Lodi is a small farming town in California’s fertile San Joaquin Valley, east of I-5 between Stockton and Sacramento. The town has a Spanish-style arch spanning its quaint main thoroughfare, a proud history of wine cultivation, and a large number of car dealerships, partly because farmers are sometimes paid in lump sums and tend to like to splurge on new vehicles.

Back in the 1970s, Lodi’s Cadillac dealership—Peters Pontiac-Cadillac-GMC—was thriving. The decade was a tough one for the auto industry—the oil crisis, stricter emissions and safety standards—but owner Lou Peters was weathering the storm. Personable and hardworking, he had earned promotions at the corporate offices of General Motors in Detroit before purchasing the Lodi dealership in 1970. Over the next six years, Peters boosted sales volume by 500 percent. For a stretch that decade, his dealership was the largest Cadillac distributor in California. Peters resided in a plush home in Lodi with his wife and three daughters. He was prosperous, successful, and comfortable.

Then in June 1977, a local real estate developer walked into 45-year-old Peters’s wood-paneled office behind the showroom. “I have some people that want to buy your agency,” he said.

“It’s not for sale,” Peters told him.

“But name any price,” the man said. “They’ve got all kinds of money.”

Peters figured his dealership was worth $1 million, so he threw out a wild figure, just to test the guy. “$2 million,” Peters said.

The developer came back a couple of days later. “They said that $2 million is OK.”

For Peters, who’d grown up poor in rural Maine, $2 million was a fortune. But first he insisted on knowing who was behind the deal. The developer said the buyer wished to remain anonymous. But Peters—as you might expect from a car salesman—was the persistent type, and he kept pushing until the developer finally revealed the buyer.

“Have you ever heard of Joe Bonanno Sr.?”

Peters hadn’t.

“He’s the head of the Mafia for the whole United States.”

Peters was stunned. What in the hell was the Mafia doing in a nice place like Lodi?

He told the developer, “If I’m gonna deal with these people, I’m gonna deal with them direct.”

The developer agreed to set up a meeting.

Three days later, Peters made the 90-mile drive to San Jose, where a thick summer fog often rolls in from the Pacific over the Santa Cruz Mountains. There he met with Bonanno’s two sons, Salvatore and Joe Jr., at a construction company they owned. The real estate developer was an acquaintance of Salvatore’s.

Salvatore Bonanno was hefty in his middle age, quick-witted and articulate. His little brother, Joe Jr., was less sharp but handsome and gregarious, a former rodeo rider, fond of drag races and demolition derbies. They told Peters they were looking to spend $30 million to $40 million on a string of car dealerships in California.

They offered him a salary of $100,000 a year to identify and purchase 12 to 14 dealerships. They’d supervise the operation and provide the cash. But it would have to be Peters’s name on the paperwork, not theirs.

It dawned on Peters: the Bonannos were trying to launder money through California car dealerships. And they wanted Peters as their frontman.

But he wanted no part in such a scheme. Peters despised the Mafia. “Once they get in a town,” he’d later say, “they’re just a bunch of animals that take advantage of everyone and everything that they can.”

Peters ended the meeting without giving the brothers an answer. He jumped into his Cadillac, drove straight to his friend Mark Yates, Lodi’s police chief, and recounted what had happened.

“Oh my God,” Yates said. Lodi, for the most part, was a peaceful town. Sure, you got the occasional rowdy drunks, drug users, or break-ins. There had even been a handful of murders in the past decade. But nothing like the Mafia.

“This is too big for me,” Yates said.

He alerted Special Agent Bob Anderson in the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Stockton office, an outpost of only four agents. Because of its location between San Francisco and Reno, the federal investigators there handled mostly interstate crimes like transporting stolen property. Anderson had never worked an organized crime case.

But he was well aware of Joseph Bonanno. Nicknamed the Old Man (and Joe Bananas by detractors), Bonanno had immigrated to the United States from Sicily in 1924 and become the boss of one of New York’s infamous Five Families. As a Mafia leader, he’d been suspected of dispatching hit men to kill rivals, snitches, and other enemies. His criminal career stretched from Prohibition to the late 1960s, when—according to organized crime investigators—two rival bosses learned he was scheming to assassinate them in a plot to become the nation’s supreme Mob boss. In response to the treachery, the Mafia’s ruling committee—known as the Commission—agreed to spare Bonanno’s life in exchange for his ceding control of his crime family. Stripped of his power, Bonanno chose to retire in Tucson, Arizona.

