Friday Harbor, Washington — On a boat dock over the calm, cobalt waters of Washington State's Salish Sea, Jason Hodin raises a rope that pulls a perforated container the size of a milk carton from its resting place a few feet below the surface.

Peeking inside, the marine biologist confirms a hopeful development: After three weeks submerged in salt water, his little sunflower sea stars, are still alive.

“Amazingly, they’re doing pretty well,” says Hodin, a senior science researcher at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories, a field station situated along a pine-fringed bluff in the San Juan Islands, some 75 miles northwest of Seattle. “This is the first pass of whether or not sea stars born in the lab can actually survive in the wild.”

Sunflower sea stars, the world’s second largest sea star species, can grow to be three feet wide and weigh up to 13 pounds. Adults are multicolored, have up to 24 arms, and more than 15,000 tubular feet that allow them to scoot across the seafloor. Adept and swift predators, sea stars swallow their prey—mainly urchins and bivalves such as mussels—spitting out the shells or other indigestible bits. (See beautiful photos of sea stars.)

But sunflower sea stars are the victim of a massive die-off that began in 2013 and afflicted all 20 known species of sea star (previously called starfish) endemic to North America’s West Coast. Suddenly, sea stars from Alaska to Mexico developed lesions, turning into goo and dying within days.

The sunflower sea star was especially hard hit, with one study showing up to a hundred-percent decline across its nearly 2,000-mile range. The culprit, sea star wasting disease, is little understood—scientists are unsure, for instance, if it’s a contagion activated by warming waters or a syndrome brought about by the stress of those higher temperatures.

To counter this disaster, lead scientist Hodin and his team at Friday Harbor Laboratories began trying to breed the critically endangered sunflower sea star in captivity. The viability of the project rested on Hodin’s sea stars remaining healthy, unlike the numerous other captive sea star populations that had all previously succumbed to wasting disease.

In 2020, despite significant setbacks brought about by the pandemic, they succeeded. The lab bred stars have remained healthy, and by studying the sunflower stars reproductive habits and life cycle, Hodin and his colleagues have been able to break new ground on many issues, including better understanding important developmental milestones.

“We know now how fast sunflower stars grow,” says Hodin. “We can compare the ones that we find in the field to the ones that we've grown, and now we can figure out how old they are. We never knew that before.”

The widespread collapse of sea stars, a top predator and keystone species, has had dire consequences for many of the West Coast’s marine ecosystems. For example, the local extinction of sunflower sea stars, which can live for up to 65 years, has led to an explosion of their primary prey, the Pacific purple sea urchin. On a single reef in Oregon, the population of these animals increased 10,000-fold between 2014 and 2019, to more than 350 million individuals.

In Northern California, purple urchins have devoured at least 200 miles of bull kelp forest, leaving nothing but urchin barrens—seafloors carpeted with the spiky invertebrates. Bull kelp, the dominant kelp species from Northern California to Alaska, is a cousin to giant kelp, the towering, tree-like algae that proliferate further south. (See a graphic detailing the delicate balance between species living in kelp forests.)

Up to 95 percent of Northern California’s bull kelp forests have disappeared, gobbled up by urchins and weakened by stress from warmer waters brought on by climate change. Species that depend on kelp forests, such as red sea urchins and red abalone, both fished commercially, have plummeted in number—causalities of the trophic cascade caused by sea star die-offs.

“It's literally equivalent to if there was a disease that struck every mammal on the West Coast,” Hodin says. “That would be the biggest scientific story of all time, yet this crisis is happening with sea stars, and people just kind of accept this. But to a sea star biologist,” he says, “this just doesn't happen. It’s unprecedented.”

