Imagine the art you could buy with $40,000. A Picasso drawing. A Judy Chicago. An Ed Ruscha. Whatever it might be, a few pixelated animals on the internet probably don’t come to mind.

Fedya Chobanyan, however, claims that purchasing these digital works, called NFTs, would be the better choice. The 19-year-old is an amateur mixed martial arts fighter who trains in North Hollywood. Since he doesn’t yet earn income from his bouts, he’s quite proud of the collection of three items he’s already amassed. Not only does Chobanyan consider his NFTs to be works of art; he also believes they will one day help make him rich. He declines to say how much he paid for the NFTs, but the combined value of three similar items is currently hovering at around $40,000, or 12.86 in the cryptocurrency Ether. If Chobanyan were to offer up his NFTs today, he estimates, they would fetch 30 times what he originally paid.

Spending anything—let alone hundreds or thousands of dollars—on something that cannot be touched, tasted, or enjoyed in person might sound ludicrous, but Chobanyan is far from alone in this endeavor. Last year, NFT sales reached $25 billion. Their value was increasing so rapidly that many purchased them and flipped them days later for significant profits.

After acquiring his latest NFT, a 2-D shark, part of a series titled Marine Marauderz, Chobanyan tweeted, “Some guy just laughed at my profile pic! I’ll laugh when I make $$$$ out of @MarineMarauderz! Some people will laugh at you then ask you how you did it! Knowledge is everything! Some people don’t have any of it!”

A curious aspect of the NFT market is that not everyone who owns one is “in the know.” Unlike in the traditional art world, where would-be collectors without riches or a blue-blood pedigree are often looked down on, anyone can get in on NFTs. There are no black-turtlenecked gallerists staring you down for asking what the red dot next to a painting means or for wearing clothes that are not exactly haute couture. And enthusiasm is rewarded. The self-professed real students of this marketplace claim that buying the right NFT opens doors to various ecosystems of support, camaraderie, status, and business opportunities. While different groups rally around different NFTs of, say, drowsy apes, humanoid turtles, bears, or even punk rockers, there’s one thing they have in common. Their members believe that they are at the forefront of a revolution—built on cryptocurrency—that will disrupt the very ways society uses monetary systems, technology, and art.

This article appears in the Spring 2022 issue of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

But not everyone is a fan. This so-called revolution strikes at something many hold sacred: the relationship between artist and art, the meaning in an act of creation. What’s happening now is larger than the traditional tension between art and commerce, and it’s occurring at internet speed. As musician and record producer Brian Eno told the Crypto Syllabus, “NFTs seem to me just a way for artists to get a little piece of the action from global capitalism, our own cute little version of financialisation. How sweet—now artists can become little capitalist assholes as well.”

NFTs AT WORK

An NFT, or non-fungible token, uses blockchain technology—the same computationally exhaustive code that underpins cryptocurrency—to store information about a digital asset’s owner, transaction history, and other key details. Since the code for each asset is unique, the asset is considered non-fungible, meaning that it cannot be tinkered with. This quality is useful for proving ownership of everything from online art pieces to songs to virtual land.

In other words, an NFT is a digital certificate. What it really does, on a practical level, is generate buzz for an item’s exclusivity. For instance, if an artist were to design a set of digital coffee mugs, or use an algorithm to create thousands of varied mugs (as the most popular NFT series do), they would not have much value since anyone could copy and share them; there would be no way of proving which were the original mugs. But if that project were made into NFTs, or, more accurately, “minted” as such, each mug would be recorded on the blockchain and have a unique identifier. The image could still be copied, but the blockchain technology would indicate which item was authentic and be able to track it, potentially increasing the original set’s value through scarcity while allowing the creator to collect royalties each time an original mug was sold.

