Santa Monica lifeguard Arthur Garrett swam through the black heaving ocean toward the fishing boat Patsy Jane. She was disabled, dead in the water, pitching and rolling on a 25-foot swell. There were two aboard on that stormy night of December 5, 1945: Chester Gannon, 30, and Dee Sharbono, 32. Garrett would have known nothing about them—just that they needed rescue.

Garrett was naked to the waist in the cold Pacific and equipped with only a pair of yellow rescue tubes. Back then in the 1940s, the inflatable life-saving devices were still experimental, sometimes deflating during rescues, but they were easier to haul on long swims than the heavier steel rescue cans that lifeguards dubbed Rescue Torpedoes.

Garrett’s training was to never take his eyes off the victim, in this case the wallowing fishing boat. But to get past the break, as each huge mountain of water rose up out of the ocean, he’d have to dive underneath. Plunging into the murky, roiling darkness, the ocean turning colder as he neared the bottom, Garrett would have felt the power of each wave as it passed overhead, briefly sucking him backward. Diving under large waves, lifeguards learn to claw their fingers into the sandy sea bottom to hold themselves steady. The first rule of ocean safety is to respect the sea, and you learn it quickly, swimming under a wave four times your height.

This article was featured in Alta Journal's free Weekend Read newsletter.

SUBSCRIBE

Behind Garrett, the waves thundered ashore onto Santa Monica Beach, kicking up a salty mist in the darkness. The swells had spilled over the heavy rocks of the Santa Monica breakwater as if they were pebbles and had beached seven small vessels on the sand. Farther south, in Redondo Beach, the waves had washed out the sand beneath a theater, forcing work crews to hurriedly prop it up with heavy beams of timber. The Hermosa Beach pier had been shut down after the surging waves broke off the end section, then washed it ashore like driftwood.

The wind screamed around Garrett as he moved through the Santa Monica Bay, with the sky dark above him and the sea dark below. At last, after a 500-yard swim, he reached the Patsy Jane, rearing and groaning under the fury of the wind and the brutal blows of the sea.

Garrett fitted the two fishermen with the rescue tubes and dragged them through the storm-tossed waters to a rescue boat. The task required a level of stamina, ocean savvy, and courage that would seem superhuman to most, but Garrett was particularly well suited for the mission. He’d just returned home from the Pacific Theater, where he’d served in an elite, pioneering unit of maritime warriors.

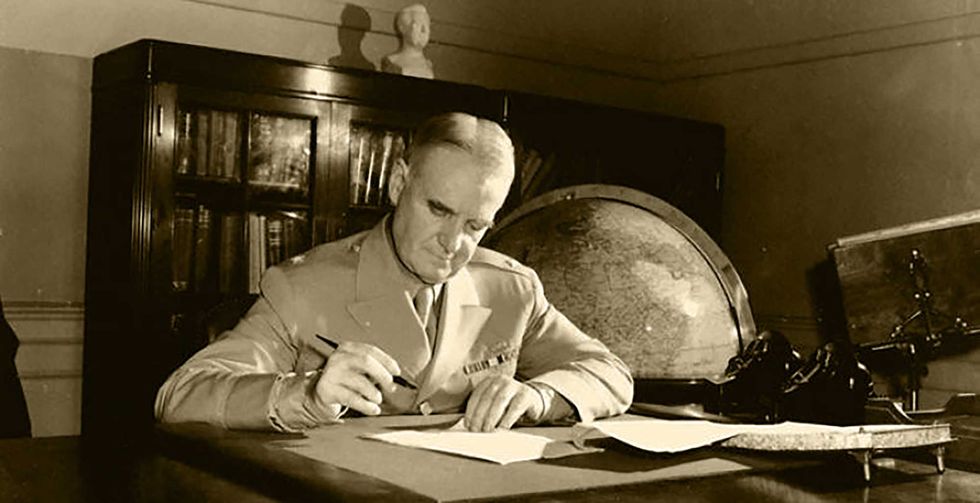

On July 11, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt signed an order appointing William “Wild Bill” Donovan to create America’s first spy agency, which would come to be called the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). A precursor to the CIA, the agency was divided into branches including Counterintelligence, Special Operations, Research and Analysis, and Morale Operations. Donovan, a World War I Medal of Honor winner turned Wall Street lawyer, also envisioned a Maritime Unit, filled with expert swimmers who could carry out reconnaissance and sabotage missions by sea.

