On a smoky day last fall, a small party of aging males huffed and puffed its way up above 12,000 feet in the White Mountains, near the California-Nevada border. The winds were strong, and the summit zone—think of the treeless Tibetan Plateau, minus yaks—was seriously cold. The leader of our little expedition, Robert Bettinger, a UC Davis anthropology professor emeritus, carried an ice ax as he meandered up. No reason to hurry, his slouching pace seemed to say, but keep an eye out: there are interesting things all over this ground.

Bettinger should know. Forty-nine years ago, he began exploring in the Whites, looking for signs of prehistoric human presence. The idea that ancient hunters had come up high, tracking mountain sheep, was plausible, but Bettinger looked harder and longer than his peers might have, finding strong evidence to support the hunch. “I looked in places other people didn’t want to look” is how he explains it. Eventually, he found not just the signs of hunting trips but the remains of whole villages, sites where families had come to live for a while, venturing into the mountains as soon as the snows melted out in summer. The discovery of this intermittent use, which continued for over a thousand years, went against conventional wisdom about hunter-gatherers: why make the trip to the nosebleed zone, bringing your vulnerable women and children, when you could stay down in the Owens Valley, fishing and hunting and harvesting berries and roots and maybe even lolling in the local hot springs on occasion?

This article appears in the Fall 2021 issue of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

“No one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude,” Hemingway writes in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” He’s referring to the corpse of a big cat found at 19,710 feet in Africa. Bettinger may not have explained, to the satisfaction of all other anthropologists everywhere, what these ancient people were doing up so high, but that they were colonizing the really rugged places, gaining sustenance from a harsh alpine environment, is now no longer in doubt.

Bettinger stops on a patch of scrubby ground. He pooches his lips and lowers his head like a heron, poking at something with his ax. Loukas Barton and Micah Hale, two of his former grad students, now professional archaeologists, hang back expectantly. On the drive into the mountains this morning, the three of them talked shop the whole way, often exploding in laughter, using researcher jargon that I was too embarrassed to ask them to explain. I was the writer, after all; I was supposed to know something. I’d become interested in Bettinger because of a late-onset

fascination with western hunter-gatherers. This led to a lot of wandering around in obscure badlands, often with a book in my pack, but only one of the books I read struck me as truly original (and deeply ambitious): Bettinger’s Orderly Anarchy: Sociopolitical Evolution in Aboriginal California, a career-crowning volume published in 2015. It takes as its subject the past 15,000 years in Native California and points east, attempting a grand synthesis of all the moving parts, all the social, political, and environmental changes over that vast sweep of time, somehow fitting everything into 10 very readable chapters.

Big books near the end of long careers often have a baggy feel, theories expanded to make room for everything, differences watered down. But Orderly Anarchy is bracingly argumentative, focused, and in touch with a wide range of recent research. Bettinger’s own digs over 50-plus years, in the Owens Valley and in the Whites, as well as in northern China, where he studied the origins of agriculture, serve as his foundation; he seems to be the kind of researcher on whom nothing is lost, who has read everybody and is quick to admire the good work of others but at the same time has been following his own path from the start, a little cranky at times, elbows out, wanting to tell the story his way.

He finds something. It’s a tiny obsidian point, smoky-black, the edges still super sharp. Obsidian, the volcanic glass, was the material of choice for arrowheads around here, a gift to the hunters in being easy to work and a gift to the archaeologists, too, in that moisture invades a chipped edge at a known rate, a certain number of microns per unit of time; the little shard in Bettinger’s hand is a sort of clock, one that began ticking a long, long time ago.

The color tells Bettinger where the piece came from, what obsidian quarry. Ahead of us stands a shattered volcanic crag. It’s about 60 feet high, and as soon as we get close enough, the wind dies away—we’re in the lee of the cliff now, protected from the gusts. Bettinger tells us to look at the ground. I see a lot of toaster-size rocks, also some prickly plants, nothing growing higher than my knees. Wait—there’s a pattern in the rocks. They’re arranged in circles, six or seven circles, each between 12 and 15 feet across. Barton and Hale already know about this place because it’s famous, because of their former teacher: it’s the highest-altitude prehistoric village site in North America, discovered by Bettinger and his team in 1984. The circles were the foundations for dwellings put up by people needing a place out of the wind, a place to cook in, sleep in, make love in—some of Bettinger’s villages may have been lovers’ camps, it has been proposed, where young couples ran off to be alone for a while.

