Cyndy McCrossen has been a location scout in Albuquerque for nearly 15 years. Her portfolio of locations includes cattle ranches that can pass for Montana and a Victorian-filled neighborhood called Huning Highlands that can sub for Anytown, USA. “You erect a yurt village and put some riders on horses and hey, we’re in Mongolia,” she says. One of her biggest breaks came in 2009, when she began work on the AMC series Breaking Bad, which, along with its spin-off, Better Call Saul, became a long-lasting boon to the local economy. Even now, hardcore fans can grab a meth-themed Blue Sky doughnut at Rebel Donut or take a “star tour” of the city in an RV—“just like Walt and Jesse’s”—to check out the seedy motels and the fried chicken joint made famous by the show.

Not all that long ago, Breaking Bad would probably have been filmed in Southern California, and indeed, the show’s producers were hoping to set and shoot it in Riverside, given that the Inland Empire was then known as the world’s meth capital. But a generous tax credit in New Mexico pulled the entire production east.

Over the past couple of decades, tax credits have lured thousands of films and TV shows out of Southern California. Powerful financial incentives brought Good Will Hunting and The Handmaid’s Tale to Toronto, Black Panther and The Walking Dead to Georgia, and Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker and Fast & Furious 6 to the U.K. As these areas became film centers in their own right, talent and crew and even studios from Los Angeles resettled around the globe, and production companies and workforces also sprouted up locally.

This article appears in the Winter 2022 issue of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

There are few signs of letting up. In Albuquerque, Netflix is committing $1 billion to expand the company’s already extensive facilities there, which will include 10 new soundstages. In Georgia, the fiscal year ending September 2021 saw the state’s film industry set a record of $4 billion in direct spending, thanks in large part to an incentives program that handed out $870 million in subsidies in 2019—more than New York and California combined.

