He strides into my art studio with a vitality and energy you can’t fake—the métier of the young. No paunch, no white hair at the temples, no slump in his shoulders, no half-hearted efforts at a flirtation he already knows is marked for failure. All the artists in the neighborhood have flung open the doors to their homes, their sheds, their cramped makeshift studios, their lush gardens, and people meander into these spaces to look at art. Often, they pretend they’re going to buy something—to be polite—but most of the time, they’re simply seeking the pleasure of looking, of taking something with their eyes they don’t have to pay for or give back.

Standing before one of my installations: a young man, nodding. Not only young, but gorgeous. Jet-black hair, eyes shielded by sunglasses, each lens an iridescent swirl of oil rainbow, skin darkened like summer velvet. He’s the spitting image of my husband, down to the constellation of black moles on his neck—but 30 years younger. His arms are sleeved in a sky-blue sweater. My heart catches, a strange kind of ecstasy, and I immediately want to introduce myself, to slowly, carefully roll up the sleeves of his sweater, to run the tips of my fingers along the warm surface of his arms and find his familiar tattoos. He might be my husband, my family. Not just a simulacrum, but the real thing, the human I’ve lost, somewhere in the present.

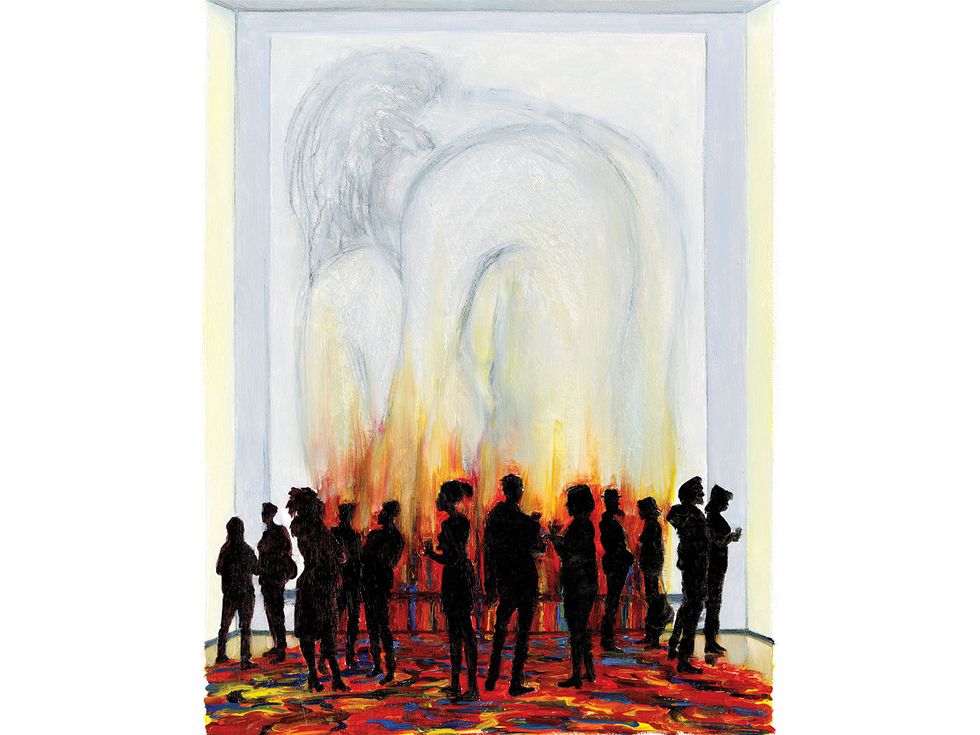

My husband has decided not to come, as per usual, and has fled to the gallery he owns in the city. He hasn’t visited any of the artists participating in Open Studios in years. He’s lost interest in art, he says, even though it puts food on our table. What’s the point? Nobody’s genuinely moved by it. People are faking it, people are desperate to seem sophisticated, he says as he drinks himself into an absinthe-flavored stupor; there’s no reason to hold back, as there are several more bottles of absinthe in the garage, a thank-you gift from a celebrated artist who sculpts phalluses in varying postures and places waxed mustaches on them.

