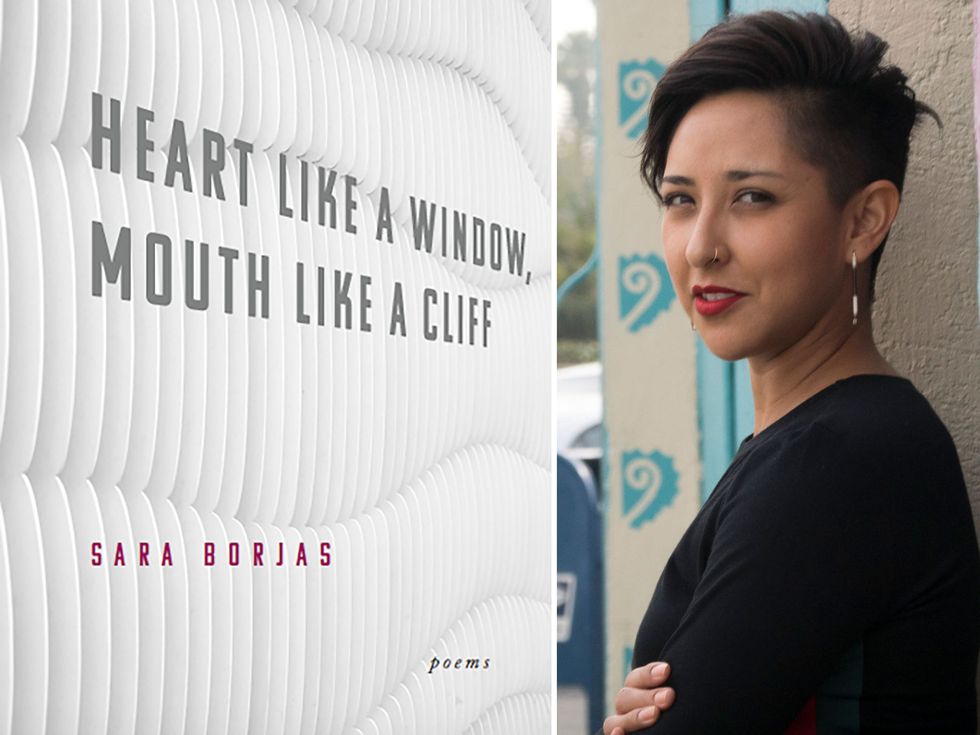

Sara Borjas’s work is confrontational. It isn’t poetry for anyone’s comfort, least of all the speaker of her poems. Heart Like a Window, Mouth Like a Cliff challenges Borjas’s ideas about identity and the dynamics of family, thereby asking readers to examine their own biases and assumptions. The poet’s words describe a raw and affectionate love, a heart often broken by its own intensity. Heart Like a Window both celebrates and laments its speaker’s identity. Borjas’s poetry relies on intimate descriptions and the exploration of taboos to explore how family and community can break down, and what it can mean to love something despite its imperfection. This is work that inhabits the liminal space between loving and resenting our roots.

“My mother / would rather cut off her hands than hit me,” Borjas writes in “I Know the Name of the Desert.” “She would rather / swallow boxed chardonnay, open her throat like a rusty silo for rain, / light a candle for a girl she knows, and turn this evening / into a watermelon sliced, a rest stop where she is allowed to play.” Her parents are often the subject of her poems; her mother’s drinking and her own rebellion against the silence on sensitive matters preferred by her family are common topics. Borjas’s feelings about her hometown of Fresno, her Latinx heritage, and their roles in her present life are central to how she explores her family dynamic. In “My Father Imagines Winning the Lotto,” she writes, “Never forget / where you come from, my father told me as a little girl, scared / I might pull up the ladder behind me.” In “We Are Too Big for This House,” she writes, “I think my family is afraid of memories. And I think they are afraid of me sometimes because I use memories in arguments. They think I am a monster.” There is guilt at the heart of her work, but also wild affection.

Alta caught up with Borjas recently via email to discuss what drives her work and the way she hopes poetry will move forward from the present moment.

EXCERPT FROM “WHAT I KNOW ABOUT FRESNO”:

/ 2 /

teaching the farmers

minds and the workers hands how to handle

their laws and their skin, how to fear

their absence which is the same as love’s

eyes closed. I know the silt left dry

at the bottom of an irrigation ditch

/ 9 /

which is sometimes

the same thing as pride, which is sometimes

the same thing as devotion. I know I will die here.