One of Donovan’s first recruits into the Maritime Unit was a 34-year-old Hollywood dentist named Dr. Jack Taylor. With bright blue eyes and sun-streaked brown hair, the handsome Santa Monica native was renowned for his dental expertise but saw the work merely as a means to finance his passion for adventure. Eager to escape the tedium of dental work, the licensed pilot would take exotic holidays such as mining for gold in the Yukon Territory, where he once narrowly escaped being buried alive inside a gold mine. A consummate thrill seeker, Taylor was particularly fond of sailboat racing. He was a founder of the Santa Monica Yacht Club and had piloted his own boat solo across large stretches of the Pacific Ocean.

The globe-trotting dentist was a perfect fit for Donovan’s daring unit of swim saboteurs. In addition to being a world-class sailor, Taylor had served as a Santa Monica Beach lifeguard in his teens and had broken numerous swim records in high school. Into his 30s, he remained an avid skin diver and counted many of Santa Monica’s lifeguards, divers, spear fishermen, and surfers as friends.

They rode the waves of Malibu on longboards and dove for big bull lobsters at the Venice Breakwater. They used locally made rubber swim fins and dive masks, which most of the world had still never heard of. They devised their own wet suits before the term was even invented, wearing woolen underwear in the winter months. They went fishing for sharks (which were targeted for their liver oil) and chased the barracuda that swarmed L.A.’s waters in those days. The royalty of the watermen were the Santa Monica Bay lifeguards, who got to do it all on a government salary.

Some called this bunch beach rats, but they referred to themselves as watermen. They were exactly the sort of men Wild Bill was looking for.

After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Los Angeles and its beaches quickly moved onto a wartime footing. Air raid sirens blared, and searchlights scanned the night sky. Blackouts and anti-aircraft guns became common along the coast. In February 1942, a Japanese submarine surfaced off Santa Barbara and shelled an oil installation. Los Angeles too had regular reports of Japanese subs offshore. Local beaches were fenced off and converted into military encampments to prepare for a potential Japanese invasion. Malibu became a fortress, its wooden pier used as a lookout post. The Coast Guard moved its headquarters into the pool house of the Adamson estate, military convoys rumbled through town, and barbed wire surrounded Surfrider beach. Most surfers found new spots, but it is said that one diehard continued to paddle out to the point break by moonlight.

With America at war, the OSS Maritime Unit ramped up its recruiting efforts. Merely competent swimmers wouldn’t do; the unit’s recruiters wanted the finest in the country, including Olympic-caliber swimmers and university champions. The OSS combed the navy and Coast Guard for top swimmers, and—almost certainly due to Dr. Jack Taylor’s influence—began scouring the beaches of Los Angeles for ocean lifeguards and watermen.

Imagine The Dirty Dozen, except instead of convicts, the recruits were muscular, suntanned beach rats, with sand in their hair, salt water in their ears, and surfboards under their arms. They were the unlikeliest secret weapon in the war against the Axis, a group of hardy young swimmers more comfortable in the ocean than on land.

Arthur Garrett joined the Coast Guard, long referred to as the guardians of the sea, before being recruited into the OSS. As an ocean lifeguard, Garrett was a magnificent swimmer, in top shape, and knowledgeable about the Pacific, its powerful waves, swift currents, stinging jellyfish, and deadly great white sharks. He was also a leader. Lifeguards carried themselves with dignity and pride as trained professionals and city representatives. Garrett’s fellow lifeguard John Tabor, who in 1942 became the county’s first African American lifeguard, recalls being taught to be a “role model” for his “fellow citizens.” Recognizing Garrett’s leadership potential, the OSS made him an officer, assigning him to prepare his men for an audacious form of maritime warfare that had never been tried.

Twenty-one-year-old Robert Scoles was part of Hermosa Beach’s crack lifeguard squad, which was credited with hundreds of rescues and recognized as one of California’s most efficient crews. He surfed at Hermosa Beach in his free time and swam laps in the pool. “He was beautiful to watch in the water,” a friend would later say. He was poised to compete in the 1942 Olympics. “But the war put an end to that,” Scoles would recall. His father had volunteered in France in the early days of World War I, and Scoles felt a similar patriotic duty. Like Garrett, he joined the Coast Guard, where he was approached by a recruiter for the OSS.

