss's accuser in 1948 -- as an epic social conflict. On one side were "the plain men and women of the nation" and on the other "those who affected to act, think and speak for them ... the 'best' people ... the enlightened and the powerful."

In Chambers' view, those who prosecuted Hiss, including Nixon (with his "somewhat martial Quakerism"), came mostly "from the wrong side of the railroad tracks." They were "humble people, strong in common sense, in common goodness, in common forgiveness, because all felt bowed together under the common weight of life."

The division between beleaguered commoners and a privileged elite had long been a familiar theme in American politics, normally used by Democrats to champion the cause of farmers and laborers against business-oriented Republicans. But Chambers' formulation recast the division in social and cultural terms, moving beyond pocketbook controversies to focus on "values," "lifestyles" and so-called "social issues." It heralded an emerging new strain of grassroots conservatism, and Nixon was quick to seize the rhetorical opportunity. Like Chambers, he saw mirrored in his personal struggles the dichotomy between sophisticated privilege and humble endeavor, and drew political and psychological sustenance from the support of what he would come to call "the silent majority."

When Witness was published in May of l952, Nixon reviewed it enthusiastically for The Saturday Review of Literature. The book topped The New York Times best seller list for three months that summer, and, on September 23, its outlook and some of its language made its way into Nixon's television address.

Nixon and his staff would always and only refer to it as "The Fund Speech," resenting the "Checkers" label as one that trivialized his remarks. Yet even supporters who came to consider the speech "an American masterpiece" would observe that it was less about his "Fund" as a symbol of alleged corruption than about "Checkers" as a symbol of middle American values.

Nixon, then 39, prepared the speech during a period he later described as the "hardest," "sharpest" and "most scarring" of his young life. His salvation, as he saw it, would lie with "millions of Americans," gathered around radios and television sets in homes across the land. "God must love the common people; He made so many of them," Chambers wrote in Witness, quoting Lincoln. Nixon's speech would highlight the same quotation.

The lasting accomplishment of the "Checkers" speech was not so much that Nixon explained his "Fund," nor even that he saved his candidacy. In the process of accomplishing those goals, he also took America's conventional political imagery and turned it upside down.

Scripps-Howard columnist Robert Ruark, saw the point immediately. "The sophisticates...sneer," he wrote just after the address, "but this came closer to humanizing the Republican Party than anything that has happened in my memory....Tuesday night the nation saw a little man, squirming his way out of a dilemma, and laying bare his most private hopes, fears, and liabilities. This time the common man was a Republican, for a change....[one who] suddenly placed the burden of old-style Republican aloofness on the Democrats."

If the Fund crisis presented Nixon with an extraordinary ordeal, it also handed him an extraordinary opportunity. New technology gave him the rapt attention of 60 million people; a recent firestorm of media criticism had positioned him as the ultimate underdog in an unprecedented drama. And yet the charges against him were entirely unproven.

Nixon's later, Watergate-logged history, is often read back into the 1952 context -- feeding a casual assumption that the Fund allegations must have had "something" to them. But neither journalistic investigation in that day nor historical research since have substantiated the charges that the money had been secretly gathered, improperly used or had purchased special influence.

In retrospect, some have even suggested that the crisis was somehow "manufactured," so weak was the case against Nixon. For one thing, private funds to cover travel and mailing expenses for elected officials were a common and widely accepted practice. And Nixon had taken pains to immunize his Fund from criticism.

As the Fund's organizer, Dana Smith, a Pasadena lawyer and Nixon's campaign treasurer, told prospective donors a year earlier, the "pool" of contributors would include only people "who have supported Dick from the start," preventing "second guessers" from making "any claim on the senator's interest." Contributions were limited to a maximum of $500, so that no one could think he was "entitled to special favors." The money, finally totaling $18,000, went into a regularly audited, openly-acknowledged trust account.

Rather than exemplifying the emerging, unhealthy influence of money in politics, as historian Roger Morris has suggested, the Nixon fund can plausibly be seen as an early attempt to respond to that problem.

When Nixon was first asked about the Fund on Sunday, September 14, he gave Smith's name and assumed the matter was ended. Nor is it surprising that his aides took the matter too casually at first, especially given their isolation on a campaign train in central California.

