Efleda slipped from her mother in a twilight fog, hair dark and a squall to rival the waves. The ease of her birth became a frequent story, a boast for parents to tell at parties.

“We were driving,” her mother would say, eyes glittering, bouncing Efleda on a hip, a knee, stroking her cheek as she slept in a bejeweled bassinet, “and we thought we’d make it, but she was too quick for us!”

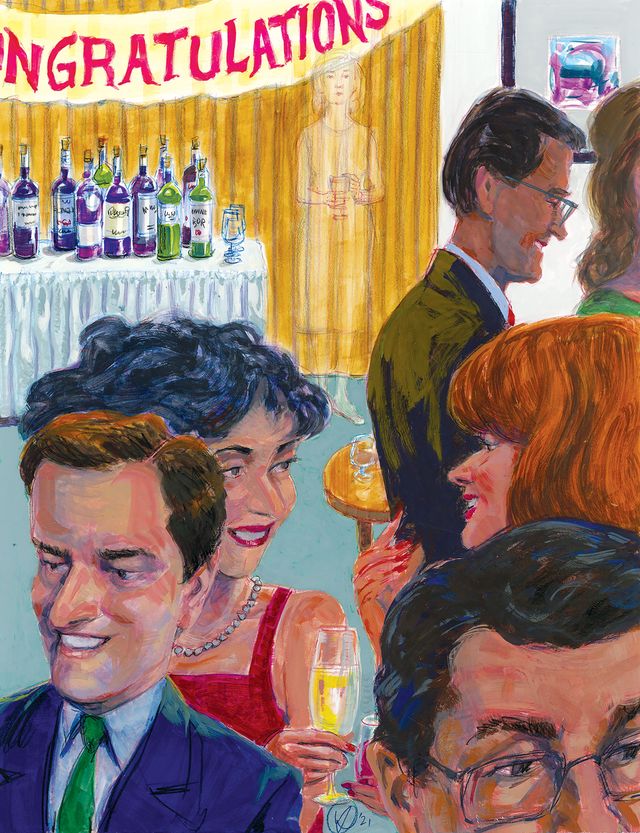

She would raise a glass, bubbles drifting toward the surface, and toast her daughter, and stroke the girl’s hair, laying it flat so as to kiss the dark, smoothed run. And the guests would laugh, and smile, and nod agreeably, as if they knew something they had not before.

In this way, the edges of the narrative blurred, the years softening, rosy and fabricated in their recount.

A peculiar practice of Efleda’s parents, something to which they would remain affixed so long as the girl was small, was to have Efleda always nearby: at a party, on an outing, by a sickbed. They kept her close, but never really did they speak to her, and not often was she held. Assign it to the nerves of a first child, or increasingly as the years passed, to what was becoming clear would be their only, and in the way most things were precious so too was Efleda, not for some particular trait or the merits of personality, but for her rarity, as artifact, an insect in amber resin best examined against the light.

The real story: a vacation, some exquisitely out-of-the-way place to which one must helicopter, to which her parents did, the gem replete with linen napkins, oil-rich soaps, brushed teak decks overlooking the ocean. Efleda’s mother, hugely pregnant, and her father, hugely proud, sat together at three-course dinners and ate at the pace of those accustomed to luxury. They were in love, aglow, but then a sudden pain a month too soon, and helicopters did not fly in fog.

They borrowed the innkeeper’s car, drove until they could no longer, found themselves at a piney pullout, the headlights cutting a white soup over the fog-socked road. Her father turned the wheel, gravel distinct under the tires, and her mother pounded the seat, dust plumes rising, pull over, pull over, she’s coming.

