The Twisted Life of Clippy

The blank screen was already intimidating enough. Then, out of nowhere, an incorporeal know-it-all popped up to make us feel even worse about the novel notion of word processing in the mid-’90s. “It looks like you’re writing a letter,” a googly-eyed, caterpillar-browed paperclip in Microsoft Word observed when we may or may not have been trying to write a letter. The metallic office supply bounced around the margins of documents and never stopped looking over our shoulders, even as it blinked back at us impatiently. “Would you like help?”

Many users found its polite but presumptuous suggestions invasive, obnoxious, and creepy. Almost immediately, computer geeks and neophytes panned it. Microsoft banished it. Time labeled it one of the 50 worst inventions ever. But nearly three decades after its genesis at the Redmond tech giant, Clippit—better known as Clippy—improbably lives on.

Last year, Microsoft officially revived the Office Assistant that debuted in Office 97. The character replaced a plain old paperclip in Microsoft 365 to help liven up the company’s emojis and indulge a social media outpouring. Clippy can now permanently live in Word files, Outlook emails, or other common workplace apps. In one of the company’s Teams backgrounds, the paperclip hovers above yellow legal pad paper on a pedestal in a cement-walled basement, seemingly exiled to the dungeon of bad tech ideas.

Though coding circles treated Clippy like New Coke, pop culture never quite quit the retired paperclip. When Darryl Philbin needed help with a resume in the season seven finale of The Office, he pined for Clippy. When users couldn’t grasp Pied Piper’s platform in Silicon Valley, the startup begrudgingly turned to a virtual assistant named “Pipey.” When Seth Meyers needed a dash of comic relief amid news that a PowerPoint may have spurred the Capitol insurrection last year, he joked Congress would “have to subpoena Clippy.” Saturday Night Live nodded to this nagging cultural endurance in a sketch six years earlier. As J.K. Simmons tries to type a letter to a friend on Microsoft Word, a shimmying push pin, “Pushie,” prods him with suggestions. Then Simmons’s character discovers a “Murder Pushie” option. Yet, the actor can’t bring himself to click it.

Though he was skeptical of the Office Assistant, Bill Gates can't claim too much distance from its development.

Image: REUTERS / Alamy Stock Photo

Nerd culture’s attachment to Clippy is even stronger, manifesting most frequently on social media and dark corners of the internet. An erotic short story, “Conquered by Clippy,” reveals perhaps the wildest level of obsession (“‘assist me deeper’”). Viral fan art renders the sentient silver fastener as everything from mildly impressed to pregnant. The assistant’s once-grating command bubble and syntax is basically Mad Libs for passive aggressive memes, including those aimed at the sort of existential conundrums posed by tech today. “It looks like you’re writing unsubstantiated nonsense,” a popular one begins. “Would you like to turn on all-caps?”

These days, an annoying Word creature might seem eminently tolerable compared to the ghouls on Twitter. Now that Alexa’s in our bedroom and Siri’s in our hand, Clippy’s a throwback to what seems like a more benign digital age.

But to those involved, directly and indirectly, with what’s been called one of the worst user interface rollouts in tech history, Clippy’s comeback is varying degrees of bewildering and vindicating. Especially after what happened to Bob.

Behind a one-way mirror in the bowels of Microsoft’s Redmond campus, Karen Fries watched yet another volunteer cry.

The wife of a colleague had offered to test Microsoft Publisher, the desktop application that debuted in 1991. Back then, the company still leaned on friends and family as guinea pigs for its products. Managers and developers eyed subjects like lab investigators from behind the glass, observing their every cursor move. Only about 15 percent of households owned a personal computer, or PC. Even the people closest to the geeks actually building the machines feared the technology. “They’d be afraid to even move the mouse,” recalls Fries. Sometimes, they’d tear up.

Fries didn’t want people to feel stupid using computers. She wasn’t what former employees describe as a typical Microsoftie at the time: a Birkenstocked or button-downed developer with a Y chromosome. The “black sheep” in a family of engineers, Fries graduated with degrees in business and psych from the University of Washington.

In 1987, just over a decade after Bill Gates and Paul Allen founded Microsoft, she started in Redmond. Four buildings surrounded “Lake Bill” at the HQ that would transform a small farming town 15 miles east of Seattle into a big-tech hub.

On her first day, Fries shared an orientation room with Melinda French. Years later, the Duke MBA eventually known as Melinda Gates would oversee the work of Fries and others on a much-maligned software project.

Released in 1995, the suite of programs dubbed Microsoft Bob arose from all those teary-eyed trials. Microsoft had created “wizards”—the boxes that pop up with prompts, along with “next” and “finish” and “cancel” or other options, during installations and similar tasks—to help new users. But volunteers still struggled with them. “What a lot of people don’t understand is, in the ’90s, the majority of people had not touched a computer,” says Fries. “They didn’t know how a menu worked.” Fries, who’d ascended to program manager at the company, and her colleague Barry Linnett decided they would need to think outside all those dialog boxes to reach beginners.