“You think you could swim to Catalina?” the recruiter asked.

Scoles’s long-distance swim record was 22 miles, and Catalina Island is about 20 from the tip of Palos Verdes. “Yes,” the young lifeguard answered.

Fellow Hermosa Beach lifeguard Jim Eubank grew up in Inglewood and started working at a young age after his father abandoned the family. To help put food on the table during the Depression, he rode his bike to the ocean to teach himself to swim and became a lifeguard. He won a few rough-water swim meets and was soon competing against the world’s best, like Buster Crabbe, who won gold in the 1932 Olympics and starred in the film Tarzan. Eubank joined the Coast Guard in 1942, while his sweetheart Vera—a music student—volunteered to provide music therapy for wounded servicemen returning from the war. Eubank spent a few boring months on the Coast Guard base as a swim instructor, when he heard a loudspeaker announcement requesting volunteers for a new special outfit called the OSS Maritime Unit. He was warned the work would be hazardous and that members had a 10 percent chance of survival. Vera couldn’t fathom why he’d volunteer, but she agreed to marry him when he got home.

Twenty-four-year-old lifeguard Frank Donahue had grown up in Santa Monica and spent his teen years surfing next to the Santa Monica Pier, skin-diving for lobster and abalone and fishing off the coast on one of the many commercial trawlers that used to crowd the Santa Monica Bay. Donahue had an interest in the film business, and his job as a Santa Monica lifeguard provided some exposure to Hollywood. Stars like Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, and Cary Grant frequented the beaches stretching from Santa Monica Canyon to Venice, often attending costume parties at the enormous Santa Monica Beach mansion of silent film star Marion Davies. Off-duty lifeguards sometimes made a little extra cash as Hollywood stuntmen, diving off cliffs or the masts of sailboats, or fighting sea monsters in the movie Reap the Wild Wind. The Malibu lifeguard squad hosted big moonlight bonfires at Burnt Pants Beach, named after a lifeguard who walked over hot coals trying to impress the revelers but fell on his backside. One bonfire regular was an aspiring actress named Marilyn Monroe, whose boyfriend was a lifeguard. Despite the allure of the silver screen, Donahue opted for the safer route of law school. He was in his first year when World War II broke out, and the OSS came calling.

Joe Stepner was a natural fit for the OSS, one of the city’s few lifeguards who’d been shot at. Years earlier, Los Angeles had bought the water rights to the Owens Valley, diverting water from local farms and pumping it to Angelenos. The city dispatched lifeguards to patrol the area’s reservoir, Crowley Lake, where angry locals were shooting at the lifeguard boats. The lifeguard chief sent Stepner, who was six foot four, and another lifeguard, who was a former heavyweight wrestling champion, to the lake. Both had worked Venice Beach, where a big part of the job was controlling the large beach crowds. (Lifeguards prided themselves on handling unruly beachgoers themselves, never calling in law enforcement.) Through a mix of diplomacy and brawling, the two put an end to the Owens Valley shootings.

Although not a Los Angeles native, Hank Weldon was a pool lifeguard during high school in Oklahoma. He had just enlisted in a navy officer’s training program when “Wild Bill” Donovan arrived at the base looking for swimmers. Weldon decided to take the OSS test, which involved diving to the bottom of a pool, fetching a manhole cover, and placing it in a canoe on the surface without tipping it over. Weldon, who’d also played college football at Villanova, passed the test and soon found himself a member of the OSS.

In total, about a dozen Los Angeles–area lifeguards were recruited into the 226-member OSS Maritime Unit, contributing their ocean knowledge and skills to the elite group of swim commandos. Once known as watermen, they would soon acquire a new wartime nickname: frogmen.

The mission of the OSS frogmen was to insert into enemy territory by sea for the purposes of espionage and reconnaissance, to transport and supply resistance fighters, to sabotage enemy shipping and coastal defenses using underwater demolition, and to develop special maritime equipment and tactics that could be used by other U.S. military units.

