Originally published in the September 2011 issue.

This story needed an ending before it could find its first sentence. So please forgive me for delivering it ten years overdue.

Maybe it shouldn't have been so hard to write. Looking back, it had everything: merriment, adventure, and a journey to the top of the world. It contained a crash into ground zero on one of the darkest days in America's history and a search for fulfillment afterward. Yet for ten years, the words were trapped inside me and I couldn't get them out.

We all know the feeling of wanting to do something so well and so badly that we try too hard and can't do it at all. In the end, though, there's no trick to being yourself. So I'm simply going to tell this story the way it happened.

It started fourteen years ago, when a new editor was hired to guide Esquire. The magazine was in distress. You might find only a dozen pages of advertising in an issue, and most of them were pitching hair-replacement schemes and promises to resurrect lost sex drive. The new editor called upon a group of writers whom he'd assembled over the years to join him.

He was on a mission to resurrect a great American magazine, and he wanted good ideas. One of mine was to become the Perfect Man. The concept was to identify the subjects every man should know, and then have experts in each field show me how to master them. I was certainly up for the task. The only reason I call myself the Perfect Man, I used to joke, is that I have so many flaws to correct.

The idea turned into a monthly column, and what a blast it was. The legendary Jack LaLanne showed me how to get in shape and eat right. I learned how to project my voice from boxing announcer Michael Buffer; how to smoke ribs at the Jack Daniel's World Championship Invitational Barbecue; how to walk with grace from a Victoria's Secret model; how to prolong my orgasms from specialists in tantric sex. (My wife is eternally grateful.) The last area I poked my nose into was wine.

Wine makes a lot of men uncomfortable. It's not as if sweat would bubble above my upper lip every time a waiter handed me a wine list. But I always felt uncertain and small in those moments, especially if I was taking out a woman or hosting a group. It was much easier to crack open a beer and mock snooty wine drinkers for their full-bodied aromatic claptrap than it was to admit I didn't have a clue. But in wine, you pay for your ignorance. A haughty waiter can roll his eyes and make you feel smaller than a raisin. A fast-talking one can chump you into ordering a bottle that will launch the check into the stratosphere.

Anyway, the editor generously sent me off to wine school to finalize my education in self-improvement. In return, I agreed to showcase what I learned by becoming the guy who recommends wine to diners at an upscale restaurant. The sommelier. Then I'd write a story that would show how, with a little effort, any man could feel comfortable around wine.

The Windows on the World Wine School, the best in the city, was down the corridor from the famous restaurant by that name, at the top of the World Trade Center. The elevator took fifty-eight seconds to reach the 107th floor, and you could always tell who was taking the ride for the first time. Halfway up, everybody's stomach did the same sudden somersault, and the rookies would grasp in panic for support ... and then return the smiles of the vets remembering their own first trip.

