What is it poets are for these days? Increasingly, in a world where brevity matters, verse makers are anywhere words are under pressure—which is everywhere. At school, in church, in the town square. It’s not an accident that Audre Lorde’s and Adrienne Rich’s lines decorate protest marches. Their poems were, after all, the record of revolutionary consciousness. Now, of course, the town square is online, too, where snapshots of powerful poems churn the world. Poets, not surprisingly, are good at Twitter, too. Giving a poet a 280-character restriction is like giving a dog a bone.

Not all poetry is public, though. In fact, even poetry addressed to us, toward us, the reader, depends on privacy. It depends on partial viewership, on interiority, on hour upon hour of time spent alone, out of which comes, perhaps, just one poem. In a world of hacking and constant drilling for social capital, the poet who can offer us the feeling of lived experience backlit by intimacy without giving (or demanding) everything—without selling us on his or her or their selves—is offering something so precious that the word luxury comes to mind. Were that word not so degraded by its attachment to goods alone.

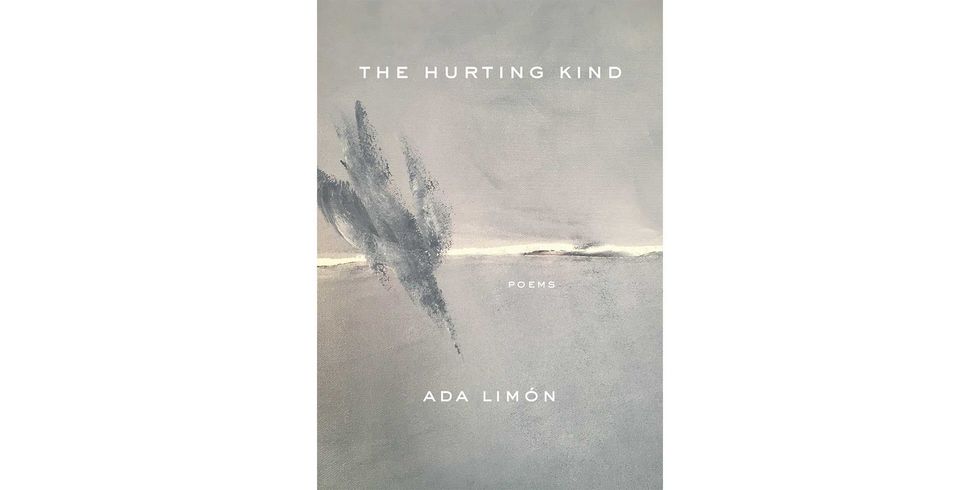

One of the most dependable providers of this feeling is Ada Limón, whose forthcoming collection, The Hurting Kind, will be published in May. Like Sharon Olds and Pablo Neruda, the poets she most resembles, and clearly learned from, Limón is a lover. She writes like a hyperporous lover of the world. She loves the Sonoma she comes from. She is a lover of men, of animals—the dogs in her life must sleep like angels—and of experience. For the heart-squeamish, there might be too much figurative saxophone in her work; that’s no matter. She has learned how to make many languages of love. Love is not simply, in Limón’s poems, an overwhelming form of desire; it is also an issue of belonging, of loyalty, of familiarity and friendship. The sheer volume of her work allows her to parse these values from longing, from nostalgia, from memory, from grief and guilt.

This article appears in the Spring 2022 issue of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

Keeping up this intensity across six books has been a thing to behold, like watching a fire juggler who has never stopped, not for nearly 20 years. It is, in fact, quite a radical posture, too, in a culture that treats time as a mineral and behavior as always optimizable, for a poet to again and again throw herself into the breach. “What I have / done,” she writes in the 2015 National Book Award finalist Bright Dead Things, “is risked everything for that hour, / that hour in the black night, where one / flashing light looks like love.”

One has to think of singers to come even close to this absolute fealty to love, to actionable passion. In this sense, Ada Limón is not the poet you give your friend with a subscription to the Economist; she is, however, the poet you give to a friend who had Dolly Parton or Tina Turner on their answering machine. Limón’s poems are not manuals for love any more than Turner’s or Parton’s songs—let alone Rich’s or Lorde’s love poems, which are among their best—are. But Limón’s are records of a heart’s revolution. Touch even an old one, like the incredible “Miles Per Hour,” which appears in her 2006 debut, Lucky Wreck, and you can feel its heat still, hear its pounding.

that throbbing in the middle of my eyes

when we knew it was over, all of it and yet

we were still in the car, still going to meet

the family and when we pulled over on

Old Sonoma Road under the tree to make

love once more before the parental hand

shake made love more difficult, more

permanent, my head swelled not knowing

whether or not to hold onto the handle

or the stick shift or to shove my foot

on the dashboard or just to remain pinned

like that

What happens to aging troubadours, though? Anyone over 30 knows that passion requires risk and, well, an increasing amount of stretching. But can this receptivity to longing be sustained—without becoming a reflex? Or a form of decadence that shades toward lubricity? How does passion live in a heart warmed by the slow-stoked fires of domesticity? In practicality—or even in regard to energy—these are not easy musings. In terms of art, these questions have plagued poets of love since the beginning of time.

