I was here because I wanted to be. I didn’t hate school, I especially didn’t hate learning. The main thing they taught me, yelling into my face, was that I was wasting their time and money. It did take me a few incidents, and growing years, to allow the words of these wise teachers to work for me: Wasting their time and money? So I got done with their troubles and their finger-pointing at me. At the part-time job I already had—my uncle Jorge (pronounced in easy Anglo, George) ran an industrial laundry he called the plant—and I asked him if I could go full-time. He didn’t have a question, didn’t blink. He said he’d started working before they’d invented school. To him and lots of people I came up around, I was grown, young only en este lado, on their side.

Forty-eight hours a week, 7 to 3:30, and I was making coin. I bought me a nothing-special, four-door Ford—no more bus! I was shifted into the clean area, the unpressed washed sheets and unfolded towels, and that was better too. I loved getting morning café with lots of sugar from Rosa, who’d been working here over 30 years, the same as my uncle, who knew my mom. She gave some to me every day if I got there before 6:50, because at 6:51 she put her thermos away. Herminio, an older man who was from a Mixtec village with a name I could never pronounce, had extra tacos warmed (rolled like burritos) for me at the first whistle break—frijoles with onion and tomate, con chilecito. Life was good like this, and I got paid. The guys I worked with, Juanito and Gerónimo, they were older, sharper, and I liked being around them and learning work and all else. Juanito, who would say he was from El Paso, but really Juárez, though really really San Luis Potosí, was the oldest of us, the longest at the job, which was almost five years. He was either 24 or 27, depending on the day you asked. Gerónimo was 21 and had spent time in prison. He said he was a Mexican Indian from Arizona. Since he didn’t speak English or seem to know any Native language either, I didn’t believe he was telling the whole truth, but I didn’t question him. His face was more wood carving from Olvera Street of an Aztec than skin, so harsh and rough it could’ve been gouged by a machete. The two of them told me lots. Me, I was born at the Texas–New Mexico border but raised in L.A., and I was hungry to learn so much I didn’t know in the real world. Even though I had my most life in this big noisy city, I was more del campo, like an innocent country boy. They told me dicho-like truths about cabrones and pendejos, and they especially liked to be expert about people who worked in the plant.

“Her,” Juanito whispered when Faby walked by, his eyes down as if in prayer. She was pretty and swayed. “She’d be good for 10 babies.”

We laughed. He meant she was a chichona, big in the boobies area.

“Brother,” Gerónimo told him like he was talking to an alcoholic, “you forgot the four legal ones? You want a little illegal one too, you stupid?”

Four children was true. I didn’t know a man could have so many so young.

“That one,” Gerónimo told me of Jacinta, the shaped one who moved like she thought it was crazy for her to be working here. “She goes with the boss.” He eyed me to catch if I showed anything. I gave up nothing. “Your uncle,” he said, as if I didn’t know or hear what he was saying.

“She’s something,” I told them both.

Really my uncle was the one who was something. Or that was how my mom saw him. My mom said he made my aunt pray more faithfully. My mom said it was men like him who made her go to prayers less. Of course that was about my father, who I can’t say I ever knew any better than by a wallet-size photo I once saw. He was always back there in El Paso to me. Probably the kind of El Paso that Juanito lived in once upon a time never really. It did sound a lot better to me, even as I grew up, that she left him there. When I was little, I thought of him as a vaquero, or even American cowboy, either. He was riding hard, moving on so fast the rising dust seemed to be blowing the other way.

Neither guy said much about Isela. That was because they honored her. She was sweet, quiet, calm as 5 a.m., and—no extra meaning in any of these next words like usual—she was married, which was never the end with any other woman. Even Gerónimo might have sighed like Juanito if he knew how to make any soft noises. She was an ideal. Her husband was from Chihuahua, which meant something powerful to both of them.

To me she was small, super cute, and in a way farther away category of life than me: in her 20s, all grown woman, a wild unknown. I was dumb and clumsy, my feet faster than my brain. Anyone would say she was shy. But once the beams of our eyes connected, they got so bright there it could only be a forced looking away. Like magnets pulling, it was hard for me to not turn toward her. The first time I really met her up close was a morning I came to the lunchroom at 6:31, early early—I knew exactly because I punched the time clock—and I went right over to Rosa for morning cafecito. How could I have known that Isela would be sitting right next to her? Never heard of her being there, never was when I went before, even if it was usually 6:45. I’d never come in so early, but this day I did. Like I just had to. I didn’t say a word, she didn’t say one either, and yet I met her and she met me and we met.

