I was eight when my father brought home the long piece of butcher paper. I sat on the kitchen floor with my crayons. He laid it out, put a mixing bowl on one end and a soup pot on the other end, and measured the paper with his magic metal tape. Ten feet! he said. Then he held out the tape to me and I touched the button and the metal slithered back inside, like a snake’s tongue returning to his mouth. The year before, there had been a rattlesnake in the yard behind the metal shed where my father kept his tools—he cut off the head with a machete attached to a hoe. The thing he used to get avocados off the tree. He taught me to catch them in a wash basket lined with a blanket. Fuertes, he always said. Better than Hass any day. Long and smooth skinned, like big green teardrops on the dusty tree.

My mother stood in the doorway between the kitchen and the hallway. My father was leaving for work. The sun had gone down. It was summer, and he left when the night sky was purple. Ten feet. All yours. Your pictures, whatever you draw, that’s gonna be 10 feet of art. No one else can draw a single damn thing on there. Not even one flower. Then he left for work at Stater Bros. market. He turned around like every night, one hand on the doorknob, and said to my mother, “What do you want, Terry?” and my mother said, “I never want another piece of meat in my life. Never. Not a roast or steak or even one stupid rib. I want to eat dessert three times a day, OK?”

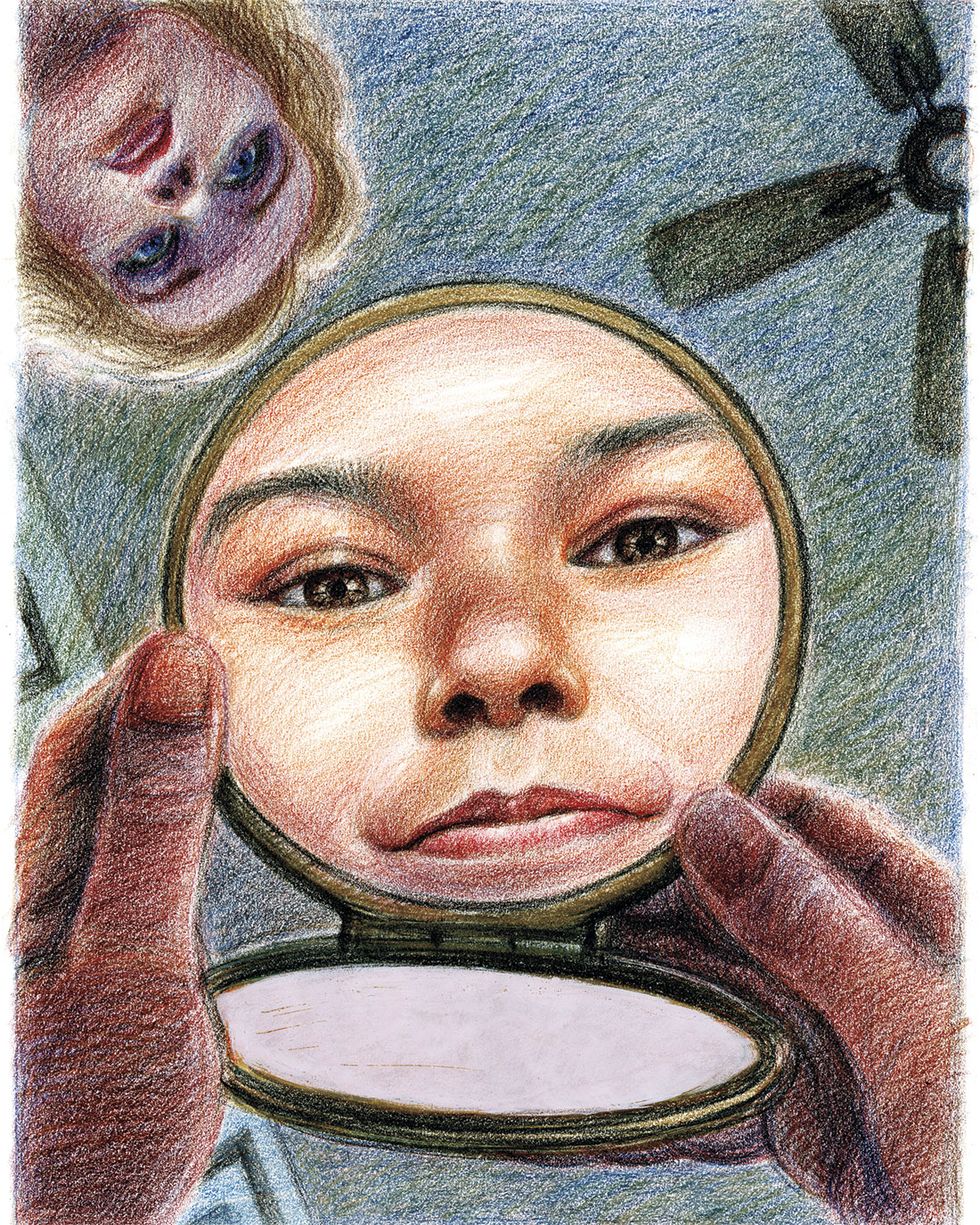

I remember that night. I drew pies with the cuts in them like feathers. Inside the slits you could see purple for boysenberry, red for cherry, but I had no gold for apple. I drew an ice cream sundae with a cherry on top, but the red crayon was dull. Not shiny. Maraschino, my father always said. That’s from Dalmatia, same place where the fire dogs first come from. My mother was in her bedroom. Her purse was on the table. I found red nail polish. The perfect cherry. For pistachio ice cream, the best green was the one eye shadow in the little black pot, and for the strawberry there was blush in the compact with the mirror. I remember that night. I lay on my back when I was done, looking in the mirror. It was the first time I saw my own eyes. Brown with little spokes of black inside like wagon wheels. My mother’s eyes were blue with specks of yellow like cornflakes. Then my mother came out of her bedroom, wearing her robe. I remember that she bit her lips so hard they disappeared into her mouth, and then she shook her head. She said, “Angie. You had to use the Lancôme. The best I had. Not the CoverGirl.”