The men trained at several top-secret facilities. One, called Area D, was in a bug-infested swamp a few miles south of Quantico, Virginia, on the Maryland side of the Potomac River. There, trainees learned to handle small boats, including kayaks and canoes. They studied navigation, currents, tides, nautical charts, and the art of explosives. Taylor served as the school’s chief instructor. The expert yachtsman taught recruits how to crew and sail an antique sailboat moored on the Potomac, and he organized night drills, requiring trainees to sneak out of the water past armed sentries. Training was rigorous and dangerous. Two trainees drowned when their boat capsized in the Potomac.

Another OSS training facility was located on Treasure Island in the Bahamas, where the recruits practiced blowing up replicas of enemy obstacles above the colorful coral reef and attached limpet mines to a sunken shipwreck. Whenever sharks approached the swimmers, the men cleverly emptied a sack containing dark blue powder to simulate the ink spray of a squid. The trainees also encountered an aggressive four-foot barracuda, which so often followed the swimmers, they gave him a name: Horace.

OSS recruits also had to complete the grueling Marine Raider Training Course at Camp Pendleton in San Diego County, which emphasized beach infiltration and small boat operations in the high surf.

Underwater training was held at a secret OSS base on the leeward side of Catalina Island, dubbed Area WA. The men slept on the grounds of a former all-boys boarding school located at Toyon Bay. Two and a half miles by water from the port of Avalon, the hidden cove was chosen for its seclusion, hemmed in by steep cliffs with no road in or out of the area. Even Catalina residents and other service members stationed on the island knew nothing of the base’s existence.

In the clear blue waters off Catalina, the OSS frogmen practiced underwater demolition and experimented with state-of-the-art equipment such as one-man submersibles, collapsible kayaks, a two-man surfboard equipped with a quiet electric motor that could be launched from submarines, watches with luminous dials, M-3 submachine guns in watertight covers, waterproof flashlights, compasses, depth gauges, and ordnance. Catalina was like a weapons laboratory for the frogmen, lifeguard Robert Scoles recalls: “Most of our OSS new weapons were in the experimental stage, and we were able to learn as we used them.”

The OSS men integrated the gear pioneered by the Santa Monica Bay lifeguards and watermen, including skin-diving masks with a circular glass window and black rubber swim fins designed by one of Jack Taylor’s fellow yachtsmen in L.A., an Olympic swimmer named Owen Churchill. On a visit to the island of Tahiti, Churchill had watched local boys swimming with rubber fins reinforced with metal bands. He tracked down a French inventor who’d designed his own pair and negotiated a license to make them in the U.S., originally using tire rubber. (To this day, Churchill’s fins remain a favorite among body surfers and boarders.) If a lost fin was to wash ashore on an enemy beach, the Germans or Japanese could find the name of the odd webfoot contraption stamped on the rubber—“Churchills”—along with Churchill’s address in Los Angeles: 3215 West Fifth Street.

On Catalina, the OSS frogmen went on long runs into the mountains to build their endurance and participated in a five-day survival course. Supplied with only a knife and fishing wire, they hunted Catalina’s wild boar, skinned its wild goats, and fished with their bare hands, all while dodging the buffalo that roamed the island. The men also trained in martial arts, cryptography, map reading, and radio communications. A number of the trainees were Japanese Americans and Korean POWs, who’d volunteered to serve as linguists and fighters behind enemy lines in order to drive the Japanese out of East Asia.

To practice infiltrating enemy beaches undetected, the frogmen conducted stealthy mock raids on Avalon, Two Harbors, and other locations on Catalina Island. (Eighty years later, scuba divers still find bullet casings around Avalon’s old casino.) Approaching by sea, the frogmen used the breaststroke and sidestroke, which minimize splash, and they camouflaged themselves under the piles of brown-green seaweed that thrive in Catalina’s nutrient-rich salt water. Lifeguard Hank Weldon would recall an exercise designed to test the men’s stealth. “They gave us a bunch of dummy TNT at high tide, dropped us off about a half mile offshore, and told us to plant it all along the coast while our commanding officers kept watch. One of the commanding officers said he thought he saw something, but they didn’t see us. When daylight came, the tide went out and all you could see was the dummy TNT all along the shore.”