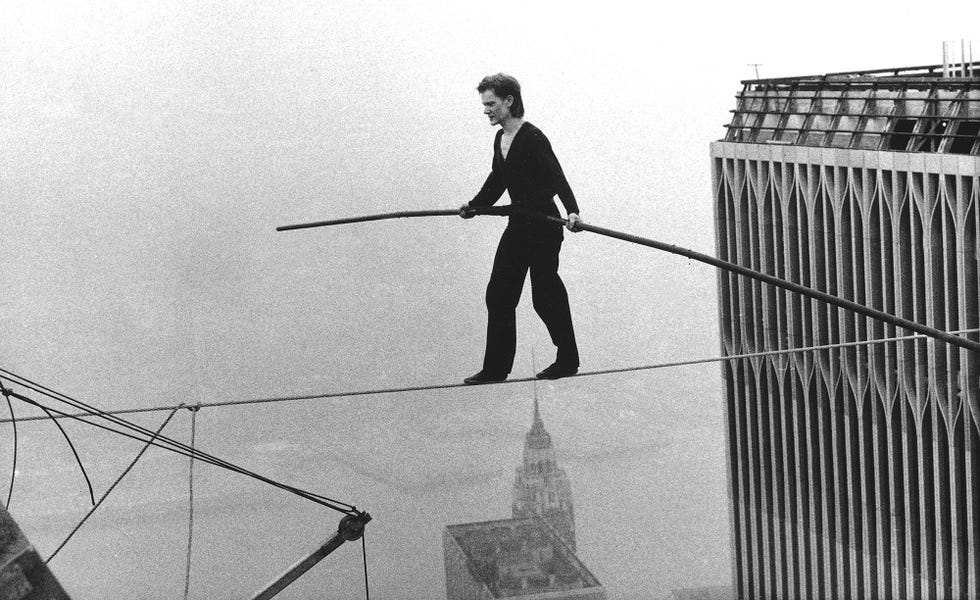

The classroom was a ballroom filled with tables topped with columns of empty wineglasses. Everyone who entered wandered first to the long stretch of floor-to-ceiling windows. On a sunny day or moonlit night, the view of lower Manhattan from Windows on the World was like the first time you heard Frank Sinatra singing "New York, New York." It was amusing to look down at helicopters. Just thinking about the acrobat who once walked a three-quarter-inch steel cable between the tops of the Twin Towers made you wonder what wasn't possible. You had to hand it to the architect who envisioned that millions of people would travel millions of miles to dine some 1,300 feet above sea level. For a time, no restaurant in the United States took in more money, and no restaurant on the planet sold more wine.

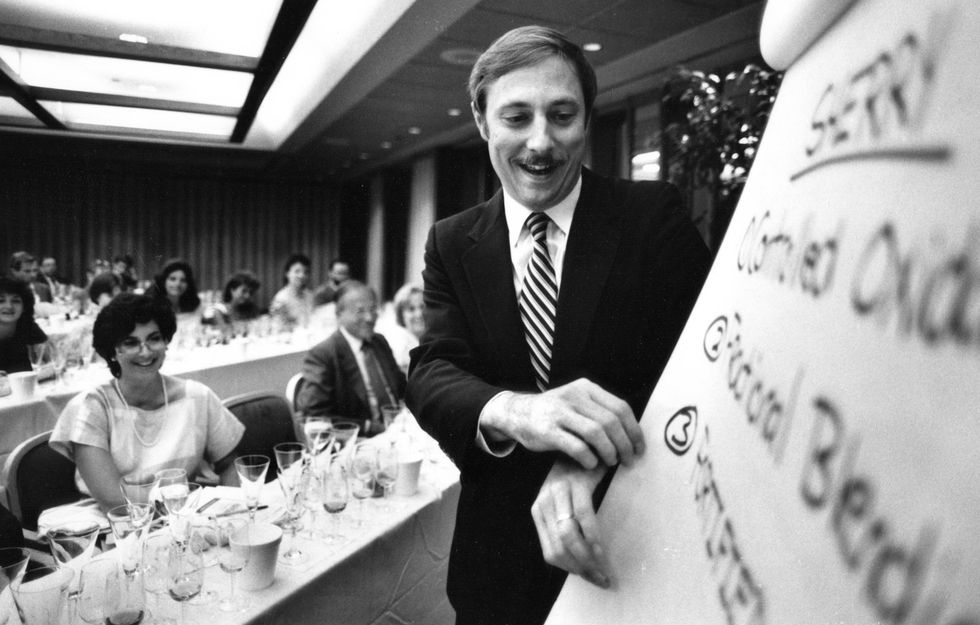

The guy who ran the wine school was, and still is, sort of a cross between a stand-up comic and Monty Hall from Let's Make a Deal. His name is Kevin Zraly. I could never describe all that Zraly passed on during this eight-week course in 1999. Time and a storm has eroded most of the memories. But a writer who prided himself on never keeping a diary once told me that "the good shit sticks." Nine years later, I'm left with what stuck.

So here's a story that gets to Zraly's core: As a young man, Kevin was interviewed by the legendary restaurateur Joe Baum for the position of cellar master at Windows. Baum's first question was "So, Kevin, what can you tell me about wine?"

Now, that may appear to be a casual way to start an interview, but it's a terrifying question for an applicant who's depending on the answer to get a job. The question's too big. What possible answer is there?

"I like to drink it," Zraly replied.

He knew how to shrink the complex to the simple—a good quality to have if you're going to introduce people to wine. For example, he'd point to the three major varieties of white wine—Riesling, sauvignon blanc, and chardonnay—and ask you to visualize them as skim milk, whole milk, and cream. Before you'd even tasted the wines, you had an idea of where they stood from light to heavy. Then he did the same for reds. Pinot noir: skim milk. Merlot: whole milk. Cabernet sauvignon: cream. With that information alone, you could go into a restaurant, order a thick sirloin, and know that it was wiser to muscle up to the steak with a hearty cabernet than a willowy Riesling.

