The phrase Jay Inslee used was “permanent emergency.” This was before Lytton — the town that had, days earlier, set Canada’s all-time heat record, drawing waves of “heat tourists” as witnesses to “desert heat” north of 120 degrees in a place where typical June highs were in the mid-70s — burned to the ground just 15 minutes after the arrival of smoke. It was before wildfires raging in British Columbia produced their own pyrocumulus thunderstorms, which produced their own lightning strikes that lit up the landscape again with fire — 3,800 lightning strikes, according to one count, each striking the dry tinder that those in the West now know to call “fuel” and the rest of the world, watching an agonizing drought and heat event unfold, is learning to call just “the West.” A tinderbox half a continent wide.

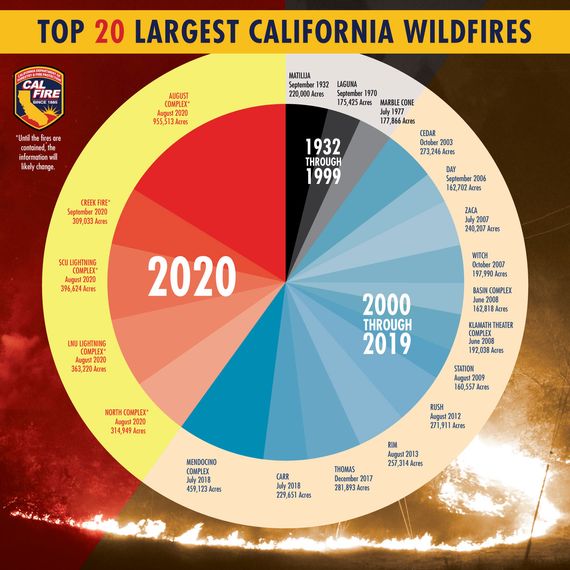

In Portland, Oregon, where temperatures got as high as 116, setting new records three days in a row, with power cables melting in the heat, the smoke plume from Northern California’s Lava fire settled over downtown on Tuesday. If the whole region was enclosed in a “heat dome,” as the meteorologists kept saying, it was beginning to fill with wildfire smoke and not slowly. While the Lava fire had grown to 15,000 acres in its first day, just on the other side of Mount Shasta burned the Tennant fire. What lies ahead is quite likely to be the worst fire season in modern California history, its strongest competition the fires of last year and the ones only two years before that.

In British Columbia, there were at least 486 “sudden deaths” in the midst of the heatwave — a number that is sure to grow many times over, since deaths from heat are rarely so obvious they can be identified in real time rather than statistical analysis. In Portland, at least 63 have died, and in Seattle, where less than half of homes have air conditioning, the extreme heat has put more than a thousand people in the hospital already. Local hoteliers were celebrating, however — their hotels full for the first time since the beginning of the pandemic, with locals fleeing their homes in search of the relief of AC. “It’s been a blessing,” one said.

Elsewhere in Washington State, the roads were melting and agricultural workers as young as 12 and as old as 70 were starting their shifts at 4 a.m. to try to harvest the region’s cherries and blueberries before the fruit was fried by the heat. In Sacramento, residents complaining that the tap water tasted too much like dirt, thanks to the ongoing drought that may be the worst the American West has seen in millennia, were told to “add lemon.” In Santa Barbara, people have been advised to jerry-rig DIY “clean-air rooms” in preparation for the coming fire season, now already in full swing — months ahead of what used to mark the beginning of peak activity in the fall. Suppliers of sparklers were shuttered headed into the Fourth of July weekend. In Alaska, at the edge of the heat dome, the climate writer Eric Holthaus noted, “calving glaciers are producing ‘ice quakes’ as powerful as small earthquakes as they crumble into the sea.” It was hotter in parts of Canada and Oregon, climate scientist Zeke Hausfather pointed out, than it has ever been in the history of Las Vegas, smack in the middle of the Mojave Desert.

“It blows my mind that we could get the temperatures that we’re observing here in the Pacific Northwest, especially on the west sides of the Cascade,” the Washington State climatologist Nick Bond told the Guardian. “I would have been willing to guess something like that in the middle of the century, in the latter part of the century.”

Even in the middle of a permanent climate emergency, this heat wave is an extraordinary event, and yet Bond the specialist is naming the same intuition felt this week by many climate normies who’ve managed somehow to find ways to blink past the spectacular tragedies of the last few years: In certain places and on certain days, at least, even the terrifying distant future is already here. Speaking to Axios, oceans-policy expert Jean Flemma, who lives in Portland, went further. “I fear for the future of humanity.” Casting one’s perspective backward instead is just as disarming and disorienting, since even the most cautious estimates put this heat event as, by historical norms, a once-in-several-centuries phenomenon—once in the course of American history, say, or once since the invention of industrialization. According to one calculation, the heat wave was five standard deviations above expectations, meaning it was an event that should arrive, in the absence of climate change, once every 5,000 years. That’s once since the age of Ancient Egypt.

We are experiencing that five-sigma event this year. In British Columbia, it was as hot as it was in Death Valley, California. They called it Death Valley for a reason.

