At San Francisco’s nostalgia-inducing Swan Oyster Depot, the menu includes oysters from both coasts: you might choose among Kumamotos from Humboldt Bay, California; Miyagis from Puget Sound, Washington; Blue Points from Cape Cod, Massachusetts. But if you go to the restaurant, with its marble counter and 18 wooden stools, half of which date back to the 1800s, you might be able to try the favorite oyster of one of the restaurant owners. “If I had one oyster I could eat from anywhere in the world, it would be the Olympia. It’s a very unique oyster, with a very briny, very mineral-y, almost coppery taste,” says Steve Sancimino.

Sancimino loves to tell interested customers that the Olympia is San Francisco Bay’s native oyster and that the miners came and ate them all. Then, two of the biggest growers—John Stillwell Morgan and Michael Bolan Moraghan—cultivated them in places like Oyster Point, in South San Francisco, and the East Bay. But during the gold rush, the sludge from hydraulic mining came down from the rivers and smothered the oyster beds. “When they hear the story, people go crazy for them,” says Sancimino.

However, the history of the hometown oyster may be more about quiet resilience than boom and bust. When throngs of gold-seekers arrived in San Francisco in the mid-1800s, they definitely brought their appetite for oysters with them. But the ’49ers, while guilty of many things, may not have actually plundered and then destroyed the bay’s native oyster beds. Andrew Cohen, director of the Center for Research on Aquatic Bioinvasions, who has been investigating the story intermittently for more than a decade, thinks that the bay’s wild-oyster population could be about the same as or even greater than it was back in the day. “There’s no evidence to support the idea that native oysters were more abundant in the bay when the Europeans first showed up and were wiped out during the gold rush,” he says. “People who are trying to restore them are laboring under a misconception.”

Restoration-minded scientists in California agree that the historical record is spotty, but the overarching reasons to support native oysters are sound. “Oysters have always been present in the bay, and we know that they have benefits. I’m not sure it’s important whether they were enormously abundant 50 years ago, 500 years ago, or 5,000 years ago,” says Ted Grosholz, a professor of ecology at UC Davis. “Oyster restoration moves the needle for biodiversity, water quality, and other positive impacts.”

This article appears in the Winter 2022 issue of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

With the world’s biodiversity under serious threat—native species have decreased by 20 percent since around 1900—oysters and other foundation species, such as eelgrass, are becoming the latest poster children for conservation. While scientists can debate whether restoration is really the right term for what they’re doing, there is a sea change in how we are thinking about the environment at the water’s edge. Once sneered upon for being small and inconsequential, the West Coast’s Olympia—or Oly—is pointing the way to a more delicious, ecologically rich future.

A FISH STORY

In San Francisco Bay’s recent history, the modest mollusk casts a shadowy figure, but this was not always the case. Thanks to its sturdy calcium carbonate shells, it’s evident that Ostrea lurida was once an important food source. In a few of the 400-plus shell mounds created by Indigenous people around the bay, it shows up in huge numbers in layers that date back 2,000 years.

But for whatever reason, it appears that wild oysters were already elusive by the time hungry prospectors came to town in 1848. If their scarcity is to be blamed on the gold rush, then, as National Park Service historian Timothy Babalis writes in a 2011 article about the history of oystering on Point Reyes, “[the] hypothetical exhaustion of local oyster sources would have had to occur within the space of only three years.” A highly unlikely scenario.

“We like to tell stories which solve problems, and the notion of a bad colonial settler with the capacity to destroy nature is very tempting. It’s also an easy go-to because there are so many examples that are true,” says environmental historian Matthew Booker, the author of Down by the Bay: San Francisco’s History Between the Tides. “But it’s much more difficult to recognize complexity, and that is where environmental historians who study fisheries are going.”

Future oyster magnate John Stillwell Morgan unsuccessfully searched for oysters in the waters around San Francisco after he arrived in California in 1849, as detailed in the book The Oyster War: The True Story of a Small Farm, Big Politics, and the Future of Wilderness in America, by Summer Brennan. Newspaper accounts from that time also bemoan their absence. In the September 22, 1851, issue of the Daily Alta California, a City Intelligence columnist wrote: “Who will discover a bed of these luscious bivalves somewhere in the vicinity of San Francisco? What a luxury it would be to take a dozen natives, raw, out of the shell. It makes one’s mouth water to think of it, and an agreeable sensation steals through the inner man at the bare idea. Why cannot oysters be introduced from the coast of Mexico and planted and cultivated here?” (The columnist was likely writing an advertorial, since attempts to import oysters from Mexico were underway.)

