Moritz Hochschild was constantly on the move. In the early 1930s, he could be found in the grand hotels of London, New York or Paris, or on the back of a mule, following rough mountain trails in search of mineral seams in the Bolivian Andes. It was on one of those trips to a remote mountain village, according to family legend, that the mining magnate came across a local man sketching. The artist was afraid to show Hochschild his drawing, which was an unflattering caricature of him. But the magnate found the parody so amusing that he decided to fund a scholarship for the artist to study draughtsmanship in Paris.

Hochschild could afford to laugh at his own expense. His shrewd risk-taking had made him one of the richest men in South America in the early 20th century, and earned him notoriety as one of Bolivia’s three “tin barons”. The trio – Hochschild, Simón Patiño and Oxford-educated Carlos Aramayo – had made fortunes trading Bolivian tin which, during the first half of the 20th century, was much in demand for aeroplane parts and food cans, and accounted for more than half of the country’s export earnings.

The barons were seen as a cartel: “a circle of oligarchs who negotiated between themselves and had more power than the state,” the Bolivian historian Robert Brockmann told me. Tin was Bolivia’s principal mineral export in the 1930s, and the tin barons controlled 72% of the nation’s tin exports, while paying just 3% of their profits to the government. The three mining barons are chiefly remembered for their ostentatious wealth, their influence over Bolivian politics and their exploitation of mineworkers. “[Hochschild] was a cruel businessman; the toughest of the three,” Edgar Ramírez, former union organiser and archivist, told me. “The president of Bolivia wanted to have him shot.”

Hochschild, the youngest “baron” by decades, was the only one who was not a Bolivian citizen. A middle-class German Jew born in 1881 in Biblis, a small town south of Frankfurt, Hochschild sought his fortune in Australia and Chile before the first world war, returning to South America as soon as the war ended to build his metals and mining empire. During the 1930s and 40s, Bolivia was swept by waves of social upheaval. Amid mass demonstrations for state control of resources, Hochschild was twice thrown in jail and threatened with execution. He escaped with his life, but fled into exile. As the country hurtled towards the National Revolution of 1952, one of its chroniclers, Augusto Céspedes, described Hochschild as a “grand pirate of mining finances”.

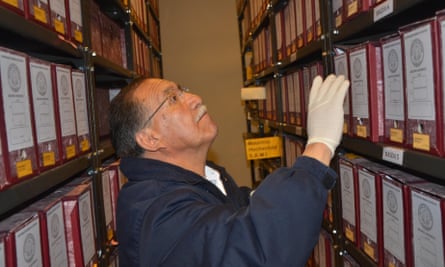

But evidence has since come to light that has forced Bolivia to reappraise its view of Moritz, known as “Mauricio” Hochschild. In 1999, several tonnes of rotting papers were found in warehouses owned by the state mining company, Comibol, which had taken over all of Bolivia’s mines when the industry was nationalised following the 1952 revolution. Documents from Hochschild’s companies were discovered piled in cardboard boxes, stuffed into barrels or dumped outside, exposed to the elements. Bolivia’s congressional library recognised the historical value of the archive, and a team was hired to organise the documents under the direction of Edgar Ramírez and the historian Carola Campos, who is now the archive’s director.

In 2004, after five years of sorting through thousands of pages of correspondence with consulates, businesses and international Jewish organisations, the team revealed their astonishing discovery. The papers demonstrated that Moritz Hochschild had helped to rescue as many as 22,000 Jews from Nazi Germany and occupied Europe by bringing them to Bolivia between 1938 and 1940, at a time when much of the continent had shut its doors to fleeing Jews. The documents, which included work permits and visas for European Jews, tracked Hochschild’s efforts not only to ensure Jews escaped Europe but also to resettle them in Bolivia, investing his own fortune and using his influence with the country’s elite to secure protection and employment for as many refugees as possible.

“This aspect of the man was unknown until we discovered these papers,” Edgar Ramírez told me in October 2020. Ramírez, a union man of 74 who still wore his flat cap and workman’s overalls, grew up in Potosí, a mining town where Hochschild employed hundreds of miners on near-starvation wages. “[He] was known in Bolivia as the worst kind of businessman. The worst!” Ramírez growled. “But who was the real Hochschild?”