Meanwhile, Taylor was investigating a newfangled device that promised to reshape clandestine operations. On the night of November 18, 1942, at the stately art deco Shoreham Hotel in Washington, D.C., a small group of military servicemen gathered around the hotel’s large indoor pool as Taylor slipped on a face mask, inserted a tube into his mouth, then buckled on the Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit (LARU). A primitive version of scuba, the device had been invented by Christian Lambertsen, who stood poolside among the spectators at Taylor’s demonstration. The 25-year-old University of Pennsylvania medical student had built the contraption in his garage using a bicycle pump and an old World War I gas mask. He had tested the device in a chamber filled with anesthetic gas and brought a canary and a dog inside. First the canary fell off its perch, then the dog fell over. When he bent over to check on the dog, he too passed out and collapsed. Lambertsen determined that the anesthetic gas that filled the chamber had seeped into the LARU’s breathing bag, and he’d been fine-tuning the device ever since. Taylor submerged into the pool and began swimming laps, without once lifting his head above water.

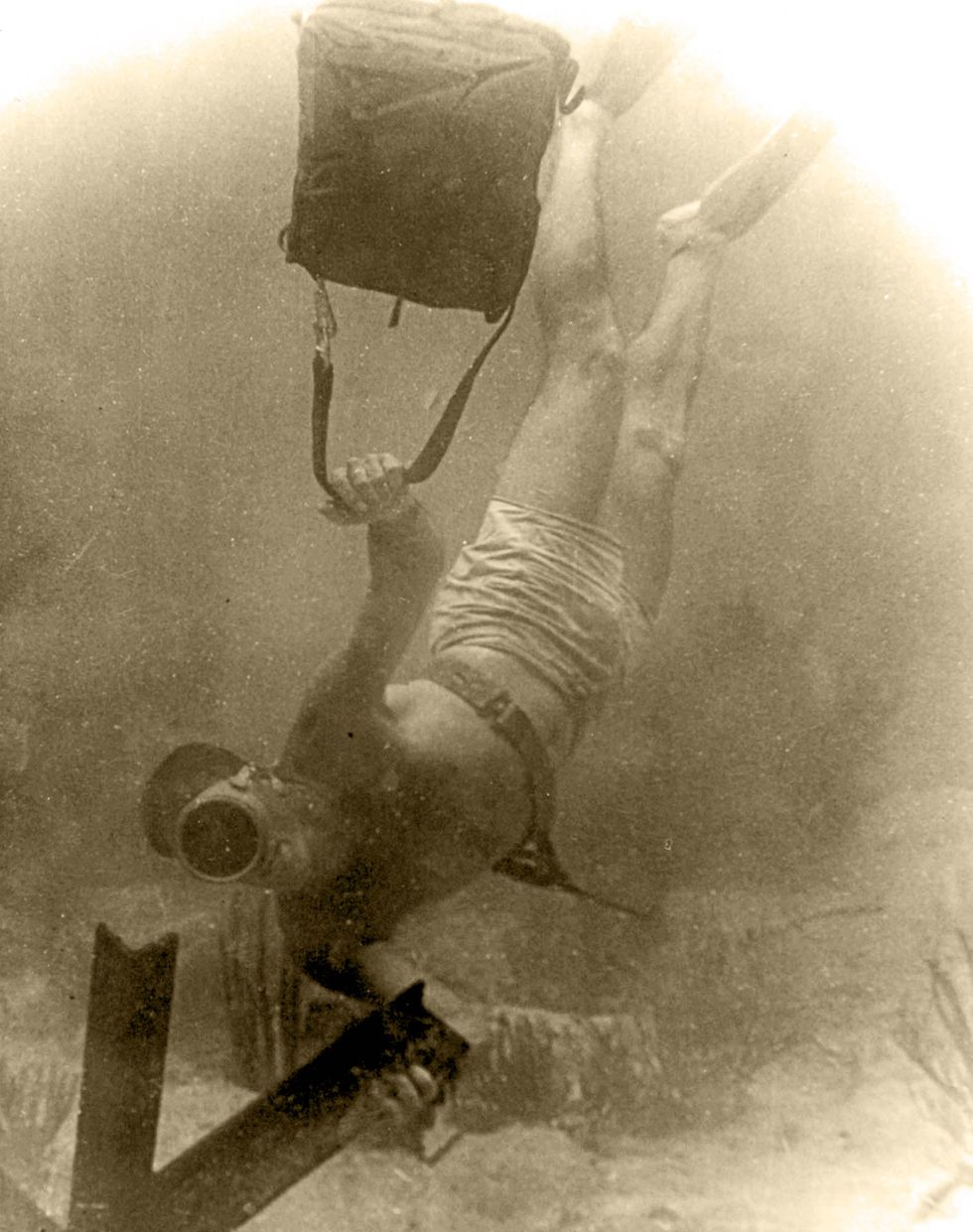

A swimming pool was one thing, but Taylor knew that the underwater equipment would need to hold up against the ocean’s rough waves and corrosive salt water. While visiting home on personal leave, he rode a boat out to sea with lifeguard George Peterson and anchored off the shore of Santa Monica. Taylor peered over the side as Peterson donned another scuba-like contraption called Browne’s Lung, then swam around the boat underwater for 20 minutes. (He could have gone longer, but the water was too cold.) Soon, OSS Maritime Unit trainees were testing the LARU and other underwater breathing devices off Catalina and in the Bahamas. They were making history—among the first to use scuba equipment in the ocean.

After their training, most of the OSS frogmen were dispatched to the Pacific, where they were integrated into the navy’s Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT). The UDT had been created after America’s disastrous assault on Tarawa in November 1943, when U.S. landing craft became stuck on the island’s shallow coral reef, forcing the Marines to wade a half mile to shore under withering Japanese fire. Determined to prevent further loss of life during island assaults, the navy resolved to deploy swimmers ahead of Allied forces to scout enemy beaches and blow up coastal defenses and natural barriers as needed.