The first major Fund stories appeared on Thursday, September 18, and by Friday the candidate was responding to them at each whistle-stop, though initially with an attack on the motives of his critics that may have overshadowed his explanation of the Fund. An independent examination by prestigious legal and accounting firms was also set in motion -- and a list of contributors was prepared for public release.

Three factors allowed the Fund story to get out of control. The first was the inaccuracy of some journalists -- including their misuse of the word "secret." The New York Post headline screamed: "Secret Rich Men's Trust Fund Keeps Nixon in Style Far Beyond his Salary." It launched a tsunami of scandalized coverage.

A second factor in the escalating furor was the aggressiveness of political opponents (especially Democratic Party chairman Stephen Mitchell, who called immediately for Nixon's resignation). But the third and perhaps most important factor was the ambivalent reaction from General Eisenhower and his entourage, themselves traveling on a campaign train in the Midwest.

Press and public antagonism toward Nixon had mounted since his emergence as a national figure (though only a freshman congressman) during the Hiss controversy. The hot rhetoric of his successful 1950 Senate campaign in California against Helen Gahagan Douglas had sharply amplified his partisan image.

His oratorical fervor escalated as he became the GOP vice presidential nominee and party "point man," flaying the Democrats while Eisenhower stayed above the battle. As the contest heated up, he responded to his "hatchet-man" label by shouting: "If the record itself smears, let it smear. If the dry rot of corruption and communism ... can only be chopped out with a hatchet, then let's call for a hatchet."

Frustrated and frightened Democrats, after 20 years of White House control, were more than ready to seize on the Fund charges, given their relative inability to attack the heroic Eisenhower. The result, however, was that they rushed into a trap. As one historian has put it, the Democrats' handling of the Fund crisis was "criminally stupid." Interestingly, the one prominent Democrat who did not join in the frenzy was Adlai Stevenson, partly because his own private expense funds were so similar to Nixon's.

The reaction of Eisenhower's advisors was a puzzle to many. They had, after all, welcomed Nixon to the ticket two months earlier. Nixon had been an early Eisenhower supporter, helping ensure the general's narrow convention victory over Senator Robert Taft, the conservative hero.

Nonetheless, Eisenhower's closest associates were remarkably ready to believe the fund-related rumors. They had not known Nixon well beforehand -- some were put off by his occasional awkwardness in the urbane world of "drinks and jokes." They were mostly non-politicians, unaccustomed to campaign hyperbole and worried, too, that Nixon's anti-communist rhetoric linked him too closely to Senator Joseph McCarthy.

For the Eisenhower crew, moreover, the campaign was a moral crusade against "politics as usual," and stories about the Fund deeply unsettled them. The immediate charges, some warned, could be the tip of a larger iceberg.

When journalists on the Eisenhower train voted (rather unprofessionally) by a count of 40 to 2 for Nixon's removal, and when letters and telegrams began to run 3 to 1 against Nixon, the pressure on the general intensified. It culminated in an anti-Nixon editorial in the influential New York Herald Tribune, a strongly Republican newspaper published by Ike's good friend, Bill Robinson.

Eisenhower, characteristically, refused to be stampeded. But waiting itself exacted a high cost. And Ike's comment that his anti-corruption campaign must be "as clean as a hound's tooth" was widely regarded as a reproach, drowning out the senator's efforts to defend himself.

The hope -- and expectation -- of Eisenhower's advisors was that Nixon would simply withdraw from the ticket. California's arch-conservative senior senator, William Knowland, was asked to stand by as a substitute running mate. And Nixon seriously considered resigning. He would spare himself an enormous agony -- and avoid being remembered as the man who dragged down Eisenhower.

But two considerations argued the other way. First, resigning would give credence to the charges and hand his enemies a victory. The thought of yielding deeply offended him -- and it outraged his wife. Pat Nixon had opposed his accepting the vice presidential nomination, but her fierce sense of pride now came into play. Nixon must not "crawl," she urged in an anguished 2 a.m. conversation after they first learned of the devastating Herald-Tribune editorial.