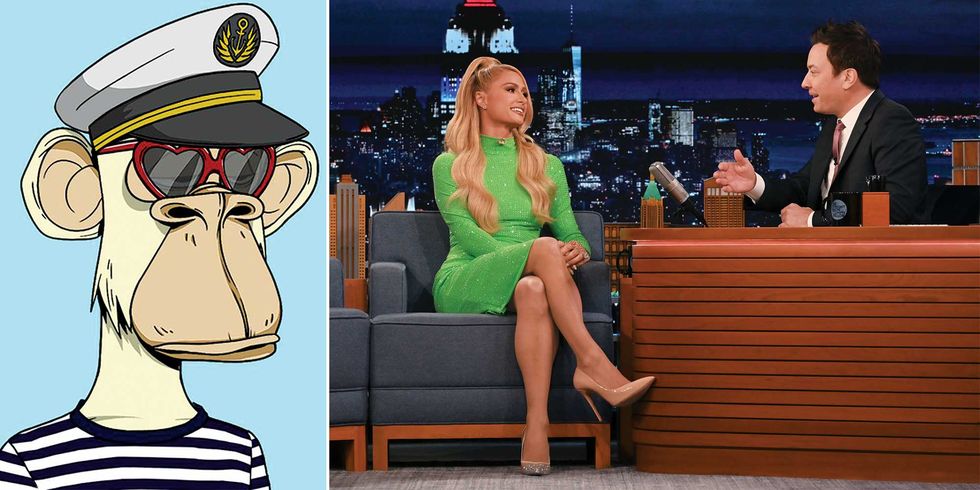

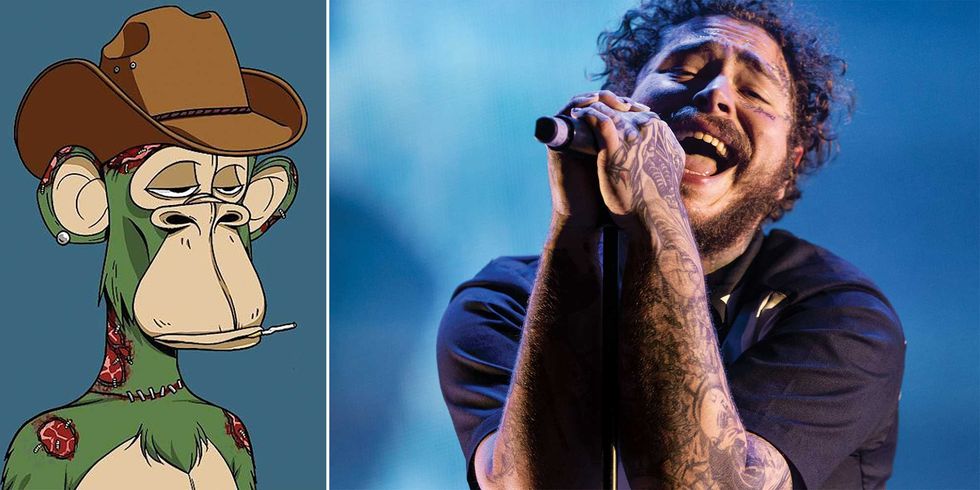

Jimmy Fallon, Martha Stewart, and Paris Hilton are some of the celebrities who’ve recently hopped on the non-fungible bandwagon. Some stars have even launched their own NFT projects to promote charities. Mostly, their enthusiasm for the tokens can be boiled down to an attempt to stay relevant or to flaunt their high-roller status, as in the music video for Post Malone and the Weeknd’s “One Right Now,” which shows Post Malone buying a Bored Ape—one of the most popular and expensive NFT projects—on the crypto marketplace MoonPay. He reportedly shelled out over $700,000 (160 Ether) for two of the apes.