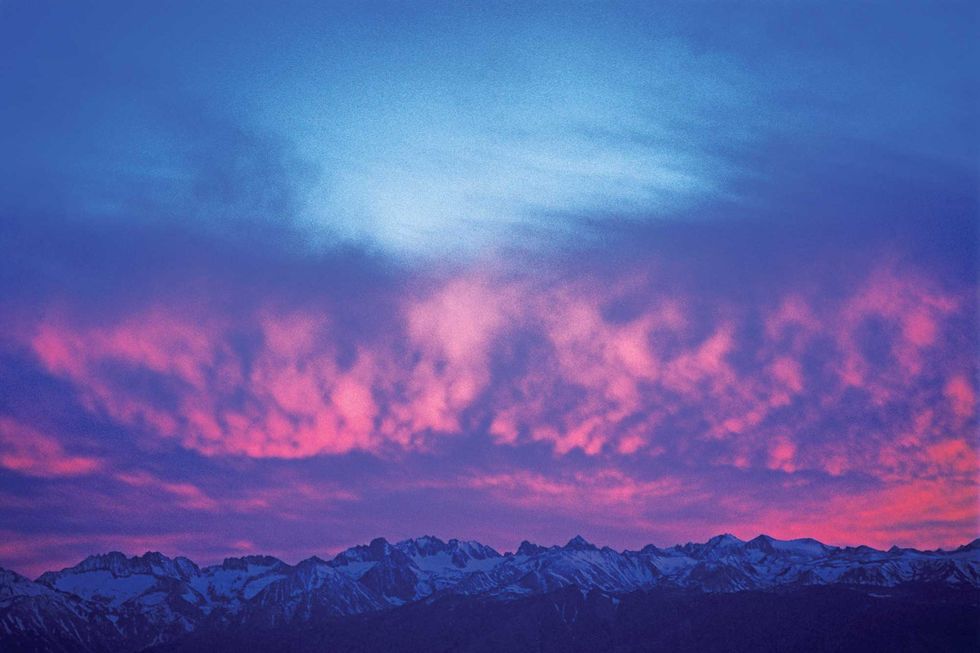

I have a sudden “ancientness” moment. I can see parties of prehistoric people coming up in the snow-melting-out season, finding this rocky, wind-protected spot over and over, their arrivals continuing for millennia. White Mountain Peak (14,252 feet) would have loomed over them, too—it’s just a few miles north of us, not a Matterhorn, not a great beauty, just a truly impressive dirt pile. Here mainly for the hunting, the ancient visitors would have supplemented their meat diet with roots dug in nearby meadows, gathering water at the springs and seeps. The spectral mountain light would have gotten into their heads, as it’s getting into mine. There’s just something about being up so high, a little closer to the stars and the clouds, on the lower edge of heaven; prophets and mystics have always come to mountaintops, seeking whatever it is that compels them, like Hemingway’s leopard. To the west of this spot, 30 miles away as the crow flies but seemingly right there, touchable, is the eastern front of the Sierra Nevada, some summits already snow-dusted. I wonder whether the villagers were into majestic views like this one or were too busy gathering calories—laying in a supply of mutton to carry back down the mountain—to philosophize. Bettinger, for all his wide-ranging scholarship, doesn’t much talk about that. As an evolutionary anthropologist, he’s after what can be backed up with evidence, solid material evidence—give him the leavings of a thousand ancient dinners, a pile of fossilized coprolites, shreds of old basketry, and chipped arrowheads, and he can tell you a great story. But as for the soul of ancient woman or man—if there is such a thing as the soul—he keeps quiet.

Bettinger is sun-toughened, tall, not overly gym-toned, a bit saggy. Some generations ago, he would have been identified as an “outdoorsman,” a type often found among the eccentric dads in some neighborhoods, a fisherman or a deer hunter, not a tree hugger, not a neo–John Muir, just someone happy outdoors, happy as hell. Born in Berkeley, he grew up in Belmont; his father was a PG&E engineer and a history buff, and the family took vacations in Humboldt County, on the Eel River, where his grandparents had a place. Bettinger liked the woods and rivers a lot. “My life is still keyed around fishing for steelhead every year,” he says. These days, he has a cabin on the Klamath, within the historic territory of the Karuk Tribe.

Orderly Anarchy begins with Ishi, the “last wild Indian” in America, as he has been called, who was taken into custody by white people in August 1911. Ishi’s band of Yahi people subsisted for several decades after the Three Knolls Massacre of 1865, wresting a living out of a territory east of Chico. This was not a new problem, surviving in the hills; it was the basic California lifeway, California being the world homeland of hunting and gathering. By the time the first Spanish missions were being built, in the late 18th century, the highest population density of hunter-gatherers ever known anywhere was in California. In other parts of North America, meanwhile, agriculture had superseded this supposedly primitive practice. Just as there’s a lot of headshaking today about the crazy way people live on the West Coast, what with the wildfires and the earthquakes and everything, scholars thought of California as a puzzling exception, hard to explain unless you believed in the inborn backwardness of the people.

