Danielle Bergstrom couldn’t stay away from Fresno. She had lived and worked there as a city planner after college before enrolling at Cornell University to pursue a master’s in regional planning. After earning her degree, even as the city and its pressing inequities kept a grip on her imagination, the 25-year-old landed a job with the Oakland-based social justice nonprofit PolicyLink. For the next three-plus years, she crisscrossed the country—analyzing the community impact of a new light-rail line in Minnesota’s Twin Cities, lobbying Capitol Hill for better housing protections for low-income renters, jetting from Seattle to Providence to Detroit. But the whole time, Fresno, a city often derided as the “armpit of California,” was never far from her mind.

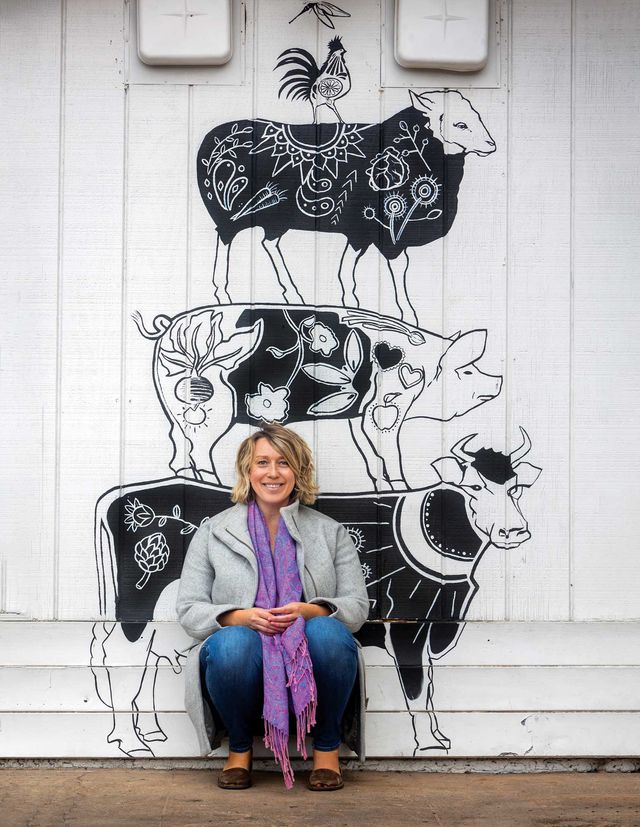

During grad school, she says, “everyone who knew me was like, ‘Oh my gosh, you can’t stop talking about Fresno.’ ” She tells me this over Zoom from her house in the Fresno High neighborhood. She sits next to a window, her light blond hair slightly tousled, her chin resting between her index finger and thumb. Outside, it’s one of those pounding-hot days in the Central Valley when the horizon seems to shimmer.

Danielle Bergstrom joins Alta Live.

WATCH

She remembers when she realized she had to return south, a perhaps inexplicable decision at the time but perfectly logical in hindsight. “I remember sitting in a restaurant in Portland, Maine, one night, and I thought, ‘I should be in Fresno,’ ” she says. “It was an aha moment.”

She convinced her bosses at PolicyLink to let her move back to Fresno and work remotely, then in 2014 she returned to city government and policy work there. Dissatisfied with the pace of change, though, Bergstrom developed an itch to get out on her own: “What kept percolating through my mind is, How do we do a think tank, meaning original research on local policy issues, that makes it super accessible for the average person?” Four years after returning to Fresno, the planner and social equity advocate founded Fresnoland, a nonprofit media and policy lab focused on local government as well as local water, housing, and land-use issues.

This article appears in the Winter 2022 issue of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

Put on the map in 1872 by the construction of a Central Pacific Railroad station, Fresno and its eponymous county grew to become the nation’s agricultural epicenter, producing almonds, pistachios, grapes for raisins, and many other crops as well as livestock. California’s—and the United States’—tortured history with immigrant populations further complicates the Fresno region’s standing: the state’s Foreign Miners’ Tax, first passed in 1850, was a $20 monthly levy that targeted Mexican and Chinese immigrants drawn by the gold rush; Chinese immigrants, who sought financial opportunities like building the nation’s railroads, were banned outright by the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882; and during the urban and suburban development of the 1950s and ’60s, those living closer to the agricultural fields, who were disproportionately people of color, were left to fend for themselves in unincorporated areas, without regulated municipal services like clean water.

Despite this difficult past, California’s fifth-largest city is growing, even as the state recorded its first-ever year-over-year drop in population in 2020: California lost 182,000 residents, while Fresno added 3,319 people. Over the past four years, the city has witnessed the nation’s highest average increase in monthly rent, reflecting a booming housing market and pandemic-enabled remote work.

Such changes have sharpened many of the city’s long-standing inequities. Bergstrom, who was raised in nearby Kingsburg, recalls that the majority of her classmates were children of migrant farmworkers. “At a really young age, I was confronted with income inequality and how stark that is,” she says.

Bergstrom remembers flipping through an issue of House Beautiful in the summer after her sophomore year at college and coming across a profile of longtime Charleston, South Carolina, mayor Joseph Riley Jr. She was blown away by his revitalization of the city’s poor neighborhoods and quickly added a minor in city and regional planning to her biology major.

Before launching Fresnoland, Bergstrom spoke with friends and colleagues about various means to address local social inequities. She concluded that a powerful way to deliver information to the people who needed it most was via news reporting. Pregnant with her daughter at the time, she asked for a meeting with the Fresno Bee’s editor, Joseph Kieta.

“I’m waddling into his office, and I must have just looked like a crazy person, because I said, ‘Hi, I’m Dani, I have this political background—no journalism experience—but I have this really great idea, and I’m going to write a series of stories for your paper about where our water’s coming from,’ ” she recounts.

“OK,” he replied. And with that, Fresnoland began to take shape.

A year and a half later, Bergstrom had raised enough money from foundations and individual donors to pay herself and a staff of one editor and two reporters and had established a partnership to provide investigative pieces for the Bee, which had lost its water and environment reporter.

Fresnoland is part of a movement in which nonprofit newsrooms are replacing or complementing local newspapers. Between 2018 and 2020, some 300 newspapers closed nationwide. In roughly the same period, when media conglomerates and hedge funds gobbled up many of the remaining papers, some four dozen nonprofit groups like Fresnoland were formed to reinvigorate community-based news.

Since debuting in the Bee in 2020, Fresnoland has published an exposé of racist land-use practices that led to water pollution in primarily Latino areas of the San Joaquin Valley, a history of the segregation of the local Black community, and an investigation of a Fresno slumlord, to name just a few of its pieces. Fresnoland stories are written and edited by staff, with additional editing by the Bee.

Crowdsourcing—which lets anyone contribute to news gathering—is central to Fresnoland’s ethos. The organization uses social media for tips and information; it even trains and pays residents to attend public meetings and posts their notes online. The nonprofit newsroom offers an elixir whereby community engagement can lead to the kind of change Bergstrom once sought solely through policy work.

And so it’s somehow fitting—and not wholly unexpected—that Bergstrom’s commitment to Fresno manifests itself through journalism. After all, it was an issue of House Beautiful that started her on this path.•

Brad Balukjian is a biology professor at Merritt College in Oakland and a freelance writer. His first book, The Wax Pack, was named one of NPR’s Best Books of 2020.