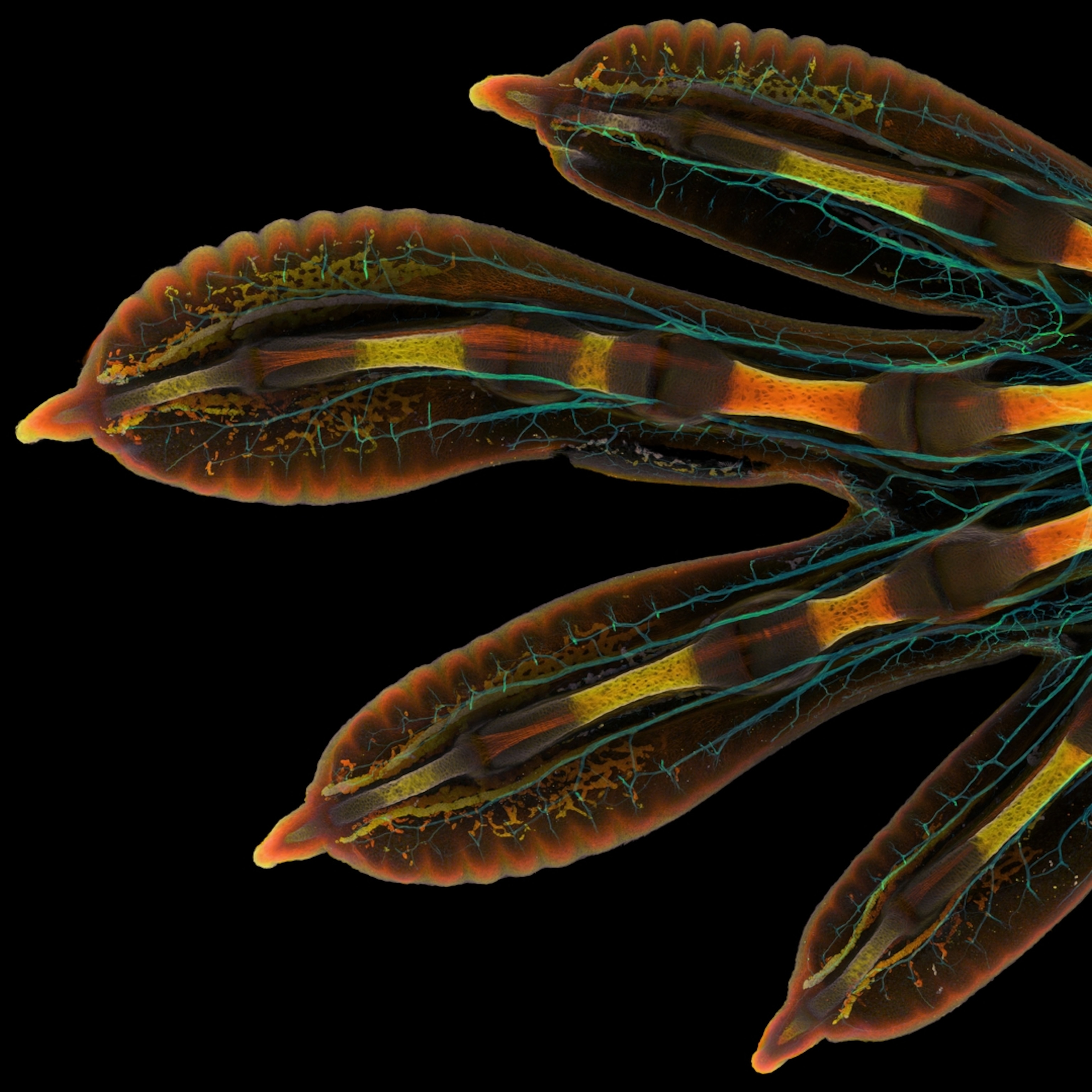

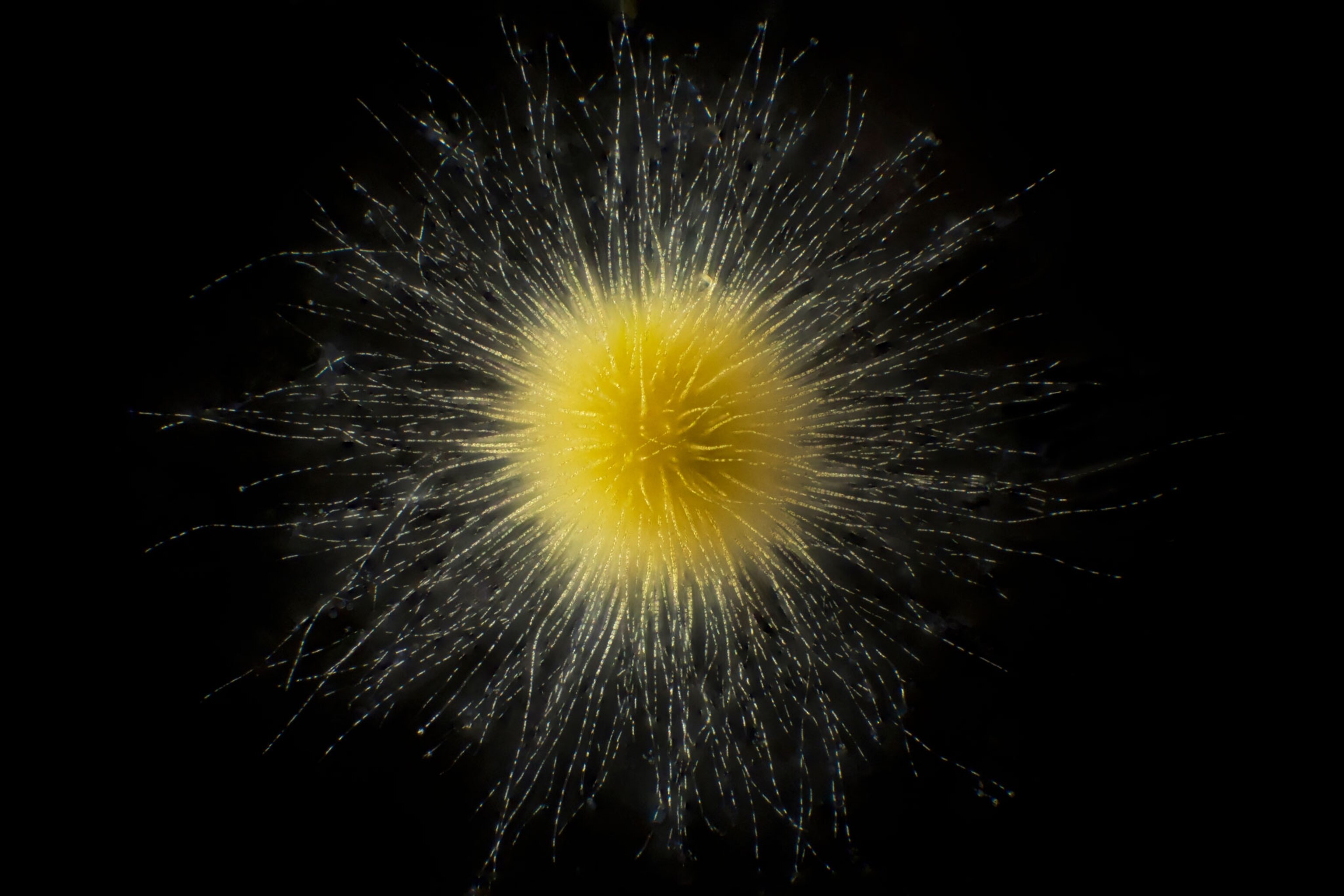

Scoop up a cup of water anywhere on Earth, and you will find strange, entrancing life-forms called plankton. From brilliantly colored blobs to miniature monsters adorned with tentacles and gigantic eyes, every drop of H2O, be it freshwater or seawater, hums with microscopic life most of us have never seen.