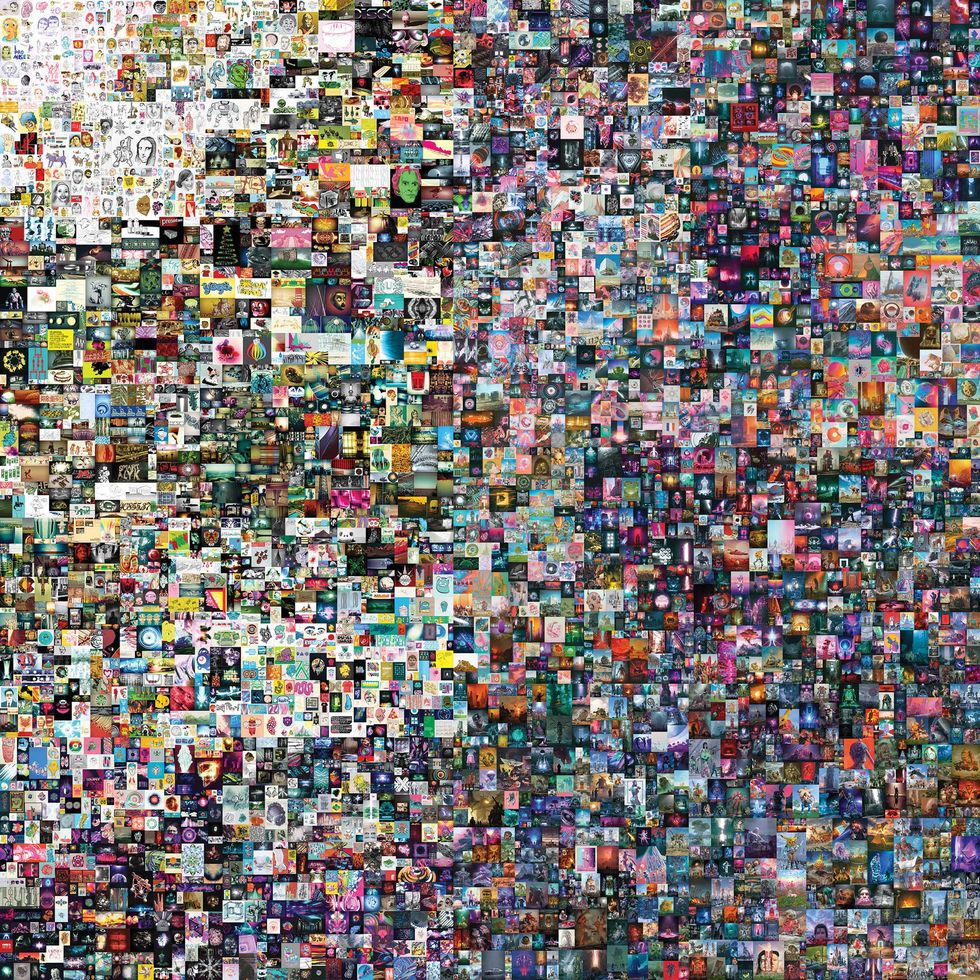

Making Post Malone’s $700,000 look like child’s play is the $69 million purchase of Everydays: The First 5,000 Days, an artwork by Michael Winkelmann, better known as Beeple. The sale, which was facilitated by auction house Christie’s, simultaneously made Beeple the third-richest artist alive and elevated NFTs to the hottest topic in the art world.

New Media Danger

When Steven Sacks founded Bitforms Gallery in 2001 in New York City, he knew that promoting art that used the latest forms of technology (what some call new media art) would be a challenge. Audiences were mostly unfamiliar with the concept, and very few collectors or museums were interested in doing shows. Today, Sacks is hailed as the “king of digital art,” and Bitforms Gallery also hosts shows in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and across the globe. While Sacks anticipated blockchain technology and knew that something like NFTs would eventually arrive, he is shocked by the almost violent manner in which NFTs have stormed the art scene, practically overnight. “It’s probably the most disruptive thing that’s happened to the galleries since we opened 20 years ago,” he says over the phone.

Sacks worries that NFTs weaken digital artists’ (or their galleries’) control over how audiences experience their art. “That’s a major part of many artists’ vision for their work,” he says. “It needs to be shown on a certain size screen, or certain lighting is needed. We worked so hard for all of these details and specifics related to the experience. Many, many of those elements have been discarded for—you know—simple works that can be flipped very easily.”

While Sacks understands the lure of NFTs, or, at least, the appeal of owning something unique, he does not consider most of the computer-generated graphics being traded on OpenSea and other NFT platforms to be art. And who can blame him? The pieces that Sacks has purchased and promoted throughout the years, like Mark Napier’s The Waiting Room or Daniel Rozin’s Wooden Mirror, are fantastically complex works packed with meaning and history. They cause the viewer to marvel. A 24-pixel bear can’t possibly have that same effect.

But such misgivings don’t stop Sacks from using NFTs. In fact, their popularity has helped him sell more art. When it comes to collectors who really want to experience a work, Sacks has no issue handing them a paper of authenticity and minting an NFT. It’s not the blockchain technology that upsets him; it’s how it’s being used.