My husband’s in a midlife crisis, but unwilling to admit it, even as all the rituals of crisis come into play. He likes to fill the bird feeder in the backyard lemon tree and watch the hummingbirds flap around it, their elusive wings holograms. He likes to take his time eating, chewing every bite of his cereal slowly, methodically, feeling the easy give of grains under milk. He goes on long strolls for the sole purpose of counting the ramshackle nests of crows, in order to estimate the growth of the crow population in our neighborhood, and he announces, upon every return, that the crows are taking over. He’s interested only in the minutiae of mortality, and it’s taken a grievous toll on our marriage, which has been constructed on an edifice of art, on the edifice of art as a real agent of change in our world. Our relationship’s built not on art, but on a shiftless artifice, I realize now, with dismay.

It’s scorching. Artists offer Dixie cups of lemonade or wine, and most people choose wine no matter how thirsty they are, or perhaps because of how thirsty they are. Milling around my husband’s double are people of every persuasion: in hoodies, in T-shirts, in designer business suits, in leather pants, wearing hoop earrings and red lipstick, waists cinched in corsets, flowy gauze skirts, flaunting piercings like shooting stars all over their bodies. They enter the shed in our backyard, following gold balloons and pasteboard and marker signs. Back in the day, my husband would have enjoyed the people-watching, if nothing else.

I wanted to blow off this yearly ritual too, close my doors. I’m too far along in my career to care much about opening my studio to the public. Long ago, I thought something life-changing might occur at an open studio, that a stranger might walk in and change my life, and the anticipation of the unknown fueled me through the small talk, made me ever more aggressively entertaining. Now I know nothing changes only because you let people look at your work; everything is the same afterward, at least for you, even if you’re hoping your work moves strangers, changes them in some way they cannot immediately articulate. My paintings have grown tame, tame enough to sell, tame enough for living rooms in the heartland even, but I never managed to beckon fame or a legacy, and I understand now, I never will. Yet, force of habit compels me to participate in this pointless ritual, even if I need to do it alone.

