In 2020, an elected panel in San Anselmo, a 12,000-person town in Marin County, voted to remove Sir Francis Drake’s name on a high school because of his involvement in the slave trade. The following year, in May, the school board replaced the famed English explorer’s name with that of Archie Williams, a Black runner who won Olympic gold in Berlin alongside Jesse Owens, served with the Tuskegee Airmen, and taught at the school for more than 20 years. A letter from the superintendent informed parents that the board was trying to make the school “more anti-racist,” and that the current name did not “align with this goal and our values.” Nearby, local officials also took down a 30-year-old statue depicting Drake at the Larkspur Ferry Terminal. Quite a comeuppance for a man who claimed that Indigenous inhabitants along the Pacific coast believed he was a god when he first came ashore, in 1579, after which (again, in his view) they handed over their land to England.

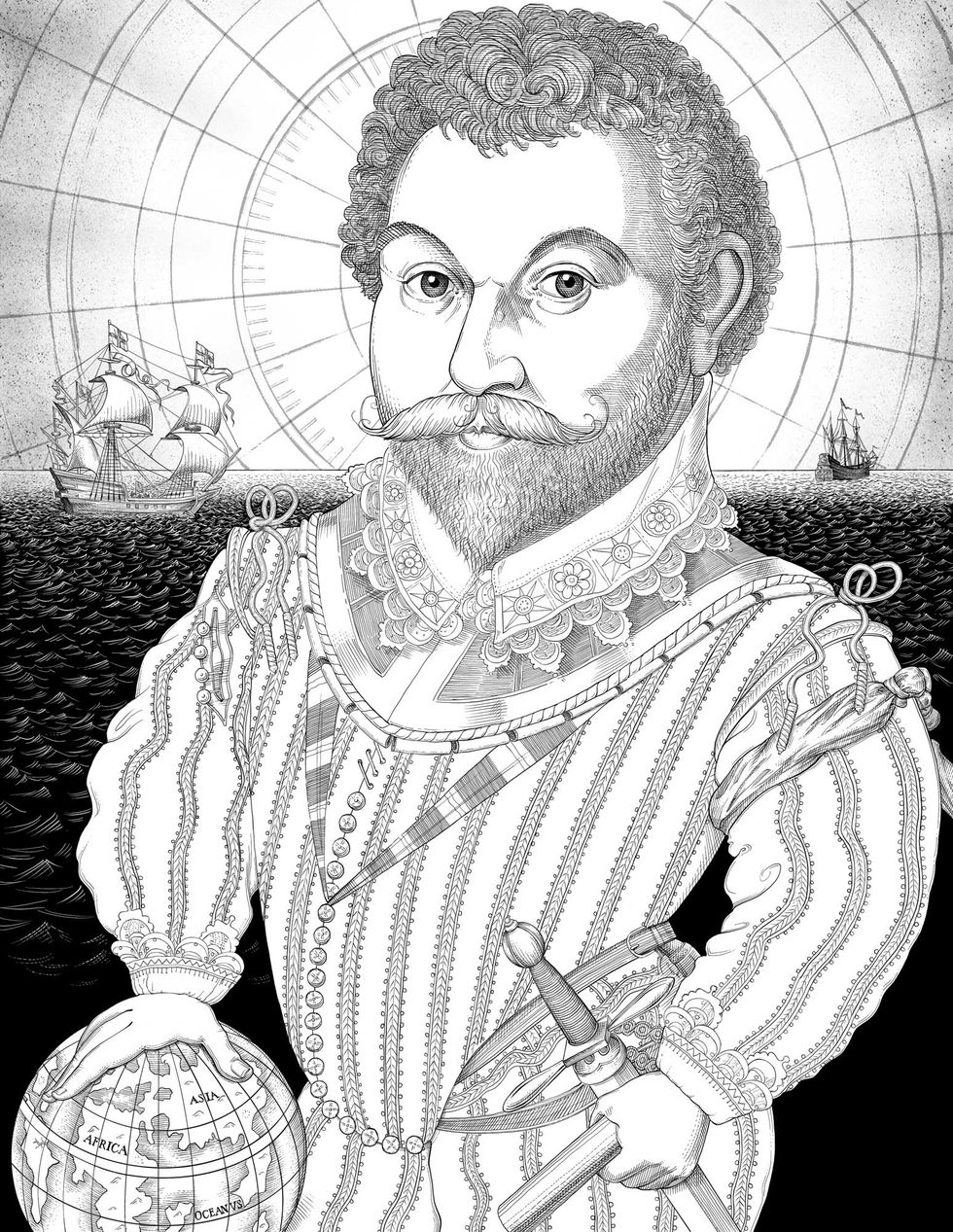

Just five years earlier, in 2016, the National Park Service erected a plaque dedicated to Drake at Limantour Beach, about 26 miles west of San Anselmo. It recognized the area as the Drakes Bay National Historic and Archaeological District, marking the spot where he perhaps first landed on the West Coast (though no one knows for certain whether he ever set foot in California—more on that later). The park service’s act was the latest in a long line of efforts in the area to honor Drake, who, in addition to being the first of his nation to reach the Pacific coast, led the second circumnavigation of the globe. In 1892—while Chicago was preparing to mark the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s first voyage with a massive international commemoration—an Episcopalian bishop erected a wooden cross to celebrate Drake near Chimney Rock on Point Reyes. Two years later, the church constructed a large sandstone Celtic cross, which still stands in Golden Gate Park, to mark what it claimed was the first Protestant sermon delivered in North America, by Francis Fletcher, a chaplain of Drake’s. Another wave of Drake adulation arrived in the 1910s and ’20s, just as cities across the South were erecting statues to honor Confederate generals. San Francisco’s magisterial Sir Francis Drake Hotel opened off Union Square in 1928. The Drake Navigators Guild launched in 1949, eventually enlisting renowned World War II fleet admiral Chester Nimitz as its honorary chair to support efforts to identify Drake’s landing spot.

The battle over public symbols of long-dead historic figures has been most intense in the South, where defenders of the so-called Lost Cause have tried to prevent the toppling of Confederate monuments. But California has reckoned with its past too. Columbus got his own comeuppance when, in 2020, San Francisco removed a statue of him at Coit Tower and state officials took down another (in which he was depicted with Queen Isabella) at the capitol in Sacramento, where it had stood since 1883. Protesters tore down statues of Junípero Serra, the 18th-century creator of the state’s Catholic mission system, for his subjection of Indigenous people to deplorable treatment. And the UC Hastings Law board of directors, faced with damning evidence about the role the San Francisco school’s 19th-century namesake played in the genocide of Native people, agreed to take his name off the school. Some activists who wanted the San Anselmo school renamed mentioned the 2020 murder of George Floyd, which sparked racial justice protests across the country, as one factor in their push for the change.

