How to Be a Good Person Without Annoying Everyone

There’s a simple trick to provoking better behavior, without seeming like a self-righteous jerk.

You’ve heard the joke: How do you know someone’s vegan? Don’t worry; they’ll tell you. The punch line to the punch line, though, is that they very deliberately may not.

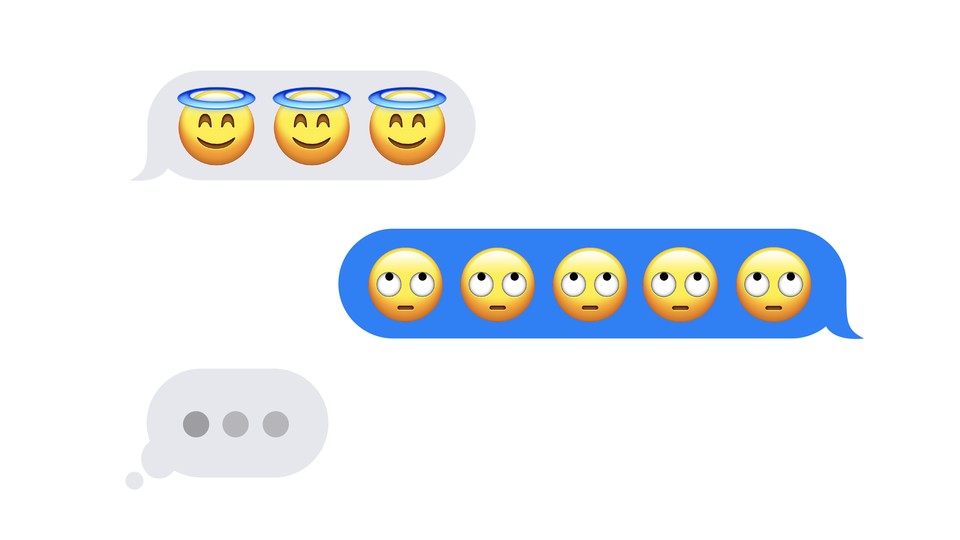

Vegans and vegetarians are aware of their reputation as sanctimonious killjoys—so aware that nearly half of the non-meat-eating participants in one recent study declined to promote vegetarian options when in the company of unsympathetic meat eaters. Their caution is well founded: The people psychologists call “moral rebels”—those who depart from the status quo out of personal conviction—can, in fact, provoke irritation and defensiveness among like-minded peers. Their behavior is especially aggravating to those who are capable of making similar choices but have not yet done so. (How do you really feel about your cousin’s superior carbon frugality? Be honest.)

Although those rebelling on behalf of the planet have good reason to pipe down, we might all be better off if they didn’t. As the social psychologists Claire Brouwer and Jan-Willem Bolderdijk argue in a new paper, “moral threat may be a necessary ingredient to achieve social change precisely because it triggers ethical dissonance.” In other words, moral rebels can annoy the rest of us into joining them. To succeed, however, they must choose their language with care.

One reason moral rebels inspire defensive reactions in so many of us, Brouwer and Bolderdijk say, is that their example highlights the gap between our own values and behavior. Maybe we’re worried about climate change, too, but we went ahead and bought that cheap air ticket to Europe; maybe we’re convinced of the importance of civic participation but we haven’t bothered to attend a city-council meeting. “Moral rebels tend to remind you of your inconsistencies, which can be very painful, because it can lead to the conclusion that you’re not a good and moral person after all,” Brouwer, a Ph.D. candidate at Pompeu Fabra University, in Barcelona, told me.

So while it’s common to perceive moral rebels as scolding or lecturing, that judgy voice we hear may be internal—our own minds pointing out our own shortcomings. And because those who care most about the issue at hand tend to be the most self-critical, they may also be the loudest scoffers. But these same strong emotions, Brouwer and Bolderdijk suggest, can act as “motivational fuel” for change. “That people react negatively doesn’t mean you’re not having an influence. It means you’ve struck a nerve,” Bolderdijk, an associate professor at the University of Groningen, in the Netherlands, told me. Rather than trying to avoid provocation, he said, moral rebels should seek to provoke more productively.

Researchers have found that people face up to and address their moral inconsistencies when they consider themselves capable of improvement. Moral rebels can bolster this confidence, Brouwer said, by presenting their own behavior as the result of an ongoing process instead of an overnight transformation. Those who devote time to a political issue, for instance, might describe the small but meaningful wins that keep them motivated. Those who have given up a pleasure or convenience for ethical reasons might admit to occasional lapses or temptations. (Instead of “Meat makes me gag,” vegetarians might try “That smells so good—steak’s the thing I miss the most.”) Emphasizing the value of incremental steps, Brouwer said, helps convince listeners that change is attainable.

Brouwer added that moral rebels should also acknowledge the external pressures and realities that shape everyone’s behavior. By recognizing that dietary preferences are influenced by childhood experiences, for instance, or that transportation choices are limited by local availability and cost, they can make clear that their intent is to encourage particular actions, not pass judgment on individuals. After all, even those who set a moral example in one aspect of life may struggle to do so in another.

Why bother with moral rebellion in the first place, though? Despite ExxonMobil’s implications to the contrary, individual consumers cannot reverse climate change—or any other environmental ill, for that matter—and their choices are no substitute for systemic reforms. Yet collective action, consumer and otherwise, does have real power, and, as Bolderdijk pointed out, collective action begins with a solo act.

“Social change is almost always initiated by individuals, whether they are consumers, activists, or politicians,” he told me. “All of them stand alone at first, and all of them face the struggles and social costs of being the first to deviate from a norm. We need these stubborn individuals, these people who are willing to stick to their guns and keep explaining their principles, in order to set change in motion.”