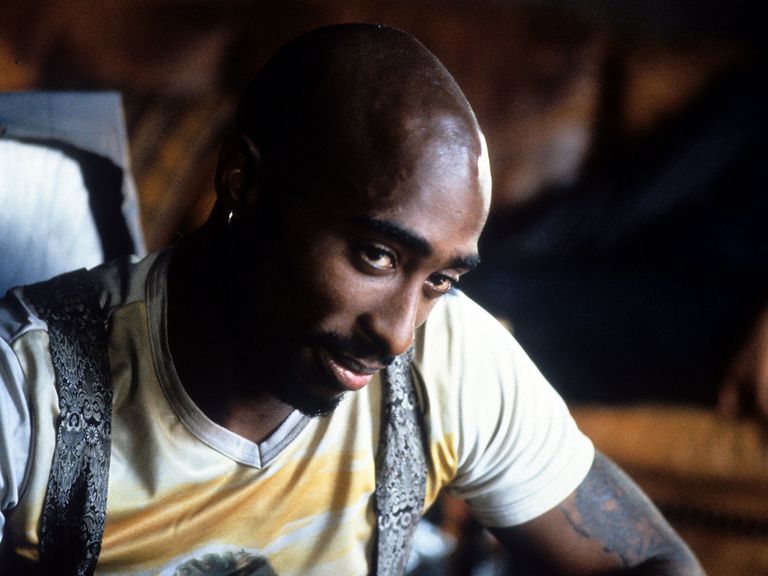

A long line of people extends outside the Canvas at L.A. Live, an event space in Downtown Los Angeles, on a sunny Friday in January. An equal mix of teenagers, millennials, parents, and grandparents, the predominately African American crowd rocks with excitement and anticipation. Many people wear Tupac Shakur T-shirts and other apparel, as though they’re about to attend a concert by the famous rapper. But Shakur, of course, has been dead for more than 25 years.

Today is the opening of the exhibit Tupac Shakur. Wake Me When I’m Free. It’s billed as a “fully immersive, thought-provoking experience” celebrating the late rapper and actor’s brief life and even briefer career. People have come here from all over the country, many of them traveling with their families in tow. Melody Robinson, 43 years old, came from Kansas City, Missouri, with her three grown children. “They got their own music, but they like Tupac, too, because they know he’s extraordinary,” she says.

Robinson’s 21-year-old son, Keith, goes even further. “I think he’s the best rapper in the world,” he says, notably using the present tense.

Even in death, Tupac Shakur has never stopped interesting and captivating fans young and old. If anything, this veneration has grown in the more than 25 years since his untimely passing. Shakur’s work is constantly reinterpreted, repackaged, and remixed, somehow managing to remain relevant to our quickly evolving times. Whether learning about his life story at this exhibit or through critical readings of his lyrics at universities as prestigious as Harvard or discovering and rediscovering his music, people are still trying to make sense of who Shakur was and what he stood for.

Tupac Amaru Shakur died on September 13, 1996, six days after being shot multiple times in a drive-by while stopped at a traffic light in Las Vegas. He was 25 years old. Shakur has now been dead longer than he was alive, but he continues to attract new generations of fans, many of whom, like Keith, weren’t yet alive when he was killed.

Shakur’s short and turbulent life has inspired multiple documentary films, a biopic, a Broadway show, numerous books, and any number of articles, essays, think pieces, college courses, and dissertations, in addition to the myriad conspiracy theories surrounding his murder. It’s fitting that his life is on display here, at a venue called Canvas. In many ways, that’s what his legacy has become: a canvas on which his fans project their hopes and fears to find meaning and draw comfort. His recording career lasted only five years, during which he released just four studio albums. By contrast, more than double the number of albums—including the Grammy-nominated, Diamond-certified Greatest Hits—have come out since his death, some of them selling better or otherwise charting higher than those he released during his life. In 2009, the Vatican added Shakur’s posthumous single “Changes” to its 12 Favorite Songs playlist on MySpace Music, alongside Mozart’s Don Giovanni and a recording by Pope Benedict XVI. In 2017, Shakur became the first solo rap artist to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Shakur, like Franz Kafka or Jesus, is arguably more famous in death than he was in life.

