“I think it was my second day as a Christmas temp that this big woman came out and walked around with me as I delivered letters. What I mean by big was that her ass was big and her tits were big and that she was big in all the right places. She seemed a bit crazy but I kept looking at her body and I didn’t care.”

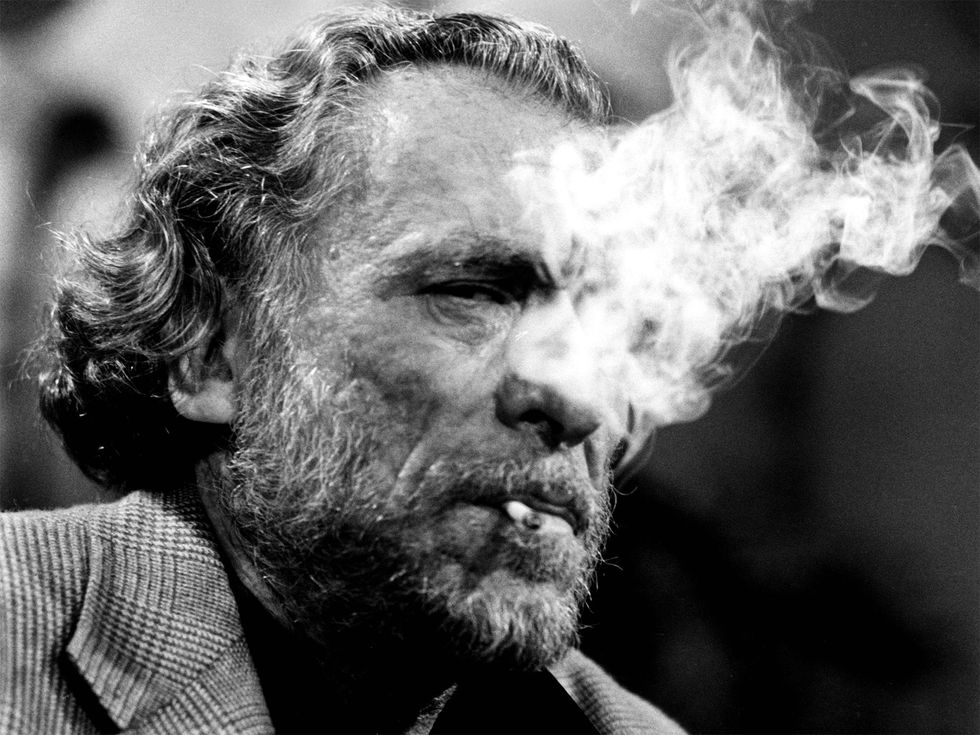

So writes Charles Bukowski in the opening chapter of his 1971 debut novel, Post Office. Today, it is unimaginable to think of an author so vulgar and baldly misogynist publishing anything like it. But Bukowski’s work—six novels, numerous short story collections, and more than 30 poetry collections—continues to be widely read 26 years after his death. It even attracts tourists to Los Angeles seeking traces of his life. I decided to join them and learn how they view this famous, yet problematic, writer.

The tour bus stops near the corner of Fifth and Los Angeles, in a section of downtown known as the Nickel. This tour, “Haunts of a Dirty Old Man: Charles Bukowski’s Los Angeles,” includes about a dozen sightseers—mostly middle-aged, mostly white, an equal number of men and women. We exit the bus and walk single file down Fifth Street around a woman pacing back and forth nervously, step by an older man muttering to himself, then pass assorted detritus on the sidewalk before entering the lobby of the King Edward Hotel, a relative oasis of calm.

“This is it,” tour leader Richard Schave tells us, gesturing toward peeling ceiling paint and faux marble columns as residents shuffle past us. Skid Row is still largely the Skid Row of Bukowski’s day, as if preserved for the benefit of wide-eyed tourists. “This is the life,” Schave says. “These are the people he was so interested in.”

Schave’s route also includes sites like Terminal Annex, where Bukowski worked for 14 years as a mail processor and on which he based Post Office, and the bungalow apartment on De Longpre Avenue where he lived from 1963 to 1972, which has been named a historical landmark, Bukowski Court, by the city’s Cultural Heritage Commission.

While making our way back to the bus after our Skid Row visit, I speak with a woman walking next to me. Her name is Zina Giannopoulou, and she’s a professor from Brentwood. She discovered Bukowski when she was a young girl living in Greece. “My father was very strict, so I found some kind of freedom reading [Bukowski],” she says. “I was learning English. I learned all these cool expressions and terms.”

I ask if she found Bukowski’s writing to be sexist. She shakes her head. “I found a side of myself that I hadn’t discovered before he came along,” she says. “It was a revelation.”

Outside Central Library, where Bukowski encountered the work of his hero, the writer John Fante, I approach two men with identical, chin-length curly brown hair: Trinidad Rivera, 33 years old, and his 19-year-old brother, Pablo, from Pasadena and Montebello, respectively. “The general consensus of society is: masculinity is toxic, so you need to stop being macho, being a man,” Trinidad says. “I personally believe that we do need to hold on to both the masculine and the feminine, so I would introduce something like this very masculine writer to my little brother and tell him, ‘Check this out, this is cool. If you like it, if you don’t, whatever, it’s all good. But I’m showing you this because I think this is important.’ ”

After the bus tour, I call John Dullaghan, director of the 2003 documentary Bukowski: Born into This. “I think Bukowski would’ve been on the side of the #MeToo folks,” Dullaghan explains. “I really do. Deep down, he was a very compassionate person, he was a very sensitive person, and he was always aligned with people who were struggling in their lives and who were criticized and demeaned just for being who they were.… He would’ve been down on people like Weinstein and Epstein.”

My quest also leads me to San Pedro, the small working-class community where Bukowski moved in 1978 and where he wrote his coming-of-age memoir Ham on Rye and his final poetry collections. He and his girlfriend Linda Lee Beighle, whom he’d marry in 1985, lived here until his death in 1994. But Schave’s bus tour doesn’t come here, and aside from some spray-painted stencil portraits and a small mural and quote from Bukowski in an alley behind a shuttered bookstore, there is little for Bukowski tourists to see. Angela Romero, a resident and local historian, wants to remedy this.

Last August, with the backing of arts and business leaders, Romero organized a $150,000 GoFundMe campaign for a bronze statue of Bukowski in downtown San Pedro. Six months into the campaign, just $11,670 has been raised. She tells me the monument has generally been well received—and yet, she acknowledges, times have changed. “Bukowski could not have become as widely popular had he been starting out right now, with the same work,” she says.

Bukowski, who would have turned 100 this August, lived nearly his entire life in L.A., and his love for the city and its most downtrodden residents remains as relevant as ever. If people focus only on his coarse and often demeaning language about women, Romero adds, they miss the point of his work. “It’s not the misogynist stuff that has made him timeless,” she says. “It’s the really profound stuff that talks about the beauty and the tragedy of life.”

Santi Elijah Holley is a writer and journalist based in Portland, Oregon.

Santi Elijah Holley is a Portland, Oregon-based writer, covering music, religion, history, and culture.