Self-Portrait as an Allegory of Painting, by Elisabetta Sirani, 1658. Wikimedia Commons.

It is hard for us to grasp, from our twenty-first-century perspective, how very young so many of the Renaissance and Baroque artists were when they painted their masterpieces. They were trained from an early age; in an era of great plagues and limited medical knowledge, even if they survived childhood, many of them died in their twenties and thirties. Knowing how fleeting their life might be must have given them a terrible and urgent sense of their own mortality.

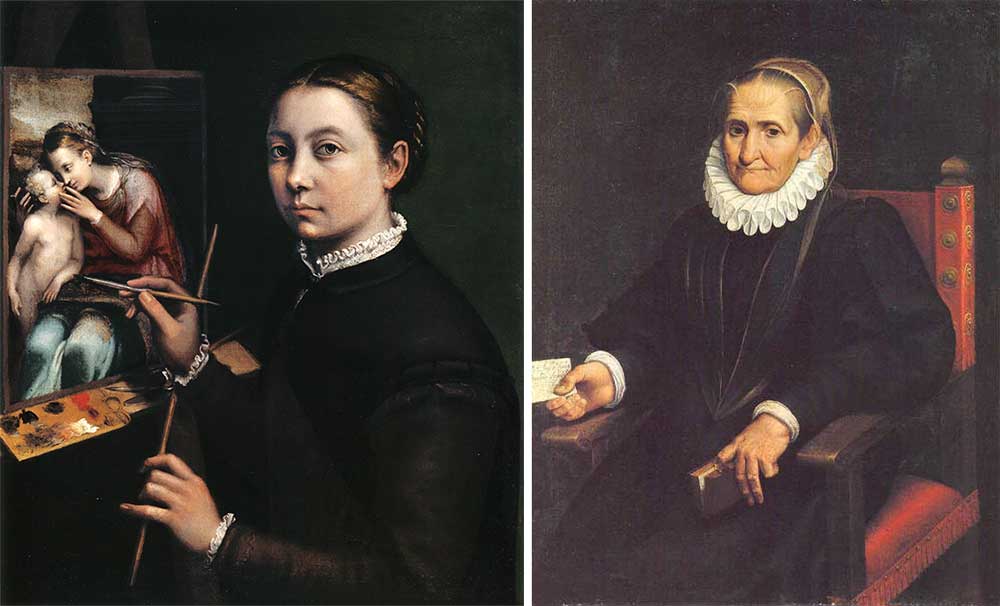

A case in point is the gifted Bolognese artist Elisabetta Sirani, who painted her Self-Portrait as an Allegory of Painting in 1658, when she was only twenty. She pictures herself at the easel, with books and a quill close by, and in the background a small figurine, possibly of Minerva, the patron of the arts. Elisabetta looks effortlessly natural: in a wonderfully bold gesture, a laurel wreath—an ancient symbol of victory—graces her tumbling hair and her clothes are loose, low-cut, and lavish. Perhaps playfully aware of the power of her physical beauty, she looks out at us with the ghost of a smile, her right hand hovering over the canvas, her left holding the partially obscured palette. Our scrutiny of her is obviously an interruption, but she doesn’t seem to mind; she looks vital and at ease, despite the heavy gold chain across her breast. Elisabetta represents herself as both the embodiment of painting and very much herself: full of personality and talent, young and fizzing with life. It’s a defiant statement at a time when to be a woman artist was to be an object of amazement.

Elisabetta’s life was brief: she died suddenly at the age of twenty-seven. But in her short time on earth she achieved an astonishing amount. Her family was artistic: her father, Giovanni Andrea Sirani, had been a pupil of the renowned painter Guido Reni, one of the most important artists of the seventeenth century. Giovanni had no sons and so he taught his daughters; two of Elisabetta’s sisters, Barbara and Anna Maria, were also to become artists. Even as a child, Elisabetta’s talent was recognized. By the age of seventeen she had painted her first altarpiece. When she was nineteen, her father, crippled with rheumatic gout, could no longer paint, and as her mother, too, was bedridden, the young artist became the family’s main breadwinner.