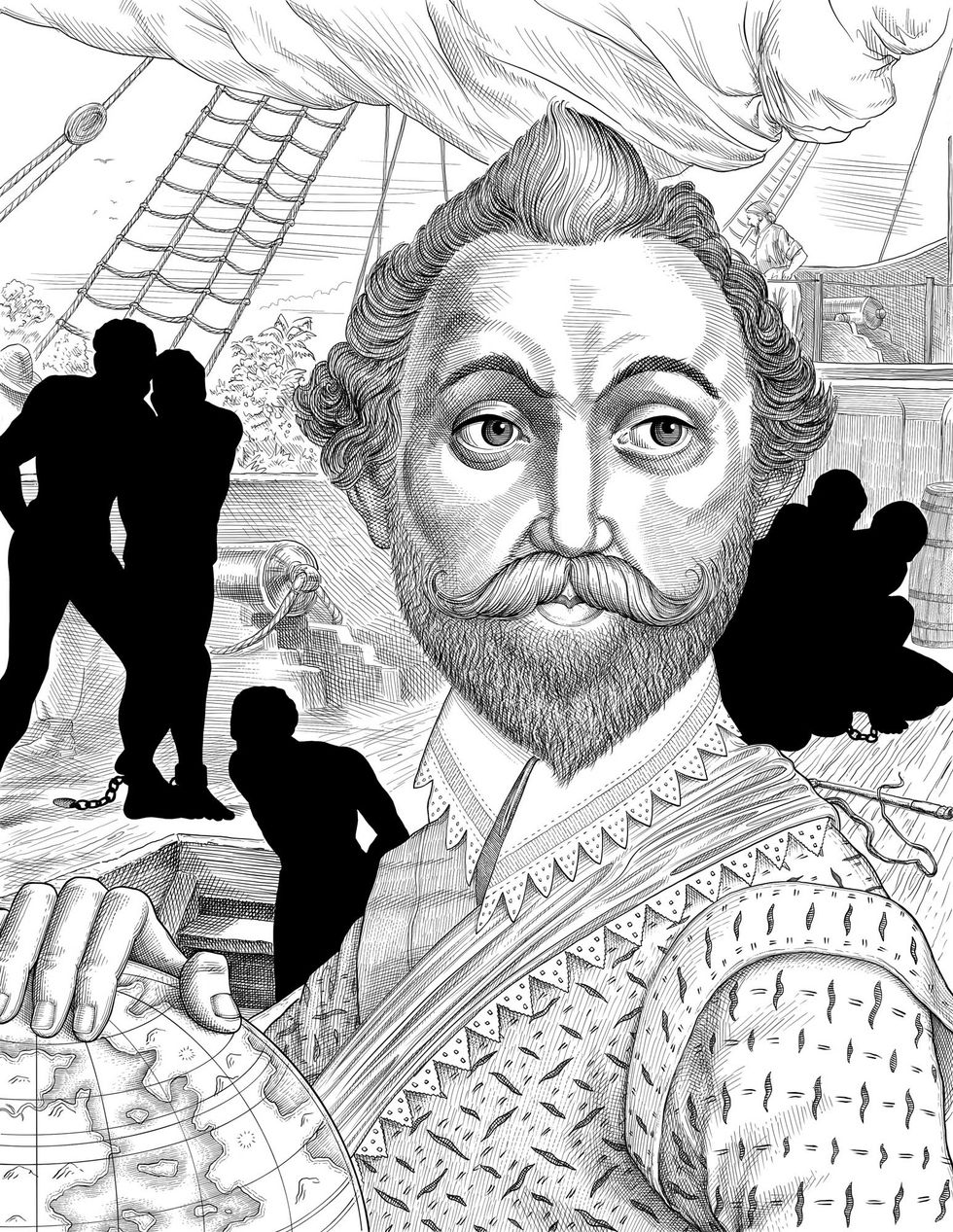

Tensions in California haven’t resulted in violence by white supremacists, as they did in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 during the dispute over a statue of Robert E. Lee. Still, debate rages here, too, even though the facts are not in dispute. As a young man, Drake played an active role in the subjugation of African people. The explorer’s supporters in California have long separated the actions of Drake the young slave trader from those of Drake the explorer (or just ignored the former). Unlike Serra and Hastings, Drake committed his crimes far from California. In the mid-1580s, according to fragmentary evidence, a then-older Drake quite possibly set free scores of enslaved Africans whom he’d captured from the Spanish and taken to the coast of modern-day North Carolina. Traces of such actions prompted one biographer to write in 2020 that “Drake stood up and demanded freedom and respect for Indians and blacks.”

This article appears in the Spring 2022 issue of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

However, these episodes in Drake’s life can’t be separated, either literally—his work in the slave trade was his break into international exploration—or figuratively. Drake’s beliefs that the Natives gave up their land and thought him divine were not just the stuff of racialist fever dreams. His visit to the Pacific coast enabled the English to justify continent-spanning North American claims that encouraged the conquest of Indigenous peoples, and this mindset thrived for generations. While many textbook histories focus on California after the Spanish took over the region, Drake still mattered. “The Spanish really did reshape the region in ways that continue to this very day,” says Steven Hackel, a renowned biographer of Serra. But Drake’s claim likely limited their efforts—almost 200 years passed between his landing and the spread of the mission system, even though the Spanish explored the coast earlier. Spaniards long accepted England’s ownership even though they reviled Drake.