BLACK POWER AND THUG LIFE

Though Shakur was born in New York City in 1971 and attended high school in Baltimore, where he studied acting at the Baltimore School for the Arts, he is today best associated with the sun, surf, and drop-tops of the West Coast. In 1988, he and his younger sister Sekyiwa moved from Baltimore to the small Northern California community of Marin City, where the teenage Shakur struggled with poverty, hostility from his peers, and his mother’s drug addiction, an experience he documented in his single “Dear Mama.” He’d already been rapping and performing for much of his young life, beginning in Baltimore, and he continued in Marin City with a little-noticed rap crew called Strictly Dope. His break came in 1989, when he met 26-year-old youth advocate and poetry teacher Leila Steinberg, who became his first manager and helped facilitate the fateful meeting between Shakur and Gregory Edward “Shock G” Jacobs, the leader of Oakland-based party-rap group Digital Underground. Jacobs agreed to take the hungry and energetic rapper on tour with the group as a roadie, dancer, and hype man. Shakur was eventually given his own verse on Digital Underground’s 1991 single “Same Song,” which he followed later that year with a debut solo album on Interscope Records, 2Pacalypse Now, and the next year with his first movie role, in the Ernest R. Dickerson drama Juice.

This article appears in the Spring 2022 issue of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

It was around this time, as Shakur embarked on his journey into superstardom, that the line between the authentic person and the public perception of that person became blurred. For the rest of his life, Shakur generated conflicting opinions as to who he was, what he believed, and what he represented. Was Tupac Shakur an advocate for Black Power and racial pride, or was he merely a gangsta rapper who spouted about a thug lifestyle? Did people understand that the acronym THUG LIFE denoted “The Hate U Give Little Infants Fucks Everybody” (which inspired author Angie Thomas’s popular 2017 young adult novel, The Hate U Give, and the 2018 film adaptation)? Did his lyrics speak of revolution and societal change or of materialism and misogyny? Could he embody all of it at the same time, without compromising any of it? Fans and critics are still grappling with these questions more than 25 years after his death, and these ambiguities contribute to his enduring appeal.

Shakur’s stepbrother, Mopreme, performed and toured with him throughout his career and was part of his Thug Life rap collective. He believes that people are passionately drawn to his late brother because of his sincerity. “When Pac said something, you believed him,” Mopreme says. “You heard him, you believed him, you believed that he cared about you. You believed that he was commiserating with you. You believed he was gonna ride with you. He made you feel and believe that. He was a real dude.”

“He was the first rap artist that did a ‘Dear Mama’ or a ‘Brenda’s Got a Baby,’ that was able to articulate—not from a political place but from an emotional place,” says his teacher Steinberg, explaining why, as she sees it, Shakur connected so deeply with listeners. “Public Enemy gave you politics and Black activism; they were in your face. Tupac made you feel the pain of a young Black child. He made you feel the pain of abandonment. He made you feel the pain of forgiveness. That was different. He was an emotional artist that gave us anthems that we don’t let go of.”

Inside Wake Me When I’m Free, artifacts of Shakur’s life are displayed throughout multiple rooms, each room representing a different moment in his life and career. Walls are covered with handwritten lyrics, poetry, letters, photographs, and dozens upon dozens of personal notebooks, displayed behind glass cases like fragile artwork. Additional cases house rare memorabilia, from Shakur’s clothing and other personal items to movie props and scripts. Music, interviews, and other recordings play through headphones given to visitors upon their arrival. Different from a traditional museum show, this is a hybrid of a gallery installation and multisensory event, allowing fans to interact with Shakur on a more intimate level. Also unlike other so-called immersive experiences, such as the traveling multimedia Van Gogh and Picasso shows—which can feel like little more than standing inside a giant screen saver—this exhibit provides history and context to situate Shakur’s art in the present day.

