Since my aunt, Joan Didion, passed on December 23 of last year, not a day goes by when I don’t think to myself, Thank God I made that doc. Viewership of Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold on Netflix has accomplished what I hoped: that her devoted readership would see her not as the queen of doom, as she was often described, but as the laughing, dry-humored woman I grew up with. I also hoped, even more, that a young audience would be drawn to her character and then read the books we covered in the film. Her sales have surged yet again, so mission accomplished.

Our collaboration on the documentary began with another project; in 2011, Joan suggested to her publisher that I make the promotional video to accompany the release of Blue Nights, her book about the death of her daughter, Quintana. I had directed several feature films but had never taken on a documentary. Both Joan and her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, had always given notes on rough cuts I’d directed and read early drafts of screenplays I’d produced. We’d also worked together when my partner Amy Robinson and I developed John’s book Vegas: A Memoir of a Dark Season for 20th Century Fox, with him and Joan writing the screenplay. So, Joan must have assumed my filmmaking experience made me up to the task. In typical Joan fashion, she didn’t ask me directly but had someone from Knopf make the call.

As sorrowful as the book Blue Nights was, shooting the promo was a delight. Joan once entertained a childhood dream of being an actor, and she had a ball piling into the van with our crew, rushing from location to location. The crew, in turn, were spellbound to be in her company and, during our lunch breaks, peppered her with questions she seemed happy to answer. David Hare, the director of the Broadway production of her play The Year of Magical Thinking (adapted from her memoir), said in my documentary that she seemed to come alive during his rehearsals, joyous to be part of a company sharing the same vision. That could describe my experience as well.

After the Blue Nights video was well received by Knopf editor in chief Sonny Mehta and his marketing department, I got up the nerve to ask my aunt something that had been on my mind for weeks.

“Joan, how would you feel if we took this project one step further and made a full-length documentary?”

She looked at me with an unreadable expression. Had I pushed my luck? Had I crossed the line?

“Ummm,” she began. OK, never mind, I was about to interject.

“Well…,” she continued, still looking at me. Right, bad idea, I get it.

“Sure. Fine.” That was all I got.

“Fine, yes?” I asked.

“Yes, fine, I said yes,” and that was the end of that subject.

My elation was soon tempered by the burden I’d volunteered for. I realized it was now my job to tell the life story of a woman whose devoted (and sometimes rabid) following felt personal ownership because of the effect her work had on their lives. In countless interviews, people testified that they had become writers because of her, that they read “On Self-Respect” every year to realign their morality, or that they were Maria from Play It As It Lays. (A disturbing admission.) I hadn’t shot a foot of film and already I was bracing for a tough audience.

This article appears in the Spring 2022 issue of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

I flashed back to my teenage self who once asked her, “Hey, Joan, what are you writing now?”

My uncle John, overhearing, boomed, “You never ask a writer what they are writing while they are writing!”—which curled me inward with embarrassment. If I couldn’t even get that answer, I now worried, how was I going to get her to talk about a heady piece like “Sentimental Journeys” or “Cheney: The Fatal Touch”?

Calming myself, I thought about why Joan must have agreed to let me tell her story. She’d been approached many times by other filmmakers, whose requests, I imagined, had been delivered in the kind of overly fawning fashion that she never responded to. Or with a dry, academic, and forensic approach to her work that would have bored her silly. I realized that she was trusting me with this project because I had actually known her almost all my life.

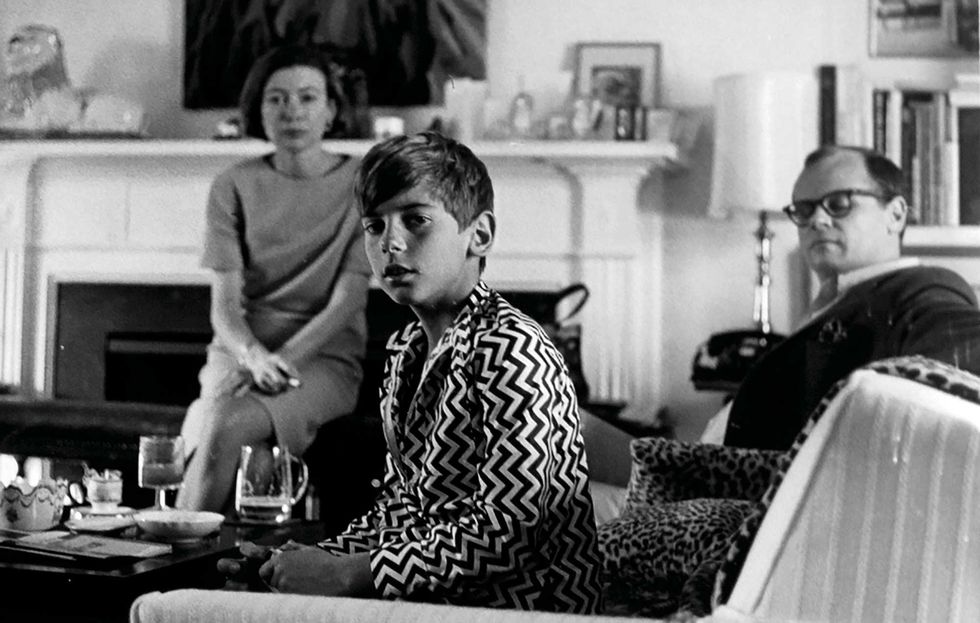

From my earliest teens, she and John had included me at their dinners in Malibu, seating me beside a homicide detective or a movie star. When I was 11 years old, she called my mother to invite her to a party they were giving for Tom Wolfe to celebrate the release of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. “Bring Griffin,” she said. “Janis Joplin is coming, and I know he loves her.” When the first film I directed, about that very party, was nominated for an Academy Award in the shorts category, Joan and John sent me champagne and caviar from Petrossian.