Shortly before the plaque ceremony at Limantour Beach in 2016, Greg Sarris, the tribal chair of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, noted that studying Drake “will help all of us today navigate an increasingly complex and socially diverse world.” He also explained that when Drake arrived with forces from the sea, “our ancestors thought the dead were returning.” In some ways, they have.

POWER TRIP

In the summer of 1579, Drake landed to patch leaks on his galleon, the Golden Hind, initiating the first sustained contact between the English and any Indigenous group on the Pacific coast. On June 17, shortly after they put ashore, some local people came to meet him and his crew. If the English were indeed in modern Marin County, then the welcoming committee were likely Miwoks. As was the custom of many Indigenous groups across the continent, the residents offered hospitality and presents to their visitors. Drake reciprocated by giving them clothing to cover their nakedness, which offended his sensibilities, although not theirs. An Indigenous man the English called “a king” placed a feathered crown on Drake’s head, and Drake later claimed that this man, through sign language, gave the Natives’ land to the English. The explorer planned to take home the “riches & treasure” of the region to add to the burgeoning coffers of Queen Elizabeth I.

No one, including Drake, could have anticipated such an event for a boy born around 1540 in humble circumstances on a farm in the small Devon town of Tavistock. In the 1560s, Drake worked for John Hawkins, a mariner eager to enrich England by stealing enslaved Africans from imperial rivals, which pleased her majesty. This work led to more patriotic (and self-inflating) opportunities for Drake: stealing gold from the Spanish off Panama and, in 1575, assisting an English army as it slaughtered 500 men, women, and children on Rathlin Island, a bloody chapter in the queen’s conquest of Ireland.