“There’s a fairly decent split between people buying NFTs and traditional media art collectors,” Sacks says. “Media art collectors are still interested in the work itself and how to live with it and how to experience it and how it impacts their life. And then there’s the NFT collectors who are collecting hundreds, maybe thousands, of these images and small videos. It’s just collectibles that are being used for trading and flipping, not necessarily for artistic enjoyment.”

He continues, “I mean, you’re basically buying things to put in a database and eventually sell, which is like acquiring stocks or different financial assets, and there is a danger to a larger population thinking that this is legitimate art.”

Adding to the danger is the rampant theft on marketplaces like OpenSea. Oddly, a technology that was developed to protect digital artists is the factor hurting them most frequently. While the blockchain proves ownership of an asset, nothing stops a person online from taking that asset, copying it, and minting another NFT of the copied image for themselves. Technically, that same image would live on two different blockchains. In the decentralized, freewheeling space that crypto loyalists champion, there isn’t an authoritative body to determine which NFT is the true original.

Often, marketplaces like DeviantArt will alert an artist to a potential theft by sending a message to the artist that contains images of a work that resembles their art. If the artist believes their work was stolen, they must show evidence to the platform selling the stolen art, proving that they are the original creator, and request that the copied work be removed from the site. The onus is always placed on the artist to prove that their work is authentic, not on the owner of the copied NFT. Most creators are willing to battle for their work, but when their pieces are being reminted across the web daily, it is nigh impossible to keep up.

After being notified by DeviantArt that his illustration of a minotaur had been reminted on another platform, Liam Sharp, a comic artist in England known for his fantasy art and work on DC Comics, took to Twitter: “Sadly I’m going to have to completely shut down my entire @DeviantArt gallery as people keep stealing my art and making NFTs. I can’t—and shouldn’t have to—report each one and make a case, which is consistently ignored. Sad and frustrating.”

Sharp’s announcement sent ripples through the NFT community. If revered artists could be ripped off and sent packing, how could budding artists expect to succeed? Weeks after that December 17 tweet, Sharp expanded on it in a somber 2,337-word Facebook post, stating that he’d decided to keep his DeviantArt gallery intact but refused to create more NFTs. He wished those staying in the NFT art space the best of luck. “It does seem that the beautiful open wilderness of freedom and exchange that the web once was has indeed been rendered a replica of our living world,” he wrote. “A place in which to sell, and game, to hack, and to fight.” Despite his frustrations with the darker side of the art form, Sharp said he was still “on the fence about NFTs” and urged his followers to keep an open mind.

Hold on for Dear Life

In a tea shop in Claremont, a college town known as the home of many artists in the California Scene Painting movement, I hop onto Discord, a communications app popular with gamers and the crypto community. Here, myriad chat rooms, called servers, buzz with the energy of a stock exchange floor. Users with names like ApeMama and Molm1 (anonymity is sacred in these spaces) swap information about the latest NFT series and predict how much they will make if their projects find celebrity backing. Sometimes, the chatter spills out of Discord and onto platforms like Instagram and Twitter, the latter of which now tells users to “show off the NFTs” they own “in a hex-shaped profile picture” by connecting their crypto wallets to their accounts. Anticipating a crash, NFT investor and crypto coach Tim Wheeler (@timtalkscrypto) tweeted a warning to his base on January 20 that was typical of the “heads up” posts in Discord: “US Congress holds a hearing tomorrow to discuss the environmental impact of #bitcoin. I expect extreme exaggeration. The truth: 40-70% of $BTC mining rigs run on renewable energy (estimated by @nytimes). Embrace the fear mongering. Be ready for dips. You know the drill.”