Once Hermi gave me a couple of tacos at break like always, I went in the lunchroom like never. I didn’t go there for breaks or lunch usually. I struggled to not keep staring over. She was with the women she worked with, not chatting like they were. She wasn’t looking back at me either, but her not chatting or looking, to me, came out the same. After, I swore I could even tug at the pull of her eyes when she was working over there, even when she couldn’t see me if she tried. That’s how crazy I got. It was an illness.

Sometimes the three of us guys would be sorting through wet sheets to lay out for pressing in the mangle, and though I could see and hear Gerónimo or Juanito talking, it was like I was in another room, their mouths moving far away from where I was.

“¡Despiértate, vato!” Gerónimo’s voice was like a slap.

Juanito was nicer. “Up up little babies don shoe cry…” He knew the rest even less.

I didn’t say anything. I lied that I’d met someone. I was thinking Isela but I didn’t say it. I exaggerated what happened, which was nothing but in my head, what I dreamed, played down that it meant much to me. Then I said she was kind of like her, like Isela.

“You are a baby,” said Gerónimo. “Better you break your uncle’s cookie jar.”

“You don’t want to go there,” Juanito said. “You can’t get married so young.”

Gerónimo laughed at him cynically. “Don’t make a baby. Make sure she’s not already married.”

• • •

I didn’t go to church anymore, hadn’t once since I was maybe 10, but I’d say I was like kneeling in a chapel, eyes closed, or focused on her, praying. Prayer all day, concentrating hard, only her, getting myself closer, purer in thought. I was dazed. Yet in another part of my mind I knew it couldn’t be like praying at an altar, because, since she wasn’t a saint but a real girl, a grown woman, Isela, who was years older than me, who was married, this could only be lust. It wasn’t and couldn’t be what I should want, what to pray for, what God would grant me. My mom once told me she still believed in God (and Santa Misa even though she stopped going to church) but quit praying as soon as she could. Her sister, my bad uncle Jorge’s wife, told her that that was why she lost her husband, which was my father. My mom rolled her eyes and said my aunt lived in a sad fantasy world because no God would want her married to my faithless uncle. All this just got me confused. Like I was here, now.

It was Herminio who rushed over to me while I was pushing an empty laundry cart to where we left empties. He’d never come over to me unless he had tacos to give me. He’d be happy, like I was an old person and he was the young one doing a good deed. This time, late in the afternoon, not smiling, secretive, whispery like he had to get to me alone, he wanted only me to know: la señorita needed a ride. He almost scared me with the news. First of all, how did he know about her and whatever she was inside my head? I hadn’t told even Juanito or Gerónimo. It also right then came to me that I didn’t really know why Hermi gave me tacos every morning break either. I only stared at him speechless. Not one word to say to him. And as quickly, and as suddenly as he came, he turned away and went back.

I didn’t tell either Juanito or Gerónimo about this either. I didn’t ask them nothing about what to do or what not. My head was down for the last hours of the day. When I’d look up at them, I didn’t too long because I didn’t want to get any questions, laughter, mocking, sarcasm, wiseass advice, a stupid song, snicker, any hilarious joke. Once or twice I knew their looks at me and each other were about me. I wanted it to be so nothing to me, to care so little, I wouldn’t see them, I wouldn’t hear them.

After the whistle, I was eyes open in my car, happy to be going. I didn’t even like my car anymore or the money I owed my uncle—it’d been his—to buy it. Ashamed that I could be like this, I was half-wanting it to stop. I thought that maybe I wouldn’t come in tomorrow. I could call in sick. Maybe not come back at all. Another job. All these kind of thoughts popped as I pulled away heading to my big brother’s, the carpintero, except not a good idea because sometimes he’d have been drinking all day and high once he got home when he didn’t care about anything. Or maybe to my big sister’s, except she’d be running after all her kids and her boyfriend’s kids and ones she babysat for money. And I didn’t want my compas to know all things with me out of school weren’t all perfect, so not them. My older older sister maybe, but she was so perfect she was like a priest, except she was female and anyway I didn’t want to confess love or lust or hear about me from her either.