After the first publication of their findings in 2004, Edgar Ramírez’s team of investigators continued to make more discoveries, and in 2005, documents surfaced in warehouses in El Alto, the satellite city of Bolivia’s administrative capital La Paz. In 2009, further south, in the mining towns of Oruro and Potosí, work permits for Jewish refugees were found scattered among the files of Hochschild’s multiple companies. In 2016, Unesco recognised the archive’s historic value and added it to the Memory of the World Register; as a result, Hochschild’s humanitarian work became more widely known. The legacy of Mauricio Hochschild, until then, had been his immense wealth; his villainous reputation, according to Brockmann, had served the architects of the 1952 revolution as a “necessary part of the nation-building myth”.

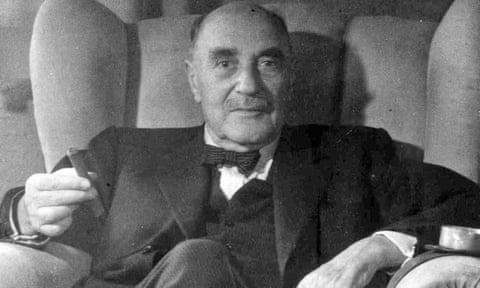

Hochschild was a towering figure. Bald-headed and moustachioed, with bushy eyebrows that framed expressive brown eyes, he resembled an “Old Testament patriarch” according to his employee and later biographer, Gerhard Goldberg. When he first started his mineral explorations, Bolivia was underpopulated and much of the country was not industrialised. Don Mauricio, as he was known, belonged to a generation of early 20th-century Europeans who believed nations could be transformed through capitalism. He mingled with Bolivia’s patrician classes and its military top brass, and sought favour with the clergy by generously donating to Catholic charities. “He possessed enormous charm and a great ability to attract people. Of this he was well aware,” wrote Goldberg. “When there were problems, his favourite reaction was ‘Let me talk to him’, and most of the time he proved capable of persuading people, often against all expectations.”

In 1929, Hochschild founded the South American Mining Company. Demand boomed from Europe and the US for metal ores, and by 1937, he controlled around a third of Bolivia’s tin production, and around 90% of lead, zinc and silver exports. He used European connections to push markets in London, Germany and the Netherlands and made frequent trips to the old continent.

As Hochschild’s business went from strength to strength in South America, the systematic persecution of German Jews was intensifying. Between 1933 and 1935, he was approached by international Jewish organisations for help, according to Brockmann, and told them that Bolivia did not have the economic capacity to receive a large number of refugees. The political turmoil in Bolivia at that time was intense, and he may have suspected – as indeed it turned out – that his own position was not secure.

But when the young war hero Lt Col Germán Busch took power in a military coup in July 1937, the two men formed a bond. “They met many times. In fact, Hochschild considered him a friend,” said Brockmann. “[Hochschild] was a man very close to power. He was sent to the US to negotiate the price of tin, invested with diplomatic status.”

By then, much of South America was aligned with Europe’s fascist leaders. Busch, aged just 34 when he became president, was half German, and his father, a German doctor, supported Hitler. Still, Hochschild managed to persuade Busch that Bolivia’s economy could gain from opening its doors to Jewish fugitives – although Busch insisted his country did not need city folk, but farmers. In March 1938, Busch signed a resolution ordering consular officials to allow Jews to enter Bolivia, particularly if they could be “useful to national activities”. Three months later, he issued a decree permitting “all men of sound body and spirit” to enter Bolivia, offering farmland and inviting immigrants to populate its “barren lands”. “In Bolivia, we should not partake in hatred and persecution,” the decree read.

