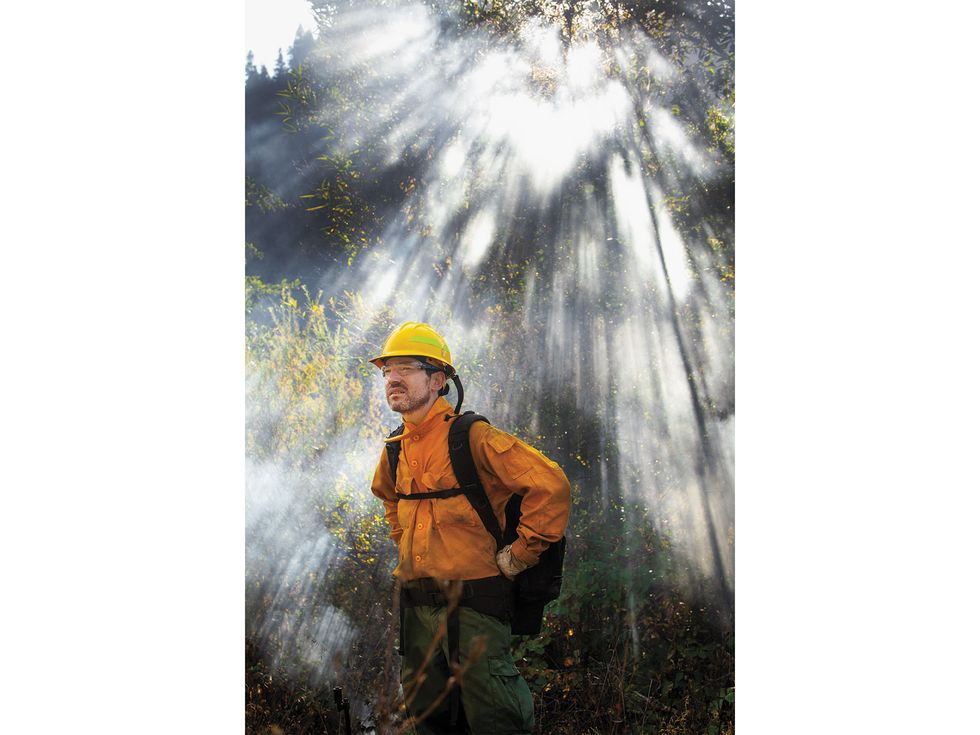

Anna Colegrove-Powell is setting the woods on fire. Her drip torch streams diesel onto dry leaves and twigs, and its flaring tip sets them ablaze. Soon, a line of orange flame sweeps through the underbrush along the thickly forested Klamath River, igniting small bushes and singeing the trunks of oaks and firs.

The sight would horrify many Californians. Over the past three years, wildfires have devastated the state, killing or injuring hundreds of people, incinerating thousands of homes, forcing evacuations, and spewing smoke into cities.

But Colegrove-Powell is not alone. The canary-yellow hard hat she wears over her waist-length hair, her yellow shirt, and her olive drab cargo pants all match those of a half dozen other fire setters, each armed with an identical drip torch. They walk in tandem, spreading fire with each step. Today’s burn has the sanction of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire), the U.S. Forest Service, and a multitude of other government agencies. It also has approval from the Karuk Tribe, which once controlled this land.

The agencies have caught on to the notion that small, frequent “prescribed” fires can prevent big, catastrophic ones. And they are studying secrets of the technique as practiced by indigenous people such as the Karuk, as well as the Yurok and the Hupa, from whom Colegrove-Powell traces her ancestry. Tribes throughout California have used fire, pruning, transplanting, tilling, and harrowing for millennia not only to prevent big fires but also to nurture thousands of species of plants and animals. “It’s amazing to see our land management practices being validated and acknowledged by Western science,” Colegrove-Powell says.