“It’s a triple scoop. Like at Dairy Queen.” I know I rolled the compact across the wooden floor, and it stopped like a wheel at the wall.

“But I can’t eat any of this.” My mother put everything back into her purse, stooped to get the compact from the floor, and zipped the purse shut. She wiped her eyes, and I knew she was done crying. I froze on my back, imagining I was a fig beetle stranded on the sidewalk, waiting to see how angry my mother was. I imagined my belly iridescent and green under my T-shirt. I still have the T-shirt I wore that night. Pioneer Pirates. From second grade. The principal said Pirates were too violent. So now it was Pioneer Panthers. My father said, Pioneers killed everything they didn’t like. And Panthers? That’s not violent? Jesus, they’re idiots at that school. You better keep that shirt. I was a Pirate.

My mother said, Five-mile radius. Your whole life. Jesus is right. Jesus would tell you to take better care of your family. There’s nothing wrong with money.

That night, my mother did what she always did when she was tired of me and my father. She turned on the TV. My mother TiVoed all the services from Crystal Cathedral. My father knew she was obsessed with the Crystal Cathedral, but he didn’t know that when he worked a double shift on Sundays, because that’s when everyone bought their meat, my mother had been taking me to church and then out to a fancy restaurant named Benihana, with Carter Pierce.

My mother started to sing along, under her breath. The forks clinked in the metal sink. Had hail once hit the roof at Crystal Cathedral—a gray day? A softer tapping. The church was all glass, and we had been there six times. Five sunny Sundays. One cloudy Sunday where water or ice tapped at the glass.

I was 10 when my father told me he thought my mother would leave. He waited until she was gone to the mall. She worked at the Clinique counter then, at Nordstrom in Fashion Island.

Our house was small, two bedrooms, kitchen and dining room, and then the little archway into the living room at the front. There were four long windows in the living room. It was September. We were sitting on the floor playing Chinese checkers. It had been 105 for three days in a row, and the air conditioner was humming so loud the whole house shook. My father said, “July and August, it’s OK to be hot. But by September, the earth is tired, man. No dew. Everything feels worse. You gotta give your mom a break.”