Instead, by the early 1850s, enterprising merchants had discovered that there were large quantities of Olympia oysters in Washington. Demand was sufficient to keep several ships busy making the six-day voyage to Willapa Bay, just north of the Oregon border. Upon their arrival in San Francisco Bay, baskets of mature Olympias were laid in “oyster corrals” with underwater fences to prevent stingrays from eating them, keeping them fresh until they were brought to market.

But the small Oly was considerably less desirable than the larger Atlantic oyster (Crassostrea virginica). After the transcontinental railroad opened in 1869, oyster sellers switched to importing Atlantic oysters; Morgan was the first to bring in oyster “seed” in bulk and raise the baby oysters to maturity in the bay. In the 1890s, when Jack London was a young oyster pirate, sneaking around the bay on the Razzle-Dazzle under the cover of darkness, he was almost certainly poaching Atlantic oysters. Commercial oyster farming in the bay peaked in 1899 and went south quickly in the following years; the oysters stopped growing well around 1905, and increased awareness of water pollution likely reduced demand.

During the rise and fall of commercial oyster farming in the bay, the hometown Olympia kept chugging along, despite—or perhaps because of—the complete lack of interest in it. In his 1893 survey of the West Coast oyster industry for the U.S. Fish Commission, the earliest detailed record of oysters in the bay, Charles Townsend wrote that “this small [native] oyster abounds in San Francisco Bay, where it is utterly worthless as compared with the oyster from Washington,” and that it was “remarkably fertile.” As is true with native species in general, the Olympia is adapted to its specific environment; other oyster species have flourished but have difficulty reproducing in the bay’s chilly waters.

And the Bay Area Olympia is also distinct from its Washington cousin. As a PhD candidate at Oregon State University, David Stick performed a genetic analysis of Olympias on the West Coast and found five populations, including one specific to Northern California, which implies that there have been enough of them to hold their own over the years. “The genetic differentiation is consistent with, although not proof of, the presence of a large population of Olympia oysters native to San Francisco Bay,” says Grosholz, adding that it should be possible to extrapolate how large the population would have had to be in order to maintain its genetic identity.

THE CULTIVATED PALATE

Tastes—and values—have changed since the gold rush days. Along with many other native oysters, the Olympia is in Slow Food USA’s Ark of Taste, a “catalog of delicious and distinctive foods” threatened by extinction. “There’s always been a market for [the Olympia], and people enjoy celebrating its renaissance,” says Margaret Pilaro, executive director of the Pacific Coast Shellfish Growers Association.

Oyster lovers like to talk about how “merroir” (a riff on terroir), the waters that oysters live in, affects their taste. But according to Betsy Peabody, the founder and executive director of the Puget Sound Restoration Fund, the Olympia’s flavor is surprisingly consistent no matter where it’s grown: “What is really interesting about the Olympia is that it seems to hold to its taste—it has a distinct character that is not overtaken or swamped by the growing conditions. And that’s just a beautiful thing.”

In late September, I conducted my own taste test at Swan Oyster Depot, underneath a large black-and-white photograph of patriarch Sal Sancimino, Steve’s dad. The Atlantic oyster from Massachusetts tasted like salt water, and the Miyagi from Washington had a mysterious vegetal flavor. The Olympia I tried didn’t have a coppery taste. Instead, it had a rich brothy flavor. It was the most familiar, something that my taste buds could identify as food.

But it is easy to understand why the most widely cultivated oyster in the world is the Miyagi, also known as the Pacific oyster. Crassostrea gigas (meaning “giant thick oyster”) is the Red Delicious of oysters: it gets big quickly and adapts to a wide range of growing conditions. The Pacific oyster takes one year, compared with three years for an Olympia, to reach maturity, at which point it is three to four times the size of an Olympia. While its name suggests that it is native to the West Coast, the Pacific oyster was rebranded after World War II. It is from Japan, and it was originally called the Miyagi, for Japan’s Miyagi Prefecture. Both the Pacific and the Olympia oysters got their names from Earl Newell Steele, a local politician and oyster grower in Olympia, who was obviously an early brand-identity expert, according to historian Booker.