The Klamath River Prescribed Fire Training Exchange (TREX) in Humboldt and Siskiyou Counties, which brought her here on this day last October, is just one example among dozens around the state of newly assertive tribes influencing the management of their ancestral territory. In Plumas County, the Maidu people gained title to 2,325 acres of their land after Pacific Gas and Electric Company surrendered it in a 2003 bankruptcy settlement. In San Mateo County, the California Department of Parks and Recreation has been working with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band to restore 225 acres to their condition when Spanish explorers first arrived in the Bay Area. In October, the city of Eureka transferred 200 acres of Indian Island, just off its coast, to the Wiyot Tribe, which was massacred there by white settlers more than a century ago.

And even in the urban heart of Oakland, the Chochenyo Ohlone are regaining control of two acres of ancestral land, which the nonprofit group Planting Justice purchased on their behalf in 2016. The Ohlone have already planted mugwort, amaranth, white sage, manzanita, and oaks there.

These plots are only a fraction of the vast acreage indigenous people once managed. But the return of these lands, and with it opportunities for traditional horticulture, shows a new perception that policies of domination, extraction, and exploitation are reaching their limits. “I think there is a cultural shift in the world right now,” says Ohlone Corrina Gould, cofounder of the Sogorea Te Land Trust, which is managing part of the Oakland lot. “We need something different, and I think people understand that.”

THE BOUNTY OF 1769

When Europeans first arrived in California, they described a land more like a park than a wilderness. Juan Crespí, a missionary accompanying the first Spanish expedition to the Bay Area, found “uncountable” flocks of geese. Even into the 19th century, journalist and poet Joaquin Miller mentioned a river so filled with salmon that “it was impossible to force a horse across the current.” Wildflowers blanketed the hills, and pigeons darkened the sun, wrote other early white settlers. It seemed to them that the Native people wandered like children in paradise, nurtured by the land without changing it. That misconception has largely persisted to the present day.

But as best they’ve been able to, indigenous people around the state have kept alive the memories of the sophisticated stewardship their ancestors practiced, which shaped the vistas that the early European explorers sighted from their crow’s nests and saddles.

In recent decades, Western science has confirmed those oral traditions. Archaeologists have measured the frequency of fires as recorded in tree rings and have correlated those findings with carbon-dated artifacts. Botanists have analyzed the genes and growth patterns of thousands of native species, noting how some flourish when pruned or periodically cut to the ground. Historians parsing the letters of early white settlers have found descriptions of the way the land changed when indigenous people were forced to leave.

This new view of California history may have profound implications for the way we manage land today. Environmentalists, for example, talk of restoring streams and forests to their natural conditions. But what does “natural” mean?

“We have to change the idea of wilderness,” says archaeologist Mark Hylkema of the Department of Parks and Recreation. He points out that humans arrived at the end of the last ice age. As the climate changed, so did the ecosystem, and human beings played a role in that transformation. “If you want to re-create habitat,” he asks, “what time period do you want to re-create?”

Hylkema would choose the year 1769. That’s when 63 men under the Spanish explorer Gaspar de Portolá, including Crespí, made their way north from present-day San Diego in the first overland exploration of California by Europeans. Hylkema has devoted much of his career to understanding the history of one 225-acre parcel of land, the former site of the village Quiroste, 40 miles south of San Francisco. He believes this is where the Portolá expedition arrived on the brink of starvation. If the people of Quiroste had not resupplied the explorers, Hylkema says, Portolá would not have gone on to discover the San Francisco Bay.

By the end of the century, the Spanish had repaid their benefactors by enslaving most of them in missions along the California coast. Quiroste vanished, and it wasn’t until the early 1980s that Hylkema confirmed its location. Twelve years ago, the state designated the site the Quiroste Valley Cultural Preserve with the goal of creating “a native California Indian managed landscape.”

With hundreds of thousands of dollars in state and local funding administered by the Amah Mutsun Land Trust, Hylkema and people of Amah Mutsun heritage are restoring the groomed meadows and oak groves that Portolá found when he arrived. Begun in 2018, the project is a rare instance of indigenous people being paid to restore their ancestral land. Unable to set fires because of the risk to nearby buildings, they use chain saws to cut down invasive trees and shrubs and a masticator to chew up weeds such as poison hemlock and razor grass. “We run through thickets and beat them down,” Hylkema says.