Her energy was limitless. As well as working from dawn to dusk, she also opened a school for women artists, the first in Europe outside a convent. Other women artists had taught female students, but no one had run a school on this scale before. Of her twelve students, Ginevra Cantofoli, Veronica Fontana, and Veronica Franchi were to become professional artists themselves; her sisters Barbara and Anna Maria also joined Elisabetta in the studio and became proficient enough to be commissioned to paint altarpieces. One of the significant, even radical, aspects of Elisabetta’s school is that it took in women who had artistic ambitions but who weren’t from artistic families—a rare opportunity in the seventeenth century. But Elisabetta’s accomplishments didn’t stop with art: she was also a gifted musician and regularly played for gatherings of patrons, friends, and family.

Elisabetta was so prolific that rumors abounded that she could not possibly have been the sole author of her work. To refute her disbelievers, on May 13, 1664, she invited an audience into her studio to watch her work on a painting commissioned by Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici on the subject of Justice, Prudence, and Charity. Elisabetta noted in her inventory that the Grand Duke Cosimo III de’ Medici witnessed her finish the commission in one sitting and was so impressed that he commissioned Elisabetta to paint a Madonna.

Unsurprisingly, the young artist—phenomenally gifted, beautiful, vivacious—became something of a celebrity; she was even the focus of a cult who believed she was the reincarnation of Reni, whose tomb she was to share. Her studio was often filled with visitors; it’s a wonder she found time to paint. Her patrons included, along with Cosimo, such luminaries as his uncle Leopoldo de’ Medici, the Duchess of Braunschweig, the Duke of Mirandola, and papal legates, senators, and cardinals. As an indication of her standing in Bologna, one local businessman, Simone Tassi, bought five paintings by her and the local banker, Andrea Cattalani, owned seven of her works—and Elisabetta was the only female painter whose work he collected. He commissioned her wildly original 1659 interpretation of the story of Timoclea; like Judith and Holofernes (which Elisabetta also painted a version of), it’s a tale of female retribution that was first told in Plutarch’s Lives.

When Alexander the Great’s army invaded Thebes in 335 bc, a captain raped Timoclea, a “matron of high character and repute”; he then asked her if she knew of any hidden money. She led him to a well in her garden and pointed into it. While her assailant was peering into its depths, she pushed him over the low wall, and then, as he lay injured, stoned him to death. This is the moment in the story that Elisabetta chose to tell. As the subject of a painting, it was a bold choice and one that upturned contemporary stereotypes of women, who were considered virtuous but physically weak and intellectually without initiative; men, on the other hand, were, of course, considered powerful and courageous. In most painted versions of the story, Timoclea is pictured at a different moment in the narrative: when the heroine, along with her children, is questioned by Alexander about his captain’s murder and he is so impressed by her that he lets her go free. Until Elisabetta’s painting, Timoclea’s bravery had hardly been represented in Italian art. The young artist depicts her as self-possessed, beautiful, and, despite her grace, strong—strong enough to shove a captain into a well. She is also calm, seemingly unruffled by her violent act. The captain, on the other hand, is pictured in the most humiliating pose imaginable: in the instant before he plunges into the well, he flails about, trying to save himself; he is upside down, his legs askew, his body framed by his red cape, which billows around him like the intimation of blood. His bare legs and arms reveal how young and fit he is, but he’s no match for the dignified Timoclea, who gracefully sends him into the void.

Gaze at Timoclea’s face for a while, and something becomes apparent: she is familiar. As the art historian Babette Bohn has observed, Elisabetta inserted herself into many of her paintings, and this one is no exception. Seen side by side, the protagonist in Elisabetta’s self-portrait and her painting of Timoclea feature the same woman: the small chin, the pale, heart-shaped face, the dark hair and the lively eyes. Elisabetta is Timoclea.

On August 25, 1665, Elisabetta died suddenly with extreme stomach pains—which in recent years has been diagnosed possibly as a chronic ulceration of the stomach and duodenum. Her devastated father accused a servant in her household, Lucia Tolomelli, of poisoning her young mistress. She was put on trial for her murder, but the claims were eventually withdrawn. Rumors of foul play have persisted to this day; even her contemporary the artist Ginevra Cantofoli, who was twenty years older than Elisabetta, was insinuated to have plotted her murder because of a rumored love rivalry.