When the OSS men reached the UDT training base on Maui, most of their navy counterparts were still swimming barefoot or in athletic shoes. The OSS men helped introduce swim fins, demonstrating how the fins increased speed and maneuverability in the water, especially over coral reefs. Although the OSS men had trained in the LARU breathing device on Catalina, the navy decided that the equipment would slow down the swimmers and loaded the primitive scuba gear into storage in Honolulu. Thus, the OSS men’s new uniform became streamlined: swim trunks, fins, and dive masks.

The OSS swimmers saw action in the Central Pacific, Burma, Indonesia, and the South China Sea. Swimming into heavily fortified Japanese beaches, they often encountered fierce enemy gunfire. Fortunately, their bobbing heads made for difficult targets. They also discovered that bullets slowed down a few feet below the ocean surface, allowing them to dive underneath the sinking ordnance. (Some swimmers caught the bullets and kept them as souvenirs. Others would later drill a hole in the sniper bullets, lace string through them, and wear them as necklaces.)

Lifeguards Garrett, Scoles, and Weldon were all deployed to the Palau islands, where America had its sights on the enemy stronghold of Peleliu, gateway to the Philippines.

Weldon’s platoon was assigned to mark Japanese anti-boat mines for the navy’s soon-to-arrive landing craft. He’d never forget the eerie experience of moving through the water above the enormous mines, which were anchored to the sea bottom and floated underwater like balloons. “A partner and I ended up treading water for a couple of hours over a live mine,” he’d later recount. “We finally got relief, and another minesweeper found the mine and blew it up.”

During an afternoon mission off Peleliu, Garrett stood on the bridge of the World War I–era destroyer Rathburne as his team of swimmers scouted the island’s beaches in broad daylight. Garrett’s role as an ensign was to monitor the swim mission and direct the American covering fire. High-caliber shells from a line of navy warships slammed into Peleliu’s shoreline to keep the Japanese pinned down while the frogmen were in the water.

A message crackled over the radio from a fellow officer in a landing craft close to shore, who reported seeing Japanese troops dragging something out of a cave. Garrett told the gunnery officer, who scanned the area with his binoculars but didn’t see any enemy soldiers. Then the officer in the landing craft exclaimed, “It’s a howitzer—a big one!”

Spouts of water erupted as if from fire hydrants all around the Rathburne. The captain gunned the destroyer’s engines and steered her out of the area at flank speed. Garrett asked about his officer aboard the landing craft. The captain—focused on the lives of his own crew—dryly replied, “Let him catch up.” Fortunately, spotters aboard a nearby destroyer pinpointed the howitzer, and the navy gunners blew it off the cliff.