Then I saw Isela walking on the sidewalk. By herself. My heart hit the brakes. I slowed but I couldn’t stop because of the traffic behind pushing me to move steady. I pulled into a red zone, near a fire hydrant, ahead of her. She wouldn’t know it was me so I slid half over and leaned in the rest, buzzed the passenger’s window down and called out her name. I said her name like we were great pals, knew each other for years. We’d never talked one word. I probably was supposed to pretend I didn’t know her name. She may not have known mine.

I got myself back to my side of the car, swung open the door, and stood, looking over the top.

She stopped and didn’t move. She stared at me, barely looking. Then, “Oh, hi.”

A car blasted its horn at me.

“I hope I didn’t scare you,” I told her.

Another car wove wide around, a couple of jerks called me names.

“I saw you walking.”

“Yes,” she said. She looked at me for a second.

I couldn’t breathe right. “I was thinking. A ride. To home. Or where you’re going, where you need.” I wanted to sound OK. “If you want.”

She came to my car and opened the door and she sat inside, in the seat. “Thank you,” she said. She didn’t look at me at all.

I could barely think of what to say. And she seemed stuck, too. She apologized and thanked me too much, too quietly, directing me as I squeezed back into traffic. Our talking was a lot like the driving. I could barely pay any attention to where I was going, where I was, only the straight aheads, the lefts, the rights. That she was sitting there, that itself was beyond my mind’s ability for much else. Then we were there.

“Wait, no,” she said suddenly. “Not here. Farther, more ahead.”

I rolled forward. “More…more still.” Finally she said this was fine, told me to stop.

“You’re OK here?” I asked.

She was smiling. “Yes, yes! Thank you!”

I got to look at her. For uninterrupted seconds. I could have swooned. I couldn’t believe I could have ever met this girl, this woman… “If you need a ride tomorrow,” I said.

She looked at me for more than one second, because she was happy, then nodded. “After work?”

“Sure!”

“You can?”

“At your service,” I said in that bowing, humble Spanish expression.

“I have to go now,” she said.

“Until tomorrow,” I told her.

Nothing looked the same. I was so dumb, I didn’t know I’d been living in paradise! I turned up my music offensively to all outside my joy, wishing I could throw gritos of love, cry the weakest of masculinity, the fiercest. I drove, air beneath me.