Sal Sancimino, who purchased Swan Oyster Depot with his cousins in 1946, had served in the military during the war and refused to put Japanese oysters on the menu. His son Steve, who is 70, grew up eating Olympias imported from Puget Sound. After Steve and his brothers took over the business in the 1970s, they got rid of the ban; today, most of the oysters they serve are Pacific oysters.

Washington’s huge oyster industry got its start by exporting Olympias to San Francisco and continues to supply a niche market for them. Taylor Shellfish Farms, one of the largest oyster growers in the United States, began in the 1890s by farming Olympias in south Puget Sound’s Totten Inlet. Out of the approximately 50 million oysters a year it sells today, a tiny percentage are Olympias. “They are a more delicate oyster to raise,” says Bill Dewey, director of public affairs for the company. Olympias are highly sensitive to sediment, extreme temperatures, and salinity. In the Bay Area, recent oyster die-offs have coincided with seasonal flooding.

Meanwhile, there are two companies in California, Bodega Bay Oyster Company and Hog Island Oyster Co., that cultivate a limited number of Olys in Tomales Bay, a 15-mile-long inlet north of San Francisco. “I think people want to feel more connected to the longer arc of their food systems—people really are interested in eating more local native stuff,” says Gary Fleener, science, sustainability, and education specialist at Hog Island. “One of the coolest things about oysters and mussels is, even though we say we farm them, 100 percent of what they’re eating is wild. They’re just out there filtering plankton,” he adds. “We’re just keeping them in little cages so we can pull them out of the water more easily.”

Fleener and others cite the popularity of the Kumamoto, another small, slow-growing oyster, as a reason to be optimistic about Olympias. “Some people prefer a cocktail-size oyster so they can participate in the cult of oyster eating without having to wrestle down these big ol’ oysters,” says Fleener. “Olys can definitely play in that space.” He says they could sell quite a few more Olympias than the 50,000 a year they produce now, but the profit margin on them is substantially lower despite their premium pricing.

WHAT LIES BENEATH

Besides their new status in the locavore movement, native oysters have a role as nature’s architects, doing their part to fight climate change. Building upon the layers of oysters that came before them, Atlantic and Pacific oysters form reefs, which protect shorelines from erosion by slowing down incoming waves—what scientists call wave attenuation. As the world grapples with storm surges and rising sea levels caused by global warming, policy makers are considering “green infrastructure,” including wetlands and artificial reefs, in lieu of or in addition to traditional “hard” infrastructure such as seawalls or riprap.

In 2009, Kate Orff, the first landscape architect to win a MacArthur grant (in 2017), designed a conceptual project called Oyster-tecture, a human-made reef populated by oysters, mussels, and eelgrass to help buffer New York City from rising sea levels. Last summer, construction started on a $107 million Living Breakwaters project off the coast of Staten Island, designed by Orff’s firm, Scape. Where there once were naturally occurring oyster reefs, 2,400 linear feet of breakwaters are now surrounded by underwater concrete structures, encouraging oysters and other marine life to take up residence. The breakwaters, which are made of piles of rocks, are doing the heavy lifting. But the hope is that the oysters will embellish the reef-like structures with a living veneer, creating more aquatic habitat and augmenting the wave-slowing effect of the breakwaters. Oysters are ecosystem engineers, creating a habitat that provides hidey-holes for other invertebrates, nurturing sources of food for fish, birds, and crabs. “The way we talk about global warming is usually dark and pessimistic,” Orff said in a past interview. “It can be stifling. Part of my job is showing people new ways to see things, to offer a vision of places we can live in, responsibly, and also enjoy.” Scape also designed China Basin Park in San Francisco, which will have a shoreline of “tidal shelves,” a constructed environment for native species like oysters, instead of the riprap that is there now.