Scoles was supposed to join a historic operation off Peleliu—the first-ever deployment of U.S. combat swimmers from a submarine. But his commander yanked him at the last minute because he wanted only navy men, and Scoles had come from the Coast Guard. On the night of August 11, 1944, the OSS commandos painted their faces black, climbed onto the deck of the U.S. submarine Burrfish, and paddled ashore in a rubber raft. Dodging Japanese shore patrols, they measured and scouted the enemy beach. When they were finished, a team member tapped his Ka-Bar knife on a coral head as a signal to the submarine’s sonar operator, then the group swam across the water back to the sub. Off the island of Yap in Micronesia, the same five OSS men again deployed from the Burrfish, but this time only two returned. The others were captured by the Japanese, interrogated, tortured, and never seen again.

Garrett, Scoles, and Weldon next shipped to the Philippines, where they were assigned to reconnoiter the beaches for army troops led by General Douglas MacArthur. Weldon helped destroy Japanese artillery markers and detonated boat lanes for invasion ships using a paddle board to haul the explosives. Scoles was dragging explosives through the water to blow up beach obstructions on the island of Leyte when a Japanese mortar splashed down beside him. The underwater pulse launched him upward and pushed another nearby swimmer 10 feet underwater before he surfaced, spitting blood. “When you get hit by an explosion like that,” Scoles’s partner later said, “water goes in every orifice: the ears, nose, rectum, and tears things up a little bit.” Miraculously, both men survived the powerful blast.

Santa Monica Bay lifeguard Arthur Garrett joined the scouting mission at Leyte and was awarded the Silver Star for gallantry. His commendation read: “In the face of enemy rifle, machine gun and mortar fire Ensign Garrett bravely prepared the way for the operations of combat troops contributing greatly to the success of this mission.”

On October 20, 1944, Weldon and a handful of UDT men were walking on the beach at Leyte, carrying their sacks, when they passed a man wading to shore in his khaki uniform, surrounded by photographers. The young frogmen had no idea who the person was or the reason he was being photographed, and they walked on.

A major stormed over to the frogmen. “Why didn’t you salute?” he barked.

“What for?” Weldon replied.

The man being photographed was General Douglas MacArthur, who’d fled the Philippines two years earlier and was now part of a carefully choreographed publicity stunt to accompany his famous message to the world: “I have returned.”

It wasn’t until a couple of days later that Weldon learned that the man in wet khakis was perhaps the most famous army commander of all time.

The frogmen were developing a reputation as roguish and irreverent, the problem children of the navy. During operations on Guam, one team had planted a sign on the beach to remind the Marines who had reached the island first. “Marines Welcome!” it said. “Courtesy UDT.”

Santa Monica Bay lifeguard Frank Donahue was serving as a training officer when he overheard a navy admiral insulting the frogmen and their abilities. Donahue just smiled. Then, later that night, he and some fellow frogmen swam out and placed blasting caps around the admiral’s boat. When the admiral set sail the next morning, it was to a chorus of thunderous booms. When questioned about the incident, Donahue said he’d just wanted to expose the vulnerability of the admiral’s vessel.

Although the swimmers were rebellious at times, their wartime contributions soon became regarded as essential. Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, who commanded amphibious forces in the Pacific, would later write: “Their efforts always reduced losses to troops and boats’ crews and greatly facilitated the landing of men and cargo. Their value to the Amphibious forces was immense.”

So valuable were the swimmers, they were often borrowed by other Allied nations. In February 1945, Hermosa lifeguard Jim Eubank found himself in Burma conducting recon for British landing forces. His team hitched rides on PT boats before switching to kayaks, then swam the last leg through Japanese waters. On one beach, Eubank spotted 20-foot-long saltwater crocodiles in the shallows and felt something brush against him in the water. He was utterly terrified, until realizing it was just a school of fish. At night, the OSS men rode patrol boats upriver deep behind enemy lines, silently drifting past Japanese camps, observing soldiers gathered around their fires.

On one risky mission, Eubank and his partner, John Booth, had to transport Burmese agents ashore. They gave the Burmese men opium in exchange for intel on Japanese positions. “We weren’t dope dealers,” Eubank later clarified. “This was war.”

The intel proved unnecessary. As they paddled in a raft toward the drop-off point, Japanese soldiers leapt from the trees and opened fire. Fortunately, the OSS men made it back to the ship, where they heard a radio report that Japanese forces had repelled an American invasion. “But actually it was just me and Booth,” Eubank later said.