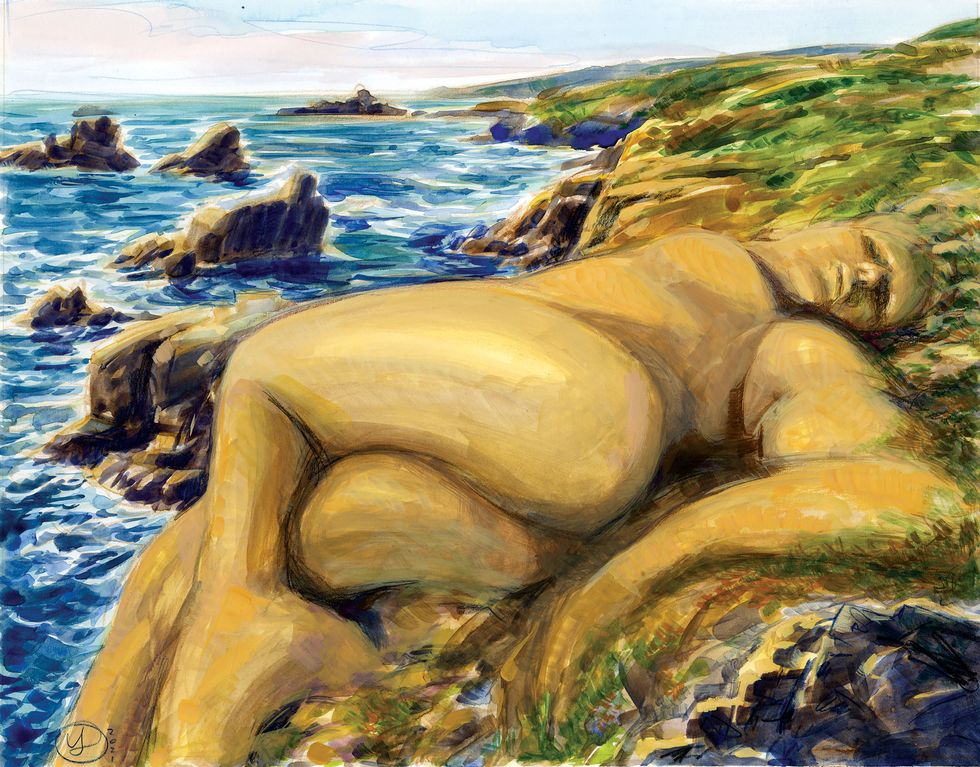

In the place Efleda first became Efleda (to be: a separation), sandstone sprung up from the sea, holes as big as caves, its surface etched in gridded rivulet, the cliffs lacelike and mottled. Alien enough, this rock, that one might think it diseased were it not for the gentleness of the wear, the soft curve of each edge, would-be crags burnished in the surf.

Efleda’s mother squatted, held herself in the frame of the open door, and pushed, sure this was her death. Her father crouched behind, a hand steady on her back. The sea quieted. The breeze stilled. In one collective breath the land beneath them swelled, and shuddered, and in its exhalation came the fine, high wail, her first, and then Efleda, body coated in her own slick, face wetting in the rapidly collecting fog. She fell into the basket of her father’s hands, and the cries thereafter were like bells, a tolling, a clarion call skipping over the tiny beads of water, through the fog, to the sea.

Her father laid the tiny head over his shoulder, facing Efleda to the ocean, to the strange cliffs. He took his wife into his arms, and they wept around the newborn.

What they did not tell at parties.

The baby grew. Her hair fell in dark, heavy curls, and she began to think and talk, to ask questions the way children do, when life is an exercise in articulating the world and themselves, in discerning any gap between. She walked the halls of the large house, which was old and built of adobe, her fingers trailing its boundary: walls, filigreed cabinets, porcelain statues topping the side tables, their faces hand-painted in pastel and sealed over with a finishing glaze. She drummed the wrought iron on the porticoes, finessed the furred red bark of the trees that rimmed the back garden. Like she knew of some enclosure she could not see, Efleda found the edge, and held herself against it.

Her hips widened and her hair thickened and her body softened and angled as bodies do when they grow into women. People took note, at parties or shopping at the store, oh how you look just like your mother. A special curse, Efleda decided, to look just like one’s mother, as if her future walked always next to her, pulling the milk down from the shelf, loading the paper bags into the trunk of the car, a blueprint, the way clear.

Efleda was an obedient child, studious, quiet, preferring to observe rather than participate. It was a safer choice, to hold oneself separately, and by so doing, limit the influencing power of the world. By this same character, and not of her own intention, she became for others a prop, more placeholder than girl, a walking, talking idea of a daughter. At family dinners, conversation molded around this fact, her father asking questions with the answers built in.

“Effie, did you like school today?” he would say, and her job was not to consider any response but rather to affirm the implication. Meals were worksheets, bedtime a script, as if she were learning an obscure and unnatural language, her instruction rightly planned, repetition breeding fluency and grace.