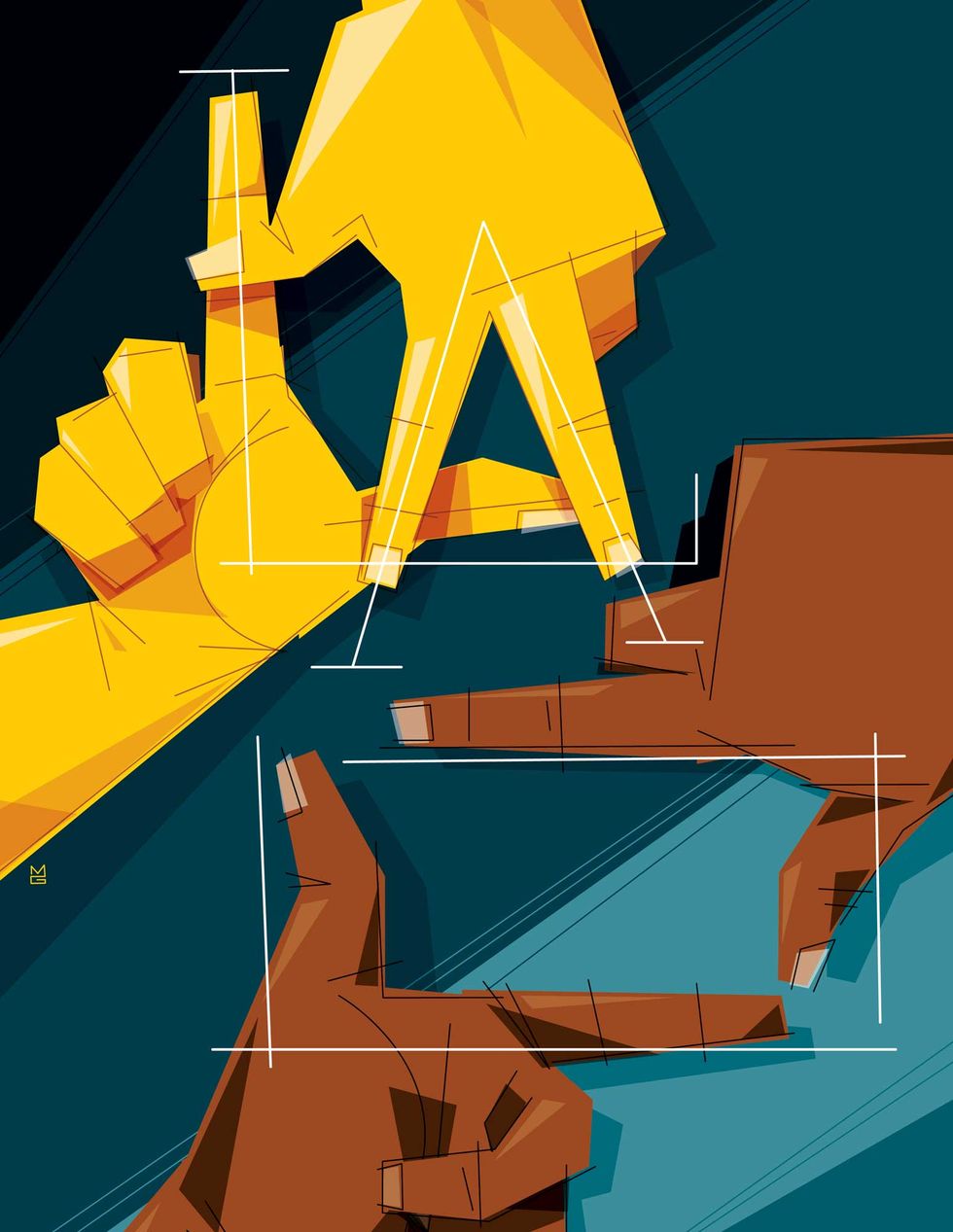

It’s clear that Southern California has lost out owing to runaway production: in 2019, the last time Hollywood had a full year of moviegoers in theater seats, only one of the 10 highest-grossing live-action films in the United States—Captain Marvel, at number 5—was shot primarily in Los Angeles. As a result, the region has launched the unlikeliest of efforts: an aggressive and spirited campaign to keep Hollywood in, well, Hollywood—a town synonymous with the film industry. But did tax breaks alone really put Hollywood in such a dire situation? And what can the industry do to lure these productions back?

BOOSTING THE BIZ

Paul Audley is not a film guy, or hasn’t been for much of his life. Now in his 60s, he’s been a police officer, an attorney, and the mayor of Fairfield, Connecticut. He is, in conversation, even-keeled, temperate, not given to hyperbole. Since 2008, Audley has served as the president of FilmLA, the film office of the City and County of Los Angeles, working to stem the tide of runaway production that began rising well before his term, in an industry battered even harder during the pandemic. “COVID,” he says, “has not been fun at all.”

During normal times, FilmLA’s job is to help filmmakers secure permits, smooth relations between film crews and the residents whose neighborhoods they commandeer for weeks or months, and conduct research on the “economic, civic, and cultural benefits” the industry provides to the region. Of late, Audley finds himself to be something more of a wartime general deploying all tactics necessary to get productions to stay in L.A. Among his most potent weapons are—no surprise—financial incentives. To counter the millions offered by places like Toronto and Georgia, Los Angeles has dramatically upped its tax credit game since Audley became president. In 2009, the state film commission launched a program offering $100 million in credits per year. Statewide incentives were increased to $330 million in 2015 and then expanded again by $180 million over two years in 2021; a new $150 million incentive program was also added to encourage infrastructure projects and workforce diversity.

Audley also has to contend with industry professionals in other countries spreading false rumors about how the unions in Los Angeles won’t let outside film companies work there—think On the Waterfront, but with grips. “I really discovered the pervasiveness of that rumor when I went to a conference in London five years ago,” Audley says. (A larger conversation about unions on film shoots was amplified last October when, on the New Mexico set of Rust, actor Alec Baldwin accidentally shot and killed the film’s cinematographer some seven hours after nonunion camera crew members were brought in because union members unhappy with working conditions walked out.)

Why should a production stay in L.A.? Audley’s pitch cites talented crews, the ease and speed of obtaining permits, and the area’s sprawling soundstages and back lots, many of which date to the dawn of the movie business. Los Angeles County is still the largest production center in the world, he says, with 5.3 million square feet of stage space.