“She has plenty of breaks.” I’d seen Fashion Island. It was huge. One day, my mother had taken me to work with her, because I had a fever. I sat on all the benches near Nordstrom, and the air was freezing, smelling of coffee, chocolate, perfume, and, somehow, leather from the shoes.

Three shadows darted on the wooden floor beside the metal checkerboard. Lizards. I had never seen them climb the window screens, hanging upside down. The fringe of their toes. Blue throats. Checked sides like the coat my mother loved. Creamy undersides, shiny as concealer.

“They can feel the AC on their bellies,” my father said. “First time I ever seen that, and you know I been here all my 35 years. Used to be nothing out here but citrus and chickens. Now all the sidewalks and streets make it hotter. Look at those dudes!”

Western lizards, they were called. They navigated the screens all afternoon, and finally they ran down the last time and disappeared. My father said, “Looks to me like she’s going to move to Newport, Angie. But it’s not you she’s leaving, OK? It’s me.” He turned on the Dodgers and went into the kitchen. He got out a package of meat. Too hot for the stove. He’d go outside and grill tri-tip. His favorite. He loved it cold for two days after that, sliced it pink and sprinkled it with salt.

“You sound like a bad TV show.” I got out my homework.

“There aren’t any good TV shows,” he said. “Just sports.”

I heard her on the phone the next day. What she was really leaving was the house. “It’s not even Spanish colonial,” my mother said to someone. “It’s more like San Bernardino prison.”

I waited until she hung up. It wasn’t Carter. Probably someone from work. Her voice was different when he called. I said, “We live in Rialto. San Bernardino is two blocks east. Dad says that all the time.” Our house was the last on the block, and my father always told me we had an entire acre. Only the front square was grass. The back, past his garage and shed, was all wild oats green in spring, gold in summer, and the avocado and orange trees.

She told my father that night she was going to live in Newport Beach with Carter Pierce, and that I would spend Saturday and Sundays there. I was in bed. It was Monday, my father’s night off. She said, “You know, he doesn’t sell pork chops and steaks. He sells houses. Giant houses with kitchens bigger than this whole place. Pools. Not sheds.”

“Then why does he want you? He needs moisturizer?”

“He says I’m more valuable than you’ll ever figure out. Because all you know is $4.29 a pound and whatever.”

“Slick. Very slick.” I heard my father open a beer. “What about Angie?”

“He says the house isn’t childproof yet and we have to get it ready for her.”

“She’s 10! I mean, shit, I don’t want her there anyway. I want her here. But what the hell does he have to childproof? She doesn’t need a baby gate on the stairs.”

My mother said, “He has thousands of dollars’ worth of art. Vases and statues.”

“She’s gonna tackle a fucking statue?”

“You’re cursing. That’s why you can’t handle church.”

“Crystal Cathedral isn’t church. It’s something else. Look at how you got what you wanted.”

“Church is about what you want—for your soul and your life and your—”

That was the first time I heard my father’s voice go low and—silver. Like a knife. “Fucking shut up. Fucking shut the fuck up. Sing that fucking song somewhere else.”

She did. She took one suitcase, because I heard the wheels on the wooden floor. She left me a card with roses and angels. She had written: Angela, my love, I can’t wait to see you on Saturday and Sunday. Those will be our special days. I will always come to school if you need me. I am putting together your new bedroom in our new house. I found a beautiful comforter set at Macy’s. Love, Mom.

When I was 12, and had to get my first bras, my father took me to Target, pointed to the Women’s sign, and told me to ask a woman for help. He went to the housewares section so he could make fun of the knives.

I couldn’t find a salesperson. There was only a young guy in that section, putting together a silver clothes rack. I panicked and grabbed five bras all in different sizes and went to the fitting room and an older woman looked bored and handed me a plastic tag for the door—five items. That lady was wearing a Target shirt and her chest was like a bookshelf halfway down to her stomach.