“When the news reached the cities of Europe occupied by the Nazis, enormous queues immediately formed outside the Bolivian embassies and consular offices,” said Brockmann. A network of corrupt consular officials, led by the Bolivian foreign minister, took advantage of the wave of Jewish families desperate to leave Europe to charge thousands of dollars for visas and passports. (When the scandal became public in 1940, the foreign minister was forced to resign.) “Between 1938 and the first months of 1940, a breathtaking number of Jews arrived in Bolivia - somewhere between 7,000 and 22,000,” Brockmann added. A letter written by Hochschild to Edwin Goldwasser of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in March 1939 said Busch had agreed to “gradually receive 10 to 20,000 German Jews, with the priority of colonization, on the condition that enough money is made available [by the committee]”.

Hochschild leaned on Busch to ensure that the visas would be respected once refugees arrived in South America. Ramírez said that the tycoon, who was unable to travel to Europe in person, “bribed [officials] to buy blank passports”, and through his links with anti-fascist resistance groups, oversaw the creation of false agricultural work permits and identities for fugitives.

Correspondence with Hochschild’s staff in 1939 showed detailed plans for a Hilfsverein, or a welfare association for Jewish migrants, and the disposal of $30,000 of company funds for the arrival of an initial 1,000 people. Adding a $137,500 donation from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Hochschild created the Society for the Protection of Israelite Immigrants, known as Sopro in its Spanish acronym. The funds paid for a 20-bed hospital, a children’s home and a kindergarten in La Paz, and even a retreat in Cochabamba for Jews suffering from altitude in the city.

Thousands of European Jews appeared in the steep, narrow streets of La Paz and Cochabamba, where the refugees started businesses selling hot dogs, tailoring or dry-cleaning. When local people found themselves having to compete for jobs, or being priced out of rented accommodation by the new arrivals, an antisemitic backlash began. Refugees were abused on the streets, and the attacks were fuelled by antisemitic editorials in the press. Under pressure from Busch to ease tensions in the cities, Hochschild bought three agricultural estates in the high jungle region of Yungas, and founded the Bolivian Settlers Society, which managed farming projects for Jewish immigrants relocated to the countryside. The archive contains dozens of work permits registering German and Austrian Jews as agricultural labourers. But many of the new arrivals were merchants, doctors, lawyers, teachers or musicians who had no idea how to farm.

Hochschild’s immigrant farming venture was ultimately a failure but it served a short-term purpose – the deliverance of thousands of Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. Most longed to return to life in the city, and after the war left Bolivia for Israel, the US or cities in Brazil and Argentina. A smaller number of Jews were already working for Hochschild’s mining companies on meagre wages, as León E Bieber, 79, a Jewish Bolivian historian and author of a 2015 book about Hochschild, told me when we met in Santa Cruz de la Sierra. “They worked mostly administrative posts,” Bieber said, “and for Hochschild, this was important because he trusted in these people’s honesty. He paid miserable salaries compared to what he could have paid. This shows he was first and foremost a businessman who wanted to get the best out of his people.”

One of the children that Moritz Hochschild saved from the Nazis was Ellen Baum de Hess, now 94. “He was a true hero,” she told me over the phone from Buenos Aires, where she has lived for the past 80 years. In 1938, when she was just 10, Baum de Hess and her mother fled Berlin, having recently witnessed Kristallnacht, the infamous pogrom against Jews, which heralded what the future held for them in Germany. She recalls walking home from school and seeing “a synagogue burning and the broken windows of many Jewish businesses” in Berlin the following day. “That was when my mother realised that we had to get out of Nazi Germany,” she told me.

At the time there was a two-year waiting list for US visas, which also required an American financial sponsor, preferably a relative. Baum de Hess’s parents were separated, and all she and her mother were able to get was a tourist visa for Uruguay. In late December 1938, they boarded a steamship, the General San Martín, in Boulogne, in northern France. But when they arrived in Uruguay’s capital, Montevideo, more than a month later, customs officials refused to let them disembark, claiming their tourist visas were fake. Baum de Hess remembers the adults pleading, desperate to be allowed ashore, even though they suspected that the country’s government sympathised with the Nazis, or had been ordered by Nazi Germany to turn back Jews fleeing Europe. “Many of the 28 people [on board] wanted to throw themselves into the ocean because we were desperate. We didn’t want to go to a concentration camp,” she said. From Montevideo, they sailed to Buenos Aires, arriving in late February 1939, where they were held in port for three weeks before being sent back across the Atlantic.