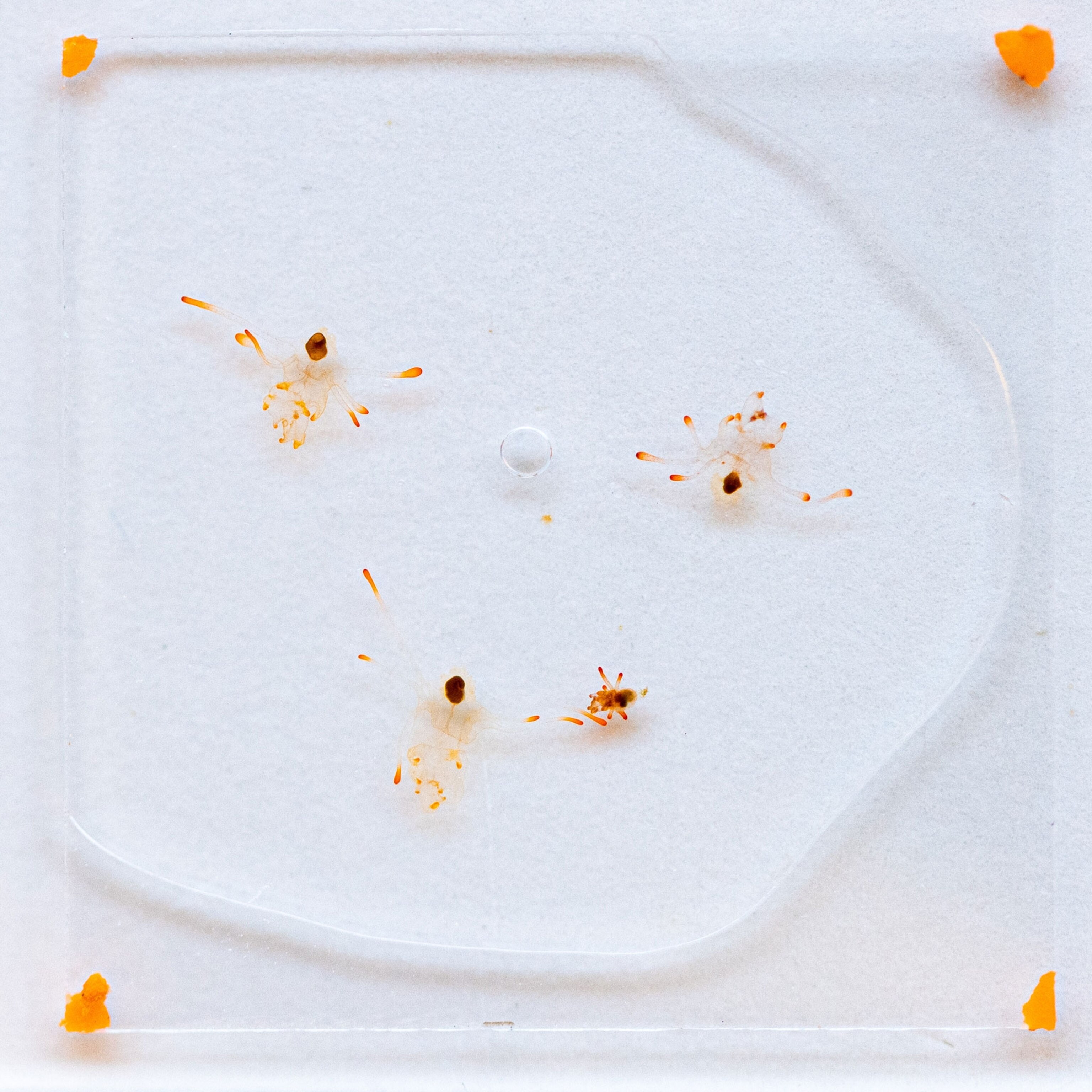

That’s why Hodin spends so much time in the brightly lit lab, surrounded by saltwater tanks filled with light pink, palm-size juvenile sunflower sea stars and their precursors, pinhead-size larvae. Under a microscope, the soft-bodied larvae look more like tiny diaphanous arabesques than sea stars.

Although the wasting disease had decimated sunflower star populations in the San Juan Islands, there was enough of a remnant population for the researchers to collect 30 fully grown stars. They served as the parents for the larvae in the captive-breeding program, which ramped up in 2019, supported by a grant from the Nature Conservancy.