So Linnett decided to try something wacky. For one focus group, a cartoon owl would deliver directions instead of the usual boxes. Unlike usability tests, Microsoft managers wandered the room for these sessions. At one point, a novice took Fries’s arm. He implored her to ditch the printed instructions that typically accompanied products back then. The owl was his life raft. “Just give me this,” he said.

Fries and Linnett would test scores of similar characters as “wizards” for Bob. They’d do so with the help of two star Stanford researchers. Clifford Nass and Byron Reeves were an odd couple—Nass a computing savant liable to have a chunk of cream cheese on his tie, Reeves a polished film and TV buff—but they were of the same mind about media: People’s interactions with screens were “social and natural”—as if the machines were humans. During a two-year leave from Palo Alto, they visited Redmond almost weekly as consultants with Microsoft’s internal think tank.

The team of academics and Microsoft managers settled on a dog named Rover as the default character to guide users through “Bob,” a name chosen to signal approachability. The software’s gateways to email, word processing, and a handful of other programs seemed foolproof. Users entered log-in information after clicking on a door knocker. Inside, a virtual room contained a checkbook to manage finances and a pen to write letters. Along the way, Rover offered the kind of ballooned instructions that a certain paperclip would later make infamous.

But Bob bombed. Swiftly. Trade magazines, all-powerful gatekeepers then, lampooned it as too basic.

The problem was partly technical. Bob required eight megabytes of computer memory, which few beginners owned at that point. This kept characters rudimentary. “You were asked to make a movie, basically, with a box of colored pencils,” says Reeves.

Fries acknowledges a philosophical reason, too: “I didn’t anticipate how quickly people would move off of the beginner mind.” Once people got the hang of computers, they didn’t want someone—or something—holding their hand, especially once the internet was around. By 1996, one year after its launch, Bob was history.

The backlash weighed on Fries. Another group within the company was using characters for a new Office product—the assistants weren’t necessarily the problem in Bob, the thinking went, their janky environment was. But Fries stayed away, unlike one artist who’d etch his name in tech history—and then try to erase it.

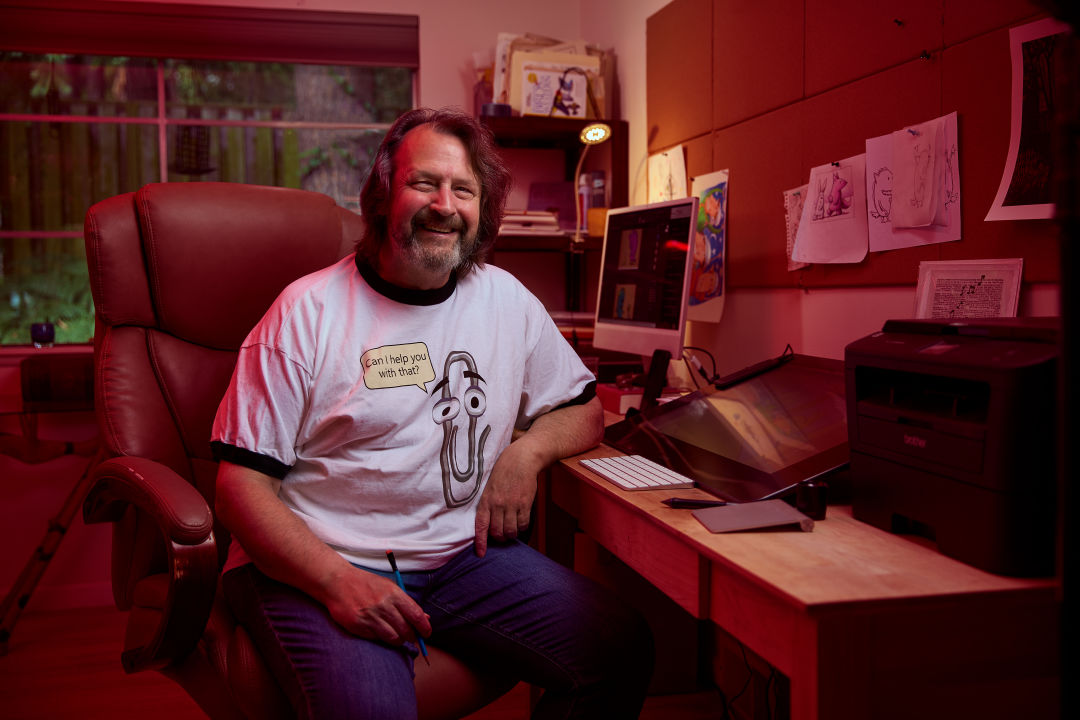

Kevan Atteberry once hid his ties to Clippy. Now it opens creative doors for the children's book author.