In 1577, Drake accepted a commission from Elizabeth to lead five ships through the Strait of Magellan and northward along the Pacific coast in search of the western opening to the Northwest Passage, which the English explorer Martin Frobisher had claimed he’d entered from the Atlantic the previous year. Elizabeth also authorized Drake to ransack Spanish towns along the way, an order he pursued with relish.

After a harrowing journey, Drake had only one remaining ship—which he rechristened the Golden Hind—when he reached the Pacific. After a spring of “robbing, raping and murdering his way up the Pacific Coast,” as the Stanford historian Richard White recently described it, he sailed at least as far as Oregon. The Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius, the most renowned mapmaker of Drake’s era, believed the Golden Hind reached a latitude of 57 degrees north—somewhere along the coast of modern-day Alaska—before it reversed course and headed south toward its date with destiny.

As one chronicler of the voyage wrote, “it pleased God to send us into a faire and good Bay,” but beyond that, the ship’s account suggests that the English did not understand the local environment. They probably docked along shores boasting remarkable marine life but ignored them, even though describing the bounties of shorelines was a typical act of English travelers at the time. The author noted that the Natives wore deerskins and the hides of coneys, but the visitors had no way to learn more about the region’s abundant natural resources because they could only use improvised sign language to communicate.

In the days that followed, locals allowed the English to set up camp and brought them more gifts, including tobacco, which Drake would have known was a wonder drug capable of healing many human afflictions, besides providing pleasure to those who “drank” the smoke. The chronicler noted that “they supposed us to be gods, and would not be perswaded to the contrary.” The Natives greatly outnumbered the newcomers and could have killed them easily. Instead, they chose to lay down their bows and arrows and to treat the English with hospitality. Convinced that the Indigenous people considered them divine, Drake interpreted their hospitality as reverence. During the visit, community members sang and danced. Before they departed, Drake and his companions nailed an engraved plate with the queen’s name, and an English coin, to a post, noting the date and the fact that the local population had given its land to England. Then they left, bound for home via the Pacific.

In the 19th century, scores of investigators tried to pinpoint the exact location of Drake’s landing. Eventually, cartographers sprinkled his name around coastal Marin: Drakes Estero, Drakes Head, Drakes Bay. Enthusiasts sought, as White observed, to establish a Protestant and Anglo-Saxon origin story for the Golden State.

The ambiguous records left by Drake make it difficult to know where he landed. Truth be told, the English didn’t know where they were, a common problem for European explorers in the 16th century. The archaeologist Melissa Darby is the author of the 2019 book Thunder Go North: The Hunt for Sir Francis Drake’s Fair and Good Bay. She has scoured manuscripts and ethnographic evidence, and she recently told me that the “long-held theory that Drake was in California is unsupportable.” She is sure he landed in Oregon.

AN EXAGGERATED CLAIM

In 2019, the New York Times launched the 1619 Project to encourage Americans to reinterpret the country’s history through legacies of enslavement. What do we make of Drake in our era of reckoning with the past? Those who want to remove him from public view focus on his participation in the slave trade, which predated his journey to the Pacific coast. But what happened along California’s (or Oregon’s) shores provides clues to understanding the deeper past of the West—a past that deserves to be explored with the same amount of rigor as the makers of the 1619 Project applied to the rest of the country.

Where exactly Drake landed, the obsessive concern for generations, matters less than what he claimed. Did Drake truly believe that the Indigenous people gave the English their land and became Elizabeth’s willing subjects? The story is implausible and no doubt wrong. His claim was based on an ignorance and arrogance built into the ways in which European explorers understood the world.

Around the same time, other English sailors encountered Indigenous peoples in Nunavut, in Canada’s Arctic Archipelago; the Outer Banks of North Carolina; and, in the early 17th century, Maine and Jamestown, Virginia. None of the people in these places offered their lands or volunteered to become the subjects of a distant monarch. What Drake likely witnessed was an effort on the part of the Natives to create an alliance. Like other Indigenous people in the 16th century who met Europeans in the modern-day Americas, they probably wanted manufactured goods that the English had on board.

When Drake returned to England in 1580, crowds flocked to see the Golden Hind. Writers and artists rushed to proclaim his maritime feat. Amid the celebrations of the circumnavigation, his visit to the Pacific coast of North America garnered less attention. Yet, like the colonists in Jamestown who captured a Portuguese ship in 1619 and brought the first Africans to the Chesapeake, Drake contributed to the English conquest and colonization of North America. Removing his name or statue may fit current politics, but we need to understand his visit rather than erase him from our collective memory.

Drake’s legacy is far from settled. Just ask the school officials in San Anselmo. Archie Williams High School sits at 1327 Sir Francis Drake Boulevard.•

Peter C Mancall is the Andrew W Mellon Professor of the Humanities at the University of Southern California.