“Goodnight, Efleda.”

“Goodnight, Mother.”

“See you in the morning.”

“See you in the morning.”

At night, alone, Efleda lay in bed and stared at the plaster fixture on her ceiling. She followed its outlines, its intricate shadow, her gaze a single, tracking dot. She wondered at its heft, at what would happen should an earthquake come and break it from its mount, the weight landing in the soft bowl of her sleeping belly. Dead from the impact, insides turned to pudding, she would lie in the rubble like a doll. Only after many days would someone find her, scoop her up, and ferry her away, and only then, at some facility, on a cold table, would anyone notice the blood purpling across her hip.

Efleda felt certain, somehow, even as she imagined it each night, that her death would not come this way, that the meticulous decoration of her parents’ house would endure, or, if it did not, that its dissolution would not take her with it. It led her to consider, for the first time, how she would fare were she to step beyond the garden’s edge, were she to venture into a world without her mother always near.

Efleda finished school at 17. She presented her parents with the certificate, at which they cooed, taking it from her to pass between them and hold aloft. They threw a banquet, so that they might exclaim to their friends of her accomplishments, a night of toasts and guffaws and happy claps on the back. Efleda stood in the corner, next to the table of wine, smiling, nodding, thumbing the rim of an empty glass until it sang a low, hollow tone.

At last, the end of the guests departed. Her parents put themselves to bed. Upstairs, Efleda pulled a suitcase from her closet. The glass tones hung in her ears, an imagined symphony note by silent note. How did they make that sound, with nothing inside of them? In the lid of the suitcase, under the bagging netted lace, she folded a lifetime’s worth of birthday money. In the body she set an extra pair of shoes, two sweaters, several pairs of socks. She lashed the bulge flat with a satin leash, clipped closed its silver buckle, and set it in the front portico.

In their room, her parents lay belly-down in bed, snoring lightly, faces turned away from each other. Her mother wore still the champagne sequined dress, her father shirtless in his underwear. Efleda stooped at each side of the bed in turn, kissed their cheeks.

“I’m going east,” she told them. “Over the mountains, to see the country.”

Her mother shifted and sighed. A dribble of spittle ran down the satin pillow.

From where the air thinned over the Rockies, to the dry heat of the Gila River, to the sop of backwater bayous, Efleda moved. She rode chugging trains and buses that smelled of sour milk. When she was tired, she slept, and when she was hungry, she ate. In the summers, she spent her nights in open fields, and in the winters she rented inexpensive rooms in squat motels. When her travels took a lucky turn, she slept on the couches of benevolent strangers. This was rare. Mostly, she took to the world alone.

Like a magnet held against another, fields oriented to repel, Efleda reliably skirted the edge of her home state, edging near with a dependable frequency, close enough to see the border, but never to cross. Like a compulsion, she would find herself in the Nevada Sierra, or on a lowland farm in southern Oregon, or once, in a white-hot RV park in Ehrenberg, Arizona, where she sat on the riverbank, in the heat, for three days. The water ran dirty with light flotsam. Brown river jelly clung to her ankles. She was close enough to California to swim to it, so naturally she napped, fixed on the white Arizona shore, sleeping away her afternoons in a dark, swamp-cooled cabin. At sunset she sat out and let the gnats nip her, staring transfixed at her legs in the water. She imagined herself a cypress, incongruous in the desert but by some miracle still there, twinned trunks drinking from the river, each leaf an eye trained on the opposite bank. She was keeping watch. For what? She’d know it when it came.

When she ran out of money, Efleda worked. Sometimes she was a waitress. Sometimes she was a checkout girl. Once, in a sleepy Connecticut town, she was a librarian’s assistant, and for a whole purple summer spoke hardly at all. Sometimes she rented herself out, her body a soft respite for roadside men. It was not markedly different from the monotony of retail or the impatience of a hungry diner customer. She was both careful, and lucky, and never found much trouble. She would think back often on this employ, recounting the nights in the bright daytimes after, and always she pictured the bodies from above, shadowed dimples beneath the fingers where they gripped her thigh, the steady rock as he worked himself, whoever he was, up and over the edge. Riding on a bus or ambling along the soft shoulder of a country road, Efleda would think of it. She understood that she should be ashamed, that the difference between the private world of her mind and the public place around her should be horrifying. Instead a kind of quiet pride emerged, the root of it a thought, that her body could be something good, that for someone else she could serve this purpose—a pleasure, a comfort—that she had never served for herself.