Although Bonanno had been investigated for crimes ranging from illicit gambling to loan sharking to heroin trafficking, the FBI had never managed to convict him. Bonanno even appeared in a Parade magazine article in which the aging don—said to have inspired Marlon Brando’s character in The Godfather—gloated about the FBI never having caught him. Part of the difficulty was that many of Bonanno’s most lucrative businesses were conducted by registered—and otherwise legitimate—companies. The FBI had tried to “turn” many of the people running these operations but failed.

Maybe Peters would be different, Anderson thought.

Anderson invited Peters to meet at his office, near the deepwater Port of Stockton, with its big, smoke-belching cargo ships and rusty World War II submarine moored on the steel-gray waters.

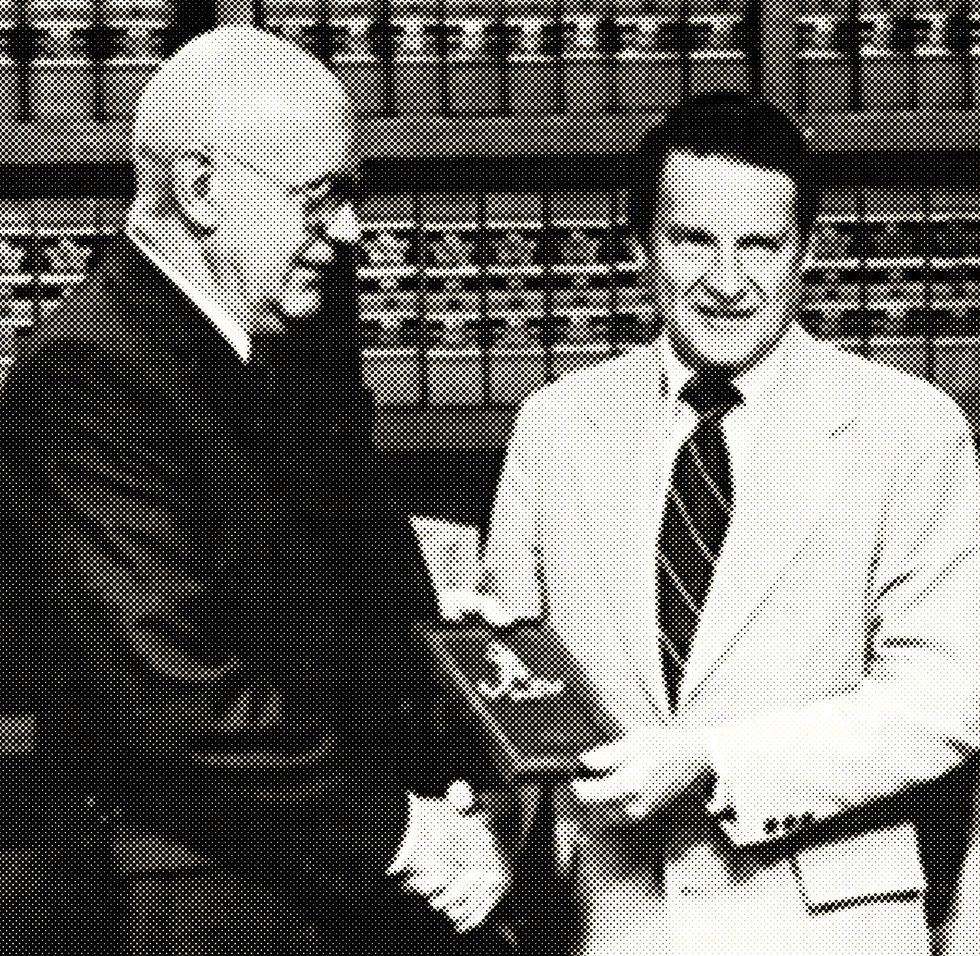

The special agent, who’d previously worked in the FBI’s Dallas office investigating the Kennedy assassination, showed Peters pictures of Salvatore Bonanno and Joe Jr. Less-savvy criminals than their father, both brothers were on probation after serving prison time for an extortion charge; Salvatore owed the IRS about half a million dollars. Peters was able to identify Salvatore from his picture but wasn’t sure about Joe Jr., whom he’d met only briefly.

