Researchers believe they have solved the nearly 700-year-old mystery of the origins of the Black Death, the deadliest pandemic in recorded history, which swept through Europe, Asia and north Africa in the mid-14th century.

At least tens of millions of people died when bubonic plague tore across the continents, probably by spreading along trade routes. Despite intense efforts to uncover the source of the outbreak, the lack of firm evidence has left the question open.

“We have basically located the origin in time and space, which is really remarkable,” said Prof Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. “We found not only the ancestor of the Black Death, but the ancestor of the majority of the plague strains that are circulating in the world today.”

The international team came together to work on the puzzle when Dr Philip Slavin, a historian at the University of Stirling, discovered evidence for a sudden surge in deaths in the late 1330s at two cemeteries near Lake Issyk-Kul in the north of modern-day Kyrgyzstan.

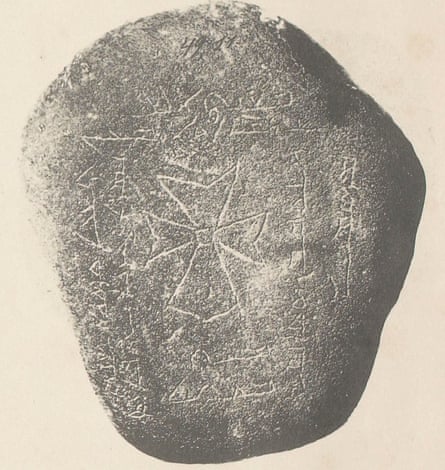

Among 467 tombstones dated between 1248 and 1345, Slavin traced a huge increase in deaths, with 118 stones dated 1338 or 1339. Inscriptions on some of the tombstones mentioned the cause of death as “mawtānā”, the Syriac language term for “pestilence”.

Further research revealed the sites had been excavated in the late 1880s, with about 30 skeletons removed from their graves. After studying the diaries of the excavations, Slavin and his colleagues traced some of the remains and linked them to particular tombstones at the cemeteries.

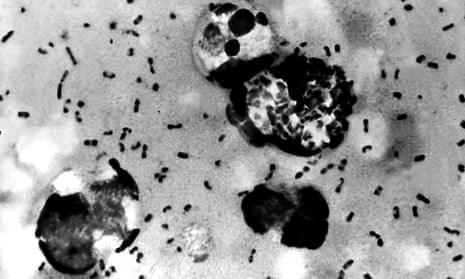

The investigation then passed over to specialists on ancient DNA, including Krause and Dr Maria Spyrou at the University of Tübingen in Germany. They extracted genetic material from the teeth of seven individuals who were buried at the cemeteries. Three of them contained DNA from Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes bubonic plague.

Full analysis of the bacterium’s genome found that it was a direct ancestor of the strain that caused the Black Death in Europe eight years later and, as a result, was probably the cause of death for more than half the population on the continent in the next decade or so.

The closest living relative of the strain was now found in rodents in the same region, the scientists said. While people still become infected with bubonic plague, better hygiene and less contact with rat fleas that can transmit the infection to humans have prevented further deadly plague pandemics.