I know the chain link around the water pump,

the electrical poles like thousands of crosses

/ 4 /

like a single breath—

I know the oil trains going by like my own heart…

What central question does your work ask?

How do I decenter whiteness in my desires and begin to decolonize my life, starting with my love? I for real feel like each poem is a workshop where I try to recognize and unlearn what Audre Lorde calls “the oppressor that is planted deep within each of us.”

What, in other disciplines, inspires you to create?

Cooking. Food, when it is complete, is a total complex energy. A bite of something can communicate a life, or have a kind of duende, or dark energy that, like Lorca says, comes up from the earth through the soles of the feet. Vibes are official as hell, although academic or scholarly discourse might deny that in service of an intellectualism that truly does not serve our humanity, but rather, white supremacy. I also love watching documentaries and docuseries. They remind me to archive, and of the power in recording, because colonized people don’t have a choice of knowing or having clear answers or roots.

Do you listen to anything as you write?

If I do, it’s one song on repeat until it becomes no song and more like a net. A little atmosphere. It also helps me feel unalone. Right now it’s “Only Girl” by Kali Uchis and “I Had a Choice” by Sun.

What obsessions, coincidences, or connections made it into this book?

The obsessions that made it in were love, Danielle Steel, myth, and Fresno. The connections that I am certain made it are the relationship between alcoholism and preciousness and love and the relationship between loyalty and nation and family. These will be lifelong, I am sure. I don’t think I believe in coincidences.

What kind of poetry do you think will come out of this moment in history?

Hopefully, more poetry by white-identifying poets that acknowledges whiteness and their own racialization, and I am lighting a candle in hopes that it is poetry of participation rather than of witness. I hope representative space is urgently made for nonwhite, queer, trans BIPOC folx during this moment in history. With a publishing industry that is 89 percent white, though, folx would have to give up unearned seats to make space for editors whom these poems could truly resonate with and feel meaningful to without tokenism.

What’s on your to-be-read list?

I am mostly reading scholarship and articles and essays on anti-Black racism, white supremacy, and U.S. history by Black writers, artists, and academics. I am in a few different reading groups, and we are meeting weekly, and I am so, so, so grateful to everyone in them. On the creative writing front, I am about to get into Horsepower by Joy Priest, Borderland Apocrypha by Anthony Cody, All That Beauty by Fred Moten, White Flights by Jess Row, Bareback Nightfall by Joshua Escobar, Thrown in the Throat by Benjamin Garcia, and Defacing the Monument by Susan Briante.

Give us the elevator pitch for Heart Like a Window, Mouth Like a Cliff.

Your house is burning. You must change your life.

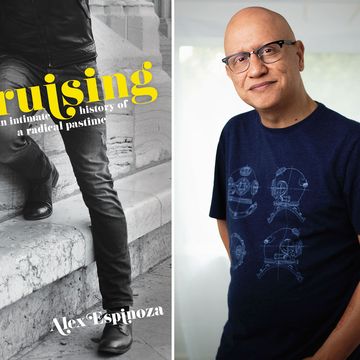

Heather Scott Partington is a writer, teacher, and book critic based in Elk Grove, California. She most recently interviewed Alex Espinoza for Alta Asks.

HEART LIKE A WINDOW, MOUTH LIKE A CLIFF

- By Sara Borjas

- Noemi Press, 95 pages, $15

Heather Scott Partington is a writer, teacher, and book critic. She is a regular contributor to Alta Journal. She is the winner of an emerging critic fellowship from the National Book Critics Circle and the Critic-in-Residence for UC Riverside’s Palm Desert MFA. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Washington Post, USA Today, The Los Angeles Times, and The Los Angeles Review of Books, among other publications. She lives in Elk Grove, California, with her husband and two kids.

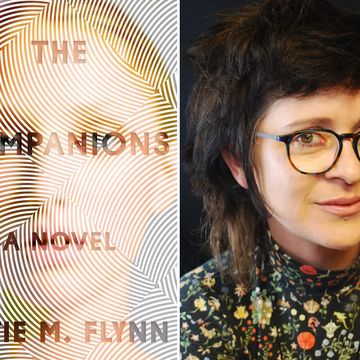

![ATA061020altaasks_img01 Tod Goldberg, author of Gangster Nation, is also a podcaster and a professor. He draws inspiration from “bingeing TV and reading poetry, [which] do the same thing to my brain,” he says.](https://hips.hearstapps.com/altaonline/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ATA061020altaasks_img01.jpg?crop=0.75xw:1xh;center,top&resize=360:*)