Image: Carlton Canary

Avert your eyes, PC stans: Clippy was born on a Mac. When Kevan Atteberry was hired to design characters for Microsoft Bob and Office 97, he’d shuttle between the company’s leafy grounds and his Bellevue studio space, where a desktop made by a certain rival awaited. Animation required using Microsoft’s proprietary software, but before hustling files over to HQ, he could tinker in his second-floor walk-up with tons of light and a landlord who never raised the rent. It was here he picked up a Ticonderoga two-and-five-tenths pencil and started outlining an infamous paperclip. Digitizing it just meant closing the blinds and booting up the Macintosh he preferred to his employer’s PCs.

“This is my original Clippy,” Atteberry says one recent morning, pulling up an image on an iMac.

The 66-year-old with Lebowski-esque locks and a beard lives in a one-story home not far from his old workspace. Bunnies abound; stuffed and painted ones top the mantel, while copies of The Velveteen Rabbit and Bunnies!!! get face-out treatment on crowded shelves.

Atteberry wrote and illustrated the latter. Money from Microsoft contracts allowed him to finally pursue his childhood dream of authoring picture books. Before he started his career as a graphic designer, the art school dropout from a Boeing family steered a forklift at a local Paccar warehouse.

Microsoft gave him a private office and the freedom to draft 20 or 30 characters for Bob. Naturally, one was a rabbit. “Hopper” made the final cut as an alternative to Rover.

Another, however, was a stapler. Atteberry dug the freedom of anthropomorphizing something inanimate. Animals came with expectations about their movements. Desk items and other objects could be as “psychedelic” as he wanted.

Set against lined yellow paper, the two-dimensional paperclip on Atteberry’s iMac is more of a cartoon than the meme of today. Groucho-like brows eventually replaced Atteberry’s original heavy lids; a bent metallic end gave Clippy a tail or hand, depending on its movement. The company called in an animator, John Michaud, to make the paperclip look more three-dimensional as he danced and dodged the mouse around the screen. But the character’s big pupils remained. Everyone from the Disney animators Microsoft consulted to Clifford Nass and Byron Reeves’s seminal book, The Media Equation, said the eyes were critical to building trust.

Generally, Atteberry’s character tested well in focus groups—the best of any assistant in some cases. Yet its massive eyes could be buggy. Some women in the cohorts deemed Clippy a man, and the constant male gaze creepy. “There were comments about how Clippy was leering,” says Roz Ho, who worked in product planning for the PowerPoint team then. When Ho raised that concern, she says the men in the room—everyone else, basically—couldn’t process it. “It really wasn’t about, like, these guys were bad guys, or anything. It was just they had a hard time picturing that feedback.”

Byron Reeves wasn’t sold on Clippy, either. The choice of a paperclip just felt too literal for a product called Office. Plus, “the worst thing about Clippy,” Reeves says, “was that he interrupted.”

“The Fucking Clown.”

That was the internal name for Clippy as Office was in development. Sam Hobson, a young program manager, pushed forward with the project even as Bob flopped; like Karen Fries and Barry Linnett, Hobson trusted the research of Nass and Reeves on creating social interfaces. Unlike the leaders of Bob, the Office team didn’t face the unenviable task of building an alternate realm for computer novices.

Still, “there was a lot of skepticism,” remembers Ben Waldman, the head of development for Office 97. During meetings, Bill Gates would delight in mocking the idea of a character constantly interrupting in Word and other Office products. His squawking derision wasn’t unusual during pitches—even about products he liked. But his constant use of “clown” to describe the assistant would live in infamy in the halls of the tech company. Especially after Waldman embedded “tfc” in the source code for the assistant—“the friendly character” to anyone who asked, but “the fucking clown” to everyone in the know.

Hobson, the program manager, traveled around the world to test different characters for the new Office release. After all those focus groups, a robot, cat, dog, globe, and several other assistants would emerge as the original roster of assistants in Office 97. But many users never knew they had options; Clippy was the default.

The paperclip didn’t get blasted off the bat—some reviewers even acknowledged its helpfulness. But its passive aggressive queries about saving documents and writing letters got old quickly for frequent users. “These toon-zombies are as insistent on popping up again as Wile E. Coyote,” Stephen Manes wrote for The New York Times in 1997.

The assistant’s intrusions paralleled what former Windows president Steven Sinofsky calls the company’s “interrupt culture” in his Substack memoir, Hardcore Software. Friendly drop-ins to talk through projects were common on campus. But polite as they were, these impromptu messages didn’t translate well to the screen. Clippy’s interruptions confirmed our early suspicions about the people who made and managed computers—socially awkward dudes who thought they knew better than us—and, one popup window at a time, our powerlessness to stop them.