• • •

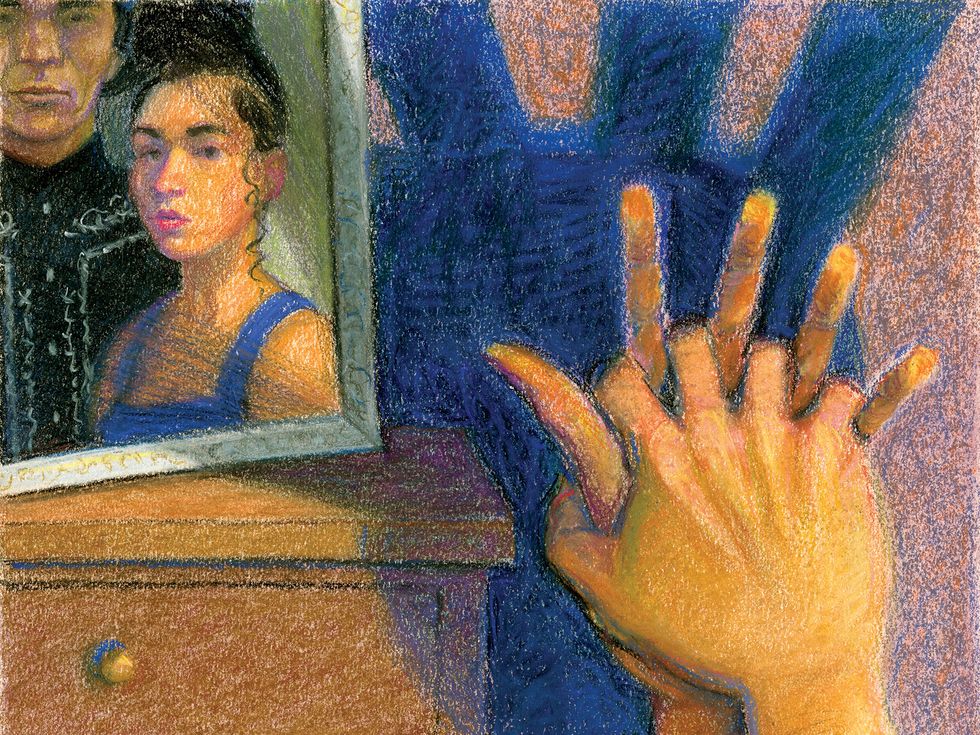

I got to work the next day way early, about the same time as Rosa with her café, and angled myself to watch Isela punch in. She wouldn’t look at me until once, a moment smaller than a second that flooded my eyes like a camera flash, and then she put a finger to her lips, her eyes down, so sweet with me in them, to tell me to shut up, to say absolutely nothing, to let nobody hear or see nothing. I understood!

I loved my job again. I loved my car again. I loved for the first time.

“What’s going on with you, vatito?” Gerónimo asked me sarcastically. “Yesterday you were fucked up like a tecato with the shakes.”

“What do you mean, little dude?” I said. He was older, more dangerous, and looked a lot of things more than the other older guys there, but he wasn’t taller.

Juanito, who was as tall as a tall white guy, laughed. “Somebody took a nap.”

“Maybe he got a raise from his uncle,” Gerónimo said.

He was always saying I made more than they did. I didn’t think it was true, but I didn’t want to risk finding out by comparing checks.

“You get a raise?” he asked.

“He’s probably happy because he bought a puppy,” Juanito said.

Jacinta swayed to the bathroom.

“Kiddy kiddy,” Gerónimo said quietly, meaning kitty. “You get a raise, too?” he asked me.

“I do wonder if he pays her more,” Juanito said about Jacinta.

Gerónimo could never be light. “You ever see her?” he asked me. “Like him and her not here at work?”

I shook my head and decided to go get another full cart to bring over to us. Herminio met me, excitedly it seemed to me, asking if I was all right. I said I was, as regularly as I could, not wanting to give anything away. That seemed to make him too satisfied. He told me he had tacos for me. He always did, so why did he have to say that? I thanked him and wished I meant it more, but it was too strange. It didn’t matter though, quickly forgotten.

What mattered was the end-of-the-day whistle blew and I got to go to my car. I saw Isela come out, and I knew she saw me too. She wouldn’t look, but I’d say she was walking faster. I understood. Better that nobody knew. What I didn’t know was how long to wait before I left for her, and it was hard for me to sit still. I couldn’t wait too long, I was sure, but I didn’t want to miss her either.

I think I came across her sooner than last, and this time I honked. Two little taps, beeps as short and cute as I could make them. She still jumped some and seemed to look around before she came to the passenger’s door and scooted inside. I pulled away from the curb and into the mess of traffic.

“I’m sorry,” she said so quietly. “I don’t want people…anyone at work…”

“I agree, really.”

“It’s the gossip,” she said.

“Of course, I understand the worry. We could pick a place. Farther up? If you want. And wait for me there, better?”

She chewed her lip.

“Same thing if you’d want me to get you in the morning…”

“No no,” she interrupted.

“…so you don’t have the long walk.”

“No,” she said again. “This is nice, very kind by itself.” Then she looked over at me.

My God, like I’d never seen a woman before. One who smiled in my own car!

“Thank you. I’m so happy that you aren’t bothered.”

“Bothered? Impossible. I’m happy!” So happy I blurted out this: “You’re so beautiful!”

I’m not sure if she blushed—she was a morena, so who’d know?—but, her face downward, she smiled like I’d never glimpsed. “Thank you,” she told me.

I felt stupid, a teenager. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I shouldn’t have said that.”

She shook her head certainly.

“I don’t want you to think…,” I went on, not sure how to say that she was a grown woman, a married woman, and I was…that I just quit high school. The real. I said, “…I don’t mean to be disrespectful.”

“No,” she said, eyes on me. It was, even, as if she’d moved closer. I swore I could see stains of green in their brown. “It was very nice of you.”