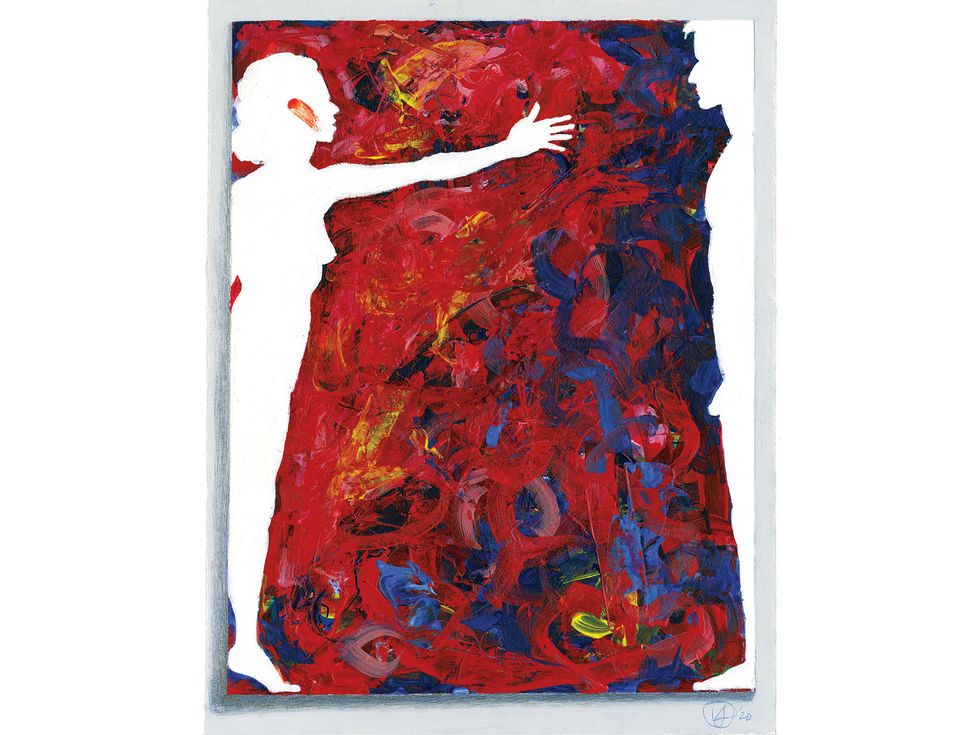

Before throwing open the shed doors around noon, I’d guzzled espresso and painted for hours. I’d stretched two linen canvases and primed them, covering my fingers and hands and overalls with gesso. I’d swirled alizarin crimson into ultramarine. I’d flung blue oil paint onto a canvas entitled Moon, Womb that I’d painted last week, the image of a titanium-white and quinacridone-magenta moon with the shadow of an embryo cast against it. My husband’s double is ignoring the paintings, as he should, since they’re shit. He gazes at an older installation I’ve left on the wall as a kind of litmus test for how easily a viewer succumbs to shock: a wall of unwrapped tampons, hot-glued together, each string casting a skinny shadow, the wall meant to show how the body’s most visceral needs, its deepest reality, serve as a barricade against all else. Next to the tampon installation, from the same period: a wall of birth control dispensers, each painted in streaks of carmine and purple lake, luminous seed pearls nestled inside, in place of pills. My husband loved these installations once upon a time, but now he thinks they’re garish and vulgar. Too needy and erotic and attention-seeking to say anything meaningful, he’s said.

I study my husband’s double from across the room. I want to find out if, in fact, my husband has traveled across time to find me, perhaps to tell me something important I should know about our marriage, perhaps to reveal what I don’t already know about the past that led me to this lonely, barren moment, perhaps to warn me about the future. What if my husband has found a way to break the space and time between us? I would know it was him, I think, if the double has the same voice as my husband. I just need him to speak. How else would we know our time travelers if we run into them, except by the way they appear, except by the way they move around a room. We might be the only ones to recognize them, the only ones to understand that time has been breached.

My husband was once beautiful, and here he is in this young man. Perhaps the sunglasses are an affectation, a way to cloak intense vulnerability. They had been with my husband when I met him. I think about sliding the sunglasses to his brows, slowly, gazing into the seductive brown eyes I already know, carefully removing the sunglasses from his face, running my hands along his cheekbones.

But the young man won’t look at me, not at first. He’s resolutely closed off, even after he abandons the wall of tampons and starts to peer at the paintings with his hands stuffed in his corduroy pockets and an impenetrable air, occasionally nodding or grunting at the art, whether in affirmation or as unspoken criticism, I can’t say.

Other visitors swarm around him, but he stays laser-focused, like he’s truly come to view art, and not necessarily for the free wine and brie and crackers I’ve set out, or even to mingle with other visitors or pick someone up. I breathe in deeply and cross my arms, almost to protect myself from this younger version of my husband, the sense of lost magic that floods me as I look at his countenance. Can I help you?

He glances at me and pauses. You the artist? he asks, as if he already knows the answer.

It’s my husband’s voice. Same intonations, same elegant accent, same eliding of the r.

Yes. I nod uncertainly.

When I was browsing online, yours was the studio I most wanted to see, he says. He holds out his hand, and I shake it with some reluctance. So he doesn’t recognize me, except as the artist.

Your work! It’s phenomenal. I love what you’re doing with even the most mundane objects, the most mundane experiences. Menstruation. Birth control. I love it.

He keeps holding my hand. If he isn’t my husband at a younger age, he should have released my hand immediately. And there’s the pleasant nature, too, of his grip. The peculiar way his hand is precisely the right temperature, no sweatiness, no clamminess, the feeling of it against mine, like we have known each other, intimately, for years. I don’t want to let go either. The room full of strangers spins around us, and I think again of rolling his sleeves up, taking off his sunglasses, but he releases me, finally, and I suck in air.

You OK? he asks.

You remind me of someone, I say. And when he looks at me with an utterly blank face, I want to shake him. How could he not know? It’s maddening. It must be a hoax. I rack my brain to consider who might be trying to play this joke on me. Who have I pissed off in the art world—I shuffle through names.

Still, he says nothing. But he does take off his sunglasses and put them in his pocket. Who? he asks.