Decisions about what plants to nurture at Quiroste are guided by archaeological and genealogical studies on what grew there in the past and how often the Amah Mutsun burned the site in previous millennia. It’s a new concept in historical restoration; with prehistoric cultures in California so woven into the natural world, bringing back once-flourishing plants and animals may achieve more than displaying artifacts or erecting structures, Hylkema says.

Such native plants as coffeeberry, yerba buena, elderberry, buckeye, and angelica grass are growing once again. “Quiroste is our ancestral land,” says Amah Mutsun Land Trust’s Marcella Luna of the restoration. “To reconnect with that is humbling.”

The idea of restoring Amah Mutsun practices has spread from Quiroste to a neighboring 6,000-acre parcel, Cotoni–Coast Dairies. Its owner, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, has entered into a memorandum of understanding to begin a similar transformation. “Turning land over to the Amah Mutsun would require an act of Congress, so what we do is try to work as closely with the tribe as possible,” says Ben Blom, a field manager for the BLM.

It may seem counterintuitive that burning, weeding, and pruning can increase the number of native species thriving on a piece of land. But these techniques, practiced at different times in different places, result in a mosaic of habitats, says Scott Stephens, a professor of fire science at UC Berkeley. “It would create a lot more niches for ecological diversity.”

WHAT IS NATURAL?

Ecologists debate to what degree the first people of California lived in harmony with nature. Some blame these early inhabitants for the disappearance of large mammals such as mastodons and ground sloths. And evidence from shell mounds suggests that indigenous people hunted at least one species of duck into extinction 2,400 years ago.

While many ecologists agree that the rate of destruction was a fraction of what has occurred since Europeans arrived, some say it’s dangerous to assume that all indigenous practices are benign. “Native Americans have this mythos about them that they were ecologically minded,” says Rick Halsey, a former biology teacher who directs the California Chaparral Institute. “But they were people like everyone else, and they changed the environment to increase their survival potential.”

He argues that California chaparral—a community of woody shrubs like manzanita—is destroyed by frequent burning. In Halsey’s view, chaparral existed millions of years before human beings came and hasn’t benefited from any human intervention, including prescribed burning by indigenous people. To burn it threatens not only the shrubs but also the many species they harbor, such as roadrunners, wrens, towhees, condors, mountain lions, and bobcats.

Hylkema disagrees. Whatever flora and fauna were present when the first people arrived can no longer exist in that form, he says, not only owing to human interventions but also because the climate has changed over the past 10,000 years. So, he argues, the chaparral that was growing in California when Europeans came was already partly a creation of indigenous people’s. Left alone, chaparral produces terpenes, chemical compounds that limit its growth, he says. “Native Americans burned at four-year intervals. The fact that there is chaparral now is a result of Native American practice.”

Such debates have always raged among ecologists. But what may be most remarkable about the way the conversations play out these days is that the scientists are—at least occasionally—listening to the oral traditions of indigenous Californians.

Colegrove-Powell has focused her career on this possibility, working to synthesize what she heard from her family elders and what she studied in school. When she was growing up, her family burned a stand of hazel shrubs on the Yurok Reservation, where they lived, every other year, just as they had for countless generations. After hazel is burned, it regenerates by sending up straight, strong shoots, ideal for basketry. Basket weavers still come from miles around to harvest the shoots from this family stand.

By the time Colegrove-Powell was old enough to help set fire to the hazel, in the 2000s, things had changed. Sometimes a Cal Fire spotting plane circled overhead. At least once, firefighters sprayed water on the shrubs and threatened to fine the family for arson. State and federal government agencies were pursuing a hard-line fire-suppression policy, which allowed undergrowth and dead timber to accumulate in forests—fuel for future blazes.

But in the Environmental Science and Management Program at Humboldt State University, Colegrove-Powell’s peers and teachers supported her effort to reconcile traditional and scientific knowledge. Now she works for the Karuk tribal government as a cultural resource technician.

In the days leading up to the TREX prescribed burning, Colegrove-Powell documented pre-contact artifacts in the areas slated for fire. At the base of an oak, she noted the precise position of an obsidian fragment that might have been an arrowhead. Later, she reported it to the Karuk’s staff archaeologist, who investigated to determine whether a fire could disturb any such artifacts on the land—it wouldn’t. A hundred yards away, Colegrove-Powell picked up acorns bored by weevils. “When you burn the underbrush, there won’t be so many bugs,” she says.