I loved that there was traffic and we had to move so slow. Also I didn’t try to avoid any stupid driving in front of me. I didn’t remember a single turn or stop. How long it took me to get to her place. Where I was, where I was going. I’d already forgotten the other facts. Reality. And I didn’t think she minded. Before she got out of the car, she hesitated. She looked over at me. It was the longest time yet. I thought she might reach and touch my hand. She didn’t. That didn’t matter either. I couldn’t have taken that too.

And so it was for days that floated like months. Hidden. Nobody knew. I didn’t stare at her with my long-glancing eyes, only with prayers or in sickness. I worshipped her. It was real or fantasy and I didn’t care which because…say I were to die. My life felt full.

Hermi was bringing me three tacos instead of the usual two. Why? He winked, the kind that was between us. He said, “You are young, I’m old. I’ve eaten plenty. Especially in the morning. I need less. So now you have one more. You need it.” He winked, or it was something like one. I didn’t really understand, but tacos weren’t so much.

Gerónimo kept digging for things. “So what’s going on, vato? You been acting all over the place. You get a bigger raise?”

I told him I wished he’d quit saying that shit. I didn’t make any more or less than him.

“How much?” he asked.

I looked at him and shook my head. I was about to say when Jacinta popped into sight and he got distracted.

“That is a rich and tasty chicken,” he said, watching her walk as long as he could, until the bathroom door behind her closed. He took more time after. “What do you think of her, vatito? You like?”

I didn’t like this subject either.

“Or you can’t let yourself because she’s your Tía Sancha?”

What was I supposed to say? What could I possibly say?

• • •

Isela said I should come in.

“Where you live? Your casita?”

She’d touched me politely a few times by then, but this time it was like my whole hand by her whole hand. Really different. Her place was in the back, behind a bigger home. You had to get to it going around trellises of flowers—and then came cornstalks. The people in the bigger house grew corn in their backyard. I’d never seen that before—never been so close to growing corn. Mostly cans, on shelves. If you didn’t already know it was there, you’d never see the little casita at all. The door we came through was more for a shed, plywood so thin it didn’t seem wooden, and instead of a doorknob was a cabinet handle, above it a latch and hook for a padlock that kept the door closed.

It took me a few inside to figure out that the ceiling was lower than normal. I wasn’t as tall as I felt. Things were nice enough from the floor up. A saggy sofa with a matching stuffed chair. A picture of Jesus, the one everyone owned, a couple of decorated crosses and a plain one surrounding it, a mirror in a gold-gilded frame. A narrow stove and short refri. The table was wrought iron, an outdoor kind. Above it was an old photo of Pancho Villa, a famous one with straps of bullets crisscrossing his chest. Three plastic lilies in a vase.

“Do you want a beer?” she asked me.

She didn’t look as small. It couldn’t just be the room’s shorter height. There was so much more of her here. Bigger than her life at work. Than my life anywhere. Than me. I was so excited and I was terrified: we never once talked about the obvious subject.

“Or a soda if that’s better? I’m having a soda.”

“Soda. No, beer.”

She brought me a can. “You hungry? A quesadilla?”

“No, nothing, thank you. You don’t have to cook…”

I was on the couch when she sat. Close to me. She almost got my mind off the collection of ceramic gallos and the metal horses on a table sharing the space with an old lamp making a yellow light.

“So,” I said finally, “your husband…” I didn’t know why I said this. It was the last thing I wanted to talk about.

“You don’t worry,” she said. “Please?”

She was so close to me I started thinking either less or more, I couldn’t say. I definitely didn’t want to know her husband’s name.

“I’m so happy when I am with you,” she told me. “Are you happy?”