Helter-skelter flecks of bronze in his eyes, identical to my husband’s, but there is no recognition there. I scrutinize his jaw, his cheekbones, maybe too closely, hoping, I don’t know for what. Silence consumes us both. He looks at me like he thinks I’m flirting with him, and maybe I am, because I am, in my own mind at least, flirting with someone I’ve known for 30 years.

He touches my cheek. Electricity, startling, overwhelming, painful, passes through my skin, conducted through the water in my body, reverberating like waves in a pond after a stone’s been skipped.

You have some kind of, I don’t know, orangish streak there. Were you painting this morning?

I nod. He takes his hand away.

Can I see the work?

The crowd moves around us, skirts us, and as soon as he asks me to see the work, the sound switches back on, and I understand we aren’t alone, we’re surrounded here in this room by many other people, all of whom I’m supposed to be courting. I realize I’ve inched toward him in my effort to properly see his face, and am now standing far too close to him. Our faces are inches from each other. His pores are identical to my husband’s, but I’m not sure whether pores can be different. I don’t know if he comes closer to me or I come closer to him, or perhaps it’s just natural, when we’re standing in the midst of so much noise and commotion, but close like this, I observe the crooked bump on the bridge of his nose, and the way his upper lip curls ever so slightly with contempt. I know that contempt, the contempt of the young.

I take him to see the new canvases, which I’ve left leaning up against the shed outside to fully dry. He paces in front of them, cagey.

They’re…different, he says finally. Different than what you’ve got hanging inside. Your embryo fixation is interesting.

Fixation? I ask, tension in my shoulders. I’ve been hoping he’ll say he likes these, that he understands what I’m going for, that he understands me. This is what I want most of all: for him to understand me, the way I’m always hoping my husband will understand me, even though my husband never has, and probably this guy, his double, never will either.

Maybe that’s too strong a word—fascination? Isn’t that a kind of hat? No, that’s a fascinator. He smiles a little now, quizzically, like he’s not sure what he’s done wrong, but knows that there must be something.

My eyes might give me away. He steps back, hesitation animating him, and he begins edging away from me. It’s all I can do not to grab him by the arms and pull him back toward me as if we were still in college at a party. We met, drunk off our asses, in the co-ops at Cal. He’d liked my art, and because he’d liked my art so much, he’d invited me to eat cheese flautas like the ones his abuela used to make, and drink icy margaritas, and this was how we’d ended up in bed together that sultry midsummer night, and why we’d moved into an apartment off campus together the following year. Never again had it been the way it was that first year, either the first year when we fell in love, or the first year when we got married, trying to halt our inexorable slide away from each other. We didn’t know then that marriage is a way to be sure you never know someone as he is by himself, not entirely.

Do you have children? he asks. His eyebrows draw together, making a tent squiggle in the center of his forehead.

No, I can’t have children.

I regret immediately saying too much. I’m always saying too much, letting spill details about my life, like I can’t bear to keep anything to myself, like I need the comfort of other people knowing what’s inside my mind, like I need to express myself at the cost of social order, and that’s, I’ve found, a high cost to pay. What does my fertility have to do with him? Nothing, nothing, of course, nothing.

I’m so sorry, he says, aghast, and steps back, and again I want to pull him closer.

It’s OK. I’m past that stage of life.

I say it flatly with no emotion. Sometimes it still hits me with a painful force. Children will never happen for me, not if my life continues the way it’s been going, and not if I keep getting older, if my body keeps aging against my will.

My wife and I are thinking of having kids, he says after a moment, his voice calm anew. I glance at his finger, and see, sure enough, a plain platinum band circles it, the same band my husband has.

You look like my husband, I say in a broken voice. Last-ditch effort because my longing has become unbearable, a kind of excruciating stretching and breaking inside me as I remember the person I was when my husband and I first met, and how much I long to be that person again, instead of this other person, less accomplished for her age, but with more silver hairs, and yet somehow hungrier, ravenous, in spite of being older.

He looks at me more closely, without alarm this time, his eyes wandering my face. He’s noticing me, finally. I hadn’t realized he wasn’t looking at me closely before, and it’s only the contrast of before and now that makes me understand that I’ve mistaken interest in my work for interest in myself. Maybe, in fact, he’s here only because of my canvases, and not to sweep me back in time after all.