Bringing back traditional foods like acorns is more than a sentimental concern for the tribes living along the Klamath River. The small grocery stores in the towns there stock mostly packaged goods. In a survey of these tribes, about a quarter of the respondents said that their households never or rarely had access to the healthy foods they desired. A similar proportion said they ran out of money for groceries at least once a month. Eighty-three percent of the respondents had eaten traditional foods such as acorns, matsutake mushrooms, and elderberries in the past year, and almost all said that they would like more access to them. Lisa Hillman, a coauthor of the study that generated the survey, managed a food security program for the Karuk Tribe. She says that hunting and fishing regulations make it hard to obtain foods such as deer and fresh-caught salmon. “We could not offer meat to the people.”

The Karuk’s traditional approach to land management takes into consideration not only how to make edible plants thrive but also how to nourish game, says Hillman. A good acorn harvest could benefit ducks, turkeys, quail, bears, deer, and many other animals. Clearing out underbrush facilitates hunting, too.

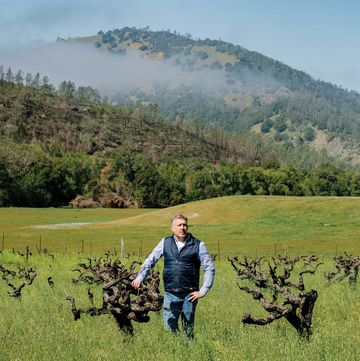

These days, in choosing where and how to burn, the tribe and its collaborators are relying on forecasts provided by the National Weather Service and mapping done with aerial photographs, computers, and lasers. But they are also using knowledge passed down among the Karuk in stories and rituals. “A lot of people say the knowledge is lost, but it’s not,” says Bill Tripp, the deputy director of eco-cultural revitalization for the Karuk Tribe’s Department of Natural Resources. “It’s in our ceremonies. We just need to extract it.”

He cites the Deerskin Dance, in which dancers manipulate deer pelts on high poles. The dance takes place biannually and rotates among locations around Orleans, California, where the tribe is based. This rotation serves as a reminder that prescribed burning should also be done on a rotating schedule, with some areas burned more frequently than others, optimizing production of food for both people and animals as well as materials for basketry and fishing nets.

In some cases, Karuk knowledge may exceed the precision of Western-trained ecologists, Tripp says. For example, a combination of state and federal regulations effectively prohibit burnings from February through June in areas where the threatened northern spotted owl might be nesting. But tribal tradition holds that weather conditions provide a narrow window of time during that season when a prescribed fire can reduce fuel in the forest—preventing a disastrous wildfire later—without generating enough smoke to harm the owls.

LET IT BURN

The Karuk enjoy the advantage of living in a sparsely populated northern part of the state that they controlled well into the 19th century. Over the past several decades, they have worked patiently to amass or gain access to parcels of land. For the TREX prescribed burning last fall, the Karuk Tribe and collaborators from nonprofit organizations negotiated with Cal Fire, the U.S. Forest Service, other agencies, and landowners for the opportunity to set fires in national forests and on private property.

The participants included members of multiple California tribes, firefighters, ecologists, archaeologists, biologists, geographers, and meteorologists from as far away as Spain. Most of those planning to set fires had to pass an “arduous pack test”: hiking three miles carrying 45 pounds in 45 minutes.

Then they camped out in Orleans for 12 days, sharing meals and swapping stories at night, training and preparing by day. Aware of how costly a mistake could prove, they took up chain saws, rakes, and shovels, cutting firebreaks, positioning water tanks and hoses, learning to watch for artifacts, and clearing brush. They monitored the weather, anticipation building toward the moment when they would stream a little bit of diesel from their drip torches.

When that moment came, orange flames shot up and smoke rose into the canopy. Following in the steps of her ancestors, Colegrove-Powell rejoiced.•

Laird Harrison lives in Oakland. He is working on a novel set partly in prehistoric California.