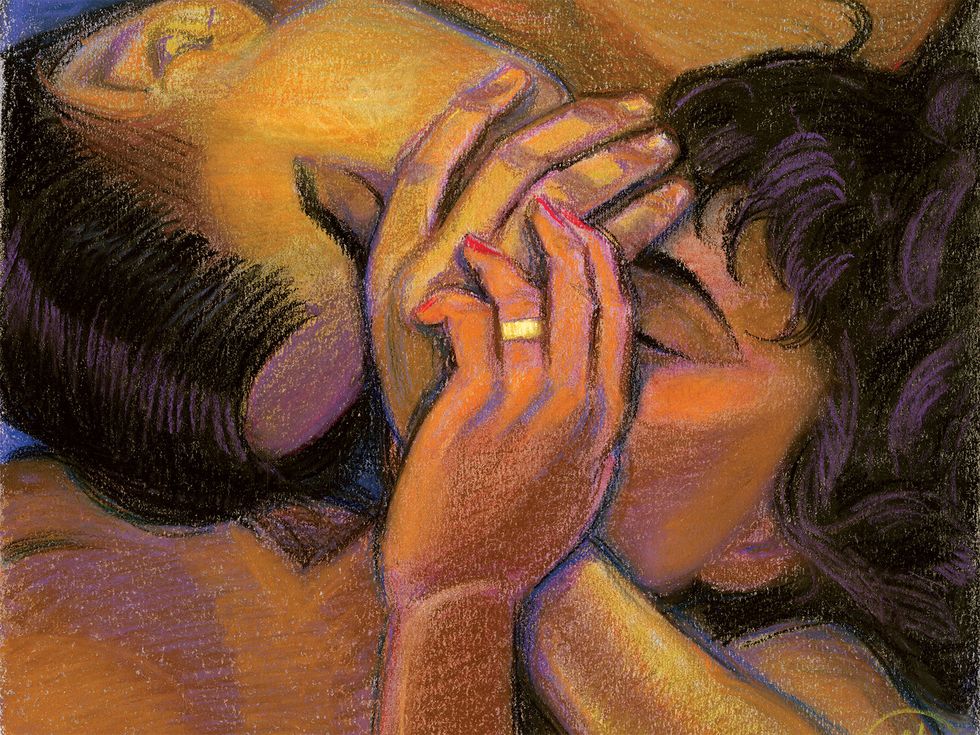

Happy wasn’t it with me. When she kissed me, I began circling earth. Nothing about Isela—her lips, hair, cheeks, neck, back, waist—was like anything I’d ever touched before. When I took in normal air, I landed and my legs were running. I wanted out that paper door before it opened in at me.

At work the next morning, Isela didn’t hide looking at me when she punched in. I was the one who looked down and away quick. I felt her watching everywhere outside me. Inside me I told her to stop it, or to be careful, to not let anyone know. Nobody knows anything, we hadn’t done anything, my voice said, in no words, to her eyes, not staring, watching me. When I looked around, really, nobody was seeing anything, especially coming from Isela.

“Are you talking to yourself?” Juanito asked me.

I wasn’t sure.

Gerónimo said, “Your girl tell you she’s pregnant?”

“What?” I screamed, or just about. Way too loud for sure. I overreacted. I thought he knew about Isela and me, that they both did, and the rest. Which wasn’t possible.

They both laughed at me. I don’t know what the sound or movements that came out of me were.

“Vato,” Gerónimo said, “calm yourself down.” He cracked a smile. I had never seen a smile in his carved face.

“Even if your girl just told you she’s having a baby, you’re in good shape if you calm yourself,” he told me. “Almost always a lie.”

I didn’t know which was stranger—him smiling or him offering real advice, dumb or not.

“Just don’t go crying like a girl, vato.”

He was back to his normal anyway, and at least his distraction settled me.

“Seems like you guys are on me a lot,” I said.

Gerónimo kind of stopped everything and, nodding, did a whole check-me-out thing.

“No, it’s nothing bad,” Juanito said. “We’re just seeing you.”

“Seeing me?”

“We got no uncle here,” Gerónimo said.

It took me a few seconds to realize that he said that to Juanito.

At break I was afraid Isela would come over to me upset, and there’d be nothing but eyes on us and gossip. So I headed where most went, outside to a lunch truck. Hermi chased me down. “You forgot these, mijo.” Three tacos. He stopped, he breathed harder, but not from being out of breath. His voice kind of trembled. I swore all this was about Isela and it made me worry more. Before he left I told him to wait a moment. And I almost asked him. I said thank you instead.

I fought hard against picking her up after work, forcing myself to walk away slow. That I shouldn’t. I didn’t go into my car too fast. I stalled many extra seconds waiting to turn on the engine. I used the brakes. I almost decided I would take another route.

I didn’t tap my horn. No party-time blast, no cute beep-beep, just silence way ahead of her where I could pull over in a no-parking space. She rushed to the car, almost tripping a skinny old man walking with a fat dog, and when she got in, she started sobbing.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “Everything’s fine. Everything will be fine.”