Classes passed quickly, and the wines that Zraly exposed us to began to work their magic. They encouraged us to go out and seek, to lose ourselves in a world that no one person could ever fully explore.

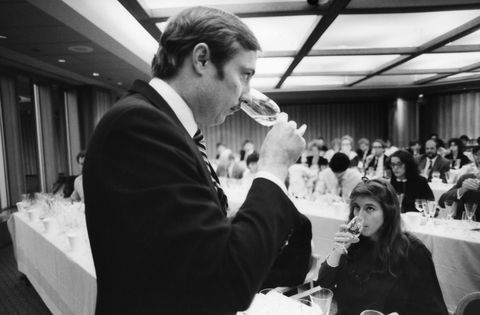

The first day I got lost was a memorable one. April 20, 1999. When people who loved wine heard that I was attempting to become a sommelier, they immediately took me in as a long-lost brother. I had been invited to a wine-tasting lunch at the great restaurant Daniel, where eleven wines from Chateau Lagrange, in the French region of Bordeaux, were to be poured. One of the first things you need to know in order to function at a tasting is how to roll the wine around your mouth, spit it into a bucket, and define the flavors left behind. This allows you to discern the different styles and tastes without getting drunk. Unfortunately, novice that I was, I hadn't quite figured out how to spit and taste by the time of that lunch. So I drank all eleven glasses. Then, in a warm fog, I walked downtown to class at Windows on the World, where another dozen wines were poured, then drifted off to dinner with a winemaker, during which several more bottles were opened. It was like the best day of school you could imagine, when you also discover you have an enormous family that you never knew about. The Brotherhood of the Grape, someone called it.

I learned, I laughed, I embraced. It was one of those days that end with you peeling off your clothes, lying down, and drifting off to sleep happy to be alive. And I did just that, completely oblivious to the fact that early that same day, twelve students and a teacher were gunned down at Columbine High School.

There's only one way to know which bottle of wine to order at a restaurant or buy for a friend: taste it.

Problem is, how do you taste them all? Something like sixty-five hundred French wines alone can be purchased in the United States. Tens of thousands of labels are imported from Italy, Portugal, Spain, Germany, Hungary, Austria, New Zealand, South Africa, Greece, Argentina, and New Zealand. Wine is produced in all fifty states.

Where would you start? There are good answers to this question. I was most impressed with the shortest: Vinexpo.

Every other year in Bordeaux, winemakers from around the world pour their juice for more than fifty thousand buyers to sample. By brazenly promising to taste nearly every wine on the planet over a few short days, I wrangled some expense money from the editor and jetted off.

My bravado evaporated the moment I stepped into the convention center and felt the bottom of my jaw dangling beneath my balls. I faced a hall that was—no exaggeration—a mile long and two football fields wide. I'm usually the type of guy who never says no unless you ask me if I've had enough. But this ... was almost too much.

I tasted, spit, and scribbled in a notepad as if I were one of the chosen few, the Jedi who could taste a wine blindfolded and tell you everything about it. But it wasn't long before I was lost in the maze. My first day would've ended without a memory of a single wine if I hadn't stumbled upon a man named Anthony Dias Blue. The pourers treated him as if he were a celebrity, because when Blue highlights a wine in the press, that label is elevated above tens of thousands of competitors. As I followed him around, I noticed that when certain pourers saw Blue, they reached under the table and pulled out bottles the rest of us weren't getting. I glued myself to his side and the pourers had no choice but to show good etiquette and fill my glass beside his.

That was how I found out about La Turque, a wine made by Guigal in the Rhône region in France. Tasting a $400 wine when you've been cutting your teeth on $20 bottles will widen your eyes. But for me, this wine was bigger than that. La Turque opened my ears. It made me hear music. As I drank, Edith Piaf was singing "No Regrets" right out of that glass, and believe me, she was in her prime.

That might sound a little loopy. But people have found crazier ways to describe the taste of wine. I've heard praise for the "barnyard odors" in a glass of burgundy. A sommelier once asked me if I had picked up "brussels sprouts" in the bouquet of a red wine from Chile. And a wine magazine editor once assured me that there was "a hint of Tasmanian black pepper" (my italics) in a glass of Shiraz. I could never get excited talking up brussels sprouts, and describing wine with adjectives like metallic, nutty, tart, floral, and woody just wasn't me. So I began to correlate wine with music, and to this day the melodies have stayed with me.