There is currently a lot of hype about oysters’ filter-feeding systems and their ability to clean our waterways. And biologists are understandably wary of overpromising and underdelivering. While one Olympia can process 8 to 12 gallons of water a day, the turbidity of the water in San Francisco Bay is mainly due to inorganic silt, not the microscopic algae that oysters eat. “Even in the long term, oyster restoration is unlikely to mitigate in any substantial way the increasing effects of human inputs of nitrogen and other nutrients into Puget Sound,” states the 2012 update to Washington’s oyster restoration plan.

Because they don’t form reefs, Olympias aren’t the infrastructure builders that Pacifics and their East Coast counterparts are. But their shallow beds still provide an underwater habitat, and they are also being used to zhuzh up “living shorelines.” In San Francisco Bay, which has lost an estimated 90 percent of its original wetlands, the focus had previously been limited to wetland restoration. But in the past decade, ecologists have made the most of limited budgets by combining restoration with shoreline protection, turning their attention to habitats below the water’s surface as well as farther upland in order to counteract rising sea levels.

The most recent living shoreline project in the bay is at the Giant Marsh, located in the sleepy outskirts of Richmond in the East Bay. The first phase of the $3 million project, which encompasses 2 acres of aquatic habitat but is projected to benefit some 200 acres, was installed in 2019. If you time your visit to low tide, you might see the closest of three oyster “reefs,” made from concrete blocks and “reef balls,” hollow spheres with many holes on their surface, which were craned into place. Early studies show that the reefs help with wave attenuation, and in the past two years, they’ve been colonized by free-floating Olympia oyster larvae from parents somewhere in the bay. Also offshore are new beds of native eelgrass, which help to further stabilize the shoreline and provide shelter for fish. Heading toward shore, there’s native cordgrass at the water’s edge and plantings of locally extinct sea blite, a salt-tolerant native shrub. Because it’s supposed to mimic the native habitat, a layperson will have a tough time distinguishing the project area from the rest of the marsh, which is not particularly giant—it’s named after the historical town of Giant, California, not for its size. In fact, the most visible things offshore are the old pilings of a wooden railroad trestle. It was built to transport dynamite from local explosives plants, which operated until 1960. “The bay is a very different place than it was even 100 years ago,” says Grosholz.

BUILD BACK BETTER

Aquatic Bioinvasions’ Cohen contends that Olympias may not need saving in California. The oyster myth buster reached this conclusion after searching for turn-of-the-19th-century records of harvestable beds of wild Olympias anywhere south of Yaquina Bay, 200 miles north of the California border, and finding none.

Perhaps he is right and Olympias were never plentiful to begin with. But now their populations appear to be declining. In the mid-2000s, researchers conducted the first wide-scale survey of Olympias on the West Coast, which have been found between Alaska and Baja California, and discovered them at 19 out of 24 historical locations (but not at the two extremes). “It’s a glimmer of hope for restoring them,” says Danielle Zacherl, a professor of biology at Cal State Fullerton, who was a coauthor of the resulting 2009 paper. “Finding them in all these locations was one thing, but there was no place where they were living in anything close to a habitat-forming situation—definitely not forming oyster beds anymore. It was sort of like they were eking out an existence as remnant populations.” Another paper, which was just submitted for publication, compared quantitative records of Olympia populations pre- and post-2000 and found that they have declined both in numbers and in their distribution. It also found that Pacific oysters (likely escapees from hatcheries and boats) have started to colonize the coast, while the native Olympia oysters have lost ground to the point where the two can be found in about equal numbers.

In Elkhorn Slough, located between Santa Cruz and Monterey, researchers are running a life-support system for Olys, which appear to be on the verge of going locally extinct. They are breeding oysters in a lab to increase their numbers, an experiment in conservation aquaculture. But the natural condition has been significantly altered: surrounded by commercial agriculture, the meandering waterway is polluted with fertilizer runoff and constrained by dikes that limit the tides. “The fundamental plumbing of the slough was drastically rearranged,” says Kerstin Wasson, research coordinator at the Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve and a cofounder of the Native Olympia Oyster Collaborative, a network of research institutes, government agencies, and nonprofits. According to Wasson, about 50 percent of the estuary that would have been good oyster habitat no longer exists. “Thriving oysters, along with pickleweed in the salt marsh and eelgrass—the three foundation species in California estuaries—would be an indication that Elkhorn Slough is returning to a more natural, healthy state.”