The ship docked in Lisbon in April 1939, and while awaiting news of their fate, the passengers received reason to hope. There were rumours aboard about a mysterious well-wisher who had managed to get them visas to Bolivia. “People said there was a benefactor,” Baum recalls, “who, through his friendship with the Bolivian president, had managed to get visas for us. We were told that the only one who could have achieved that was Moritz Hochschild.”

After another three weeks in Lisbon, the passengers got word that they had been granted safe passage. They were ferried to the Italian port of Genoa and, from there, aboard another ship, the Orazio, set sail once again for South America. The refugees docked at Arica in northern Chile, the main port of entry for landlocked Bolivia, in the middle of June 1939. From there, they reached Cochabamba by train, said Baum de Hess. The rail route into Bolivia became known as the Express Judío, or Jewish Express, due to the huge influx of refugees. (Months later, in January 1940, the Orazio – carrying more than 600 mostly Jewish refugees – caught fire and sank in the Atlantic Ocean. Passing ships were able to rescue most of the passengers, but more than 100 died.)

Baum de Hess and her mother stayed in a village near Cochabamba for more than a year before making their way to Argentina, where her aunt awaited them. They did not have a visa, but crossed Bolivia’s southern border into Argentina where they boarded a train bound for Buenos Aires in December 1940. Her family could not afford to pay for her schooling beyond the age of 13, but she trained as a secretary and, owing to her command of German, Spanish and English, worked as a translator. “With very little schooling, I became self-educated,” she declared with a triumphant laugh. “I, my mother and the other 26 people owe [Hochschild] our lives, although no one knew at the time.”

A year after the president had opened Bolivia’s doors to Jews fleeing Nazi persecution, as Europe was on the brink of war, Busch and Hochschild’s relationship soured. In June 1939, Bolivia’s mining companies were given four months to hand over their foreign currency reserves to the national mining bank, which would return the funds in local currency. Hochschild, the most stubborn of the tin barons, refused to comply. Busch had an “attack of rage”, according to historian Herbert Klein, and sentenced the tycoon to go before a firing squad, before intercessions from his ministers, the US and Argentina spared Hochschild this fate.

Two months later, Busch, who had a history of depression, shot himself. Earlier that night, he had reportedly complained about the number of Jews in the cities when he had expected farmers in the fields, Brockmann said. Busch’s supporters, made suspicious by the violent circumstances of his death, accused Hochschild and the other tin barons of plotting his murder. Half a year after Busch’s death, the country’s immigration commissioner suspended the visas allowing Jews into Bolivia but, despite heated – often antisemitic – debate over their status, the proposal was not ratified in the legislature. As late as March 1943, the government issued visas to around 100 Jewish orphans in France, according to historian Florencia Durán, though by that stage, they were unable to get out of Europe.

During the war, Hochschild’s metals business became key to consolidating Bolivia’s strategic support for the Allies. He was already a key broker for Bolivian tin with the US, so was well placed when vast quantities of the metal were needed to make ammunition boxes, aeroplane instrument panels and syringes to administer morphine. In 1940, Hochschild brokered a deal between Bolivia and the US Metal Reserve Company to supply tin at 48.5 cents per pound, which boosted production but soon fell below market price. In 1942, the price rose to 60 cents, and Bolivia’s profits fell.

Another cache of documents indicates that Hochschild himself was a committed supporter of the Allied war effort. Comibol archivists showed me a blacklist of hundreds of Bolivian-based businesses with German, Japanese and Italian names. Dated from November 1939 to August 1946, the file, labelled “Trading with the Enemy”, compiled by the US embassy and the British legation in La Paz, contained a regularly updated list of firms with possible fascist sympathies or ties. Letters show Hochschild was an enthusiastic enforcer of the veto, writing cordial but forceful letters to trading partners to ensure they upheld the ban or lose his business.