Months stretched to years, and years to decades, and on her 35th birthday Efleda awoke in Deming, New Mexico, to a hot whisper of dust skittering over the road outside her window. She pulled on a thin yellow dress, folded up her sleeves, splashed water on her face, and pinned her hair into a bun. Outside the little apartment, she walked the two blocks to Betty’s Diner, silt collecting across her sneakers, the wind whipping a fine particulate into the spaces between her teeth.

At work, Efleda watched the wall-mounted television, bundling silverware in white paper napkins, stacking the bundles on a plastic tray. There was a beauty in it, she thought, as one thinks on the anniversary of one’s existing in the world, a peace to living this way. Time didn’t pass, not really, so long as she kept moving. There was no need to think about what came next, so sure she was that something would. It was the problem with people who stayed in one place. They had to live in it, to look at it every day, all that time passing them by.

A banner flashed across the screen, and then footage of a burning forest, a development engulfed, a clutch of crowding civilians herded into a canvas-roofed truck. Efleda set down the fork she held, braced her hands on the counter. The newswoman’s mouth moved on mute, words unfolding in stuttering white type across the bottom of the screen. A line of heavy fencing unfurled along a mountain highway, jacketed dogs sniffing the perimeter and towing guards behind them. Crews stood in the dozens to erect the fencing, posts wide and black and set deep in the dry earth, the top a glittering razored spiral. Efleda blinked. A well-lit studio then, and a clean-suited newsman, his head canted slightly to the left. Pity, Efleda thought, or solace. Next to his face, a map, red stars dotting its scape, portions of fence yet to be completed. Evacuation, the captions read, mandatory exodus.

The segment cut to a satellite view. Soft, white smoke carried out over the ocean, more than half the stretch of the state in some sort of fire, the coastline obscured in sweeping gray. California did not end but rather faded by ash into the Pacific.

Efleda should have thought of her parents, of the haze of distant family, of those she knew still living in the state who might now be trapped there. Instead, her mind sprung to the day-green hillsides, their oaken folds, the pin-tipped redwoods and what moted dustlight hushed the floor beneath them. Instead, she thought, or remembered, or concocted (the difference: what?) a crash of steady waves against a good, high rock, the spray sent skyward like a crest of flocking sparrows, an arc, a weightless hang before the dive and then the dive itself, a mind with many bodies sinking back down to the earth.

Efleda pulled her name tag from her chest. Efleda lifted her purse from the hook. Efleda did not hear the shouts behind her, Betty protesting, the fall of the pyramided rolls. Instead, she heard the bells above the door, those that clanged lightly if at all, the soft set as she closed it behind her, gentle, not from any deference but from the function of habit, her mind was already gone, on the road, on the dirt, on the sunset ahead, true west.

By rare bus, by her feet, by her thumb, Efleda dodged her way home, darting against the current. People collected along the roadside, in cars, on foot, a slowly fleeing caravan her opposite. Many had made this migration before, she knew, in droves and more than once, the novelty now not the route but the direction of its flow. Stories floated out from the travelers as she passed them, a shaking ground, a smoky sky, the water table tapped and earth beneath it dry as stone.

Those in the eddy found themselves continuously stopped, lined up, put on lists, ushered through endless corrals. Via Jersey barrier blockades and ill-lit offices they were funneled, asked to present identification, ordered to open their mouths to demonstrate their freedom from infection. The guards, uniforms green or blue or a bright safety orange, pulled their things apart, swatted their bodies, stretched wide the openings of their bags. Never, Efleda thought, had it been so hard to go home.

She held her mouth in a flat line. She spoke only when spoken to. She kept herself small with a hug at the elbows, camouflaged by a meek attitude and a pale skirt and blouse. She walked for days. There was very little water. Gradually, her fellows dropped away, as did the formality of the checkpoints. The sky pressed down on her, a sickly animal, weakened and dim in the smoke. A sideways pallor glowed even in the middle of the day, the sun hanging in it like a button or a plate, no rays or shine to speak of.