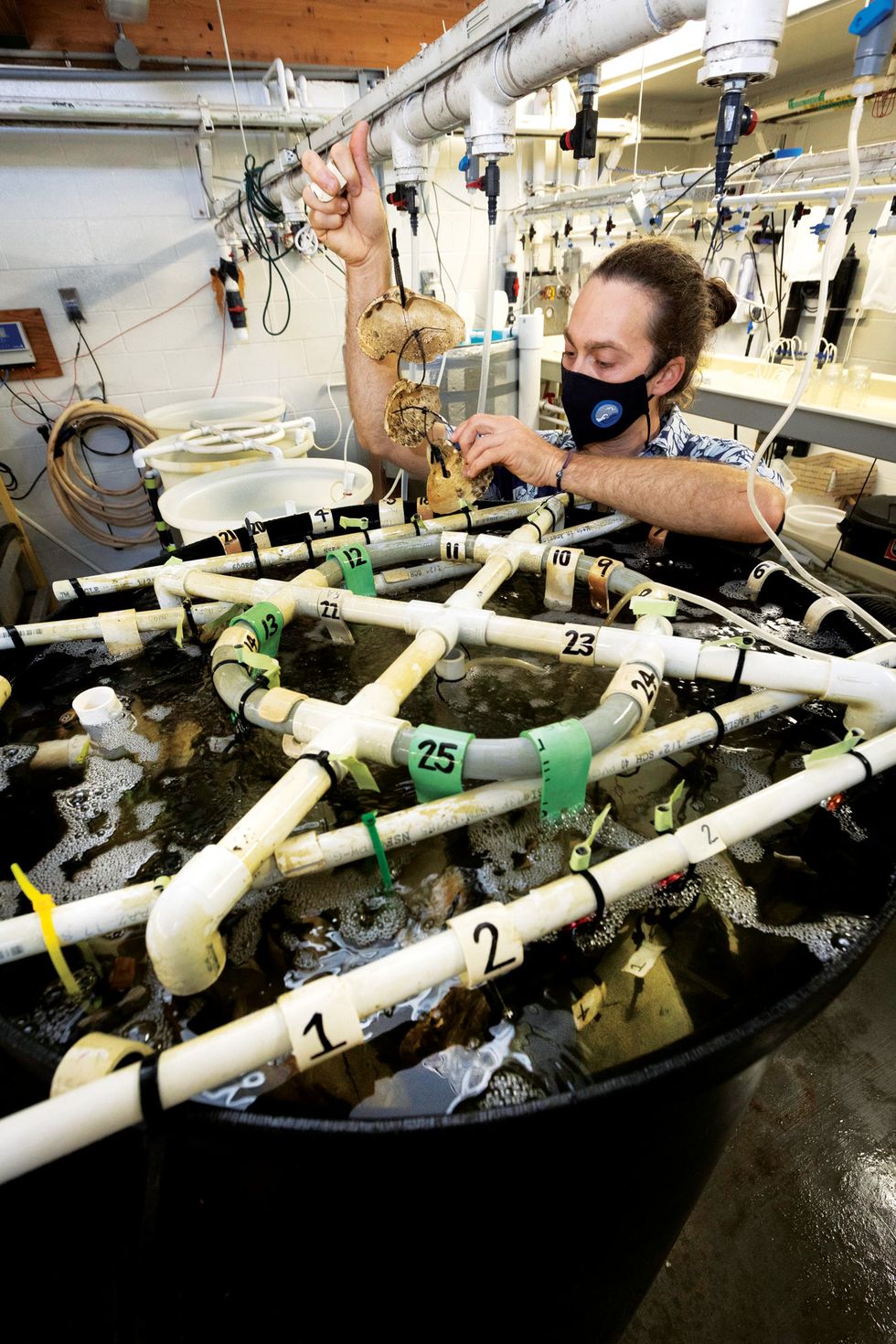

After observing the tiny wild-oyster population of about 5,000 decline steadily over a decade, Wasson and scientists at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories started a small-scale oyster hatchery in 2018. A brightly lit room is devoted to making baby-oyster food; 50-gallon fiberglass tanks are filled with vibrant yellow and green liquids containing cultured microalgae. In June, the team brought back approximately 500 oysters that were hatched in the lab in 2018 and grew into adults in the slough. Once in the lab, they were prompted to spawn by raising the water temperature in their tanks. The resulting oyster larvae settled onto tiles, oyster shells, and abalone shells in another set of tanks and have grown into tiny oysters. In the fall, they will be transported into the slough, anchored to sticks with zip ties.