As the months passed, I scribbled comparisons between wines and songs on scraps of paper constantly. I tossed these notes in a box along with pictures of some of the many wineries I visited when the opportunities arose and I could coax more expense money out of the editor.

Ella Fitzgerald singing scat is wonderful champagne.

Luciano Pavarotti is a great Barolo.

Pick up a Robert Weil Riesling Auslese and you might hear Sade singing "The Sweetest Taboo."

I once observed a woman in a supermarket checkout line buying a couple of bottles of mass-market California merlot and asked her if, by chance, she happened to like the music of Barry Manilow. "I do," she replied. "How did you know?"

I once brought my wine-to-music theory to the home of Monte Lipman, chairman of Universal Republic Records, and it wasn't long before everyone was discovering Joe Jackson's voice in a glass of fine California chardonnay.

The beauty of learning wine by music is that you're never ignorant. You have an opinion that's as good as anyone else's. If a sommelier brings you a wine list and you have no idea what to order, you can always say, "We'd like a bottle of Louie Armstrong singing 'What a Wonderful World.'" Suddenly, the pressure has been reversed. (He's right on track if he brings you a bottle of Lalou Bize-Leroy burgundy.) Stick to the music and you'll never get bogged down in a conversation with some wine geek that includes the phrase malolactic fermentation.

But there is some technique involved in tasting. You can help your ears tune in to the music by getting the most out of your nose and tongue. What you want to do is pick up your wineglass by the stem (not the bowl) and swirl. The air will turn up the volume on the aroma. There are chemical reasons for this, but maybe it's easier to understand by imagining yourself on a hot, listless day. In the distance there's a guy barbecuing, but he's too far away for you to see or smell a thing. If, however, a strong wind were to blow in your direction, your nostrils might twitch at the airborne molecules of 'cue.

So stick your nose in that glass and inhale. But equally crucial are the taste buds aligning the insides of your mouth. Don't gulp the juice straight down—the flavors will zoom by. Let the wine coat the inside of your mouth before you swallow, and you'll soon be tuned in to the music.

Whether you like a certain song is up to you. But if the bass in a song were so overpowering that it ran roughshod over the melody or the lyrics, everybody would know something was wrong. It's no different with wine. The winemaker is like a record producer looking for harmony and balance in flavor. The acidity in a glass of New Zealand sauvignon blanc should not squash the fruit. Nor should the tannins that come off red grape skins, the ones that bring a dry sensation to your palate, block out the fruit in a cabernet sauvignon.

There are critics who score wines numerically, as if each bottle were a math test. But just as a song becomes magical when it coincides with a moment that has meaning in your life, a wine doesn't need ninety-seven points to be fantastic. Meet the woman you want to spend the rest of your life with and the $12 pinot noir you raised when you first looked into her eyes becomes priceless.

The first night I was allowed to walk the floor as an apprentice sommelier at Windows on the World, I saw a three-hundred-pound man in his best suit get down on his knee in the middle of the dining room and propose to his fiancée. When she accepted and they embraced, there was applause all around.

That's what made the place special. This was a restaurant that got a thousand calls for reservations each day, had twenty-five hundred chairs and seventy cooks. Seven hundred pounds of shrimp were served each week, and three thousand forks were washed each day. And yet, despite the restaurant's size and the enormous volume of food that left the kitchen, the staff made every diner feel like the experience was not only intimate but uniquely his or her own. The woman who accepted the proposal that night glowed like a queen. It would be my job to help maintain that glow.

I had the good fortune to be assigned to one of the Jedi. Windows on the World's Andrea Immer had won a highly competitive contest in 1997 to be crowned the best sommelier in America. She was five feet two inches of pixie and pure grace, and the confidence she had on the floor reminded you of the way a great athlete owns a field. You got the sense that diners returned just to see her.

When she asked if I'd brought along a waiter's corkscrew, I produced a sleek one that had been given to me as a gift and had the look of a new Jaguar driving out of the showroom. "I'll bet the blade is really sharp," she said. "You might want to start out with one that's been used."

There are many skills that a great sommelier must master. But to me, the most important is the ability to remove the fear from diners who know little or nothing about wine. People have good reason to be nervous. Maybe it's the link to royalty in the past, but wine has a way of bringing out that I'm better than you quality in people you wouldn't want to have a drink with. But mostly it's the prices that keep people on edge.

