Diego Rivera was never one to shy away from the spotlight. But due to events beyond the famed artist’s control, one of his largest murals has remained tucked away in the Sunnyside neighborhood of San Francisco for decades. Now, following more than three years of exhaustive planning, the 74-foot-long, 22-foot-high Pan American Unity mural is on display at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, right in the heart of the city.

The massive art piece was commissioned as part of the Art in Action exhibit at the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939–1940, which featured Rivera himself at work while crowds watched. The Mexican painter was an international star and, at times, a controversial one. A communist, atheist, and member of the occult society Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis, Rivera was as outspoken as he was talented. His presence at the exposition was a huge draw.

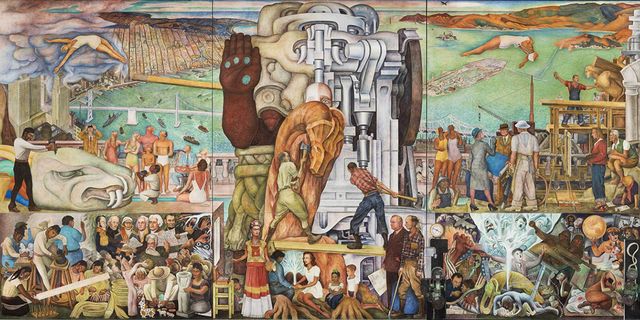

Painted directly onto wet plaster, Rivera’s Pan American Unity mural is technically a fresco—one that languished in storage for 20 years following the exposition. Originally titled The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on This Continent, the richly toned mural depicts numerous scenes of North America’s past, present, and future across 10 steel-framed panels. Following the exposition, Pan American Unity was intended to be installed at a new library at City College of San Francisco, but when plans for that building fell through, the mural found an eventual home at the school’s theater. City College, for those unfamiliar, is nestled in the southern reaches of San Francisco, closer to the sand dunes of Fort Funston than to the hustle and bustle of more-populous areas. Pan American Unity has lived there, all 1,600 square feet of it, since 1961.

That is, until last week. Rivera fans—local and tourist alike—can bask in the staggering style and size of Pan American Unity at its new, easily accessible home in the museum’s free-to-the-public Roberts Family Gallery. My late grandmother Yvonne McDevitt Peterson, famous for her “the time Diego Rivera sketched me” story, would be over the moon.

Rivera began working in San Francisco long before painting for the exhibition crowds. He and his wife, artist Frida Kahlo, arrived in November 1930, as Rivera had been hired to paint murals for the lunch club at the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts. According to McDevitt family lore, this is when Grandma had her run-in with Rivera. A striking bachelorette in her 20s, my grandmother had taken an office job in San Francisco’s financial district. One afternoon, she popped into a downtown coffee shop and an older man approached her and asked to draw her portrait. Grandma agreed. When he was done with his sketch, the stranger signed it “Diego Rivera” and handed the portrait to my grandmother.

Thrilled, Grandma headed home to Pacific Heights, where she presented the artwork to my great-grandfather, an Irish immigrant who, if the family lore timeline is correct, had recently lost his fortune in the stock market crash. Instead of being delighted, my great-grandfather announced, “I won’t have that communist in my house!” and demanded Grandma turn over the sketch. It was never seen again.

Did Rivera really sketch my young grandmother in a FiDi coffee shop circa 1930? Was this stranger artist merely an impostor looking to flirt with a pretty woman? Could I have inherited much more than my grandmother’s coffee table? Grandma told this story with enthusiasm and conviction into her ninth decade, so no matter who drew her portrait, the tale lived a longer life than that sketch ever did.

I like to think that if she were alive today, my grandmother would make her way to SFMOMA to take a nice long look at Rivera’s Pan American Unity mural, point to a woman depicted in one of the artist’s complex and colorful scenes, and declare, “That’s me!”•

This essay was adapted from the Alta newsletter, delivered every Thursday.

SIGN UP

Beth Spotswood is Alta's special projects director. In addition to her work for Alta, Spotswood has contributed to 7x7 Magazine, San Francisco Magazine, Discovery Channel, Slow News Day, KGO Radio, SFist and the San Francisco Chronicle, where she had her own weekly column in the Thursday edition of the newspaper. Spotswood's work in Alta has been recognized by the San Francisco Press Club, Los Angeles Press Club, and the FOLIO Awards.