The city’s main competitors, in Audley’s eyes, are New York and Vancouver (“they were really the first in this race to pull things out of L.A.”). Georgia is also “pretty substantial now,” he adds, as is the U.K. “Most of the major films by U.S. studios are being done in the U.K.,” he says. And then there are the places that tried and failed, like cinematic gold rush towns gone boom and bust. Some were done in by tax incentives offered by one governor and taken away by future lawmakers (here’s looking at you, West Virginia—the state ditched its tax credits in 2018 after discovering they had generated only 41 cents on the dollar); others didn’t have ready talent or infrastructure. “A lot of states were throwing out cash incentives without particularly strong planning and found they were losing their shirts in the process,” he says.

It’s a war on two fronts. Audley is selling Hollywood to Hollywood, hyping the economic benefits of the place to studios and streaming empires. But he’s also selling the business to everybody else who lives in L.A. “The industry isn’t just the six or seven major studios or 10 megastars; it’s the tens of thousands of people who work every day at good middle-class jobs and live in these neighborhoods,” he says. Film and digital media account for 6.1 percent of L.A. County’s jobs, with an average annual wage of $117,000, nearly double the average wage overall. “There’s a lot of reasons people like to stay here, in addition to the fact that they just like to stay home,” he says.

One recent advantage that L.A., and indeed all of California, has had over some areas of the country is its political climate. Early last year, Will Smith pulled a film production out of Georgia because of the state’s discriminatory new voting law; six months later, The Wire creator David Simon announced he wouldn’t film an upcoming HBO project in Texas owing to the recent passing of a law banning most abortions there.

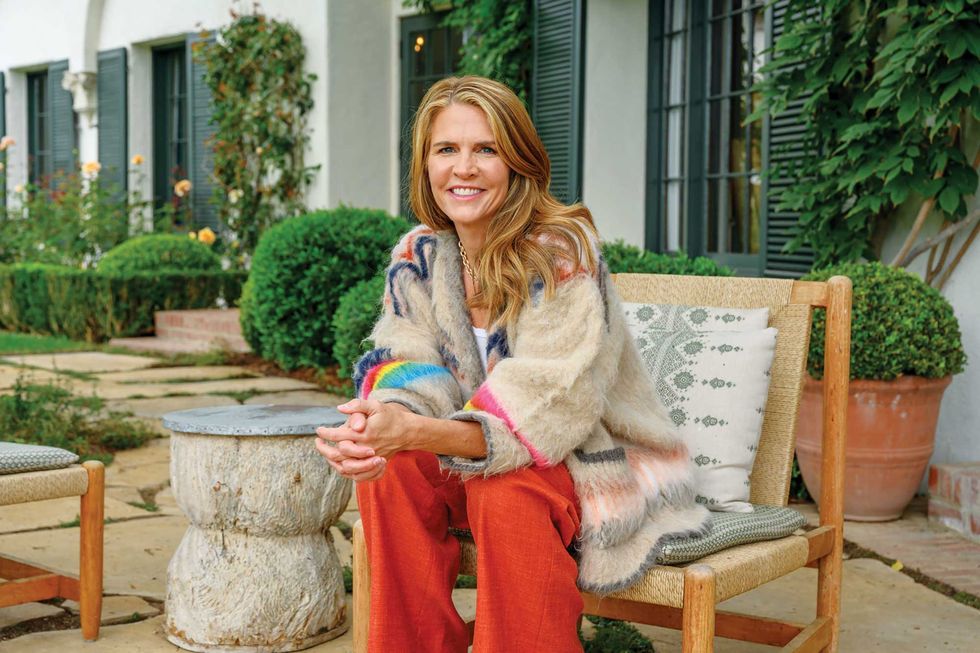

It’s an advantage not lost on Colleen Bell, the executive director of the California Film Commission, which oversees film and TV production throughout the state. “We’ve received quite a few inquiries from states where they started production and have decided for a number of reasons that they’d like to relocate to California,” she says. “And one of those reasons is that they feel that their values will be better aligned with the values of California.”