What other studios are you planning to visit today? I ask politely, a last face-saving question. Disappointment and humiliation have assumed control of my body, rendered it merely a blushing host, triggering in me helplessness, hopelessness, fragility. Visitors begin to leave the studio, slipping out one by one, and two by two, and I should get back inside, I should play hostess.

He shrugs, and glances down, embarrassed. I was interested in your work, in the materiality of your brushstrokes. No other artists in the catalog caught my attention. When are you finished here?

My eyes meet his. Again, bronze flecks. My husband liked my brushstrokes too, their juicy thickness. I glance at my watch. I’ll be closing up in about a half hour, I say.

Do you need to get back inside? he asks. He looks like he wants me to say no.

I nod, startled that, after all, it’s not just me. Maybe there’s something hanging in the air between us, a curtain to be drawn away.

I’m going to grab something to eat for lunch, he says, but I can come back. He pauses, before asking, Want something?

No, that’s OK, I say. The trays of cheese and water crackers might still be overflowing after everyone leaves.

And he touches my forearm, lingers there a moment. Again electricity, the jolt of that, him and me sharing the same space. But the moment passes, and he walks away, and he doesn’t look back.

I hurry back inside and mingle with the stragglers. They ask me questions about what medium various works are in, how long it took me to install those tampons on the wall, how long it took me to install the birth control dispensers, what glue I used. They don’t ask me as much about meaning, about what anything means, about how my life informs the work. They aren’t interested in the meaning, I realize, for the first time in my career. More, how it makes them feel. My intentions are irrelevant to the art’s reception, and maybe my husband is right to take such intense interest in the hummingbirds, in the speed of their metallic wings, in their zealous emptying of the bird feeder, in the crows invading our neighborhood. Maybe that’s all there is in this life.

Visitors leak out of the studio, having bought nothing. I’m deflated. My work, which seemed so vital, so charged, in the morning, is leached now of all excitement, of all the blood and sweat with which I made it. Merely paint on cloth. Nothing.

I begin to clean up, throwing wine bottles in the recycling and sweeping up crumbs. The brie and crackers are gone, though voluptuous curls of cheese remain on the edges of white plastic knives, and I regret not taking the young man up on his offer of food. I adjust paintings on the wall.