It’s unclear why the remaining wild oysters, which have dwindled to about 500 today, have been unable to add new members to their population. Among Wasson’s theories is that there are simply not enough oysters to be self-sustaining, and any baby oysters that show up were larvae that rode the currents all the way from San Francisco Bay. (In Stick’s Oregon State University dissertation, San Francisco Bay Olympias have genetic overlap with those in Drakes Bay, Elkhorn Slough, and Humboldt Bay.) She’s also optimistic that since the adults seem to be thriving, there may be some locations in the estuary where the conditions are just right for population growth. In a couple of other places that were down to their last remaining wild oysters, restoration efforts have made a difference. After getting an infusion of more than a million baby oysters each, Fidalgo Bay in Washington and Netarts Bay in Oregon, which had just a few oysters in the early 2000s, now have self-sustaining populations of Olympias.

Wasson has secured a grant to hire members of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band to work on oyster restoration at Elkhorn Slough. “They’re interested in regaining a connection to oysters and relearning marine stewardship techniques from us, while we learn perspectives on marine resources from them,” says Wasson.

In Washington, oyster restoration is important to tribes that once organized their settlements around oyster harvests and went to court to retain their rights to harvest shellfish. There are places like Patos Island, whose Samish name is Tl’xwóyten, or “place where you get oysters.” The Squaxin Island Tribe, which has direct governance over 500 acres of tidelands in south Puget Sound, is one of several tribes actively involved in restoration.

“It’s cultural tradition and was part of their food supply for many millennia. The idea would be to be able to use [Olympias] for various celebrations and funerals and so forth, where shellfish is a common part of the menu,” says Jeff Dickison, the assistant director for natural resources for the Squaxin Island Tribe.

The tribe has provided locations for oyster beds, along with staff time and other resources, to the restoration. Some of its members harvest wild oysters along with other shellfish species for ceremonial and subsistence purposes, and the tribe owns a commercial fishery that grows Olympias as well as Pacific oysters and Manila clams.

One hundred and thirty years after Townsend did his survey, there is no good current estimate of the Olympia population in San Francisco Bay. But the bivalves are definitely out there. “We did estimate three to four million just at one location, so it’s not unrealistic that you could get to billions [of adult Olympias] around the bay,” says Chela Zabin, a biologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center who works on Olympia restoration. “It is easy to find them if you know what you are looking for and go to certain sites at low tide.”

One morning this past September, I went to the Marine Science Institute in Redwood City, which has been educating schoolchildren about bay ecology since 1970 and where I’d heard it might be possible to find Olympias. Jesús Jimenez, MSI’s aquarist and facilities engineer, met me in the gravel parking lot. He led me to a blue plastic dock near where Redwood Creek empties into the bay and showed me how to do “belly bio,” one of the educational activities for kids. I lay on my stomach and put my arm into the green water. The underside of the floating dock was completely encrusted with sea life, also known as “marine fouling”—bad for boats, great for belly bio. I felt the smooth convex shells of mussels, the squishy stems of sea vases, and the rough concave shells of oysters, all jam-packed together. With care, I detached about a dozen Olys, the largest of which was about two inches long, and placed them in a clear plastic tub, destined for the MSI aquarium. “There’s a lot of non-native species in the bay, so it’s fun and a good opportunity to teach when you find something that is native,” said Jimenez.

During the gold rush, loggers in the mountains had used this creek as a conduit for felled redwoods, which were loaded onto rafts and sent up the bay to help build San Francisco. As I spoke with Jimenez, members of a local rowing club sculled by. Behind us, cars whizzed back and forth along Highway 101. The glassy office towers in Redwood Shores, a suburb created by filling in the bay, were visible to the north. In the water in front of me, Olys were making the most of their limited real estate. Seeing the world under the dock, I felt greedy. I wanted to have more of everything—oysters, mussels, fish, birds, seals—around us.•

Lydia Lee writes frequently about design and architecture in the San Francisco Bay Area and is a local bicycle advocate.