Of course, any artist whose work was created years ago, whether two dozen or two hundred, is at risk of being misinterpreted or exploited for crass commodification. Shakur, especially, has been subject to both regrettable fates. He’s been marketed and peddled in any number of ways to any number of audiences, from a Tupac hologram projection at the 2012 Coachella music festival to the more recent announcement of the Immortal Collection, a series of NFTs inspired by his jewelry. With Wake Me When I’m Free, creative director Jeremy Hodges and curator Nwaka Onwusa, in collaboration with Shakur’s estate, seek to create a new narrative, reintroducing Tupac Shakur in the Black Lives Matter era.

Shakur’s songs often addressed difficult and noncommercial subjects like poverty, child pregnancy, systemic racism, and police brutality. He’d inherited his Black Power sensibilities from his mother, Afeni, a former member of one of the Black Panther Party’s New York City chapters (the late Afeni is given her own tribute in Wake Me When I’m Free). It’s those principles in particular that the exhibit as well as today’s students and scholars are taking another look at, hoping to connect Shakur’s lyrics to present-day conversations about racial reckoning and wealth inequality. If he were still alive today, how would Shakur—who in 1992 sang, “Although it seems heaven-sent / We ain’t ready to see a Black president”—feel about the historic presidency of Barack Obama? On the one hand, we’ve now seen both a Black president and a Black vice president; on the other hand, we’ve seen the killing of Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and so many others, as well as the presidency of a man who openly courted white supremacists. Reading Shakur’s words and listening to him—he offered an impassioned condemnation of income disparity during an interview on MTV—it’s reasonable to believe that if he were still alive, he would have plenty to say about the ever-expanding wealth gap. But a bullet from a .40-caliber Glock ensured that we would never hear him again.

DESTINY FULFILLED

Today’s Shakur fans and apologists are arguably just as loyal as they were when he was alive and creating new work and generating controversy; their devotion may even have intensified. His name may no longer top music charts, adorn movie marquees, or appear on magazine covers, but it’s no less marketable than it was at the height of his fame, as attested by the millions of monthly Spotify streams, the bestselling books, and the scores of people jammed shoulder to shoulder inside this exhibit.

Mopreme says that he and Tupac worked tirelessly “to help him be seen, so people could see his genius and how special he was.” According to Mopreme, Shakur always knew he was destined for stardom. “He knew he was a legend,” he continues, “and it’s good to see that the people recognize the young god.”

Born and raised in Los Angeles, 34-year-old Marlon Briscoe moved to Dallas five years ago, but he and his family have returned to visit the exhibit. “He’s always been an icon in our family,” Briscoe says. “His lyrics hold up still to this day. That’s what it is—you can listen to it, and it feels like he made this now.”

Briscoe and many others in attendance seem to share this feeling. Above all, their being here is a manifestation of the widely held desire to reflect on not just who Shakur was but also who he might’ve become. Shakur spoke to the least fortunate among us, the most troubled. Our collective need for someone to speak for us, to advocate for us and empathize with our pain, is eternal.

“He did a lot in his time here, and I think that’s what people hold on to,” Briscoe continues. “We didn’t get to see him in his 50s. We got him at such a young age, and he was so smart and just somewhere else already.”

For Steinberg, who watched Shakur develop from a young, penniless, and aspiring rapper into an international star, an icon, and, ultimately, a martyr, his enduring appeal goes beyond just his talent. “I don’t care if you’re from poverty or privilege, where you come from—all of us have damaged parts, and many of us don’t know how to manage our pain,” she says. “Tupac was constantly emoting. He cried for everyone. He gave us songs that helped us cry. We need that, because we struggle with our emotional development, and when you have an artist that’s so raw—he’s processing out loud in real time for you—we latch on to that…. He was such a bright light with so much possibility.”

And for his growing number of fans, he still is. •

Santi Elijah Holley is an award-winning journalist and the author of An Amerikan Family: The Shakurs and the Nation They Created. He is a regular contributor to Alta Journal.