Not long after she gave me the go-ahead for the doc, Joan was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. It came as no surprise to those of us in her tight-knit circle, because her health had begun to decline, and we knew to keep this news secret. I’d yet to get financing but had recently been paid for an acting gig, so I immediately hired a crew to shoot her interviews at various locations in New York. During our filming, the fun Joan and I had had the first time around came roaring back, except for the day we found out her great friend Nora Ephron had died. Joan was devastated, and we quickly wrapped and sent her home. Another time, I felt disadvantaged to be her nephew while asking her to relive the moments of John’s and Quintana’s deaths, something an objective documentarian would have no qualms about doing, but Joan was a journalist and would not have respected me if I hadn’t.

Once my shooting with her was complete, my editor, Ann Collins, and producers Mary Recine and Annabelle Dunne (my cousin) set up our interviews with Hare, writer Hilton Als, and many others while mining every piece of Didion archival footage we could get our hands on.

My first cut ran over three hours. I would never have shown a film that long to Netflix, but Joan was another matter. I was far enough along for her to tell me if she hated it and thought I had botched her life story, but not so far in that I couldn’t give Netflix its money back if it turned out I was in over my head.

In her apartment, I set up a laptop with two speakers on a dining room table that had made its way from Los Angeles to the Upper East Side and where I’d spent decades of Easters and Thanksgivings wolfing down ham and tamales. Joan placed herself in front of the screen, and her dog, Ellie, made herself comfortable at the foot of her wheelchair. I explained that the movie had a time code, so if at any point she had a question or concern, I would mark the place so we could discuss it when we reached the end. At the halfway point, I said, we’d stop to take a bathroom break. She looked like she wasn’t listening, but I could tell she was nervous. Nowhere near as nervous as me but nervous nonetheless.

“OK,” she said, meaning Stop talking and start the thing already.

A few minutes into watching, her eyes teared up when she saw the Big 5 notebook she’d written in as a child, then again during the account of her early years in New York writing for Vogue, where she learned to stick to “action verbs, action verbs” from her editor Allene Talmey, and then when she heard herself reading her description of her father, who suffered from depression.

Emotions got the best of her once more when we got to the part about John dying. When the time code read 1 hour and 30 minutes, I stopped the film as I’d said I would. Joan whipped her head to me with a look as if I’d just kicked her dog.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“Remember I said that we could take a bathroom—”

“Keep going!” she demanded. “Keep going!”

I tried to imagine what this viewing experience must be like for her, or what it would be like for anyone in their 80s to see their entire life unfold before them. What must it be like to see friends and colleagues talk about your life’s work and family so knowingly? To hear your few surviving friends (because she’d outlived so many others) describe you at your highest and lowest moments? To realize how hard people have worked to find the perfect music and discover the most forgotten archival photos that make up the sum of an extraordinary life?

When it was over, we sat motionless for what seemed an eternity, her eyes still fixed on the laptop’s now-blank screen.

After composing herself, she finally looked at me and took my hand. “Thank you,” she said. That was all I needed to hear. Never have two words meant more to me in all my life. Then I began to tear up, and she squeezed my hand a little tighter.

We debuted The Center Will Not Hold at the New York Film Festival in 2017. It’s the custom of the organizers there to put the filmmaker and the cast, in this case Joan, in the balcony so that at the end of the movie a spotlight can find them and they can stand and wave to the crowd. I spent most of the screening fretting about that moment because I was having a nightmare vision that while I was helping Joan out of her wheelchair and to her feet, she would lose her balance and fall into the mezzanine. It was a ridiculous fear because my mother was handicapped and I’d brought her to a stand for most of her life, but that’s how my nerves played out to deflect the bigger worry of how the film would be received.

Any doubts I had about the audience’s reaction were put to rest when we got a seven-minute standing ovation. (The longest in the event’s history, the festival’s director told me that night.) The ovation was really for Joan, for her years of brilliant writing, for surviving unbearable heartbreak, and for how she kept moving on like her ancestors who crossed the plains to settle in the Sacramento Valley.

I rose and gazed down at her during the thunderous applause with a Do you believe this? expression.

She looked back at me and said through gritted teeth, “Get me up!”

She hardly needed my help, and we stood looking at the faces below, many people in tears, all clapping upward, sending warm currents of love in her direction.

I’m proud of the film, but I’m most proud that I was able to give her those seven minutes. Reading a book is a solitary experience, and writing one more so, and few authors get to see what their life and their words have meant to people as she did that night. I made that possible for Joan, and she made it possible for me to leave something behind—about who she was and where she was from. •

Griffin Dunne lives in New York, where he works as an actor, writer, and director. He can currently be seen in the NBC series This Is Us.