Meanwhile, there were strong political arguments for hanging tough. While staying in the race meant risking blame for Ike's defeat, leaving the ticket would by no means ensure success; early polls showed the race to be a close contest. Nixon's resignation would offend conservatives and party regulars, and could drive away swing voters. And Nixon would still be the scapegoat.

Nixon decided to fight. He would agree, of course, to do the general's bidding, but he would not "draw up" his own "death warrant."

Remarkably, it was only on the night of Sunday, September 21st, that the two men spoke by phone. Ike, perhaps still half-hoping for Nixon's resignation, avoided words of direct support. He endorsed the idea of a televised effort to explain the Fund, an idea that had been championed and charted from the start by Robert Humphreys, media guru for the Republican National Committee. But Eisenhower refused to commit himself to a quick up or down decision, even after such an appeal.

Nixon reacted angrily. "This thing has got to be decided at the earliest possible time," he lectured the five star general. "...There comes a time in matters like these when you have to shit or get off the pot!"

In his 1961 book Six Crises, Nixon rephrased his retort to read, "You've got to fish or cut bait," but in his l978 memoirs he acknowledged the earthier language. It expressed not only his mounting frustration but also his sense, as he put it to Eisenhower, that "the great trouble here is the indecision."

Eisenhower's stance, on the other hand, clarified Nixon's challenge. As he later remembered: "Now everything was up to me."

But the challenge was daunting. New York Governor Thomas Dewey, instrumental in putting both "Ike and Dick" on the ticket, had warned Nixon that a mildly favorable response to a televised explanation would not be enough -- perhaps a 90 to 10 approval ratio might be required.

It soon became clear, as Humphreys had argued, that neither an interview program nor free time from the networks would do the job. Only by paying $75,000 for a half hour of prime time could Nixon maximize the audience and control the format.

It is remarkable, in retrospect, that so many tactical media decisions were made so well, despite limited time, the absence of precedents, and the enormous pressure. They included: paying for exposure rather than scrounging for free time; avoiding a coveted Monday night spot (after I Love Lucy) because it would allow insufficient time for preparation and for building the audience; selecting a Tuesday spot (following Milton Berle's popular show) rather than a later date which might dissipate the dramatic tension; building suspense by refusing to discuss the speech (not even to disclaim rumors that Nixon would be quitting); eliminating any studio audience (even press and staff watched from another room); and finally, selecting as a stage setting "a GI bedroom den," an intimate middle-American set, including a desk, a bookcase and an armchair for Pat Nixon.

Underlying these decisions was a concept still new to the television era, although it had characterized Franklin Roosevelt's fireside chats on radio. For this speech, the camera would not be a journalistic instrument, looking in upon an event and conveying that story to the public. For the first time, a national television audience would participate directly in a living room to living room encounter.

It would be Nixon, alone, with the people. The reporters and the politicians -- his own staff and Eisenhower's -- would all watch on television. And none of them would know what he was going to say.

Nixon flew to Los Angles from Portland, Oregon, where his train tour had ended, on Monday morning, the day before the address. He isolated himself for the next 30 hours at the Ambassador Hotel, sleeping a mere four hours, and working through a fog of personal despair that was becoming a major concern of his associates.

Working from preliminary notes made on airplane postcards, piecing in new information as it was delivered to him, Nixon sketched out the speech on legal pads, finishing one outline, then starting a new one.

Several rhetorical elements had already been "audience tested" on the campaign trail (Pat's Republican "cloth coat" for example, had first appeared in whistle-stop remarks a week earlier, a veiled reference to the so-called "mink-coat scandals" of the Truman years). And the Checkers passage itself was prompted, as Nixon later acknowledged, by Franklin Roosevelt's effective references to his "little dog Fala."

Nixon decided against using a manuscript -- it would forfeit the "spark of spontaniety" he valued so highly. He intended to prepare a third draft outline, and then, remarkably, to speak from memory.

This plan was upset, however, by a bizarre development. Just as Nixon finished the fifth and final page of his second outline on Tuesday afternoon, Thomas Dewey phoned, relaying Eisenhower's request that Nixon end the speech by submitting his resignation for Eisenhower's consideration.

Devastated by the request, Nixon stood his ground. "Just tell them that I haven't the slightest idea what I am going to do," he responded when Dewey pressed him. "And if they want to find out they'd better listen to the broadcast."