Anderson asked Peters whether he’d be willing to go undercover to gather information on the Bonannos. He cautioned that the operation might take years and that it could be dangerous.

Peters said he’d need the night to think about it. He went home and asked his wife, Marilyn, but secretly he’d already made up his mind. Having served in the Marine Corps, become a successful businessman, and raised a family, Peters had checked off all his life goals. Except for one: becoming an FBI agent.

He’d been jailed for a petty theft as a teen back in Maine—siphoning gasoline from a stranger’s car after his own ran out—so he assumed he’d never pass the bureau’s background check.

Marilyn was scared for her husband but accepted his logic: “If I don’t do it, who else will?”

In the morning, Peters told Anderson, “I’m in 100 percent.”

Over the next three years, with no formal training—only his wits—the Cadillac dealer would sacrifice his marriage and risk his life to become the first private citizen to infiltrate the American Cosa Nostra.

The Old Man—a suntanned, silver-haired 72-year-old—lived in a custom-built brick house in an upper-middle-class neighborhood of Tucson. He was lonely in his retirement. His sons were in and out of prison. He felt hounded by overzealous law officers and misrepresented by reporters. His friends had abandoned him. He considered building a bocce ball court but had nobody to play with. His only company in Tucson were his ailing wife, Fay, and his loyal black-and-tan Doberman, Greasy.

Periodically, he’d visit his sons in San Jose. Salvatore, his eldest, had moved to the city a decade earlier from New York to be closer to his wife’s family, and Joe Jr. had followed.

The Old Man liked California. He fondly recalled his first cross-country road trip, in the spring of 1941—the feeling of freedom and adventure while driving out west from New York with his family in the car that embodied the best of America in its power, style, and beauty: the Cadillac. They traveled through Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah before arriving in California, a place of sea breeze and big sky. And opportunity.

Now the Old Man found himself considering a business opportunity. It was over dinner at the Gazebo in Los Gatos in the summer of 1977 with Salvatore and his son’s new friend, Lou Peters. The Old Man was impressed by the Cadillac dealer’s success and credentials and felt he’d make a good partner for Salvatore. “I’m glad you got together,” he said in his thick Sicilian accent, putting his hand on Salvatore’s and Peters’s shoulders. “You’ll both make a lot of money.”

In March of this year, I called Peters’s FBI handler, former special agent Bob Anderson. He’s in his 80s now, living in Roseville, California. We talked on the phone because his retirement home wasn’t allowing visitors owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. “You’re catching us at the end of our time,” he told me. Much has been written about the Bonannos, including a bestseller by Gay Talese called Honor Thy Father, which was based on a cover story for Esquire, and memoirs by Joseph Bonanno (A Man of Honor), Salvatore Bonanno (Bound by Honor), and Salvatore’s wife, Rosalie Bonanno (Mafia Marriage)—which make you question the sincerity of the Mafia’s “code of silence.” I also collected court records related to the Bonanno investigation from the National Archives Catalog and 1,000 pages of declassified FBI reports through a Freedom of Information Act request. The reports paint a picture of Peters as bold, committed, and eager to help the FBI. Says one early report: “He appears most cooperative in this matter and expressed extreme interest in assisting the FBI in any manner possible.”

After recruiting Peters, Anderson learned that the elder Bonanno had $40 million in Canada. The money was under the care of a Cosa Nostra member, the informant said, but once Bonanno died, it could be seized by the Canadian government. According to the informant, the Old Man sought to pass his wealth to his children by laundering it through U.S. businesses with heavy cash flows, like car dealerships.

Another informant—former Mob hit man Frank “the Bomp” Bompensiero—had told the FBI that Bonanno was far from retired, that he’d moved west to fill a “Mafia vacuum” and to set up a new crime family in California. But the Bomp was no longer available for questioning: he’d been shot to death at close range with a silenced handgun earlier that year.

Peters, now working undercover, continued to meet with the Bonanno brothers to discuss the sale of his Cadillac dealership. He posed as a businessperson who had no qualms about accepting Mafia money. He secured an oral agreement from the Bonannos to purchase his dealership for $2 million. But first, Salvatore Bonanno said, he needed the Old Man’s sign-off. “I don’t make a move without my father knowing about it,” Salvatore said.