For the past three years, Dutch filmmaker and photographer Jan Van IJken has made it his goal to illuminate the beauty of this unseen world. Van IJken has traveled throughout the Netherlands, swishing his plankton-collecting net through various bodies of water and then using time-lapse photography or video to capture the tiny treasures on microscope slides.

“Plankton is so incredibly diverse and incredibly abundant,” says Van IJken, who released a new artistic film called Planktonium on November 17. “Every time I throw my net, I can work for weeks on what I find.”

All plankton can be separated into two basic categories—phytoplankton, which are plants, and zooplankton, tiny animals such as rotifers, which look like they have mini wheels for mouths. (Watch the full-length version of Planktonium.)

Technically, any animal that is free-floating—and therefore can’t control its own trajectory—is considered plankton, which translates to “drifter” or “wanderer” in ancient Greek. That means plankton can be as small as a single-celled organism the size of a white blood cell or as big as a lion’s mane jellyfish, which can reach 120 feet in length.

There’s a reason why plankton need some good PR: They’re crucial to the health of our ecosystems, experts say. (See more incredible photos of plankton.)

Via photosynthesis, plankton churn out as much oxygen as all the plants on Earth combined. “About 50 percent of the oxygen we breathe is produced by phytoplankton,” says Marianne Wootton, senior plankton analyst at the Marine Biological Association in the United Kingdom. “So, every other breath is a plankton breath.”

On the flip side, phytoplankton consume carbon dioxide, acting as an important sink for the greenhouse gas most responsible for climate change, says Wootton.

“They really are the hidden heroes, not just in the ocean, but to the planet,” says Wootton.

Plankton from the bottom up

Plankton are also the foundation of the ocean food chain, particularly as prey for marine mammals such as whales—some of which, like the blue whale, can eat 16 tons of the stuff daily. Take any marine animal—say, sea otters—and plankton are undoubtedly involved.

Not only do otters love to eat mussels, which eat plankton, mussels are also considered plankton themselves during the early part of their life cycle. “So without plankton, there would be no sea otters. Simple as that,” Wootton says.

By the same token, seafood lovers have good reason to pay attention to plankton, says Kelly Robinson, a biological oceanographer at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. (Explore the marine food chain.)

“Everyone loves tuna and crab,” says Robinson. “Well, when they’re babies, they belong to this microscopic group called plankton.”

“We need to understand how plankton function so that we can keep having all the things that we enjoy catching and eating,” she says. To that end, Robinson is studying how both long- and short-term climate changes, such as El Niño-like events, are linked to plankton blooms, which in turn affect jellyfish populations.

Becoming a plankton evangelist

Because plankton remind Van IJken of alien-like creatures, he shot his film as a sort of space odyssey, with a series of otherworldly images moving against a black background.

Van IJken also admits that he approached the film purely as an artist, but that along the way he’s become a bit of a plankton evangelist.

“When I go out with my nets, people see me, and they always ask, What are you doing?” he says. “And I say, I’m making a film about plankton. And then they say, Plankton? What’s plankton?”

Of course, Van IJken is more than happy to explain.

“That’s pretty special”

As critical as plankton are to the planet, even plankton experts don’t usually get to see them in the detail presented in Van IJken’s film. That’s because most scientists fix and preserve their samples, which requires killing them.

At one point in the film, a water flea can be seen giving birth to a litter of fully formed, translucent young. (Read about the spiny water flea, an invasive species in the Great Lakes.)

“Oh, wow,” Wootton exclaimed while screening the film during a Zoom interview. “We do get those guys in our live samples, but I’ve never seen one give birth. That’s pretty special.”

Robinson noted she would have liked the film to include species identifications or more context to explain what the viewer is seeing. But she called the film “beautifully done,” adding that she may use Planktonium in her teaching.

Wootton agrees the film could also inspire the next generation of plankton scientists.

“It’s important to engage people,” she says. “The plankton world is a beautiful world. It's mesmerizing. It's strange. And most of it, we still don't understand.”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

Science

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

Travel

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park