There was no time now for a third outline, no time to memorize, nor even to reconsider his path. Grabbing his five pages of notes, he left for the El Capitan theater twenty minutes away in Hollywood. When Ted Rogers, his television advisor, asked how he would close, Nixon replied, "I don't know..." Three minutes before airtime, he told his wife, "I just don't think I can go through with this." "Of course you can," she responded, taking his hand and leading him to the set.

The last page of his hurriedly scribbled notes read: "The decision must be made by Nat'l Committee. I will abide by their decision. You help them -- let them know either way...." And he stayed with that formulation, though it meant defying Eisenhower's request.

Perhaps because of his uncertainty, he mistimed his closing remarks and never gave an address for the Republican National Committee -- the only group with the legal power to change the party nominees once the convention had ended. At the moment, the error seemed fatal. "I loused it up, and I'm sorry. It was a flop" was the first thing he said after going off the air, throwing his notes to the floor and burying his head in the stage draperies. But even this slip turned to his advantage as supporters, unsure of where to send their responses, sent multiple copies in many directions.

By one count, there were some four million responses to the speech -- virtually all of them pro-Nixon. The National Committee alone reported 300,000 letters and telegrams signed by a million people. The count ran 350 to 1 in Nixon's favor.

The address not only touched a responsive nerve in the body politic, it seemed to open a national tear duct. Nixon's first hint that the speech was not "a flop," he said, came when he noticed tears in the eyes of the cameramen. Eisenhower's wife Mamie wept as the speech ended and even Bill Robinson (who sat with the Eisenhowers in Cleveland) found that his eyes were moist with emotion. In California, the man who removed Nixon's makeup told him, "There's never been a broadcast like it before." Ted Rogers reported that the theater switchboard was lit up "like a Christmas tree." "Thousands were in tears of emotion," wrote the Los Angeles Examiner, describing the effect as a "wildfire." A cowboy in Missoula, Montana, handed a $100 bill to a Nixon associate with the comment, "That's the best speech I ever heard." Back in Cleveland, some 15,000 tearful Republicans chanted "We Want Nixon" as they waited for Eisenhower to greet them.

But Eisenhower, who had watched the speech with cool detachment, remained non-committal. "I shall make up my mind ... as soon as I have had a chance to meet Senator Nixon face-to-face," he concluded, summoning Nixon to meet him the next evening in Wheeling, West Virginia.

When reports of Eisenhower's reaction reached Nixon amid a jubilant celebration back at the Ambassador Hotel, the Californian "blew his stack" as he later put it. "What more can he possibly want from me?" he asked his aide, Murray Chotiner, adding, "I'm not going to crawl on my hands and knees to him." And he dictated a telegram of resignation.

Chotiner tore up the telegram and convinced Nixon to go to Wheeling, provided he could be assured of Eisenhower's support in advance. But this response was interpreted as "insolent" by the General's camp, and for a few hours ragged nerves and wounded pride on both sides threatened to tear the ticket apart again.

In the end, Nixon went to Wheeling, persuaded by his old friend, journalist Bert Andrews, calling from the Eisenhower train. Nixon need not worry about the outcome, said Andrews: "The broadcast decided that. Eisenhower knows it as well as anyone else. But you must remember who he is... He is the boss of this outfit." Meanwhile, Eisenhower, impressed by the swelling public reaction, "shrugged and nodded" his assent to a quiet pre-meeting commitment.

By the time Nixon arrived in Wheeling, Eisenhower was "grinning all over," as he climbed aboard Nixon's plane to announce, "You're my boy." At a stadium rally, he announced the National Committee's 107 to 0 endorsement of his running mate. Nixon told the crowd of the two moments in his life when he was proudest to be an American: the first was looking down from a Manhattan window while Ike rode by in a postwar victory parade; the other had come that very day when he realized that "all you have got to do in this country of ours is just to tell the people the truth."

In fact, the lessons of the fund crisis were far more complex than that -- for Nixon and for America.

