Film auteurs have long understood that a double allures and frightens in equal measure. Our fear of automatons, of dolls, of robots in human form is instinctive: here is this thing that looks like us, is able to behave as we do, but remains fundamentally mysterious and, for all we know, may be propelled by secret forces outside our control. Doubling might be literal in its manifestation: the character who looks like another character, the character who represents what another character lacks. At the same time, a double also serves as a potent symbol, a metaphor for our own fears about identity—or its loss.

Such anxieties drive Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, which considers a nurse who confides in her mute patient but struggles to differentiate herself. Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan explores the horror that arises when a young ballerina notices the uncanny similarity between herself and another member of the company, who dances with greater artistic abandon.

This review also appeared in the Monday Book Review Newsletter, sent to your inbox every week.

SIGN UP

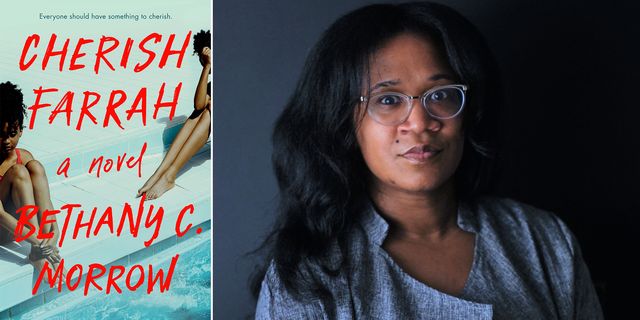

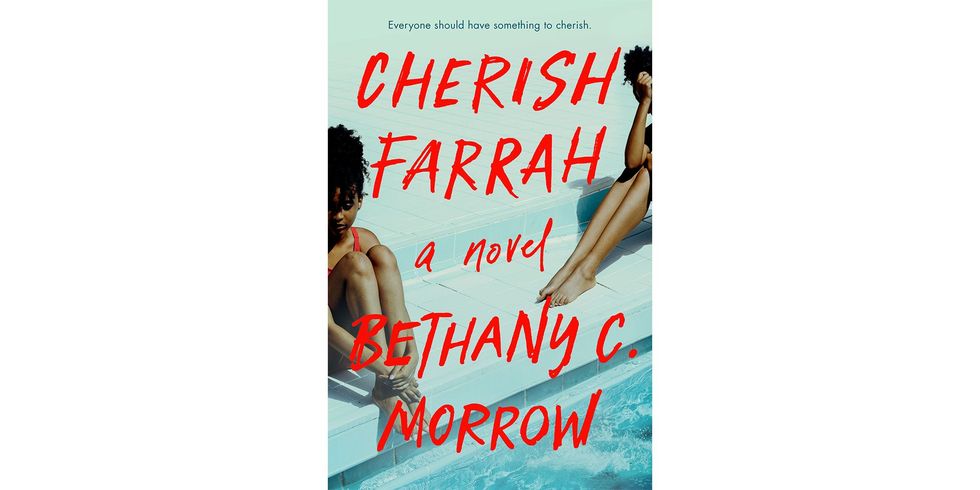

Bethany C. Morrow’s latest cinematic social-horror novel, Cherish Farrah, is right at home among these uneasy, atmospheric narratives, the hallucinatory effects of which are born of doubles.

The premise of Morrow’s novel is simple. A calculating teenager, Farrah, uses manipulation to secure an open-ended invitation to live with her best friend, Cherish, who was adopted as a young child by Brianne and Jerry Whitman, a rich, white progressive couple. The Whitmans congratulate themselves on the moral superiority of their decision because Cherish is Black. A similar sense of self-regard leads them to take Farrah in after her parents suffer financial ruin.

For their part, Farrah’s parents regard their daughter with suspicion. That’s unsettling, and yet, even in the first few pages of the novel, it doesn’t feel out of place. Here is doubleness through a mundane lens: two Black girls who face a related set of dilemmas but respond to them in distinct, even opposing, ways. Farrah’s disturbed scheming and cynicism counter Cherish’s gentle acquiescence and gullibility.

Farrah’s chillingly claustrophobic perspective infuses Cherish Farrah with a deep and creepy dread. She seeks control of every situation, every intimacy. To her, Cherish is Black in appearance only. Farrah believes that her friend’s parents have coddled her into acting white, a whiteness that has made her weak: “Because Cherish is still who she is. She’s white girl spoiled, but she isn’t white—which is why I can fill that void.… She is perfect, and she is mine.” Farrah regards other people, especially Cherish and her family, as puppets whose strings she can pull.

Is it teenage envy that motivates her? Sort of, since she values her own ability to handle other people—a trait she associates with race. Or is her connection to Cherish tinged with dark eroticism? Yes to this, too. Farrah is fluent in the vocabulary of on-screen heterosexual obsession, considering Cherish a “masterpiece” while also trying to manipulate the other girl into ceding all control to her. They play a deranged game in which one holds the other underwater; the one submerged is supposed to prove her trust by not fighting back. Yet more than desiring Cherish, Farrah wants to be her, to have the life of privilege she derides.

Farrah and Cherish are symbiotic, two sides of the same coin, the punishment of one accruing to the other’s benefit. If, in places, it appears that Farrah might be more victim than villain, at its best, the novel defines a tone, ratcheting up atmosphere and mood by way of symbolic gestures rather than specific turns of plot. Farrah adheres to a sick logic, but there are ruptures, dream sequences, including one in which she attacks Cherish’s boyfriend, who also seems to have a double—his own Cherish, as it were. Double of a double, mirrors of mirrors, turtles all the way down. A book within the book sets forth the precise racial dynamic we are witnessing: a melodrama that astutely treats whiteness not as a matter of skin color but as a state of psychological entitlement that depends on the scapegoating and punishment of Blackness in order to exist.

In her debut novel, Mem—a speculative history that also makes use of the uncanny power of multiples—Morrow intentionally omitted the reality of racism. She didn’t want, she acknowledges in an author’s note, to look at the ugliness of whether race would have hindered her protagonist’s entry into the social elite. Cherish Farrah’s race dynamics, by contrast, are a sparking power line, popping, cracking, eventually exploding.

Dread of loneliness can be eclipsed, it turns out, by the terror of not being able to tug oneself free from another. The submersion of self can feel, deceptively, like connection, but too much and we crave lines and separation again. We violently want ourselves back. Or, Cherish Farrah suggests—not.•

Anita Felicelli, Alta Journal’s California Book Club editor, is the author of the novel Chimerica and Love Songs for a Lost Continent, a short story collection.