Anderson and Peters figured that if the Old Man forked over the $2 million, then the FBI could prove the money was illicit and make a case against Bonanno. But Peters said they’d first need approval from General Motors, which owned 49 percent of his business. In January 1978, Peters and Anderson flew to Detroit to discuss the matter with General Motors’ executive vice president. After several meetings on the 14th floor of the auto giant’s Detroit headquarters, the company’s executive board voted not to authorize the sale of Peters’s dealership to the Bonannos out of concerns about bad publicity, legal liability, and the safety of workers at a Mafia-owned dealership.

Despite the setback, Peters—who could have won an Olympic medal for talking—continued to find ways to learn more about the Bonannos’ money-laundering activities.

“For a while,” the Old Man recounts in his memoir, “Peters kept calling on Salvatore just to offer to do favors for him, any kind of favors. Peters offered to lend cars, sell cars, buy cars…anything at all.”

Indeed, Peters sold three cars to Bonanno family associates and two to Salvatore’s family. He also sold three or four cars for Salvatore, including Salvatore’s personal vehicle—a maroon Cadillac with cloth seats. The car was brought onto the lot, reconditioned, safety checked, and sold by one of Peters’s salesmen for $11,000, which Peters paid to Salvatore in cash.

Peters reported everything back to Anderson, who coached him on what types of information were permissible in court. The two were an unlikely duo: Anderson was a cautious and meticulous G-man. Peters was a six-foot-three, 240-pound, pushy car salesman with wild ideas. “Peters sometimes wanted to step over the line,” says Anderson, “so we had to talk to him a little about that.”

One of Peters’s bold ideas was enticing a nephew of the Old Man’s, a San Jose commodities trader named Jack DiFilippi, to partner on a business venture customizing Pontiacs and selling them under the name Barchetta. Peters and his sales manager, a former race car driver, had created a prototype—a silver-and-black Firebird sports car with side exhaust pipes that resembled the famous 1920s and ’30s gangster car the Duesenberg. Peters got DiFilippi interested by claiming that he’d been flooded with orders for Barchettas. Peters said he’d sell the sports car’s patent and distribution rights for $1 million, and DiFilippi promised he could get funding from the Old Man and DiFilippi’s offshore network, which included investors in Germany, Holland, Kuwait, and Central America.

In October 1977, DiFilippi called Peters’s home. The car dealer’s beautiful 20-year-old daughter answered the phone, and DiFilippi suggested they all get together sometime. “Lou just blew up,” Marilyn recalled later. To protect his wife and their daughters, Peters told Anderson he needed to get a legal separation after nearly 25 years of marriage.

“It’s not expected,” Anderson said. “No one would ever ask you [to do this].”

“No, but I’m just stating what I’m going to do,” Peters said.

Marilyn felt devoted to the case too—she was equally concerned about a Mafia presence in Lodi—and agreed to the separation. “The hardest part was telling the girls,” Peters recalled later. Forced to keep his undercover mission a secret even from his daughters, Peters assured them that he and their mom were separating purely for business reasons and only temporarily.

Anderson found Peters an apartment in Stockton and arranged for it to be wired with surveillance gear. FBI technicians were lowered into the chimney headfirst to install some of the equipment. They bugged the kitchen, bedroom, phone, living room—“everything but taking a leak in the bathroom,” Anderson recalls. One tiny camera was installed behind a painting of a tiger, with the lens in the eye of the animal. Anderson also rented the apartment upstairs, from which he’d monitor the conversations between Peters and their targets.

There were plenty of close calls. At one point, DiFilippi—who worried that he was being watched by the FBI—scoured the apartment for surveillance and looked right at one of the cameras from a few feet away, but didn’t see it. Another time, on a hot day, Peters was wearing a recording device underneath his sports coat, and DiFilippi—in an aggressive tone—insisted he take off the jacket. Quick-thinking Anderson telephoned down to Peters’s apartment. “Lou,” he whispered, “tell him there’s a woman you’ve been trying to seduce for years…and if you come RIGHT NOW, she wants to have a session with you.” Peters hung up the receiver, delivered the tale, and managed to escape with his coat on.