The fence rose from the dirt, black metal, razors running like a split braid, a far-off mirage and then all the afternoon closer, until finally, she could reach out and touch the flawless metal lengths. She wrapped her hands around the bars, let her forehead sink into the space between them, small enough that not even a child could pass. She turned, to look at what she had come from, and found an empty stretch of desert disappearing into smoke.

It was not such a terrible end, she thought. Her throat could make no sound, and her fingers cracked at their tips, blackened fissures where her edges were splitting. She reached through the fence, cupped her hand across the dust that covered the hardpack, and brought a handful into the bowl of her skirt. Not such a terrible end at all.

Efleda woke to a wind across her face. She felt the fence at her back, the dust in her hand.

“Ma’am,” a voice said.

Efleda opened her eyes, and with great difficulty, stood. Beyond the fence, a hulking Suburban sat parked against the gloom. Two men stood just out of reach, both in working clothes, canvas jackets of a nothing color.

“Hello,” she said.

“Hello,” said the taller of the two men. “Purpose?”

“What?” Efleda said.

“What is your purpose?” the man repeated.

He spoke, and moved, like what held him up behind his skin wasn’t human at all but something mechanical, regimented.

“I’m going home,” Efleda said. Her tongue stuck in her mouth, a dry rasp as it pushed against her palate.

“Yes,” the taller man said, “but for what purpose?”

Efleda thought.

“To see my parents,” she said, a good bet for what might qualify her.

“All personnel not already evacuated are scheduled to be removed by month’s end,” said the shorter man. He spoke like a script, as if a ticker tape scrolled behind his eyes. “If you are among those with relatives inside the area, the quarantine center will notify you.”

Efleda crossed her arms. She shifted foot to foot, an eye on the tilting horizon.

“I do not have a stated purpose,” she said, finally.

The tall man produced a folder from his jacket, scanned a page.

“You are eligible to be a figurehead,” he said.

“Do you accept?” the shorter man asked.

“What’s a figurehead?” Efleda asked.

“Do you accept?” the shorter man asked.

Efleda clutched the fence. A figurehead, what she knew of it, was empty, either a puppet to be played with, or the carved buttress of a ship that cut its prow across the ocean. She thought of it, thought too of screaming, of hurling her body at the steel, of falling after, imprinted, to the dirt.

And what of the plans for that body? What of the blueprint, her mother? Was the woman old now, or even dead? Efleda imagined her, in that final place, the ruin of her cupped in padded silk and burnished mahogany, the box shut with a filigreed latch and lowered, certainly, into dark, wetted dirt. All around, the earth would crawl with life, and sealed from it, what was left of her mother would rot into the silken folds. It was what they would do should they find her, should she be delivered back to them. Anything, to be different than that death.

“Do you accept?” the shorter man asked, for the third time.

“Yes,” Efleda said.

And a section of fence trundled open, and the tall man caught her as she fell.

The windows were gray around her, a different gray, and the back door of the Suburban was rising, a wash of cold air across her face. She lay on a cargo platform, a wool blanket over her, her back against a single caseless pillow. The fog hung heavy, and she could hear the waves, not far at all, the persistent drone of them against a cliff. She moved to right herself, and found her hands zipped together with a plastic cord.

“Sorry,” the taller man said. “Protocol, you know.”

She blinked. The men stood back, speaking softly to each other. Efleda moved by inches, careful with herself.

“Efleda?” a voice said.

She sat up.

“Effie honey?”

And they appeared in the frame.

They were older, much older, her mother hunched and leaning on a golden-handled cane, her father’s hair gone, his belly flapped over the waist of his pants. Her mother cried a little, a beautiful, steady hitch. Despite herself, Efleda felt a rise, a pull toward the sound of the woman’s voice. She held out her hands to the men, turned her wrists up, for the ties to be cut.

“No, Effie,” her mother said, and shook her head.

“Protocol,” the tall man said, softer this time.

He produced a set of papers for her parents to sign, which they did, her mother with a brave and suffering smile, the effort she spent to keep it apparent for all to see.

Overhead, the trees stretched like a wet, vaulted roof. Efleda opened her mouth, and closed it again.

“Miss,” the tall man said.

And she felt their hands on either side of her, turning her toward the ocean.