Kevan Atteberry, Mac devotee, never experienced this irritation firsthand. But the illustrator quickly realized the character was not well-received.

Eventually he stopped contracting with Microsoft to tend to his young family and neglected personal design business. When he searched for new work, he opted not to put Clippy on his resume.

Microsoft just couldn’t let Clippy go. Facing sharp criticism and hawking more useful features, the company turned the assistant off by default in Windows XP. But oddly, Microsoft decided to keep its punchline in the news cycle during the marketing campaign for XP. Team members flew to San Francisco for a press conference to announce Clippy’s retirement. Some poor soul donned a Clippy costume on the streetcar.

The company tapped comedian Gilbert Gottfried to voice the paperclip in a series of animated shorts announcing the feature’s “retirement.” His shrill pleas for a job were almost as weird as a virtual game on Microsoft’s site. Players could exact revenge on the paperclip by firing rubber bands, staples, and other office supplies at the defenseless assistant.

The XP rollout embraced the hate. With the internet in its infancy, viral Clippy screeds were certainly on the company’s radar. But over time, the web unearthed a different kind of obsession with the paperclip.

Kevan Atteberry started receiving a trickle of fan mail in his inbox. One supporter in Colombia created his own Clippy cartoons and fanfic. Others just wanted him to know how funny and helpful the assistant was. Many sent him links to pop culture references—a Clippy grave, a Darth Vader meme, the late night appearances, that awful erotica. He still has them bookmarked.

The support showed up in real life, too. At client dinners, on trains. The artist hadn’t quite fathomed the ubiquity of his paperclip until all those memes and encounters. Some even tried to claim credit for the original design. Atteberry would send files to Microsoft’s legal department to prove he was the sole designer. “It’ll probably be mentioned when I die, the creator of Clippy or whatever,” he realized.

He added the illustration back into his portfolio and started dropping it in casual conversation. Even if people hated the paperclip, they felt attached to it. Microsoft itself didn’t completely remove the feature until Office 2007.

About a decade ago, shortly after the death of his wife from an illness, Atteberry went to Burning Man. Festivalgoers dole out “playa names,” or alternate identities, in the annual haze of the desert. They didn’t have to think too hard about Atteberry’s. He spent the trip answering to “Clippy.”

On July 14, 2021, Microsoft teased an overhaul to its graphics with some shameless Twitter marketing. “If this gets 20k likes,” the company tweeted, “we’ll replace the paperclip emoji in Microsoft 365 with Clippy.”

It received close to 170,000. For some, maybe it was just a “popcorn” situation. Or a way to make a tech titan relive a failure. “Yeah, you made billions,” says Byron Reeves, who’s still at Stanford today. “But you also made this dumb little character.” Others, however, expressed genuine excitement.

Microsoft certainly hasn’t run from the revival. The emoji, video background, and a sticker pack with Clippy in Teams all remain extant from last year. More recently, the company has added the paperclip to Halo Infinite. Gamers can affix “Clipster” to guns and nameplates.

The company says it’s not trying to make Clippy a main character again. “Clippy is

living its best life,” a spokesperson relayed. “All the perks of retirement, while still being able to pop up and delight users in unexpected places.”

These cameos can be easy to miss. Many sources for this story weren’t even aware of them. Some thought Clippy’s reemergence was a simple case of capitalizing on ’90s nostalgia. It was Clippy the cultural icon, after all, that had survived, not Clippy the task wizard who constantly interrupted.

Others stressed that the idea of an assistant was just ahead of the technology. Today the artificial intelligence of Cortana, Siri, Alexa, and Google Assistant can constantly get smarter. Clippy was only as bright as the next edition of Office.

For Karen Fries, who left Microsoft in 2007 to found a clean energy nonprofit and retreat to a private life on Bainbridge Island, Clippy’s comeback proves Reeves and the late Clifford Nass were right all along. “We’re not able to fully disengage from the social aspects of using a machine,” she says.

Still, Fries notes, you don’t normally see this level of emotional attachment to tech. A group of researchers from Microsoft, MIT, and elsewhere recently looked into it. They analyzed all those Clippy memes—340 unique ones. They found that what Clippy was missing—the interpersonal skills to adapt, the “natural” part of Reeves and Nass’s theory in The Media Equation—is also what makes him funny today. “This constant failure makes Clippy less effective but more interesting and, at least in retrospect, endearing than contemporary adaptive digital assistance,” the study concluded. In other words, it reminds us of a time when assistants couldn’t target us with ads or mimic a dead loved one’s voice. When tech, even in the form of a clueless office supply, seemed a little more human.