She didn’t stop.

“Please, Isela,” I told her.

She wouldn’t say a word.

I couldn’t talk either, so I took off and I got to her drop-off area. I didn’t know what to do. I decided to stop close to her casita.

She looked up, her eyes on me through a waterfall. “¿Ya no me quieres?”

“Only too much,” I said.

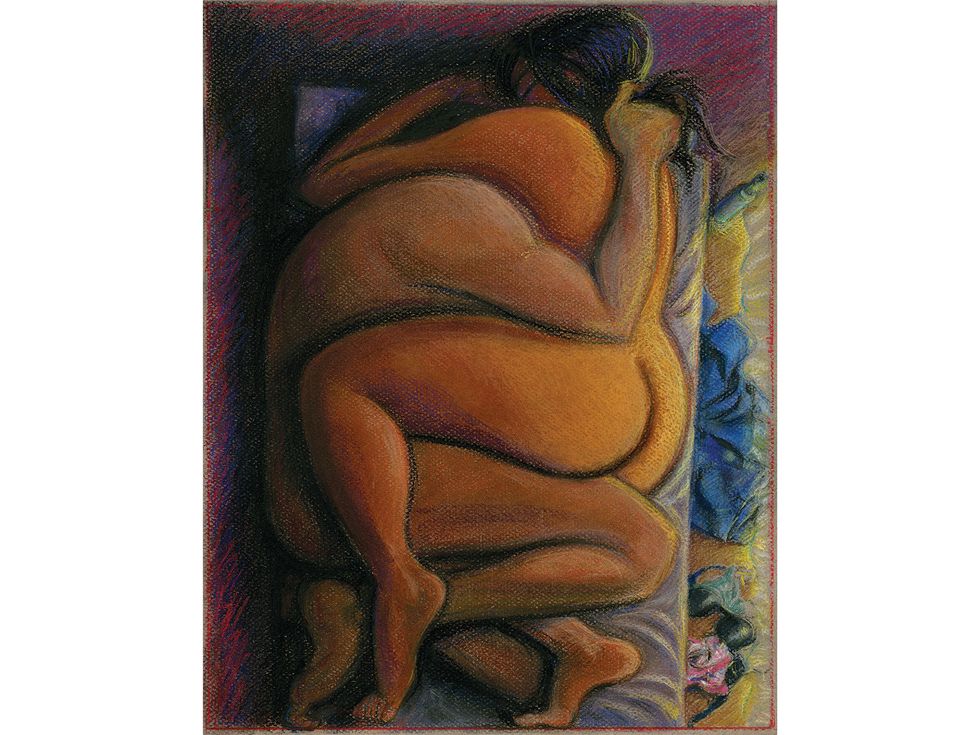

She slid over to me and soaked me in tears, crying and kissing. I parked the car not so close. She moved fast, but I kept up with her easy. I thought we would slow to that couch, but no, we went through a curtain where it was nothing but a closet of a room, empty walls and all bed that was a mattress, sheet, pillows, and a blanket, a ceiling so close it made us seem bigger than whatever was up in the sky on its other side.

“It’s OK,” she kept whispering. “All is fine, don’t worry.” She was the voice of heaven. “It’s us. I love you, I want all of you.”

I couldn’t see anything but her, and it wasn’t just the tiny room. I didn’t feel anything but her. I didn’t know anyone but her. It didn’t matter where we were, didn’t matter where I was going. If there was an answer from God, if I was in paradise or hell, if there was a should or a shouldn’t, if it was sickness to hear love and float like a bubble of tingling starlight.

• • •

For who knows how many days or weeks I moved like everything was as it had been and always would be. When I got my sugary morning cafecito from Rosa, even though I saw Isela’s eyes stuck on me clocking in, I didn’t get stuck back. I was numb. I was in heaven or I was in hell. I didn’t go toward the breakroom to see her, or run to the lunch truck at break to hide my eyes, my thoughts. I didn’t want to get stupid about us. We were a perfect secret. When Hermi brought me tacos, I took them for granted. He was always so pleased to bring them to me. They were good for me, he told me, holding the foil wrap of them, just right, and I would really love them if I were as hungry as he was. I said he should keep them if he were hungry. He shook his head hard. Once I was, he said. These were for me, that’s what he wanted. I needed them, he said. I laughed because they were tacos and it didn’t make any sense, and he laughed with me too because I laughed. My uncle, he told me, liked them too. My uncle? Twenty-five years ago, when he first came to work here. My uncle was my age then, while he was old even then. We both laughed again.