“I know there have been a lot of warm-up acts and preshows, but it really feels like the climate apocalypse said ‘WELCOME TO THE BIG SHOW’ this week,” the poet Saeed Jones wrote on Twitter. “This moment will be talked about for centuries,” the meteorologist Scott Duncan predicted. But will it?

Prophecies often come true as anticlimaxes, the predictions themselves having set the stage too well — serving to acculturate as well as alarm, introducing first and then effectively normalizing the possibility of events that would have seemed, not so long ago, unthinkable. Climate activists, often privately despondent themselves, have long worried about the costs of alarmism as a rhetorical strategy, warning it would end not in panicked action but fatalism and despair. What worries me more, as an avowed alarmist, is not that dire warnings inspire leaders and potential activists to give up but that, in shifting our expectations, they encourage us to count as successes any merely catastrophic outcomes that fall short of true apocalypse — and make us see what should be freakish showcases of climate horror nevertheless on a continuum with “normal” rather than as signs of profound ecological disjuncture. Adaptability is a virtue, or at least a tool, in a time of cascading environmental change like the one we are stepping into now. It is also a painkiller or a form of climate dementia.

At the moment, the heat dome is triggering much more public alarm than it is complacency — and that is before the death tolls grow higher and before months more of intense fire likely burn through the same region baked by this heat and sucked dry by this drought. But as the climate journalist Kendra Pierre-Louis suggested, in a fit of justified despair, we have been here before — when last year’s fires turned San Francisco orange and produced an eerily biblical darkness at noon; when Australia’s “Black Summer” bushfires burned through 46 million acres and killed more than a billion animals; when deforestation fires tore through the Amazon and briefly inspired international outrage approaching levels reserved for genocide. That’s to name just a few recent local apocalypses and not even mention the many disasters that have not shaken American consciences, like the drought and famine unfolding today in Madagascar, putting 400,000 on the brink of starvation. Just try to watch this video all the way through.

Earlier this month, a heat wave across the Middle East saw five countries hit temperatures above those seen in the western U.S. and Canada. In Pakistan, 20 children in a single classroom collapsed from heat stress and were rushed to the hospital. Already, scientists have discovered that across Pakistan and throughout the Persian Gulf, regions have reached combinations of temperature and humidity that are literally beyond the human threshold of survivability. The term for this measure is “wet-bulb temperature,” and it is sure to become terrifyingly more familiar in the years ahead, just as “red flag warning,” “fire tornado,” and even “carbon dioxide equivalent” and “1.5 degrees Celsius” have in the years just past.

“What kind of awareness quotient are we looking for?” the writer Sarah Miller asked Wednesday, in a brilliant, raw blog post, republished by Nieman Lab, meditating on the limits of climate communication in the face of rolling disaster. “What more about climate change does anyone need to know? What else is there to say?”

She closed her essay this way:

Writing is stupid. I just want to be alive. I want all of us to just be alive. It is hard to accept the way things are, to know that the fight is outside the realm of argument and persuasion and appeals to how much it all hurts. It is terrifying to know that the prize for many who care may be prison or worse. But all the right words about climate have already been deployed. It’s time for different weapons.

Last week, a few months in advance of the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, to be held this fall, a draft of the upcoming IPCC report, which essentially summarizes the state of scientific understanding of climate change for policy-makers, was leaked to the press — presumably as a corrective to a recent wave of positive coverage of net-zero pledges by nations and corporations. It was also a tactical leak, since the report itself won’t be released until long after COP, and one that served as a kind of admonition — that to satisfy the standards of not just the world’s scientists but the planet’s climate itself, everybody is going to have to do much, much better. In general, these reports, which are issued only about once a decade, traffic in the language of scientific caution. This one seems to have been written more like a hostage note.

Agence France-Presse, which received the leak and has since guarded it quite closely, summarized the draft report in three striking paragraphs:

Climate change will fundamentally reshape life on Earth in the coming decades, even if humans can tame planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions.

Species extinction, more widespread disease, unliveable heat, ecosystem collapse, cities menaced by rising seas — these and other devastating climate impacts are accelerating and bound to become painfully obvious before a child born today turns 30.

The choices societies make now will determine whether our species thrives or simply survives as the 21st century unfolds … But dangerous thresholds are closer than once thought, and dire consequences stemming from decades of unbridled carbon pollution are unavoidable in the short term.

This is just the journalistic summary, of course, and journalists are always subject to criticism for hyperbole even when merely restating the findings of the most pedigreed science. Unfortunately, the quoted portions of the leaked report are just as grim as the write-through.

“The worst is yet to come, affecting our children’s and grandchildren’s lives much more than our own,” the report states, according to the AFP. “We need transformational change operating on processes and behaviours at all levels: individual, communities, business, institutions and governments,” it continues. “We must redefine our way of life and consumption.” In an obvious understatement, it notes, “current levels of adaptation will be inadequate.”