California was ideal for agriculture, of course. Well watered by many rivers, its soil was some of the richest in the world. And tribes did experiment with growing corn. But, on the whole, farming failed to win many people over. As a sustenance model, it was simply less reliable. Anthropologists like Bettinger look for lawful explanations of such outcomes; it can’t just be that the people were lazy, that they didn’t relish lives of hoeing, weeding, and parched corn for dinner. Hunting and gathering required lots of labor too. Bettinger has taken a close look at that, at what the work was like and who did most of it—the women—and how the burden changed over time.

On our drive up today, we passed through a giant valley at about 11,500 feet. Bettinger pointed out a grassy area below us. Near it was a hunters’ camp that he and his students had found, “25 square meters where people came for over 5,000 years.” The camp was close to paths that mountain sheep followed up from the lowlands. Hunters would build blinds, then ambush the sheep when they meandered through.

“We found lots of points,” Bettinger said. “It was a group hunting place, therefore chaotic. When the bow first appeared, around 450 AD, guys could go out by themselves, not in groups, and then you don’t have lots of missing points, because each guy keeps track of his shots.”

I was confused. Hadn’t there always been bows and arrows? No, there hadn’t, it turned out. The bow was “surely present throughout the Old World by 8,000 B.C.,” Bettinger writes in his book, but it showed up in the New World later. Before it arrived, there was the atlatl, and before that, the spear, both less accurate. A bowhunter, out on his own, could dependably bring home at least a couple of tasty rabbits, while hunters in groups went after bigger game and often failed to get any.

Bettinger shows the social effects of this move toward solo hunting. He also tracks the impact of another new device, the seed beater, which came into use in about AD 800. It heralded more intensive harvesting of wild seeds, the women now able to winnow more efficiently. Starvation became less commonplace. With more babies making it into adulthood, the population increased. In the Owens Valley, it had been static for the previous 10,000 years; then, between AD 450 and 1250, it tripled, doubling again between 1250 and 1750.

Predictably, people began to move, to migrate. In time, the Numic people—speakers of any of a group of closely related languages, Paiute and Shoshone among them—came to occupy an enormous area: most of Nevada plus parts of Utah, Oregon, Idaho, and Wyoming. They crossed the Rockies and spilled down the other side, into the Great Plains. In their wanderings over many centuries, sometimes they came upon the ruins of great corn-grower complexes—Mesa Verde, the magnificent cliff dwelling in southwest Colorado, was probably empty by the time they showed up, its once-thriving agricultural world now utterly gone. As Bettinger writes, “the ruins of Mesa Verde were now in the hands of…the Ute, a Numic-speaking people recently arrived from Eastern California.” The Ute’s sustenance model had not failed them, as agriculture had failed the Ancestral Puebloans; over time, the Numic people had developed an ability to survive in virtually any kind of terrain, from lowland desert to snowy mountaintop, which allowed them to explore at will.

Leaving the wind-protected village site, we come to a scrubby hill where Bettinger pokes around with his ice ax some more, soon turning up a small, flat stone. It’s a milling stone, he tells us. Ricegrass grows here, and the seeds were crushed using such stones. Bettinger finds another stone, then another. I find one too, I think, but it’s the wrong kind of rock: too soft.

The night before, in the backyard of my motel in Bishop, the Elms, I got Bettinger talking about acorns. Acorns were eaten west of the Sierra for thousands of years, but only in the intensification period—when the importance of big-game hunting decreased even as gathering efforts resulted in more food per capita, beginning about 1,500 years ago—did people get serious about using them as a staple. (The staple farther east was the pine nut.) “The Hupa word for human is ‘acorn eater,’ ” said Bettinger, repeating something I thought I already knew—probably I read it in his book. “Working out the process of how to leach out the tannins took a lot of ingenuity, but the real breakthrough was social, because you had to be able to secure this stuff from other people…. Guys would steal it off you, all your nicely ground-up and leached-out acorns…. There was a freeloader problem, too, guys in your own group who’d hide out while the processing got done, then show up for meals. The bow makes it easier to protect your stuff from thieves, but you can’t be shooting your own guys…. They had to make a leap; there had to be a new idea, privatization—that you could keep the stuff you collected for yourself, you and your family.”

Before this change, most food went into a communal kitty. This sounds like a good basic system, but in practice, people were disinclined to gather and hunt if those who had done no work also had a claim on the goods. The crucial part of Bettinger’s book is about changes in custom, in daily practice, evolution being driven not so much by new tools like the bow and the seed beater as by new ideas, new legal and economic doctrines, some of them straight out of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. Bettinger is masterful in developing this argument step-by-step, giving due attention to the large variety of cultural practices in precontact California, 78 distinct languages, hundreds of different social groupings going their own way in countless insular little Edens, territories large enough to provide a good living but small enough to defend against others. Groups often despised and feared their closest neighbors but got together with them to trade; trade was a useful and exciting thing, potentially profitable, giving access to goods that you didn’t produce yourself.

