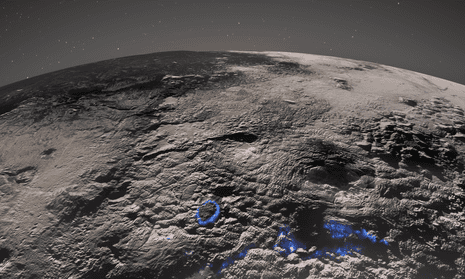

Strung out in the icy reaches of our solar system, two peaks that tower over the surface of the dwarf planet Pluto have perplexed planetary scientists for years. Some speculated it could be an ice volcano, spewing out not lava but vast quantities of icy slush – yet no cauldron-like caldera could be seen.

Now a full analysis of images and topographical data suggests it is not one ice volcano but a merger of many – some up to 7,000 metres tall and about 10-150km across. Their discovery has reignited another debate: what could be keeping Pluto warm enough to support volcanic activity?

Sitting at the southern edge of a vast heart-shaped ice sheet, these unusual surface features were initially spotted when Nasa’s New Horizons spacecraft flew past in July 2015, providing the first close-up images of the icy former planet and its moons.

“We were instantly intrigued by this area because it was so different and striking-looking,” said Dr Kelsi Singer, a New Horizons co-investigator and deputy project scientist at Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

“There are these giant broad mounds, and then this hummocky-like, undulating texture superimposed on top; and even on top of that there’s a smaller bouldery kind of texture.”

At the time, an ice volcano seemed like the least-weird explanation for these features – there were no impact craters from asteroids or meteors nearby, suggesting these features had been erased by relatively recent geological events; and no evidence of plate tectonics – a key contributor to mountain formation on Earth.

Yet, Singer and her colleagues were cautious about calling them volcanoes: “It’s considered kind of a big claim to have icy volcanism,” she said. “It’s theoretically possible, but there aren’t a tonne of other examples in the solar system, and they are all really different looking, and do not look like the features on Pluto.”

Since those first images were beamed back in 2015, many more have arrived, along with compositional and topographical data. Taking all of this together, the team has concluded that these unusual features really are volcanoes – although their appearance and behaviour is very different to those found on Earth.

“If you look at Mount Fuji from a distance or one of the Hawaiian volcanoes, they look like these big, broad, smooth features, which is just not what we see there,” said Singer, whose findings are published in Nature Communications. “So, we think, probably the material is extruded from below, and the dome grows on top.”

As for the nature of this material, the compositional data suggests it is mainly water ice, but with some additional “antifreeze” components mixed in, such as ammonia, or methanol. “It is still difficult to think that it would be liquid, because it’s just too cold – the average surface temperature on Pluto is about 40 Kelvin (-233 C),” said Singer. “So, it’s probably more, either slushy material, or it could even be mostly solid state – like a glacier is solid, but it can still flow.”

Even this is quite surprising, she added, because, given the extremely low temperature, this material shouldn’t be mobile at all. Possibly, it suggests Pluto’s rocky core is warmer than anticipated, and that heat energy released from the radioactive decay some of its elements is being somehow becoming trapped, for example by an insulating layer of material, and periodically released, triggering volcanic eruptions.

All of this is speculation. “I will freely admit we do not have a lot of information about what’s going on in the subsurface of Pluto,” said Singer. “But this is forcing people to come up with some creative ideas for how [ice volcanism] could happen.”

Whatever the explanation, the old idea of Pluto as just an inert ball of ice is looking increasingly improbable.