Through Peters’s undercover work, he and Anderson began learning the names of one Mafia member or Bonanno associate after another, across the United States. They learned that Bonanno and his criminal organization controlled a big chunk of America’s cheese and pizza businesses through cheese companies and distributors. Many of Bonanno’s dealings were with corrupt businesspeople. “It was disappointing to me,” says Anderson. “How could a citizen of our country associate and deal with the Mafia just for money?”

Peters and Anderson were collecting valuable evidence, but the Cadillac dealer and the special agent had a bigger prize in mind. They wanted the Old Man.

In the spring of 1978, the government revoked Salvatore’s and Joe Jr.’s probations—for their failure to file accurate monthly reports of their income—and the Old Man traveled from Tucson to San Jose to see his boys before they were sent back to prison. Peters asked the Old Man whether he could do anything to help during this difficult time and even attended one of Salvatore’s court hearings as a show of support.

After Salvatore and Joe Jr. returned to prison that summer, the Old Man and his wife stayed in San Jose to be with the boys’ families, and Peters continued to call and visit the Bonanno patriarch.

On one occasion, Peters invited the Old Man to see his dealership, and Bonanno agreed. He viewed Peters as a friend to his sons and hoped Peters could help Salvatore find employment after his release from prison. Although he viewed Peters as somewhat brash and pushy—“totally American in his manners and outlook,” he’d later write—the Old Man was also hungry for camaraderie.

Peters picked Bonanno up in his Cadillac, and they drove to Lodi, where Peters toured him around his showrooms and lots and presented him the Barchetta prototype. Peters urged the Old Man to expedite the Barchetta purchase, insisting that Salvatore and Joe Jr. “would have employment in the manufacturing of [the] car,” according to court documents. Bonanno agreed to discuss the progress of the deal with DiFilippi.

Afterward, driving to Peters’s apartment, Peters turned to the Old Man in the passenger seat. “You know, my dad came from the old country,” he said. “There’s a lot of mannerisms and things that you do just like my dad.” Then Peters abandoned subtlety. “My dad, as you know, passed away a couple years ago,” he said. “You’re like a second dad to me.”

Peters’s dad was a Greek immigrant, not Italian, and as Peters later said, “the resemblance of [Bonanno’s] mannerisms and my father’s was like a jackass and a human being.” But as any good car salesperson knows, you build trust with your customer by connecting with them on an emotional level, and Peters noted to himself that the Old Man seemed pleased.

This professed desire for a fatherly connection fit a theme that Bonanno was exploring in A Man of Honor, the memoir he was writing at the time. “Americans also miss the extended family and are having a difficult time trying to find a substitute,” he wrote. “Americans yearn for closeness. Most of all, and I say this in a figurative sense, Americans yearn for a ‘father.’ ”

At Peters’s apartment, the Old Man joined him for a glass of expensive cognac. The hidden cameras were capturing the action as Anderson recorded the live feed upstairs. Peters expressed a fascination with the Mafia, pretending to be in awe of the Bonanno mystique. The Old Man—perhaps workshopping his memoir—opened up to Peters. He spoke about his childhood in Sicily and the origins of the word mafia. “Mafia is honor, courage, a friend,” said Bonanno.

The Old Man could be expansive. He often quoted Aristotle and Dante and name-dropped famous acquaintances like President Franklin Roosevelt, Errol Flynn, and Meyer Lansky. Ominously, he boasted about outliving a rival Mafia boss who had ignored his wishes. “He went,” he said. “I’m still here.”

On another occasion, Peters took Bonanno to Stockton’s Saturday-night stock car races. Straight out of the film American Graffiti (which was set in nearby Modesto), more than 2,000 rowdy car fanatics had gathered for the raucous event. In between races, Peters and his sales manager staged a competition in a pair of homemade, Volkswagen-powered cars resembling go-karts. Peters, less skilled behind the wheel than his manager (the ex-racer), buzzed around the track at an unremarkable 60 miles per hour as the debonair old Sicilian—with a taste for sapphire and ruby pinkie rings and expensive cigars—watched in the stands surrounded by fans slurping beer and chewing on snacks from the concession stand.