At this point, we were joined by Gordon Wiltsie, who would be taking photos the next day when we went up into the mountains. I’d never met Wiltsie before—I knew him only by reputation, as the greatest living photographer of the High Sierra. After accepting a beer, he got right down to it with Bettinger, posing a question that I’d been too reluctant to ask myself: “What’s your evidence for the private-property innovation that you say was so important? Was it something you dug up, some kind of new artifact?”

Missing not a beat, Bettinger replied, “No, it’s the ethnography. What the old people told us about the old days. Professors sent their grad students out to get the story before the elders all died, and this is what they told us.”

I was flabbergasted. Somehow I’d assumed that Bettinger had dug up something solid, some new type of grinding stone, maybe, with the words “for privatization purposes” printed on the back.

Seeing my perplexity, he said, “Just read the ethnographic accounts. The Numic people reported this over and over. It’s something they all knew about.”

“But how do you know the old people hadn’t borrowed the white man’s ideology,” I said, and “didn’t begin talking about private property and individual rights and things like that because the Americans were talking it up, lecturing on the sanctity of private property while grabbing everything the Native people had?”

Bettinger was silent for a moment. Then, “Just read the accounts. It’s not some borrowed idea; it’s their idea. They didn’t get it from us; it came out of this hunter-gatherer world, before we ever came along.”

This new idea drove a large social change in the thousand years before European contact. Tribes devolved into subtribes and tribelets, into clans that descended from a single male ancestor, into single families living on their own. Here’s where Bettinger’s idea of orderly anarchy comes in. This minutely divided world was not chaotic, not anarchic in the usual sense of the word. Nor was it beset by violence and war; there were outbreaks of conflict, but warfare in California was usually on a small scale and not long-lasting. Nothing like the Iroquois Confederacy or the Aztec Empire ever arose in California. Some “big man” cultures appeared here and there, with class differences and dynastic inheritance of power and wealth, but overall the tendency was toward a kind of rough egalitarianism.

A kind of paradise, then, if you’re of a libertarian bent. A self-governing, pretty peaceful world that gave birth to a benign form of early capitalism. Bettinger is not a proponent of early or late capitalism, particularly, but the image of a rich human world, culturally complicated, nonhierarchical, and for many centuries able to provide well for most of its people, arises on its own from his writings. The long enduring of that world was not an accident: the “hunter-gatherer systems of California were…multiply evolving,” he said, continually outpacing agriculture, which, like all living systems, was itself evolving—not outpacing it forever, though, because nothing is forever, but outpacing it for a great span of time.

The night after our day in the mountains, we find ourselves back at my motel, again drinking beer in the cold backyard. Under the influence of my second bottle, I can see it all: a tiny band of hunter-gatherers from around Bishop swelling crazily in number as they finally get enough to eat, spreading out quickly to the north, east, and southeast, in time colonizing the whole Intermountain West, traveling on foot until they somehow evolve into the horseback-riding, tepee-dwelling Comanche. Meanwhile, in California west of the Sierra, a world of hundreds of touchy little tribelets resists the spread of agriculture by being too robust, too successful. In both cases, innovations in the getting and owning of food—acorns, seeds, pine nuts, rabbit, venison—drive the process. Without “intensification,” probably neither thing happens.

A great thought edifice, a large, well-integrated theory, stands on thousands of small, in-the-weeds discoveries, it occurs to me. When I mention to Bettinger that there’s a kind of Rube Goldberg–machine quality to his work, he laughs and says, “I believe most of what I maintain as anthropological truth.”

For some reason, I think of Bettinger’s grandfather, the one on the Eel River. He and his wife lived on 20 acres, Bettinger told me in an email, without running water or electricity for years, and he was “deeply interested in Native American lifeways—he knew about aboriginal burning before it was cool.” Sometimes he unearthed artifacts on his land. You can see how archaeology might have been in the cards for Bettinger from the start. But “archaeology is boring,” he likes to say, meaning the hard, repetitive work of excavating; what he liked better was surveying, setting forth on new ground, alert to its botany, zoology, hydrology, and all the rest. California’s hunter-gatherers did the same type of thing. They exercised a similar extreme alertness, to judge by the use they made of wherever they found themselves. “Once they had figured out the alpine zone,” Bettinger has said, “they could move anywhere,” colonize virtually anything. But that wasn’t why they went up high in the Whites, I don’t think—to work on their skills. No, I’m betting on those lovers’ camps, with those excellent views across the valley.•