It may be strange to say this now, but when it came to wine, Windows was the safest place in the world to be. You'd never be made to feel uncomfortable if you didn't pronounce a wine correctly. You'd never be recommended a wine just because it wasn't selling and the manager wanted it out the door. You'd never be chumped into buying a pricey one to jack up the bill. Andrea had the ability to magically intuit how much you'd feel comfortable spending and then find a way to match your food with the best wine your money could buy. Her goal, it seemed, was to prove you could love wine as much as she did.

As I followed Andrea around the floor, I was amazed at how her passion merged with precision. There was a certain way the wine bottle was to be carried from the cellar, the bottom grasped in the hand, the body cradled like a football inside the forearm. There was a correct way to introduce a wine by holding the label in front of the taster and reciting its name, region, country, and vintage. A correct way to open a bottle with the waiter's corkscrew, circumnavigating the knife blade around the lower lip and then using the blade to peel the foil off over the top of the cork. Chardonnay had to be poured to exactly the fattest part of the glass, allowing room for the drinker to swirl without spilling. It would take me pages to describe all the rules and procedures, but they contributed to something special, because diners were at the same time made to relax and feel like royalty.

Andrea made it all look so easy that when she asked me if I'd like to try serving a table myself, I accepted—without bothering to tell her that I had never removed a cork with a waiter's corkscrew.

My first table was a group of guys who were ordering steaks and laughing so loudly that it didn't seem possible to screw up. The table reminded me of an Australian party, so I recommended a Shiraz from Down Under that wailed like Tina Turner. I circled the corkscrew's blade around the foil covering the lip, but when I went to strip the foil over the top of the cork, I fumbled and the sharp new blade sliced into my thumb and sent blood spurting.

"You okay?" Andrea called from outside the door of the men's room as I rinsed off my bloody palm. It was beyond embarrassing.

I stared in the mirror, shook my head, and tried to smile. An acrobat had once lain down on his back on a steel cable between the Twin Towers a quarter of a mile above the sidewalk. The Perfect Man couldn't even open a bottle of wine at the same height without bloodying himself.

There was never a day that I entered the World Trade Center when I didn't think about Philippe Petit's tightrope walk between the towers.

Even now, after watching snippets of it hundreds of times on YouTube, it still gives me thrills. The walk was not sanctioned, and there was no safety net. Petit spent six years in secretive planning, observing the towers as they came up and posing as a construction worker and a journalist to take measurements and check out the wind currents. Early on the morning of August 7, 1974, he and his posse hid in the World Trade Center and used a crossbow to first shoot fishing line across the gap between the towers, then pull successively thicker lengths of rope across that could support the cable.

At 7:15 a.m., after the 450-pound cable had been stretched taut between the towers, he stepped out. The sonavabitch didn't just walk. He danced. At times, both of his feet bounded off the cable. He bowed on a knee. He lay on his back with his balancing pole balanced on his chest, and relaxed as if he were in the grass of Central Park.

When he was asked later why he did it, he replied, "If I see three oranges, I have to juggle. And if I see two towers, I have to walk."

I took inspiration from his preparation, showing up early for business conferences so I could practice opening dozens of bottles consecutively with my waiter's corkscrew until I could do it in my sleep. I learned to discreetly point to prices on the menu as I spoke about wines so the host could let me know if my recommendations were within his or her budget without ever having to mention the cost. I wanted to connect every diner with the grandeur of the journey from wine dunce to sommelier. I wanted you to understand what it was like to try to drink every wine at Vinexpo and bump into Edith Piaf.

Sometimes I got carried away with diners who knew more than a little about wine, entering prolonged discussions over exactly which hard-driving California cab could release "Freebird" in their souls. In times like those, the general manager, Glenn Vogt, would call me over, put his arm around me, and let me know that it was great to see an entire table looking at the wine list as if it were a jukebox, but in the meantime four tables had been seated and the diners appeared to be very thirsty.

It was time to step out on my own. Glenn and the chef, Michael Lomonaco, knew just the right place to hang the high wire.

Wild Blue was a romantic restaurant set alongside Windows on the World. It had the same floor-to-ceiling windows, but it was not a tourist attraction. It was an intimate dining room that New Yorkers knew about and returned to because it was the place where Lomonaco had thrown his heart and soul. It was his home within Windows, which made me proud when he made it mine.