Taylor so resented being stuck in the U.S. as an instructor that he threatened to transfer to the navy unless the OSS gave him an overseas assignment. The request was granted, and the former Hollywood dentist was deployed to Cairo in the summer of 1943, where he worked with archaeologist spies to assemble a watercraft flotilla for missions in the Aegean Sea. Next, he teamed with actor Sterling Hayden, who was a fellow OSS commando, to establish a Maritime Unit branch in southern Italy to supply Josip Tito’s anti-fascist guerrillas. While in Italy, Taylor also led a series of daring covert operations, including rescuing a plane of American medics and nurses that had crashed in the Albanian mountains.

In October 1944, Taylor was part of a four-man OSS team that parachuted into Austria to spy on the Nazis. Captured by the Gestapo in November 1944, Taylor was sent to the Mauthausen concentration camp. There, the former adventurer experienced horrors that shook him to the core. Suffering starvation and dysentery, he was forced to build a crematorium that would incinerate fellow inmates. Taylor was scheduled for execution on four occasions, but other prisoners took his place, wanting the American to survive the war and report on the Nazis’ atrocities. Taylor was on the verge of death in May 1945 when at last a U.S. armored division liberated the camp.

Meanwhile in the Pacific, after Okinawa’s capture in June 1945, the OSS frogmen began training for the invasion of Japan, where they expected a gargantuan battle in the coldest seas they’d ever experienced. But the U.S. deployment of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Japan’s subsequent surrender, meant that the swimmers could finally return home.

President Harry Truman dissolved the OSS and its Maritime Unit at the end of the war, but their legacy lives on. The early scuba experiments, swim reconnaissance, and underwater demolition tactics were codified into manuals. Eventually, the frogmen’s specialized techniques were passed down to their most famous successor: the Navy SEALs.

As for the unit’s Santa Monica Bay lifeguards, most returned to civilian life after the war.

Jack Taylor retired from the military in 1945 but was briefly reactivated a year later to serve as a primary witness in the trial of the Waffen-SS guards who ran the concentration camp where he’d been imprisoned. Taylor’s testimony was crucial to their conviction, a tribute to the inmates who’d sacrificed their lives to save him. He suffered post-traumatic stress disorder from his wartime experiences and died in 1959, crashing a private plane near his home in Southern California.

Frank Donahue, the maverick who’d nearly blown up an admiral, transitioned seamlessly into the film industry, first trapping sharks for Hollywood productions, then screenwriting and acting. He was a technical adviser and actor in the 1951 film The Frogmen, which introduced Americans to the daring exploits of the World War II combat swimmers.

Jim Eubank married Vera and became a successful real estate developer. Hank Weldon joined the Los Angeles Police Department, where he worked during the Watts Rebellion. Reportedly the last surviving member of the OSS Maritime Unit, Weldon passed away in 2018 at age 95.

Arthur Garrett and Robert Scoles returned to ocean lifeguarding. Scoles later became a schoolteacher and scuba instructor. (Many frogmen got involved in diving after the war, helping shape the sport’s development.) Pulling from some old navy diving manuals and his memories of OSS training, Scoles launched L.A. County’s first-of-its-kind scuba diving certification program. He also cofounded a program called Junior Lifeguards. Its original mission was to help the latchkey kids who hung around Scoles’s guard station and loitered under the pier, but it would eventually evolve into an organized summer camp.

I participated in the camp as a kid, running in the soft sand to the Santa Monica Pier, swimming to a buoy 200 yards out in the Pacific, learning how to plunge under waves, paddle a surfboard, and navigate rip currents. I never got to meet Scoles or any of the lifeguard frogmen, but I admire them. Theirs is a legacy of helping strangers: first as young lifeguards rescuing distressed swimmers, then as frogmen, swimming ashore to protect thousands of infantrymen they’d never meet, and, in Scoles’s case, as teachers, leading kids like me into the Pacific, where we can still swim as a free people.•

Andrew Dubbins is an award-winning journalist and the author of the forthcoming book Into Enemy Waters: A World War II Story of the Demolition Divers Who Became the Navy SEALs. His story “When the Mafia Came to Lodi” for altaonline.com won a 2021 SoCal Journalism Award from the L.A. Press Club.