I shut the door and took off my tank top and tried on the bras like my friend Marisol said—hook them in front and then turn the whole thing around and pull it up over your boobs—but everything got twisted so I just picked two of the smallest—32A—and left the rest on the bench and then walked fast out of the dressing room and left the five on the counter where the woman was gone. My father was wandering around at the edge of Women’s like he wasn’t a pervert. When we left, I looked at the vases in the Home Décor section and thought it would be funny to buy one for my mother and Carter.

I had been to their house seven times. Saturday nights. Mostly they were gone, and my mother would call on Thursday night to say they were going out of town, and she would see me next weekend. But the seven times I’d slept there, in the white bedroom with the lavender comforter and shams, I kept seeing the statues. It was a great room, my mother said, all marble floor and black marble shelves in the walls and white figures inside them. Niches. Vases on all the tables.

“It’s leased,” my father said to her one night when she came to pick me up. “Not hard to have Mikey D. look that up.” Mikey D. was a deputy sheriff. He bought meat from my dad every other day. “Carter Pierce. Real name Timothy MacDonald. That means Son of Donald. Little Timmy born in Madison County, Iowa. Became a real estate broker in 2010. Leased home in 2012.”

But my mother just laughed. She was driving a new car. A Lexus. “Everything is leased. This car is leased, Bobby. Everyone else reinvents theirself and makes a new life. Just not you. Or apparently anybody else from here.” My mother was Teresa, and I was Angela, in Newport Beach. She wore dresses with geometric patterns, and heels. Her eyebrows were perfect. She wore only Lancôme makeup, and her perfume was Chanel, which smelled to me like pale green.