If in life there are arsonists of love, addicts of love, and mathematicians of love, Limón has proved that you can temporarily be all of the above and more if you permit yourself to also question the fundamental place of a human in the world. From the beginning of her work, as she has tracked her heart’s orientation, she has slipped in and out of the skin of various animals, imagined herself from one element to another, perched herself on the branches of the trees surrounding her, and tuned her animal ear to all life about her, like some “creek-thing” who grew up with “gobo-leaf prints on my bare limbs.”

As a result of this constant tuning, Limón’s work ripples with sensory input. Her poems pull you in close to their “conch-dark night” to better ponder the moral eddies of a nation when “this country’s gone standstill and criminal.” Who better in recent years has listened to “the massive ocean inside me” or peered up at “clowned-out clouds” or clocked “flashlight-white eyes” of cats in the brush, sniffed “the burnt-meat smell / of midweek cookouts” or followed a groundhog “slippery and waddle thieving my tomatoes.”

This richness gives hint to the bestiary that lives within Limón’s work, which has a species breadth deserving of its own Attenborough special. Her poems are full of bats, dolphins, dogs, horses, koi, cranes, and snakes, both benign and not. There are possums and fireflies, peacocks and hawks, deer, mice, crows, and eagles, the aforementioned groundhog, and still more birds—of every possible variety under the sun—from cormorants to “cardinals brash and bold / as sin in a leafless tree.”

The bestiary is at once metaphorical and cosmological, qualities of force that allow us to understand love not simply as attraction, as regard, but as a compulsion in nature that desires to connect: think of it as where E.M. Forster (whose fictional motto was “Only connect”) crosses over with Louise Erdrich (“Some people meet the way the sky meets the earth,” she wrote in her book Tales of Burning Love). Creating this magnetic field, rather than just telling rock-anthem ballads from its sway, is where Limón the love poet pierces the lip of something cosmic, and eternal.

In this way, Limón’s deepening appreciation for—her receptivity to—nature is a profound glimpse into how longing transforms us; it’s also the ultimate way to sidestep the risk of staking a poetic life on love. This is not to say that passion recedes, or that the poems grow chilly. As Limón’s books progress, we watch her, in one thread, growing up and older, leaving home, falling in love, losing family and friends, then, in time, parts of her body, and learning to love in a different way. She finds her beloved and then moves to Lexington, Kentucky, for a job he’s taken. They try for a child. Simply marking this trail across her work would be confessional; leaving parts for us, as readers, feels like honesty, and a charting of how love asks different things of us romantically as we age.

Beneath the surface of these islands of autobiography, an alluvial power spreads, deepens, forms caverns and pools. Its greatest source is the energy unlocked by Limón’s third book, Sharks in the Rivers from 2010, in which she roams across the rivers of her life, from the Russian in California to the Skagit up in Washington State, contemplating “What impossible longing” brings the oak and the manzanita to water. She studies a bird outside her window, whom she names Stanley, and wonders why she is not more like him, “as if wings themselves could be willed.” Strange, wonderful, pleasurably hard to pin down, the book is an attempt to claim this spirit, to say from the beginning that we are creatures: “You are part weather, part flower-leaf waving,” she writes, angling into an oracular mode that has stayed with her ever since. “So / much of America,” she riffs, “belongs to the trees.”

“Body of Rivers,” one of Limón’s finest poems to date, emerges in this project, carving a study of will and longing into the language of the riverine.

The river comes to the body bold,

dreaming of black hues and a gestured

cluster of colored fish. This is the way

the world runs through us, its instruments of moon-

water and hangnails of hope.

With time, Limón has found a way to merge her slightly loquacious, headlong style with the mythic confidence of these fable-like poems in which the elements are given agency and personality equal to those of humans, and humans are seen caught up in our built environment, our cathedrals of shame and technology. In her strongest work, this scrambling of signals leads to moments of almost unbearable emotional clarity, especially when Limón is writing on what Jack Gilbert called the “great fires” of life: love and regret, longing and grief. In other words, questions of survival.