The message is literally earth-shaking. At two degrees of warming, the draft suggests, 420 million more people would be exposed to extreme, potentially lethal heat waves, and 410 million more would suffer from water scarcity. By just 2050, tens of millions more would suffer chronic hunger and 130 million more extreme poverty.

And yet beyond the four corners of the climate world, it barely registered a peep, perhaps a sign that, as much as alarmism has achieved in recent years in activating genuine climate action, it has also acquainted us so well with apocalyptic premonitions that new ones glide by and the old ones, when fulfilled, manage to hold attention only briefly before the world snaps back into deadening complacency and a growing tolerance for the pains of warming. “Life on Earth can recover from a drastic climate shift by evolving into new species and creating new ecosystems,” the draft reportedly concludes. “Humans cannot.”

That last part is almost certainly not true, at least within the range of temperatures even climate Cassandras expect this century, though of course there may be surprises in store even if we do radically cut carbon emissions. It is also especially striking as a statement of climate fatalism, given that the upcoming IPCC report is expected to devote considerable attention not just to the science of warming and the project of decarbonization but the urgent need for climate adaptation.

That word, adaptation, has been a dirty one for environmental advocates now for decades — a seeming excuse to delay decarbonization, which has always appeared the more urgent matter (and correctly). But climate action alone is no longer enough — it can’t be enough, even given where we are today. And almost no matter what is done, wildfires in the West are likely to grow sixfold, tens of millions more are likely to die from the air pollution produced from the burning of fossil fuels, and as ecologist Simon Lewis noted in a perceptive essay in the Guardian, headlined “More and More of the World Will Soon Be Too Hot for Humans,” “unlivable temperatures are predicted to last longer and occur over larger areas and in new locations, including parts of Africa and the U.S. south-east, over the decades to come.”

The forecast looks grim, at least setting aside, for a moment, the matter of human response to such changes. And yet, in its way, when contemplating our response to that unforgiving future, livability is too forgiving a standard — too forgiving of us, that is. As the horror those in the West are living through illustrates, the matter of warming cannot be reduced to a fork in the road, with one path leading to apocalypse and the other victory. The possibility of the first has already been likely averted, thanks to recent climate action; the opportunity for the second is obviously long past. We are living already in the muddy thick of climate difficulty, some of us sunk deeper into it than others, but we can’t let ourselves be satisfied for keeping our heads out of the muck. Simply because tens of millions of people in Canada and the U.S. are living through the heat dome, however many thousands die from it, and will survive the fire season to come, however much they choke on its smoke, it would be criminal to look back on what is happening now and will happen in the months ahead and think, “We managed.”

But probably it would be just as criminal to fail to focus on managing climate change in addition to stopping it. Indeed, almost inevitably, the matter of management will likely move more and more center stage, as Lewis suggests in his essay, which name-checks a number of areas of needed investment and planning: early warning systems, dramatically expanded cooling centers, and forecasts featuring wet-bulb temperatures, when it comes to heat waves; rebuilding infrastructure, energy infrastructure particularly, to make it resilient in the face of new climate extremes; retrofitting homes and “future-proofing” agriculture by developing new strains of crops that can thrive, or at least survive, in our brutal new world. He didn’t mention defensive infrastructure, such as sea walls and levees, or large-scale controlled burns of forests in places like the American west, or driving mosquitoes extinct through genetic engineering so they don’t begin spreading tropical diseases like dengue or malaria as far north as Scandanavia in the decades ahead. According to models developed by Portland State’s Vivek Shandas, simply “greening” cities through more grass and green roofs, lighter building colors and more tree canopy, could reduce the on-ground temperature there, in intense heat waves, by as much as 25 degrees, compared to an extreme scenario in which the entire city is simply paved into an asphalt future—though he cautions that these are idealized, extreme models, and that the greening, though it sounds simple, would not be exactly easy to implement, certainly in the absence of regular heat emergencies.

For years now, hyperbolic headliners have used those kinds of disasters of warming to declare that the age of climate change had arrived. This year suggests the possibility of a new arrival — the age of adaptation, or what climate-and-energy researcher Juan Moreno-Cruz yesterday called “climate realism.”

Alarmism, he said, was “useless,” and even efforts to decarbonize have served as a kind of distraction. “Stop dreaming up climate solutions, think of climate managing strategies,” he admonished.

Talking climate solutions has left us unprepared for actual climate change. We keep running models and fighting over which “solution” is the best, but we have done nothing to address the impacts of climate change.

Managing climate change is not as sexy as solving climate change, but it’s what we need. Yes, we need real action to achieve deep decarbonization in our economy. There is no amount of adaptation we can do if we don‘t get emissions under control. But we already baked in so much warming we need to deal with it now. We painted ourselves into this corner, and we need to navigate our way out of it. Dreaming about a future carbon-free system will do nothing for people in India and Pakistan today.

Perhaps the great awakening on warming has already happened — or keeps happening and keeps being forgotten, among other reasons so that we can continue to believe we stand just at the threshold of climate suffering rather than well beyond it. But the great awakening on adaptation probably still lies ahead of us. Or maybe that “permanent emergency” is beginning right now.