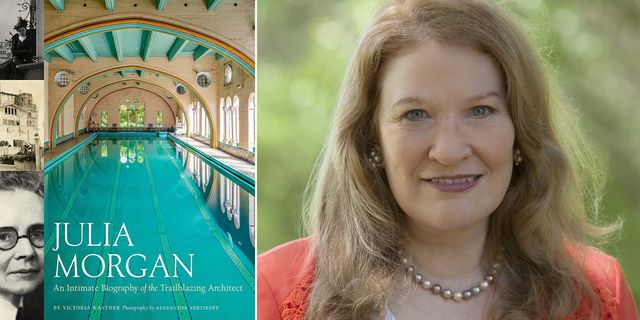

In her introduction to Julia Morgan: An Intimate Biography of the Trailblazing Architect, Victoria Kastner summarizes her subject with a single word: “strength.” Indeed, the California-born Morgan was not only tough but also resilient; in the face of the many formidable glass ceilings she encountered, she had to be.

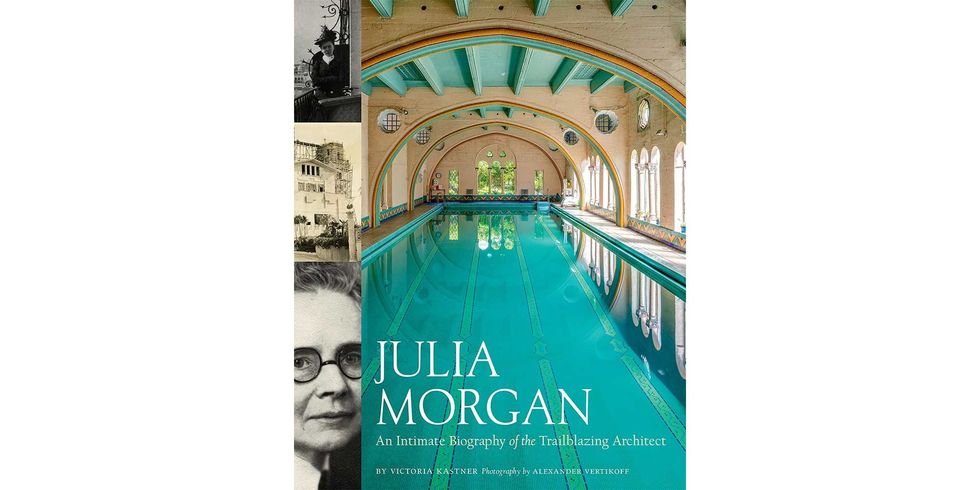

In 1894, she became one of the first women to graduate from UC Berkeley with a civil engineering degree. Four years later, she was the first woman to attend the École des Beaux-Arts architecture program in Paris. In 1904, she became the first licensed female architect in California. Over the course of her career, Morgan would design more than 700 structures throughout the western United States—most famously, Hearst Castle in San Simeon. She remains among the most prolific female architects in history.

For Morgan, however, strength was more than an asset—it was a lifelong obsession. Her prodigious output and accomplishments can be chalked up, in part, to what Kastner calls her “exceptional reserves of stamina and energy.” At the same time, she pushed herself to troubling extremes in the pursuit of productivity. She came of age during the Second Industrial Revolution, that advent of mechanization and mass production, so it is perhaps unsurprising that Morgan would model herself after a machine.

“You wouldn’t treat an engine the way you treat yourself,” Morgan’s patron William Randolph Hearst wrote to her in 1928. She had just suffered heatstroke at the site of Hearst Castle, the estate on which the two would collaborate for nearly three decades. He implored her to “stop working so hard. All your friends will be really angry with you if you don’t.” The two shared an intimate working relationship as well as a close friendship, but, as Kastner emphasizes, things never turned romantic. In fact, there is no evidence that Morgan ever had romantic involvements of any kind, which makes for a sadly chaste biography.

Architecture, Kastner writes, was Morgan’s “lifelong love affair.”

Morgan’s need to work outweighed other necessities, including food and sleep. Her draftsman Bjarne Dahl “often wondered why she didn’t eat more.” In the course of her work on Hearst Castle, she took 568 trips to San Simeon—a 10-hour journey, one-way, from her office in San Francisco. She would head south on Saturday night, arriving in the early hours of Sunday morning, then spend the day scaling scaffolding and liaising with contractors before returning to the Bay Area in the evening. She never stayed overnight.

Come Monday morning, Dahl recalled, “she’d go right to the [office] door and go to work…. She was never tired.” Moreover, Morgan seemed to derive pleasure from her grueling schedule: “One generally is happy, if busy,” she once wrote to the son of friends.

Her dedication had physical consequences. Morgan had to take the École des Beaux-Arts’ infamously grueling entrance exams three times before she was admitted, and she fell seriously ill from the intense preparation required. (She dismissed her medically mandated rest as “so wasteful of time.”) Such grit may have seemed to her a necessity—the only feasible response to the pressures that came from feeling, as Morgan must have, like a representative for all working women.

Certainly, Morgan had a lot to prove. When she took the École des Beaux-Arts exams for the second time, the admissions committee declared that it would not want to encourage young girls—ne voudraient pas encouragé les jeunes filles. “I’ll try again next time anyway even without any expectations,” she wrote to friends, “just to show [them] ‘les jeunes filles’ are not discouraged.” After her acceptance, she was written up in the local paper, the Oakland Tribune, which made a point of praising her for being “as pretty as she is bright” and “decidedly effeminate.”

Kastner concedes that Morgan “often failed to take proper care of herself” but is more interested in her “inspiring” life. Having spent nearly four decades as Hearst Castle’s official historian, the author has done her research and relays it with fastidious care. The biography sometimes veers into hagiography as Kastner zeroes in on Morgan’s good deeds and virtues (her pro bono work, her advocacy for women’s suffrage, her generosity toward employees) while overlooking her flaws, weaknesses, or fears—that is, what made her a human rather than a saint.

Perhaps this is why, despite its many insights, Julia Morgan never quite lives up to the subtitle’s promise: “An Intimate Biography.” Even in her diaries and correspondence, Morgan was fairly guarded, bordering on inscrutable. It’s disappointing but not a deal breaker, for the biography does succeed in capturing Morgan’s far-reaching legacy, exploring the histories of California and 20th-century architecture in the process. Although Morgan the woman remains somewhat elusive, Kastner makes an unassailable case for her as the patron architect of California.•

Sophia Stewart is an editor and writer from Los Angeles. She is the recipient of a 2021–22 National Book Critics Circle Emerging Critics Fellowship.