My first evening as the sommelier was a Thursday night in May, 2001. The first seating was a couple celebrating their twentieth anniversary. The husband was a friend of mine, but his wife had never seen my face and therefore had no idea that I knew who she was. I had them seated at a table overlooking the necklace of lights on a bridge straddling the East River. Then I approached them in a suit tailored especially for the evening with a bottle cradled against my chest.

"Good evening," I said. "On the occasion of your anniversary, all of us at Windows on the World would like to present you with a taste of Lordeaux champagne. It is served at the Assemblée Nationale in France and is ordinarily unavailable in the United States. Never before has it been poured at these heights, and never shall it be poured here again." The wife knew little about champagne, but she understood something much deeper, and as she looked at her husband, her eyes welled up.

If on that night I possessed one-trillionth the audacity of Philippe Petit on the high wire, it still was big juice. I simply had no fear of wine. If you asked me about the fifteen hundred wines on the Windows list, I could talk to you from amarone to zinfandel. Pick your music and I'd pour. I even found humor in my missteps. When I spilled a few drops on a table, I apologized with gusto. "That is unforgivable! Let me bring you another bottle on the house!"

"Hey," called a guy at the next table. "Why don't you spill some here!"

I spread such joy on that evening that people actually took money from their wallets and slid it into the palm of my hand as they shook to say goodbye. Even as I protested—"No, you don't understand, that's not why I'm doing this"—they insisted, squeezing my palm shut, imploring, "Take it, please."

A week later, a woman whom I served that night came back with some friends and asked in all seriousness, "Is Cal working tonight?"

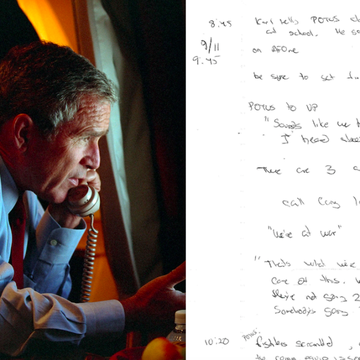

Perhaps I should have started writing the story the following day. But there was no deadline, I was occupied with other work, and I went on vacation over the summer. I figured I'd clear out time in September.

I didn't know any of the seventy-three staff workers at Windows on the World who died on September 11 after the hijacked plane smashed into the North Tower. I didn't know any of the waiters who were serving seventy-one guests at a technology conference breakfast. I didn't know any of the people who chose to jump rather than choke and burn, nor any of the firemen who went up when everybody else was coming down, nor any of the more than three thousand who perished. I do know a man who was in the bathroom on the eighty-first floor when the airliner struck, who got down the stairwell in time to see Tower 2 imploding in the reflection off the windows of the Millennium Hotel across the street, and who dove for cover screaming the names of his wife and son as the weight of the World Trade Center fell on his head. When my friend Michael described the experience, we both knew that there was no way he could even begin to convey the depth of emotions he'd passed through on that day. So there's very little reason to bring up my feelings—especially since I was five hundred miles away. I can tell you I felt the need to be there.

A few days later, at dusk, a friend of a friend managed to get me on a National Guard Humvee that toured the site. Even after all the images I'd seen on television, it was unrecognizable. I understood why people in New York who were watching the towers fall on television had left their living rooms to watch it from their balconies or windows or rooftops, just to confirm that it was truly happening.

We drove through military checkpoints, police checkpoints, fire-department checkpoints. I stared at the monumental tangle of steel and concrete and realized the hijackers had planned to kill with the same intense detail that Philippe Petit had employed to make our spirits soar.

For hours, we toured the sight in virtual silence. At one point, we passed some graffiti that read: O BIN, YOU DONE FUCKED UP.

As my friend Michael had run down city streets covered in dust consisting of the remains of people who'd been disintegrated, he tried to grasp some meaning from what was happening. This was all part of a pattern of human cruelty and killing that has gone on since the beginning of time, he told himself. He just happened to be very close to this one.

Some part of me was not the same as it was on 9/10. It would have been very easy for me to kill anyone attached to this in the slightest way.

The evening turned into morning and I never did get my balance. When I saw a parking garage filled with cars covered with that same gray dust, I turned to the National Guard captain and foolishly asked, "Why don't people come and get their cars?"

"Cal," the captain said, putting a hand on my shoulder to balance me and leaving it there for a while. "A lot of those cars don't have owners anymore."