In 1943, a pro-fascist military dictator, Col Gualberto Villarroel, took power in a coup, and pushed for Bolivia to switch from supporting the Allies to the Axis powers. One of the reasons Villaroel toppled his predecessor was the unfavourable tin price that the mining magnate had negotiated with the US. Hochschild became one of Villaroel’s “bêtes noires”, said Brockmann, “because he was rich, capitalist, Jewish and foreign”. In May 1944, Villarroel had Hochschild arrested, accused of treason and threatening the stability of the government, and he was jailed for 45 days, along with one of his managers, Adolf Blum. But “even behind bars”, Time Magazine reported, “Don Mauricio was still a power-center of Bolivian politics”. After pressure from the US, Chile and Argentina, he was released. In July 1944, an ultra-nationalist, pro-fascist military faction, known as Razón de Patria, kidnapped him, and Blum, and held them for 17 days. “The rebels were inspired by mixed motives of nationalism and social reform. [Hochschild] has been unpopular on both counts,” reported Newsweek.

“They kidnapped him with the intention of killing him, to send a message to the world: ‘This is what we do with the Jewish capitalist foreigners’,” said Brockmann. For Hochschild, it was the second time he had faced death after falling foul of a military president. After the kidnappers released him, in August 1944, he fled Bolivia on a Chilean government plane, never to return. A few days later, he told the New York Times he could not discuss the details of his release, only that no ransom had been paid. He made a statement to the effect that he had never plotted against the Bolivian government and “he hoped to help Bolivia adjust its postwar social and economic problems”. He also wanted to reassure the US that the kidnapping incident would not interfere with the “steady flow of Bolivian tin from his mines to American smelters”.

Hochschild’s company retained control of his Bolivian mines, and his international business continued to thrive. He moved to Chile, where years later he opened Mantos Blancos, a hugely successful copper mine in Antofagasta.

“When Bolivia turned against him … it must have been extremely painful,” said his grandson Fabrizio Hochschild Drummond, 59 – a former UN official whose employment recently ended after allegations of bullying – speaking to me on the phone from New York. “He had tried to give his heart and soul in turning this country around and it kicked him out, short of killing him.”

When I visited the neat, air-conditioned Comibol archive in El Alto, under a sign reading “Out of the trash, into the memory of the world”, three Bolivian archivists wearing blue rubber gloves and face masks were sifting through hundreds of yellowing pages of typed correspondence in German, Spanish, Hebrew and English. Among them, Ramírez, pointed out a handwritten letter addressed to Hochschild in neat calligraphy from a Jewish kindergarten in La Paz, asking for funds to build a second floor “in view of the number of children who are here and others who want to come”. He was already known to the children as the benefactor: the first floor of the school had been built by his charitable organisation. The letter, which is believed to date from 1944, includes a black-and-white photo of the students and staff, and is signed by “the children”.

After years of poring over evidence of Hochschild’s good works, Edgar Ramírez had revised his opinion of Hochschild’s legacy. He told me he now considered Hochschild a heroic figure. It was his view that the tycoon concealed his “true face” – that Hochschild was, in fact, an unsung leader in the international anti-fascist resistance. Months after my visit to El Alto, Ramírez, the driving force in the Comibol archive, died from a Covid-related illness. For more than two decades, he had led the team of archivists that conserved and restored hundreds of thousands of work and personal documents relating to Hochschild, which now fill 50 metres of specially constructed shelves.

Researchers are still puzzling over the apparent disparity between the public businessman and the private humanitarian. Ricardo Udler, a spokesman for Bolivia’s small Jewish community, believes Hochschild deliberately kept his activities quiet in order to operate more effectively. “Many people whose families arrived in Bolivia didn’t know that their benefactor was Hochschild. When the Comibol archive was opened, only then did many people in the community begin to investigate and realise what this figure, Hochschild, had done. He had been working silently, bringing many, many people. By keeping a low profile, he probably managed to get more people out.”

Before the second world war, records show there were no more than 100 Jews in Bolivia, yet by the 1940s there were some 15,000, according to Udler, a medical doctor and president of El Círculo Israelita de Bolivia, the association of the once-thriving Jewish community. The country’s current Jewish population stands at little more than 300 and is shrinking, he explained, and there is now just one rabbi in the whole country. “It is important that our children know about one of the great saviours of our history,” said Udler, 64, whose French-Polish mother survived four concentration camps before escaping across the Atlantic to Bolivia.