To begin with, there were significant political legacies, including a persistent wariness in the Eisenhower-Nixon relationship. The Republican Old Guard, on the other hand, rose even higher in Nixon's affections, including leading supporters such as Robert Taft, Joe McCarthy and Herbert Hoover. And while Nixon was bitter about colleagues who abandoned his cause, he carefully remembered those who stood with him that September, including two whose warm letters of support almost leap from the archival box as one explores the "Fund speech" files at the Nixon Presidential Library. One was from a young Minnesota lawyer named Warren Burger, whom President Nixon would later make Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Another came from a junior Michigan Congressman named Gerald Ford.

Nixon's response to the crisis that Autumn was a series of even rougher assaults on the opposition, rhetoric he would later describe as "unconscious overreacting" to the Fund attacks. But the overreaction would further magnify his partisan image.

Nixon's attitudes to the press also were transformed. He felt profoundly wronged by what he saw as the malevolence or sheer sloppiness of many reporters, and disillusioned by a pattern of journalistic indifference as he tried to get his own story out. Simply telling the truth had not been enough. Only a direct broadcast appeal over the heads of the press and the politicians had saved him.

When he asked his chief media assistant, James Bassett, how the press had reacted to the speech, Bassett would mark a new chapter in the life of the candidate -- and the country -- with his casual response: "It's not important now."

Above all, the Fund speech marked a turning point in the history of political communication. While more people witnessed the speech on radio than on television, it was the still-novel impact of the televised images that would long linger in public memory -- especially among the political classes. In one-half hour, television had become a central instrument of political leverage, and neither the traditional press nor traditional forms of power brokering would recover their previous influence.

When Walter Lippman described the Fund speech as one of the most "demeaning experiences" the country had been through, he was objecting less to Nixon's emotional appeals than to the fact that a leader like Eisenhower had been forced to count telegrams and telephone calls. "Mob rule" Lippmann called it.

With this new medium came new rules, new requirements that Nixon anticipated. Though Pat Nixon was shaken, for example, by the need to reveal personal financial data, her husband reconciled himself to living "in a fishbowl." While his proudly private parents cringed as he told of family struggles, their equally reserved son saw in such details a new way to build public rapport. Candidates' families -- not to mention their pets -- had been only occasionally visible in American politics; Pat Nixon's presence on the "Checkers" set was jarring and inexplicable to many. After "Checkers," families would become central participants in a new political dramaturgy.

Nixon's central challenge was not simply to address the immediate charges against him, but to inoculate himself against future ones. It was not enough to prove himself a non-liability -- he had to become a positive asset. He accomplished this goal by identifying himself not only with the circumstances of "ordinary" Americans, but also with their resentments of the fancy and facile elite. The attacks on him, in this context, became yet another symbol of privileged arrogance. And the apparent normalcy of his life convinced millions that he was truly "one of us."

To be sure, if many wept as this picture unfolded, many others scoffed; and their scorn would become another legacy of the crisis. "The "Checkers speech" would account, in significant measure, for a visceral sense of distaste and distrust among many of Nixon's permanent critics, forever suspicious of what they saw as his "maudlin" or "corny" appeals.

Nixon would later describe the Fund speech, like the Hiss affair, as an immediate triumph which sowed the seeds of future defeats. These important events persuaded his enemies to demonize him.

But the Fund crisis, in particular, was also important because of what it did to Nixon.

On the one hand, it put him into the first rank of American celebrities, a star shining now under its own power and not because of reflected light. And it reinforced his confidence that he could rescue himself from even the most perilous of difficulties by appealing directly, through television, to his silent majority.

The Checkers speech surely qualifies as one of the most successful rhetorical exercises in American history. Yet those six September days left deeper wounds than any of Nixon's political crises prior to Watergate. While he buoyantly created an informal club, "The Order of the Hound's Tooth," for those who had shared the ordeal, this was not a drama he was ever eager to recall. Pat Nixon simply refused ever to talk about the matter. The bitter legacy of the Fund experience would color Nixon's perspectives, and sometimes skew his judgments, for the rest of his career.

It is impossible to read or to watch the Fund speech six decades later without thinking of a later Nixon, and of later crises. But it is worth trying, nonetheless, to return to this speech much as 60 million Americans came to it in September of 1952, knowing very little about Richard Nixon except that he was a very young man with a very big problem, his back against the wall, making a last ditch effort to rescue his already embattled career.