I can't be sure that wine has ever tasted the same to me.

Not long after, a benefit was organized for the families of those who'd worked and lost their lives at Windows on the World. Elite wineries in California donated cases of their best stuff to be auctioned off. The city's great chefs volunteered to cook for the occasion at Robert DeNiro's restaurant, Tribeca Grill. New York's finest sommeliers signed on to pour. Glenn Vogt called and asked me if I'd stand in as the sommelier of Wild Blue. Glenn had arrived at the World Trade Center the morning of 9/11 to see bodies and debris hurtling down from the sky. Michael Lomonaco would be at the benefit only because he stopped to get a pair of eyeglasses on 9/11, delaying his regular arrival for the fifty-eight-second elevator ride up to 107.

At the benefit I poured fabulous wines from Screaming Eagle, Harlan Estate, Colgin Cellars, Bryant Family Vineyard, and Sine Qua Non, all the while thinking about the Muslim waiter at Windows who'd died in the carnage and whose wife gave birth to his son the following day.

Hundreds of thousands of dollars were raised. Toward the end of the evening, the chefs were announced to great applause. Then the sommeliers. As my name was called out with a few others from Windows on the World, a few diners stepped out of their chairs to make it a standing ovation. Waves of emotion ran through me, incredible pride to have been touched by Windows, but also the feeling you get when you bite into a rotten pear. Yes, the evening was all about lifting spirits. But there was no escaping in that instant what an imposter I was. I was no sommelier. I had not lost my colleagues and my livelihood. I was a writer—and even worse, a writer who, at the moment, couldn't write.

I'd spent many 3:00 a.m.'s staring at a blank computer screen searching for a first sentence. There was none. Nor was there a last. Everything in the middle was wine bottles falling end over end through space as bodies hurled by into the twisted jumble of wreckage.

Months later, I went to interview the chef Mario Batali for another story, and I told him about my experience. If anyone would have a response to the one question I wanted answered, it would be Mario, for at heart he was a creator who knew how to bring very different ingredients together to make his food sing. "Is it possible," I asked, "to write a story that balances the fun I had discovering wine with the horror of 9/11?"

He was silent for a moment, then he slowly shook his head back and forth. "No. You'll never be able to do it, " he said. And then he paused and added, "but you've got to."

The editor who'd backed my journey didn't say a word—which only made it worse. After handing me one of the best years of my life and seeing the conflict it had smashed into, we both knew he was hoping for something extraordinary.

I tried to jump-start the story like a dead battery by going off on my own to Portugal to do something I'd dreamed of: turning grapes into wine with my bare feet. Technology has made winemaking more efficient throughout the world, but the best ports are still made the old-fashioned way. After the grapes are picked, they're dropped into granite troughs called lagars that hold about two thousand gallons of juice. In the evenings, the pickers methodically march for a couple of hours. Then a free-for-all called liberdade erupts and a carnival in grape juice begins. I stepped into the lagar at Fonseca, marched for hours, and then threw myself into the party. We stamped our grape-stained handprints on each other's shirts and spun dizzily all night. When liberdade came to a close, one of the Portuguese grape pickers asked me where I was from. "New York," I said. He blinked, said, "World Trade Center," and came forward to embrace me. The woman next to him joined him in the embrace, as did the man behind her. The embrace grew larger and larger, men and women forming a collective hug around me up to our thighs in grape juice.

And still, the world's understanding did not give me enough understanding to write. Nothing came, and in my guilt I'd find myself stammering to the editor that something soon would. But I knew the reality. I took the box of wine notes in my office down to the basement and buried it. My lies made my guilt feel like betrayal.

More time passed. In 2004, the hilarious movie Sideways, about two guys on a road trip through California wine country, came out to great fanfare. Wine bars started sprouting all over America. More and more people were becoming aware of wine and less afraid of it. The editor called me in to tell me that the story might no longer be relevant, perhaps a last-ditch attempt to wrench it out of me. I went to my basement to dredge up my wine notes and found that they had been soaked by a rainstorm and were now black with mold.

The fifth anniversary of 9/11 arrived and an extraordinary magazine cover appeared in my mailbox: an illustration of Philippe Petit with his long balancing pole on an empty white background. There was no tightrope. There were no Twin Towers. He was trying to balance himself on nothingness. Which is exactly what writing this story would be like—trying to walk a tightrope that didn't have any rope.