Peters also continued to meet with DiFilippi about the Barchetta venture. DiFilippi was planning to give a presentation to potential investors, but the Old Man, who by now trusted Peters, said, “Let Lou make the presentation.” By the end of the summer, the Cadillac dealer and the don had become close. Peters offered Bonanno a Cadillac for his drive back to Arizona, but the Old Man politely declined.

The feds, meanwhile, had been probing Bonanno and his sons on several fronts. In addition to the Lodi operation, the U.S. Organized Crime Strike Force in San Francisco had launched a grand jury investigation into businesses owned by the Bonanno brothers—including the construction company where they had initially met with Peters—that were suspected of being used to launder money.

Agents were also surveilling the Old Man’s Tucson residence and, twice a week, collecting his garbage, which they sifted through for possible evidence. At first, Bonanno’s dog, Greasy, barked at the agents when they tried to get near the cans. But after they started giving the Doberman hamburger beef, it warmed to the G-men, wagging its tail when it saw them.

Back home in Tucson, in September 1978, the Old Man received a call from Peters, who said he was in Los Angeles for a convention and wanted to come visit. The Old Man said he and his wife didn’t feel well, but Peters insisted that it was just a short flight away and that it would be a true honor. The Old Man relented.

Bonanno’s driver met Peters at the airport and chauffeured him to the Old Man’s home. Bonanno warmly embraced him—they greeted with a cheek kiss now—introduced him to Fay, then led him on a tour of the house, including his basement office. Cluttered with personal notes and pages from his memoir in progress, the room was, Bonanno said, his “sanctuary.” Peters scanned for a safe but didn’t see one.

Bonanno and Peters then went for a long walk. Bonanno spoke more freely outside; he’d recently discovered that his house was bugged. The issue was being handled, he said. “If there’s a problem, it’s all over,” he added, motioning with his hand to indicate slashing a throat. Bonanno explained how desperate he was to get his sons released from prison: “We’re pulling out all the stops now.” He said that his sons’ prison sentences upset him; he believed that a nefarious presence was targeting his family—and he intended to find out who.

Peters lingered after dinner—he said he hadn’t had a chance to book a hotel—so Bonanno invited him to sleep in the guesthouse. “Don’t you know you’re part of the family?” Bonanno’s chauffeur told Peters. In the morning, Peters dutifully set off to visit Joe Jr. at a prison south of Phoenix.

As his informant work stretched on, Peters became fearful that his cover might be blown. After a lunch meeting in San Jose with DiFilippi, who was the suspicious type, Peters returned to his hotel room and discovered his briefcase had been rifled through. Another time, a Bonanno associate drove him to a remote area, and Peters feared it was to bury him there. Then there was the anonymous phone call reported to the FBI. (The name of the individual who received it is redacted in the case records.) The caller said that he knew about an FBI informant inside the Bonanno organization and that the rat would be murdered.

Most frightening for Peters was traveling to Miami with DiFilippi to meet a potential Barchetta investor. Anderson was assigned to shadow him, but someone changed their flight at the last minute—likely concerned about a tail—and Peters got separated from Anderson. Alone in a hotel frequented by the Mob, a terrified Peters shoved the dresser and chairs against the door of his room because he was convinced someone would enter and push him off his eighth-floor balcony.

Alone in his Stockton apartment, he’d often lie awake thinking of his wife and daughters, missing them dearly. He got to see them only for the occasional weekend dinner out, with Anderson and fellow agents scattered at nearby tables to provide protection (and to drive him back to Stockton if he drank too much). His middle daughter, Lori, with whom he had a close relationship, tearfully pleaded with him, “Are you [and Mom] getting back together?”

Of course, he told her. But he couldn’t say when.

For protection, Peters carried a pistol. As a young Marine in Korea, where he’d fought in the bloody battle of Heartbreak Ridge, he’d discovered he was capable of taking a life. He’d joined the Marines because he’d felt humiliated being jailed for the gasoline theft as a teen and wanted to make amends by serving his country. Now, fighting against the Mafia, he felt a similar patriotic duty.

In Washington, D.C., meanwhile, Anderson’s supervisor was growing impatient. After more than two years, the quirky Cadillac probe had produced nothing that he thought could be used in court, and he decided to shut it down. Peters was devastated. And Anderson was furious. He sent reports back to D.C. detailing the numerous people they’d connected to the Mafia and accusing the bureau of abandoning Peters. “He feels like he may have been played for a fool,” said one report, and “nothing could prepare him for the shock of possibly being deserted by the FBI under his present exposed circumstances.” The reports bought them a couple more months, but in January 1979, the investigation was officially shuttered.