Since then, Hodin and his team have made steady progress raising the mysterious animals. They’ve learned about the sunflower sea star’s breeding and feeding habits, including the fact that small sea stars can be cannibalized by bigger ones, requiring all but the biggest to be segregated by size. The large adult sea stars tend not to be aggressive toward each other, so they can be safely kept in the same tank together.

Ultimately, they hope to build a reservoir of healthy adult sunflower stars that could repopulate areas off the coast and restore badly damaged marine ecosystems.

It’s an urgent mission, Hodin says: Kelp forests, which can be up to 20 times more efficient at sequestering carbon dioxide than land forests, are vital in the fight against rapidly worsening effects of climate change.

The challenge of bringing back sea stars—and kelp forests

Studying sunflower sea star larvae is an important aspect of Friday Harbor Laboratories' research. After the male and female release their gametes, the eggs, fertilized by chance, develop into swimming larvae that disperse in ocean currents, drifting for between two and 10 weeks before settling to the seafloor and growing into juvenile sea stars.

Understanding this complex process could be a boon for the rewilding effort: Dispersing larvae in targeted areas could be a much more practical and economic approach than reintroducing full-grown stars, Hodin says.

Even so, replacing the untold millions of sunflower stars that have died from wasting disease and restoring balance to affected marine ecosystems is a very big challenge.

Meanwhile, California has a five-year plan to restore kelp forests, and nonprofits such as the Nature Conservancy and the California-based Reef Check Foundation are focused on preserving and protecting the few patches of bull kelp that remain as stock from which future kelp forests could grow. These patches of bull kelp tend to be close to shore, where waves keep purple urchins at bay. (Read more about how California’s kelp forests are disappearing in a warming world.)

Jan Freiwald, executive director of Reef Check, employs former commercial abalone fishermen, sidelined because of the collapse of abalone populations, to clear out urchins that border remnant kelp in Northern California’s Mendocino County. In 2020, the fishermen removed more than 25,000 pounds of urchins from the foundation’s 10-acre project site, he says.

“At that site, kelp came back strong this year, and the urchins are not reinvading,” Freiwald says. “It's early on, but so far it's looking really promising.”

The Nature Conservancy has also developed partnerships with private businesses such as Urchinomics, a Norwegian company that collects overgrazing urchins and sells them commercially to restaurants as a luxury seafood dish. Scientists are exploring other uses for culled urchins, such as for fertilizer or chicken feed.

Sea stars are survivors

The biggest challenge in recovering the Pacific ecosystem may well be climate change, which is causing more marine heat waves in the Pacific. For example, an abnormal warming event off the West Coast dubbed the Blob occurred in 2013, around the same time as the sea star die-off.

Initially, scientists thought the Blob activated and supercharged a preexisting sea star virus, which then unleashed the a sea star-specific pathogen, or densovirus. This theory made sense: Even captive sea stars in public aquariums that used piped-in seawater died, a fact that further suggested some kind of contagion in the water itself. (See a striking view of the Blob from space.)

Cornell University microbiologist Ian Hewson, one of the originators of the pathogen theory, has changed his thinking, however. He—along with other scientists—now believes aberrantly warm water episodes, such as the Blob, both reduced oxygen in the seawater and boosted its nutrient content.

With more nutrients came increased bacteria living on the sea stars. These two factors, Hewson says by email, combined to sicken and effectually suffocate the stars, which breathe through gills on their skin.

Not all scientists agree with this theory, and some still think an unidentified pathogen or a combination of factors are at play.

Although Hodin isn’t fully convinced by the latest hypothesis, he acknowledges its appeal. One of the things that’s satisfying about it, he says, “is the fact that they're positing something that is unique to the physiology of sea stars. … So that would explain why it would affect all sea stars and basically nothing else, which is one of the things that we need to explain.”

Overall, Hewson, remains optimistic that sunflower sea stars will persist. “I strongly doubt sea stars will ever go completely extinct,” he says. “Nature has thrown many extreme conditions at them since they arose millions of years ago.”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park