Time had only made the world more bewildering. There was a war declared on a country that didn't attack us. The world that had hugged me in a Portuguese wine trough had now seen a photo of a smiling American soldier holding a leash that circled around the neck of a naked Iraqi in a prison. Once, in North Carolina, an all-American eight-year-old kid I was interviewing told me about arguments he'd had with classmates who adamantly insisted that President Bush had secretly masterminded the attacks on 9/11. There was an economic meltdown. An opening appeared for a man with black skin to demand change and be elected president. Navy Seals finished off bin Laden. Dictators were overthrown in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, while the tallest building in the world was being constructed in the Middle East and the U.S. shuddered as it reached its debt limit.

The world was evolving into a different place because of 9/11. Everything that happens for the rest of this century will stem from that day, just as September 11 came out of everything that preceded it.

I had walked in the carnage of the most important moment of my lifetime. A writer with nothing to say. And how important was that, anyway, when I thought of the thousands of kids without parents?

When the ball descended and the clock struck midnight to announce the beginning of 2008, I stood and cheered with my family in the middle of Times Square. Millions of people had been neatly arranged in blocks by the police department throughout the day, and my three children ran with their friends amongst the jubilant crowd with happy abandon. There had not been an attack on our soil since 9/11. I looked around at the police presence and the sense of organization, and I swear in that moment it felt like Times Square was the safest place on earth. Could I have imagined that on 9/12? No, I'd never be able to make sense of it all. Something inside me stopped trying.

If it was death that took the story away from me, then it was death that brought it back to life. I was eating dinner with a group that included a woman whose husband had passed away. She'd spent a good amount of time on her own and concluded that she was ready for another partner.

She explained how difficult the transition was. Having been married for years, she felt uncertain, didn't even know how or where to begin looking.

As she spoke, an image came to my mind of Kevin Zraly proudly announcing how his Windows on the World wine class had been the meeting ground for more than a dozen marriages and created quite a few children.

"Enroll in a wine class," I said.

It was a sensible suggestion. You can get a good glimpse of somebody's character simply by talking about wine, and if it flies from there, it's destiny. But the instant I made the suggestion, I realized that something huge had happened. For the first time in years, I once again saw wine in terms of possibility and growth. I had come to a new beginning—which meant that this story had an end.

Not long thereafter, I sat at a hotel bar with a blank notebook and began to trace all the grape stains backward to the day in 1999 when I first stepped into the elevator in the lobby of the World Trade Center.

The more I thought, the more I realized how absurd it was to think that this ever could have been a simple, merry story. Life is just not that way, and nobody's ever going to be perfect. The world is balanced just like the finest wines. Since 9/11, my life had been touched by births, graduations, weddings, anniversaries, and amazing little moments that make you grateful to be alive, as surely as it had brushed up against illness, cruelty, murder, profound sadness, and death. Wine is simply here to help us celebrate the joy as well as push us past the tragedy. "Give me wine to wash me clean from the weather-stains of care." Ralph Waldo Emerson got that right.

As I sat at that bar drifting back in time, a waiter approached the bartender carrying a glass of a sweet white wine from Italy called vin santo.

"We have a complaint that it's not good," the waiter said, pushing the glass toward the bartender.

The bartender was young, just out of college. He poured a fresh glass from the bottle, took a taste, and looked uncertain.

"Let me try," I said. There was an authority in my voice that surprised even me, and the bartender poured me a taste and pushed it forward. I swirled the glass the way Zraly taught me and guessed from the aroma that the bottle had been open for a while and the exposure to air had distorted the wine.

"That's correct, it's not right," I said upon tasting. "Open a new bottle and pour a fresh glass."

The bartender opened a new bottle, poured the glass, sent it off with the waiter, and turned back to me. He told me he wasn't really a bartender but an aspiring singer, that as a high school student he had once sung "Ave Maria" for Pope John Paul II in the Vatican.

"That wine wasn't that bad," he said. "How were you so certain it was no good?"

"If you sang for the Pope, you know all you need to know," I said. "Taste it again. This time, listen to the music in it. You'll see how the music's right, right, right—then, at the very end, there's a note that's off-key."

He put the glass to his lips, ran the wine around his palate the way I told him, swallowed, and a smile slowly lit up his face. "Yeah," he said, nodding. "Yeah. I get it."