The rock was like no rock she’d seen, and yet it stirred something long forgotten, an imprint from the shadows. It was at once run through with lines and also pocked, caves and hollows in a gridded lace. As if she’d asked something aloud, although she had not, the tall man leaned down and swept his hand over all they could see, and Efleda followed it, the mottled cliffside disappearing only at the end of the horizon.

A narrow path cut toward a small, jutted place that met the waves, the way dotted with impossible blooms of plump green plants. At the end of the bluff, the men lifted Efleda’s wrists, clapped shut a pair of rusting shackles embedded in the rock behind her. To her right, over a wide inlet of rough sea, she could see her parents standing, watching. She understood somehow that this was required, that they had to watch, that in it transpired some necessary permission. Even the shackles, she knew, were something of an overture. An anchor expanded, deep in her chest, a molten bloom that weighed her where she stood.

The men stepped back. The taller man patted her shoulder with a raw, pink hand. They turned their backs and plodded up the narrow path. Efleda was alone.

For a time, a single pilgrimage was still permitted through California, and it was by this that people came to know the Lady of the Point, and her wasting. They arrived by the seasons, brought flowers, crosses, cards to lay at the entrance to her path. They could not put them at her feet, so fierce always was the weather, but watched instead from a neighboring cliff as the Lady took the pounding surf. In spring, she was beautiful, and the crowds were thick. By late summer, they began to dwindle, and in fall, few stayed for what came next. The Lady withered, her skin etching gently down to muscle, her hair bleaching the color of the clinging plants, a fine pale gray in the rare November sun. Like the wooden busts on the old ships, breast thrust forward to the cannon fire, the Lady met what came. By December, the cliffside shrouded in decay, no one could stomach her wretchedness, their maiden a curdled thing, skin cragged and muscle in bright ropes across the sandstone behind her.

On the first of each year, a holiday crowd would gather to see their Lady anew, regrown in a single night, even her skirt and blouse the same fine linen as the day she first arrived. So it cycled.

What people did not know, what they would never discover, was that no two seasons were the same. In repetition, something was happening that no one had intended, a gradual shift. Left to the elements, bestowed with a life unnaturally long, the Lady of the Point was learning.

A little more each year she worked herself into the rock, and the rock, having long wanted of a kindly human touch, and having been left long deprived in the waning days of the Californians, worked itself back over the Lady. Each January, she emerged a little less, and each December, she embedded herself a little deeper into the cliffside. Decades passed. Pilgrimages thinned. Chaparral turned to ash, and the limbs of the oaks fell from their trunks in bursts of continuous ember. The sky, smoked orange, stretched its obscuring season longer with each passing year, and soon, there was no real sun to speak of. Governments closed. Ports were left abandoned. The last people of the Golden State, even those who had stood watch to keep its boundary, fled inland. There was no need to tell people they could not come to California anymore.

For centuries, the Lady remained, bearing down on the bargain she had made.

The mushrooms were first to return. After all that ash, and years of a true, rainless drought, the storms that finally dotted the coast drew the fungi up by the millions, fruiting bodies crowding to the surface. Next came the ferns, and after them the impossible, serotinous cone, its seeds still viable under layers of blackened sediment, the electric green sprouts of the redwood bursting up to meet a white, clear sun.

Should some errant wanderer, now generations gone and knowing nothing of the place he came to, risk himself to make the coast, he would find not the outcropping of grit and stone, and not the cold-soaked cliff cut with delicate holes. Neither, though, would he find the Lady.

Instead, the continent ended in a new miracle, a swelling, breathing cliffside, warm to the touch and slick, like the skin of something living, for that is what it was. For miles she stretched, the beating heart audible only on those mornings with the flattest of seas. If the wanderer watched closely, best from a faraway vantage, he might observe that, to every slapping wave that came, a warm pulse answered, a bulge from beneath what had once been rock, what he understood was rock no longer, but something else, bigger than any animal the world had ever seen.

Efleda? He did not know that name. No one did. He knew only an outcropping that met the wide and violent sea, a place for the first of the new Californians to settle, where it was impossible to forget the land was living.•

Kailyn McCord writes on the North Coast of California, with recent support from the Ucross Foundation and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. You can find her work at Literary Hub, Ploughshares, and The Masters Review, with more at her website. She’s on Instagram @kkmcwhere. When not writing, she likes to be outside.