Peters and Anderson brainstormed how to “extract” Peters from the operation—FBI lingo for severing Peters’s ties with the Bonannos. They considered a fake heart attack, since Peters had suffered two in the mid-’70s. Instead they decided to get Peters subpoenaed to appear before the federal grand jury investigating Bonanno’s sons. It would allow Peters to tell the Bonannos that things were becoming too hot for him.

A few weeks later, Peters was served with a subpoena, and he called the Old Man from his dealership office. The telephone was connected by wires to a tape recorder hidden in the top drawer of a locked cabinet. With the recorder running, Peters first wished Bonanno and his wife a happy Valentine’s Day, then said he had something important to discuss.

Bonanno—worried the FBI might be eavesdropping—said he’d call back, left the house, and dialed Peters from a public telephone booth.

Peters, quite nervous, told Bonanno about the subpoena.

Bonanno asked what the grand jury could possibly want with Peters.

Peters, from car sales, knew how to identify someone’s need. Was it to impress a girl? Win a promotion? Fulfill a childhood fantasy? He knew Bonanno worried about his boys. The Old Man felt he hadn’t been there for Salvatore and Joe Jr. when they were kids. Now, in the twilight of his life, Bonanno felt the need to make it up to them. The need to protect them.

Thinking on his feet, Peters told Bonanno the subpoena might be connected to the Cadillac he’d sold for Salvatore—the maroon one—for which Salvatore had asked to be paid in cash.

The Old Man panicked. He knew Salvatore was in debt to the IRS, and if his son had sold the car for cash without reporting it, he’d be in deep trouble.

Peters—skilled at maneuvering a customer to make the buy—added that he’d kept records of the transaction and asked if he should dispose of them.

Bonanno was desperate to protect his eldest son. He told Peters to get rid of the records.

With those words, Peters knew what he had: obstruction of justice. He went straight to Anderson to deliver the tape.

Anderson copied tapes only if Peters felt they contained useful information. “Should I make a duplicate?” he asked.

“Well,” Peters said nonchalantly, “you might as well.”

They listened together as the tape was duplicated. Suddenly Anderson jumped out of his chair. “You’ve got him!” he shouted. “You’ve got him!”

That spring, Joe Bonanno was indicted by the federal grand jury in San Francisco for conspiring to obstruct justice. The indictment charged that he’d attempted to interfere with the grand jury probe into schemes to launder money through his sons’ companies in San Jose.

Jack DiFilippi was named as a coconspirator. He’d become involved after visiting Peters’s Stockton apartment and helping to stash the records of Salvatore’s car sale.

“Where is the dirty linen that you got over here?” asked DiFilippi when he arrived at the apartment.

“Yeah, where is it?” said Peters, fetching the records from his briefcase. “I got a pile.”

Peters and DiFilippi hid the files in the bedroom closet, with Peters helping to slide them under a box on the top shelf because shorter DiFilippi couldn’t reach. Outside, DiFilippi noticed a van parked on the curb and asked Peters about it nervously. Peters said it was a neighbor’s. But really it belonged to the FBI.

On March 17, 1979, the FBI raided Bonanno’s house in Tucson and ransacked his basement sanctuary, collecting the notes and pages of his incomplete memoir. “Never have I felt so humiliated,” Bonanno later wrote. “I can only compare it to what a woman must feel when she’s being raped.”

Peters told Anderson he was willing to testify, but Anderson worried about Peters being “hit,” a very real risk. One FBI report warned that the “possibility of retribution to silence Peters must be considered due to Bonanno, Sr.’s propensity for violence.” Following the indictment, in accordance with legal procedure, the Old Man’s attorney received a box of evidence. It contained FBI field reports referencing a concerned citizen who’d assisted the government: a car dealer named Louis E. Peters. The Old Man realized why the Cadillac dealer had been so nice: Peters was a snitch.

In the lead-up to Bonanno and DiFilippi’s trial, Anderson learned something chilling through an informant: a Vegas hit man had been sent to kill Peters.