Just down the corridor from the Comibol archive is an imposing mural by local artists William Luna Tarqui and Jesús Callizaya, which commemorates the 1952 Nationalist Revolution. The fresco, which lionises socialist ideals, revolutionary leaders and ordinary workers, follows a Latin American tradition exemplified by the Bolivian Indigenista painter Miguel Alandía Pantoja, whose art was, by turns, glorified and vilified by successive dictatorships. The revolution resulted in the nationalisation of the tin barons’ mines – including Hochschild’s – who was compensated with 30% of the company’s prior assets.

During the revolution, Hochschild was portrayed in plainly antisemitic terms, cast as the capitalist villain who used “Judaic trickery to stretch his hand over the biggest mines,” in the words of Augusto Céspedes, a writer who championed the upheaval. While Hochschild had “unmatched personal influence with Bolivian authorities in the highest ranks of government and the armed forces”, writes Leo Spitzer, in Hotel Bolivia, a book about his childhood in Bolivia as the son of Austrian Jews, “his foreign birth – and, no doubt, the fact he was also a Jew (albeit a non-practising one) – also generated intense jealousy and dislike among some Bolivian nationals.”

Among the hundreds of Jewish families that Hochschild gave new life and hope, many did not realise until recently that they were part of a bigger group of beneficiaries. One of them is Fred Reich, 73, a retired businessman and an important figure in Peru’s 2,500-strong Jewish community in Lima. His father, Kurt Reich, was an Auschwitz survivor from Austria who got his first job, aged 26, as a messenger boy for Hochschild’s company in La Paz, in March 1947. “Only after Mauricio’s death, people have realised the amount of fantastic work he did to save Jews from the horror of Europe,” said Fred Reich at his home overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Lima’s bohemian Barranco neighbourhood. “At that time, to the best of my knowledge, it was only known that he was very sympathetic to hiring Jewish people in Bolivia.”

While working for Hochschild, Kurt Reich had discovered that one of the accountants had been stealing from the company, and reported the theft. When he heard about Reich’s action, Hochschild, who was in Paris at the time, invited him for lunch. “Going to Paris would be like going to the moon today,” Fred recounted proudly. “You have to imagine: La Paz to Rio, Rio to Casablanca, Casablanca to Lisbon, Lisbon to Paris – in small planes!” Hochschild was impressed that his father had survived the camp, said Fred. “At one point he [had] weighed 32kg, so it was quite a miracle for him to be alive.”

Hochschild promised to pay for Kurt Reich’s son’s education anywhere in the world, and Kurt went on to have a long and successful career at the company. Hochschild’s pledge was fulfilled after his death when Fred went to study at Alfred University in New York state. Fred Reich still has the letter Hochschild wrote to his father in German, telling him of his plans to visit the family in Arequipa, Peru. But Fred never got the chance to thank the man he calls the “Bolivian Schindler”. Hochschild died alone aged 84 in June 1965 in Le Meurice, a five-star hotel in Paris. His remains were interred in the Père Lachaise cemetery.

Even Hochschild’s family did not seem to have made much of his humanitarian work. Growing up in wealthy circles between London and Santiago de Chile, Fabrizio Hochschild Drummond remembers his grandfather’s achievements on the mining front were vaunted, but what he had done on behalf of the Jews was “really barely mentioned”. “I had heard stories of how he brought Jews from Germany,” said Hochschild Drummond, “but it was always presented to me, when I was a child, that it was more [for] self-interested business reasons rather than [something] altruistic and praiseworthy. So when the story came fully to light about five years ago, I was taken aback, not by the fact but by the scale.

“I remember in Chile coming across many strangers who, once they had my surname, would tell me how my grandfather had helped them at this or that time in their life.” He believes his grandfather’s deliverance of thousands of Jews from the Nazis was a “great act which has never fully been recognised”.

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, listen to our podcasts here and sign up to the long read weekly email here.

This article was amended on 12 August 2022 to revise reference to the allegations against Fabrizio Hochschild Drummond.