After being denied entry into most of the Discord servers (membership is typically reserved for NFT owners), I am surprised to be admitted into the Marine Marauderz server, which is managed by one of the NFT communities to which Chobanyan belongs. On their website, the Marauderz state that their mission is “to have amazing art, a vibrant community, and have a charitable impact!” While I am not yet convinced that the 2-D sharks are “amazing art,” the community aspect is bumping. When one member expresses concern that the value of Ether (the currency behind the blockchain that supports most NFTs) has fallen, a shiver of Marauderz immediately encourage the user to HODL, a mantra meaning “hold on for dear life.” The crypto veterans and NFT enthusiasts live by the HODL code. A soaring market, a crashing market, it makes no difference; they are in it for the long haul. If anyone mentions they’re considering selling their NFTs or leaving crypto altogether, especially someone new to the space, their fellow Discord community members chalk it up to FUD: fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

David Roberts, a professional race car driver and mixed martial arts fighter from the San Fernando Valley whom Chobanyan calls his “big brother,” is a major player in the NFT world, with assets in the highly expensive Bears Deluxe and CyberKongz editions. After learning about some NFT projects that had plummeted in value, Roberts tweeted, “This whole space is a rat filled casino. From now on, I am going to FUD all NFT people/projects. It’s not for people who don’t have money to lose. If you’re new, it’s inevitable that you get scammed or lose because of some rat. Initially, to find good projects, you must get fucked.”

In other words, getting suckered is just part of this new art market. To win big, one has to take it on the chin and keep swinging. NFT devotees do see themselves as entering an open wilderness of freedom. Thieves, scams, poor projects, and the environmental hazards posed by the insane amounts of energy used to keep the blockchain alive are simply temporary dangers that come with the territory.

Soon, they believe, when the metaverse arrives, HODL will pay off.

All Across the Metaverse

The strangest aspect of the metaverse is that in many ways it’s already arrived. Games like The Sims and Minecraft have been around for years and provide players with the freedom to explore worlds, construct cities, and interact with other users. Platforms like Second Life, Decentraland (a virtual world owned by its users), and the Sandbox, a blockchain-

based 3-D open-world space, push the envelope a bit further by allowing users to purchase land, build, and earn revenue from their investments—just like in real life. The only element missing from these virtual worlds is shareability. When users are able to hop seamlessly from one platform to the next and various cryptocurrencies can be used across different decentralized autonomous organizations, the metaverse will have fully manifested.

It may sound like a scene from Ready Player One, but companies like Facebook, Walmart, and Microsoft are gearing up for it. Facebook’s name change to Meta was more than an attempt to revamp the troubled company; it was a move to position it as a leader in the virtual world. Walmart is developing its own form of cryptocurrency that will allow users to shop in a virtual space for real-world and digital goods. And Microsoft just announced an attempt to acquire Activision Blizzard for nearly $70 billion, potentially giving the tech giant the means to develop virtual technologies and open-world games.

NFTs may figure prominently in the metaverse. In some instances, they will be the avatars that gamers use to explore virtual worlds, but for the most part, they’ll function like deeds to land or stock in businesses. A colleague of mine, a business reporter who covers cryptocurrency and wishes to stay anonymous, recently purchased an NFT that promises him part ownership in a casino set to open in the metaverse. Another friend, who is known online as PPK (the type of handgun used by James Bond), has acquired virtual land that he can sell to companies, like Gucci, that are seeking to build stores in these spaces. He has also purchased NFT weapons, like swords and bows, that can be resold for combat gaming. PPK has zero doubt that these investments will reap a profit.

“Our parents made truckloads off the stock market and real estate. But with the stock market at an all-time high and real estate that’s practically impossible to buy, what are we supposed to invest in?” he asks. “Investing in cryptocurrency and NFTs is like our real estate or gold. It’s better than gold.”

FUD or Future?

The big question looming over NFTs is their longevity. Some argue that the bloated prices cannot conceivably be sustained; others point to how much they have already become intertwined with art and other products, suggesting they will set a new standard for demonstrating ownership. But art gallerist Sacks sees past the black-and-white outcomes.

“NFTs will definitely stay around, but paying millions of dollars for some of these things is a bit exaggerated,” he says. “I think the values will be adjusted to what the real value is, but the NFT as a concept—as a contract that is potentially secured on the blockchain—is a brilliant concept and will be applied to many things.”

He adds, “Art will certainly continue to utilize them. My only hope is that there will be more education about NFTs and how they can be used for serious work.”

Considering the momentum behind NFTs and the many ways art can be made and interpreted, it seems that Sacks is onto something. Jack Dorsey, former CEO of Twitter, is working on ways to mint NFTs for music, and authors are considering how they can be used for owning literature in the virtual world.