A former producer on The Bold and the Beautiful (and, for a spell, U.S. ambassador to Hungary), Bell took over at the commission in 2019. “I had been in the job seven months before the pandemic hit,” she says. Bell loves California. “We create magical moments for people and broadcast them all over the world,” she says. One of her favorite TV shows is the five-Kleenex drama This Is Us, which is filmed in California and is a beneficiary of the commission’s generous tax credit program.

In addition to administering its now $660 million in tax credits, the commission serves as the “mother ship” to nearly 60 regional film commissions peppered throughout the state. The commission’s website features a promotional short titled Film in California that celebrates the landscapes and cityscapes the state has to offer, from golden poppies to snowy mountaintops to the Golden Gate Bridge. “Anything you desire is here,” the narrator intones.

One of the commission’s classiest megaphones is a beautiful magazine called Location. Such actors as Matt Damon, Natalie Portman, and Tom Cruise have appeared in it, but the real stars are the featured filming locations, like Santa Clarita’s Agua Dulce Airpark (a private airport that was transformed into the grandstands of Le Mans for Ford v Ferrari) and San Diego’s Naval Air Station North Island (where 250 cast and crew members descended for the upcoming Top Gun: Maverick). Full-page ads for cities, counties, and studios beckon producer-readers to shoot there.

In certain ways, the combined efforts of Bell and Audley are working. By last summer, filming in the Los Angeles area had returned to pre-pandemic levels. But comparing past figures with present ones can be deceiving given that streaming subscriptions, driven by the pandemic, were on track to increase by more than 50 percent in 2020 (though that shutdown surge seems to have tapered off somewhat in 2021). That’s a lot of folks sitting at home watching a lot of new shows. And a lot of those shows are still not being made in L.A.

BLAME CANADA

Before COVID-19, copies of Location were distributed at awards shows and events like the Toronto International Film Festival, where Justin Cutler served as the director of the Industry Office. Nowadays, he heads the Ontario Film Commission, where, as it was at TIFF, his main job is to convince moviemakers to come north. And they do. Ontario already has nearly 4 million square feet of stage space, with plans to add another 2.5 million, spread between six facilities, before 2026. Recent projects filmed there include Suicide Squad, the Netflix series Schitt’s Creek, and The Shape of Water, which won the Oscar for Best Picture in 2018. Toronto has been a major filming site since at least the 1980s, when hits like Cocktail were shot there. “It’s one of the biggest industries in the province,” says Cutler.

Cutler sees the movement of productions from L.A. not as a zero-sum game but as a moment when the wealth of new streaming opportunities is lifting all boats. But for Bell and Audley, every movie filmed in another state or country is one that might have been made in L.A. or elsewhere in California; every new soundstage built by Netflix or HBO somewhere else represents x number of series that the state is missing out on.

So competition remains fierce between the biggest film-production centers, as studios expand and soundstages bloom in anticipation of a post-pandemic future in which the needs of the streaming giants continue to grow. As ever, one of the biggest selling points hyped by just about every film commission is how their town or region can mimic other towns or regions. Cutler cites Toronto’s ability to evoke European and midwestern locales, but admits that the area won’t host a lot of movies about skiing (“We’re not the most mountainous region in North America,” he says); McCrossen concedes that, while Albuquerque can sub for Mongolia in a pinch, her town has lost gigs to L.A. when producers have needed palm trees. “We don’t have grand ballrooms like L.A., or big train stations,” she adds.

Los Angeles, however, is a pretty talented actor itself. “L.A. has played virtually everywhere in the world,” Audley says. “Every one of the CSIs, whether it’s in Miami or New York or L.A., they were all filmed here.”

One issue that will soon become pressing—assuming that streaming keeps up its breakneck pace—is stage space. “We’ve been well over 90 percent occupied for several years now,” Audley says, with many of the stages booked by TV series that reserve spots year-round. Of course, if Netflix and Amazon had decided to expand in parts of Southern California instead of in Toronto or New Mexico or the U.K., maybe studio space wouldn’t be such an issue. But still, all those booked soundstages in town can’t be such a bad thing, right? “Oh no, it’s not!” says Audley. “It means the industry is thriving and wants to grow.”•

Robert Ito is a journalist based in Los Angeles. He writes about film, television, and theater for the New York Times.