After break, in front of a bin of just-washed sheets, I was trying to talk about Isela without saying it was about her. Sometimes I made as much sense as a drunk, and not even I could understand me. It was the secrecy, our bodies. That she was married.

“What’re you talking about?” Juanito asked.

“That he’s your wife’s Sancho,” Gerónimo told him.

“That’s so funny,” Juanito said. “You’re like TV.”

“You better check the color of the eyes in the next chamaquito who pops out,” Gerónimo said.

“What’re you talking about?” Juanito asked me again.

“Nothing, I guess,” I said. Then, “Just how you know what’s love.”

Gerónimo laughed. It was a gut laugh, surprised him like a pointed toe boot hit him there. He never laughed.

Juanito took me serious, like we weren’t in an industrial laundry sweating in 100 percent humidity and maybe the same in heat, giant fans swirling air like an outdoor wind and we were really on top of a mountain. He was gathering words for an answer when Gerónimo, his carved Aztec face back to usual, beat him to it.

“A knife too sharp to feel until it does,” he said. “Lots of blood.”

“That’s hate,” Juanito told him.

“También,” said Gerónimo.

We all saw my uncle talking to Isela in the corner they worked. Jacinta was with her. She and my uncle walked her to the office.

I went for another full cart, taking the empty first.

Hermi said she was sick and wanted to go home early. He said, in that to-me-only voice, that it was her husband. Something, he said, always something.

I decided to go for more, to ask what if she were messing around. They knew nothing of me and her, suspected nothing. Nobody did.

Gerónimo made two fists and pulled them toward his hips a few times.

“Isela?” I said.

“I thought you were talking your tío’s cookie baby,” Gerónimo said.

Juanito shook his head. “Easier to get free rent.”

“Her old man’s old country,” Gerónimo said. “He’d kill her.”

“Not him?”

“Both.”

“I’d stop breathing and die,” said Juanito. “Not her.”

“It’s morning,” Gerónimo said, seeing her leave the plant. “Probably that kind of sick.”

“Lots of ways to be sick,” Juanito said, “but a good bet if she were my wife.”

She came in the next day, and I picked her up walking after work and we went into her casita. We didn’t talk a lot ever, only what said we were happy when we were together. Besides, I knew so little. I didn’t even know what I thought I knew very well. We went to the bed and we were like the only two in a world that nobody else had discovered.

“I love you,” she sobbed, clutching me. The words weren’t new. She said it over and over and often. We hadn’t talked about why she’d gone home the day before. Her tears rolling down my arms and chest, I suddenly had to sit up. Everything, every thought, bigger. It seemed my head could crash through the ceiling if I stood too fast. I sat up in the bed, suddenly, because I was seeing their marriage portrait. I ignored it all the time, there for tiny seconds, little bits. Only once with my hands on it too, when she’d gone to the bathroom, and I got up to see it close. She’d hidden it under a layer of blouses on a junky, child-size set of drawers. I didn’t look long because I couldn’t, and I didn’t want her to catch me. Framed in a polished tin, of both of them, I only really saw him in the blur of my curiosity. He was even blurrier in my memory. His black dress charro shirt with white stitching and buttons, his black hat with a silver studded band. His face didn’t smile. It was carved as rough as Gerónimo’s, but it was alive, too, like Juanito’s. Its pride and confidence as harsh as a glare. That was what made me sit up: the image, not for prayer or fantasy, was pulling at me to stand. Below, I felt Isela tugging at me. She wanted me to lie back down, to hold her. She loved me, she said. “I love you, too,” I said, kissing her like she was mine.

Dagoberto Gilb has published nine books of fiction and nonfiction. A new collection of stories, New Testaments, is forthcoming from City Lights Books in fall 2024. His fiction, “Answer,” appeared in Alta Journal 11. Born in Los Angeles and raised there by his Mexican mother, he has lived in El Paso and Austin and now resides in Mexico City.