Besides handling the $69 million sale of Beeple’s work, auction house Christie’s weighed in on the future of NFTs on its website: “Within our own industry, NFTs make it possible to assign value to the ownership of digital art, which opens the door to a sea of possibilities for a medium that is unbridled by physical limitations. As such, NFTs are paving a new way forward for the digital art market.”

This statement about “a new way forward” seems to encompass the high-quality art that a gallery owner like Sacks would sell, the bizarre visions that Beeple produces, and the pixelated creatures that promise riches in the metaverse. It’s evidence that virtual worlds have already changed ideas about what art is and how it is made and experienced.

ART WITHOUT ARTISTS

My friends, the business reporter and PPK, do not consider their NFTs to be art, but the overwhelming sentiment on Discord is that the good NFTs—the projects with fleshed-out backstories, detailed business plans, and eye-catching avatars—are as culturally relevant as anything in the Louvre. In these circles, it’s not ridiculous to expect that an NFT equivalent of the Mona Lisa could one day emerge.

Many avid NFT collectors are earnestly curious about other forms of art. Whether or not their NFTs sparked this interest, some, like Roberts, are passionate about their traditional, non-digital artworks. On his former Twitter account, Roberts claimed to be the world’s “Largest Collector of Russian Sots Art,” or Soviet pop art. When considering the artistic value of NFTs, he tweeted, “Art is about innovation. Digital art should be about innovation in its structure and code. The code is what makes the art that you see, the art factor of the asset is in the underlying coding. Cyberkongz is the Picasso, the Warhol, the Monet, the Francis Bacon of digital art.”

Roberts was seemingly suggesting that examining a CyberKongz NFT as one would appreciate a work by Bacon in a gallery is the wrong way of interacting with this new art form. To appreciate a digital asset that is randomly generated like the CyberKongz series is to marvel over the machine. If the code behind the series is solid, it should be able to churn out thousands of unique assets, each one an integral part of the world-building story being developed. In other words, to accept that computer-generated assets can be art is to accept that art can exist without artists.

Coming Soon

Wanting to experience the process of computer-generated art, I open an account on Wombo, an online app that allows users to produce creative images, or “dream art,” by inputting several word prompts into an empty form field that the software uses to create a composite from thousands of online searches. The site’s tagline reads, “High-quality artwork created in seconds.”

Skeptical, I enter a few random words: “Mountain,” “Flower,” “Bride.” When asked to choose a filter, I opt for the Salvador Dalí option. Then I sit back, waiting to be disgusted by what Wombo spits out. When the image appears, it looks like a woman’s head swirled into pools of reds and bronze streaks. Near the bottom, something resembling shadows of flowers or cave drawings dances toward the center. I am neither impressed nor repulsed by the image. I wonder what will happen if I actually attempt to capture a mood or a memory with the word prompts.

I enter a few more phrases and enjoy the results. After several more rounds, I try to resurrect the feeling of an evening from my childhood when I watched a Hollywood classic with my grandmother in her Los Angeles home: “Ten Commandments,” “Yellow,” “Soup.” I choose No Filter.

Seconds later, the finished image hits me like a chop in the throat. It feels as if that evening had melted and then coalesced on my screen. It’s exactly what I wanted to convey (or at least I convince myself of that). While not a Rembrandt, the image, which I title Yellow Sinai, certainly possesses the qualities of an artwork.

Before logging off, I spot an option that reads, “Mint as NFT, COMING SOON!”

Somehow, with the dream art still pixelating on my screen, the phrase “coming soon” sticks out. If NFTs generated by an algorithm can evoke this much of an emotional response, it’s not difficult to imagine how or why they would retain value in a strange digital land like the metaverse.

I cannot peel my eyeballs away from the screen, or that phrase, coming soon. It seems to say so much about so many things: More NFTs. The metaverse. A new way of experiencing art. It’s almost overwhelming.

So much is coming soon.•

Ajay Orona is an associate editor at Alta Journal. He earned a master’s degree from USC Annenberg’s School of Journalism in 2021 and was honored with an Outstanding Specialized Journalism (The Arts) Scholar Award. His writing has appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books, Ampersand, and GeekOut.