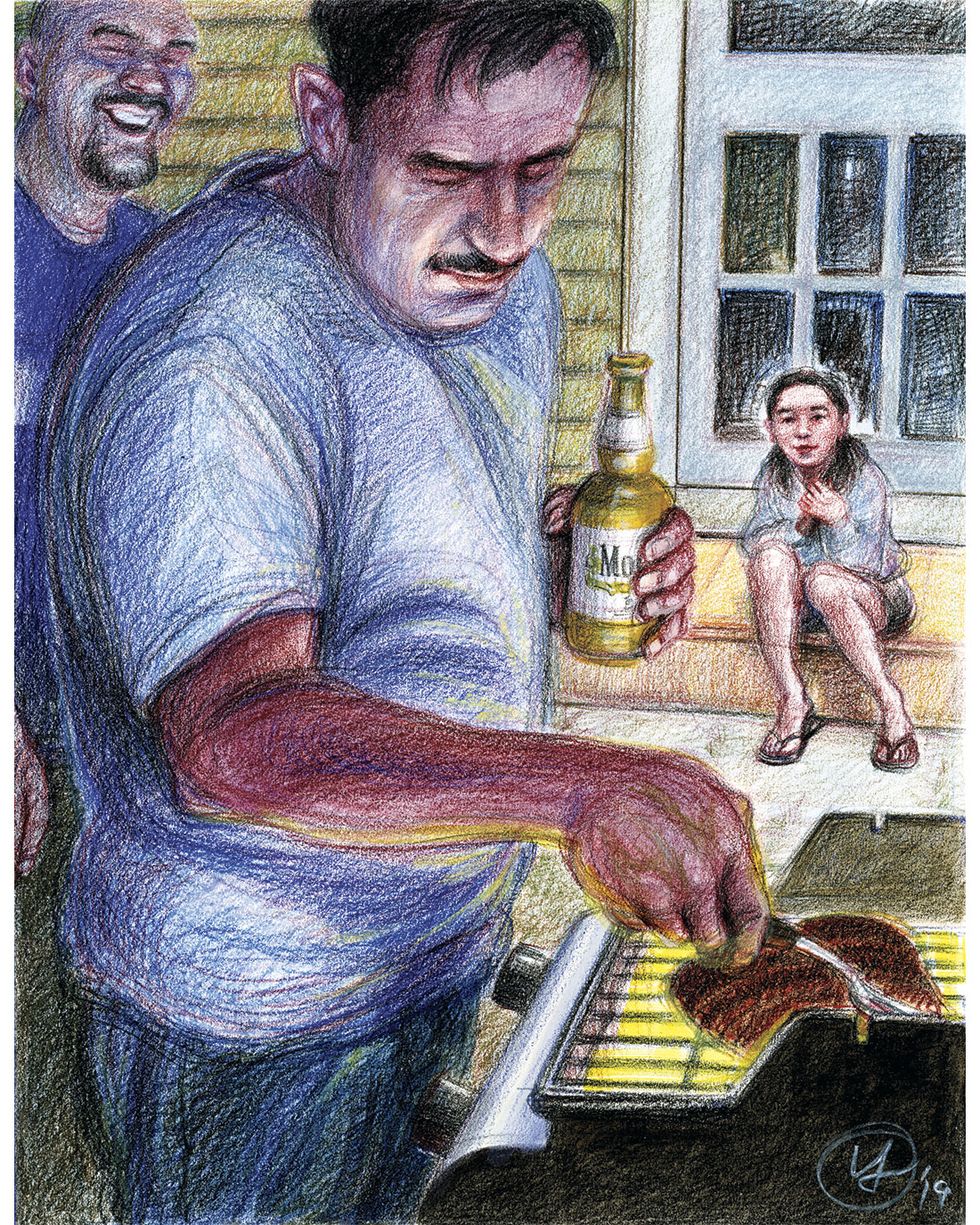

One night my father drank a lot of Modelo, and grilled a lot of tri-tip, with his friend Grief. Grief was an animal control officer, and he lived a few blocks away. He’d been buying ribs, steaks, and hot links from my father at the butcher counter since they were both 18, he always said. When his wife died, my father made a whole roasted rack of lamb, and took it to their house.

They both made fun of Carter Pierce. “I love these white dudes named Tanner. Hunter. Miller. Carter. Like that makes them sound rich. Those are just trade titles, man. We had this discussion before, Bobby Wright Jr.”

My father laughed. “I know. My grandpa the wheelwright. On the fucking wagon coming out here to California. Probably 10 years after your grandpa.”

I sat on the porch steps watching them. They played football together in high school. My father with his hands big as frying pans, from cutting all those bones and cartilage and tree branches. Grief with his curly hair in a long braid down his back, and his mustache black and straight around his mouth, so I always wondered how hair could be different coming from the same skull. I had been to Crystal Cathedral the week before, and I saw all the bald heads in the rows. Men and boys—you could see their lives and their genes and their ages in their heads. Big folds of skull-skin at the back, on some guys. Their heads scarred from getting hit or even from bug bites. We were in church forever.

I knew I would never leave my father. I would never move to Newport Beach. I had Coke in a bottle. My father and his friend were laughing. My father said, “I don’t give a shit what fucking computers they invent or what houses they build. Everybody has to eat meat and the only way to get a steak is for me to cut up a fucking cow and wrap the pieces in butcher paper. Every damn day. I see their eyes when I’m wrapping up that carne asada or that roast and they think I’m a fucking god. This one lady cried the first time she came in. She was from Sudan. Like her husband was one of those Lost Boys. She watched me put this rack of lamb together and she started crying.”

He looked over at me. I knew it wouldn’t make my life easier. He’d be scared of the Women’s section his whole life. People always say a butcher will cut off a finger. But when I was 16, he taught me to drive, and he was still so nervous by the time he got to work, he cut off part of the soft edge of his left hand, below the little finger. A wedge of palm. The scar pulled his fingers into a claw.

When I was 20, a sophomore in college, my father died in the freezer at the store, on a Sunday morning. It was September, 109 degrees that day, and he’d gone from the hot truck to the cold of the butcher area, put on his sweatshirt with the hood up, and fell on the cement floor. I knew the names of the women in his head who would be coming to see him—Mrs. Esquivel, Mrs. Trujillo, Mrs. deFrance, Grief’s sister-in-law Rosie. The women he loved after my mother left us.

Susan Straight’s latest novel, Mecca, was a finalist for a 2022 Kirkus Prize. This story is adapted from Black Star Canyon, a novel in progress that picks up three weeks after Mecca ends.