In Bright Dead Things, her fourth book, for the first time Limón is able to compress these styles together, in a series of poems mourning the death of her stepmother.

Her job,

her work, was to let the machine

of survival break down,

make the factory fail,

to know that this war was winless,

to know that she would singlehandedly

destroy us all.

It’s interesting to read Limón against a poet like Louise Glück in Ararat, also a book of mourning, the poems lengthening, loosening, but containing a flood and fury. Limón, by contrast, has more honky-tonk sound and spoken vernacular in her lines. “Sometimes, you have to look around at the life you’ve made and sort of nod at it, like someone moving their head up and down to a tune they like.” In the wake of death, Limón watches desire bloom with fascination, writing of her own new love and her father’s (as a widower) at the same time with this immortal phrase: “Still the bone / remembers, still it wants (so much, it wants) / the flesh back, the real thing.”

In The Carrying, her fifth volume and the winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry in 2018, shadows grow in her work where light once showed. Fear brittles her lines, drying up their usual alluvial flow. Even long, tender gardening poems, set in broad text-block shapes akin to that used by Robert Hass in “Meditation at Lagunitas,” cannot quite plunge their roots deep enough into ritual—what we now call self-care—to find hope there. A feeling is arising from within, spreading acid in the soil where Limón typically raked out poems of magic and nurturing, or wild gratitude. It’s a fear that the world might be more cruel than she had given it credit for being.

It’s the rare poet who will follow such a grim thought, wherever it takes them. Limón, poet of rock anthems and moonlit bad decisions, has to learn, in The Carrying, all over again that there is a point at which hope ends and something else—not reality, but a fact of existence—takes over. Most painfully, in The Carrying, she learns this while trying and not managing to bear a child. The directness and lack of shame with which she writes of this journey, of its aftermath, of her rejuvenation, and the hardening of her attitude among those who carelessly tell her she ought to have, should have, procreated, mark the book as a milestone in enlarging the sphere of the imaginary to meet the actual. Not having a child is not a failure; it is simply a fact.

What if we looked to the earth this way? “I am always superimposing / a face on flowers,” Limón writes in The Hurting Kind, her forthcoming volume, which arrives in a penumbra very different from her early work. With the breezeway between human and animal already established in her older poems, these benefit from Limón’s easy fluency with the connection points between the two—and with the spirit level that runs beneath it all. “My beloved and I are lying in bed,” she writes in “Forsythia,” “talking about how we carry so many people with us wherever we go…. We are both expecting to hear an owl as the night deepens. All afternoon, from the porch, we watched an Eastern towhee furiously build her nest in the untamed forsythia with its yellow spilling out into the horizon.”

All the animals of previous books are here and more. The cats that, in The Carrying, she describes taking in after her husband’s ex died; a fox; horses in foaling season, when they stand in twos all over the grass. As in other books, she relates the shock of finding dead animals on the road, or in the backyard. In one poem, she buries a fledgling dry-eyed, nursing this thought: “Seems like a good place for a close-eyed / thing.”

If in previous work Limón aged desire by expanding its definition, out of the human and into longing and the animal world, The Hurting Kind reinterprets the elegy as part of a new evolution. In nature death is commonplace, and in observation we often breathe heavily on the wrong instrument: it’s not our watching that gives breath to meaning but in the turning of seasons, where lungs so huge they cannot be seen move the wind.

Cycling from spring into summer, and fall into winter, these new poems attempt to pace a natural world harassed by human handprints. The poet even feels tempted to turn away.

I see it

is not one tree but two, and they are

kissing. They are kissing so tenderly

it feels rude to watch, one hand

on the other’s shoulder, another

in the other’s branches, like hair.

One of the greatest challenges of our time is to see the living world as having value beyond us. To acknowledge the damage done. What if, Limón appears to be asking in this remarkable book, the best we have made, the finest instrument we know, is our language of love? Are we really going to stand on ceremony and say, No, it’s anthropomorphic thinking to apply it to these magnificent creatures all around us? Perhaps love is endless when you think of it that way: There is no aging out. No endpoint. No time in which you cannot sprawl across the car seat with heat. Who really wants to turn to a cypress and make it ask—had it the language—the question this fierce poet has asked herself, over and again, the first question of this book: “Why am I not allowed / delight?”•

John Freeman is the host of the California Book Club and the editor of Freeman’s, the final theme of which is Conclusions, out this fall. He is the editor of The Penguin Book of the Modern American Short Story and Freeman’s and an executive editor at Knopf. His latest book is Wind, Trees. He lives in New York.