Elisabetta’s funeral at the Basilica of San Domenico in Bologna was lavish. Despite her family’s humble origins, the city turned out to pay its respects and, as mentioned, she was buried in the same tomb as Guido Reni, beneath a faux-marble Baroque sculpture titled The Temple of Fame that included a statue of the artist painting. “She is mourned by all,” wrote the Gonfalonier of Justice to Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici, “the ladies especially, whose portraits she flattered, cannot hold their peace about it. Indeed, it is a great misfortune to lose such a great artist in so strange a manner.”

Elisabetta’s dazzling achievements have been somewhat overshadowed by the drama surrounding her untimely death. I prefer to think of this brilliant and restless young artist as she portrays herself in her great self-portrait: intensely creative—and totally in charge.

Over the past six centuries, women have had little to gain from advertising themselves as aging, as few patrons would have appreciated being reminded of either their own mortality or anyone else’s—especially that of women, who, going by the paintings that populate most museums, are preferred young and beautiful. As a result, the female self-portrait is often an idealized image; the painter depicts herself as younger, happier, more charming than perhaps she was necessarily feeling at the time. However, there are rare instances of artists defying convention and portraying themselves, with unflinching observation, getting older.

Around 1610 Sofonisba Anguissola painted the first self-portrait of a woman in old age. She is seventy-eight or so; her intelligent dark eyes blaze from her pale, wrinkled face; her thin lips are pursed, possibly due to her lack of teeth; her gray, thinning hair is held neatly beneath a veil. Her worn hands are stark against the stern black of her dress; in her right hand she holds a message to King Philip III of Spain, whose father had welcomed her into court when she was young. It reads “To his Catholic Majesty, I kiss your hand, Anguissola.” Historian Frances Borzello suggests that “unable to journey from Italy to pay her respects in person, she paid them in paint.”

One hundred and twenty years after Sofonisba’s self-portrait as an older woman, Rosalba Carriera depicted herself not only as someone who has aged but as the embodiment of the passing of the seasons, as if she were not only a woman but a landscape as well. In her c. 1730 pastel Self-Portrait as “Winter”, which she made in her late fifties, her gray hair is echoed by the pale fur at her collar: hers is a fearless scrutiny of the aging process. She is a landscape both frozen and yet full of feeling. Her gaze is blunt and direct; although she was to live for another twenty-five years or so, as if sensing her mortality, she pictures herself as the embodiment of the coldest season, a time when the earth might be hard and unyielding—dormant, but still very much alive.

Rosalba was born in 1673 in Venice to a family of modest means; her father was a clerk and her mother a lace-maker. She was a rare exception to the rule that most pre-nineteenth-century nonaristocratic women artists were the daughters of artists. From an early age she helped her mother in her trade; perhaps it was the delicacy of the material she handled day in and day out that led to her interest in miniatures. Although she was possibly trained by the painter Giuseppe Diamantini, Rosalba was in the main self-taught. She was, however, all too aware of what she was up against. “What gives men the advantage over us,” she wrote, “is their education, the freedom to converse, and the variety of their affairs and acquaintances.”

She began her career by painting tiny portraits on the lids of snuffboxes—she was the first artist to paint on ivory, as opposed to vellum. Rosalba was soon in high demand and was commissioned to paint portraits of aristocrats and the nobility, including Maximilian II of Bavaria and the twelve most beautiful women of the Venetian court. She was elected to Rome’s Accademia di San Luca in 1704, painted portraits of Louis XV as a boy and the renowned artist Antoine Watteau, and was admitted to the French Académie Royale.

Frederick-Augustus II, elector of Saxony, filled a room in his palace with a hundred of her pastels, a medium in which she excelled and which she helped transform into a respected and highly collectable art form; she was also an influential teacher and mentor to young women artists. In Austria, Rosalba was championed by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, who bought more than 150 of her works; she also taught the empress painting. In 1713 she painted the portrait of Augustus III of Poland; she instructed his wife, too. The king was to become her most enthusiastic patron (and he certainly had competition): he too bought more than 150 of her pictures. But as is clear in her Self-Portrait as “Winter”, although she often flattered the subjects of her commissioned portraits, when she rendered her own features, she was brutally honest.

From The Mirror and the Palette: Rebellion, Revolution, and Resilience: Five Hundred Years of Women’s Self Portraits by Jennifer Higgie, published by Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2021 by Jennifer Higgie. All rights reserved.