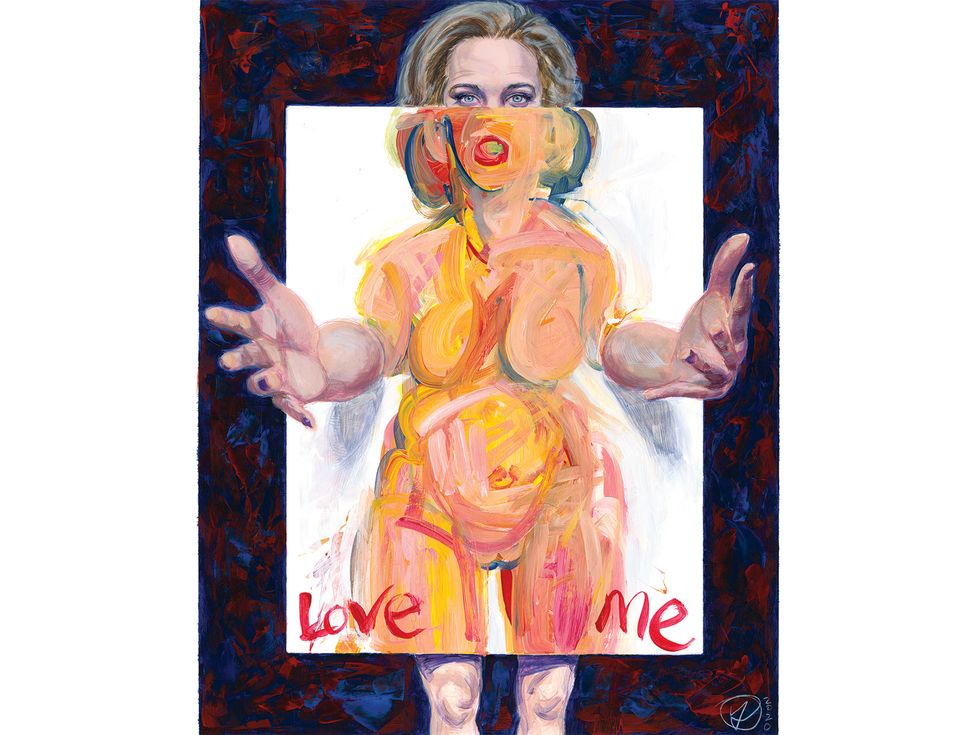

I shouldn’t have left the studio. Some of the paintings have been touched. Plainly, people were touching them without me there, since a number are askew. You use impasto, I remind myself: you want people to want to touch them. The desire to be touched is embedded in the paintings themselves, the raised impasto surfaces, most of the work done rather violently with a palette knife so that you feel, looking at the rough surface of the paintings, life pushing at the edges, life in the phthalo blue swirled with cadmium yellow, in the naphthol scarlet glazed with transparent orange. These paintings are meant to be consumed, eaten with gusto, digested, rather than simply seen, passively, from a distance, with a coldness.

This is how my husband sits on the redwood bench in our backyard, entirely still, watching birdseed vanish from the feeder. It doesn’t read so much as warm absorption, but as a kind of quiet alienation, estrangement.

Simultaneously, I am irritated with myself for leaving the studio to chase a dead end and excited some visitors felt what I wanted them to feel: touch me, touch me. I glance at my watch as the last visitors exit. He’s not coming back. I wonder if I should go get something to eat. I go outside to fetch the new canvases, and bring them back inside the studio to be varnished.

I think of our marriage, the vacuum of silence it is, all the things we don’t talk about gathering weight, pressing down on us over the breakfast table, left unuttered, and I wonder if this younger version of my husband is here to talk, and I mean talk openly, the way we used to talk years ago, like true confidants, rather than with the muted politeness of strangers. All that talk eventually leading us to understand there was no real knowing of each other possible, no amount of talk to bridge the gap between us, between how we saw art, or, for that matter, how we saw reality. How I wanted to stand revealed within my art, how I wanted to be loved, and how, after years of toil in the art world, years of crackers and cheese, he came to understand art was of no more importance than boxes of cereal, all the glamour mere illusion, all the right people saying all the right things. We had invented each other at the start, only to unmake each other over the years.

An hour later, as I’m drinking the dregs of a bottle of wine, there is a knock at the door. My husband’s double has returned. He hands me a brown paper bag. I thought you might have changed your mind, he says, and smiles, his eyes crinkling in the corners.

I take a foil-wrapped package, still warm to the touch, out of the brown paper bag, and unwrap it. Underneath foil, flautas that look like they’re from Mario’s on Telegraph Avenue. Cheese flautas. That Mexican joint’s been closed for years and years. I look up at him. Do you want to sit down?

He nods, and we sit down together at the table at the front of the studio.

Are you…? I hack the flauta in half with a white plastic knife. Warm cheese oozes out of its crisp golden shell, a pale white pool of it on the black plastic plate. I pick up one half and take a bite. It tastes real.

Yes, he says.

Is he lying to me? Entirely possible. I want so deeply to believe he’s my husband, that he’s come to carry me away from my present to return to the past, to start over, to live life over, but better. Now that he’s simply admitting he’s my husband, like it’s no big deal, I realize, with an ache in my ribs, he might not be. I am old, old enough now to be his mother. I examine him as we speak, and I see the differences between him and my husband, little differences, like how his eyebrows are just a smidge narrower, his lashes slightly longer, thicker, and yet I reach over. Tiny differences don’t shield me against the desire to be with him, to be with my husband as he once was. There are ways time makes us, there are also ways it fails to shelter us, ways it fails to offer a buffer against the way we’ve been with each other. He startles, as I slowly roll up the sleeves of his knit blue sweater, hoping to see on his arms those indelible marks of past and future.

Anita Felicelli, Alta Journal’s California Book Club editor, is the author of the novel Chimerica and Love Songs for a Lost Continent, a short story collection.