Anderson quickly arranged for Peters to enter witness protection. He flew with him to San Diego and rented him a beachfront apartment in the wealthy enclave of La Jolla. “Figure if you’re going to hide somebody, let’s do it in style, right?” Anderson recalls.

The Old Man and DiFilippi’s trial commenced in the summer of 1980 at the U.S. district court in San Jose. Peters emerged from hiding to testify. The government supplemented his testimony with numerous recordings and handwritten notes found in the Old Man’s trash, including instructions to his sons on how to set up front businesses and references to California car agencies and to Peters. Bonanno’s lawyer argued that the Old Man had been entrapped by Peters and challenged the constitutionality of the FBI’s digging through Bonanno’s trash.

The trial continued after Peters testified, and Anderson wanted to keep him in La Jolla for safety. But Peters refused. He missed his family—except for visits and phone calls, he had been away from them for almost two years. He’d been drawn to the thrill of going undercover to bust a Mafia don, but he saw how the Old Man’s life had left him lonely and isolated in his old age, with his two sons in prison. Peters wouldn’t make the same mistake. No, he told Anderson, he was going home to his family.

Back in Lodi, Anderson persuaded Peters to wear a bulletproof vest to the dealership. But the bigger threat proved to be Peters’s physical health. The first sign of trouble had been a feeling of faintness in the courthouse hallway, which his doctor had chalked up to stress. But then Peters drove off the road, feeling like his brain had shut down. Two weeks after testifying, he suffered a seizure at home and collapsed. A brain scan revealed a large, cancerous tumor. Doctors at the same hospital where Anderson's wife worked as a nurse operated a few days later and removed the growth. But the cancer had already spread too far. Doctors told Peters he had six months left to live.

Peters’s middle daughter, Lori, told me over the phone that she thought her dad’s cancer had been caused by the physical and mental strain of his investigative work. After everything her father had sacrificed, it was unfair that he might not even live long enough to see the trial’s outcome.

But he did live to see the day: September 2, 1980. The decision was handed down by Judge William Ingram, who’d fought in World War II and, like Peters, was a Marine Corps veteran. “The Peters episode leaves no room for reasonable doubt,” Ingram said. He found Bonanno and DiFilippi guilty of conspiring to obstruct justice; it was the Old Man’s first felony conviction in a 60-year life of crime.

“We got the bastard finally,” Anderson says.

Bonanno was sentenced to five years in federal prison and DiFilippi to two. But owing to the Old Man’s claims of failing health, he served just one.

Retired attorney Craig Starr, who prosecuted the case against Bonanno, told me over the phone that Bonanno’s conviction was significant. “Some people may regard [obstruction] as fairly light,” Starr said. “But it’s a very serious crime because it’s an attack on the integrity of the justice system itself.”

Peters received the U.S. Attorney General’s Meritorious Service Award. He accepted a special plaque from the FBI director at the bureau’s headquarters in D.C., walking with a cane and wearing tinted glasses to correct his failing vision.

Lou and Marilyn Peters renewed their vows at Lodi’s First United Methodist Church in a festive ceremony. Their three daughters wore purple dresses, and FBI special agent Anderson was the best man.

Peters’s will to live led him to volunteer for experimental cancer treatments, and he survived six months beyond his doctor’s prognosis. But on July 20, 1981, Lou Peters succumbed. There were rumors around Lodi that his death had been staged by the FBI, or had been a Mafia hit. But Lori told me that she was sitting beside him in the hospital when her father took his last breath.

Peters received a military funeral with a Marine Corps honor guard and was buried in Lodi. His tombstone bears a phrase he’d chosen: “Honor Thy Country.” It was his retort to the title of Talese’s bestseller about the Bonannos, Honor Thy Father.

After Peters’s terminal diagnosis, he was asked if he regretted spending the last two years of his life as an FBI informant in pursuit of Bonanno. “I would do it again,” Peters said. His only regret was taking a night to think about it before he accepted the mission.•

Andrew Dubbins is an award-winning journalist and the author of the forthcoming book Into Enemy Waters: A World War II Story of the Demolition Divers Who Became the Navy SEALs. His story “When the Mafia Came to Lodi” for altaonline.com won a 2021 SoCal Journalism Award from the L.A. Press Club.