Last year, the most extensive public exhibition about police violence and institutional racism went on display in Britain. War Inna Babylon, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, investigated the scope of policing and contextualised the experience of Black Britons who have fought for justice. Its primary focus was the brutal and hostile policing that our community faces and the many lives that have been tragically stolen by the police. Exhibition organisers, including myself, compiled a list of 136 names of Black people killed in police custody or after contact with the police since 1990, alongside documentation of numerous others since the death of David Oluwale in 1969.

This week we have been forced to come together again – not to celebrate any progress in race relations between the police and our community, but to mourn for another young Black man who was tragically and inexplicably killed by police. Chris Kaba, who was fatally shot by the police on 5 September, is one of 35 Black men who have been killed either while in police custody or after contact with the police since Mark Duggan’s death in 2011. Many of these men died after the “use of force”.

Britain’s Black communities have long been aware of the racist, oppressive and fatal policing across this country. Last month, we witnessed the horrific sight of Oladeji Omishore, who fell into the River Thames after being Tasered by police. The month before, a public inquiry returned a verdict of lawful killing in the case of Jermaine Baker – who was shot while in a car, unarmed, while putting his hands up. The killing of Chris Kaba did not happen in isolation. After an inquiry into the shooting of Azelle Rodney in 2005, who was also seated in a car at the time of his death, the independent police watchdog recommended the Met police review its use of the controversial “hard stop” tactic, which involves armed officers deliberately intercepting a vehicle to confront suspects. The independent body warned at the time that this tactic was a “high-risk option”.

In 2014, after the inquest into Mark Duggan’s death, the new Met commissioner, Mark Rowley (who was then assistant commissioner) was forced to publicly admit that the force had failed to review the tactic before Duggan was gunned down during a hard stop in August 2011. Police also forcibly stopped the vehicle that Chris Kaba was driving on the day he was killed. This is exactly why his family called for the protest march that took place in central London on Saturday. His family are seeking answers that will help them to understand exactly how officers from a specialist firearms unit shot and killed their unarmed son without him even having the chance to identify himself, using methods that have been identified as dangerous.

Saturday’s march wasn’t just a memorial for Chris Kaba. It was about sending a strong message to Scotland Yard: enough is enough. We marched to demand that the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC), the Equality and Human Rights Commission and the mayor’s office for police and crime do their jobs properly, and root our the violent institutional racism that has long persisted in the Met. Chris Kaba’s family and our wider community have welcomed the announcement that the officer who shot him will be subject to a homicide investigation. But given past failings, we feel unable to put much faith in the IOPC.

As a result of evidence presented at recent inquests, the police watchdog has recently been forced to reopen a number of its own investigations, including those into the deaths of Kevin Clarke, who was restrained by police shortly before he died, and Darren Cumberbatch, who died after being Tasered by officers. Previously, the IOPC had sought to exonerate officers involved.

We view the killing of Chris Kaba as an extension of the brutal overpolicing that Black communities faced during lockdown. It is this same type of policing that allowed innocent children such as Child Q, and 649 other children over a two-year period, to be forcibly and traumatically strip-searched by Met officers. It is the same kind of policing that led to the supreme court ruling stating that politicians, courts and police had taken a “wrong turn” in the use of the “joint enterprise” doctrine in 2016 and it had been “misinterpreted”. It is the same kind of policing that led to the creation of the racist “gangs matrix” database which the information commissioner’s office found to have breached all data, privacy and equality legislation, and risked “causing damage and distress to many people – mainly young, Black men”.

On Saturday, we marched with the family and friends of Chris Kaba and for all those who have died at the hands of the police, who deserve more support in these vulnerable moments. We marched because our experiences of policing and the criminal justice system remind us “there is no justice, there is just us”. People from all parts of the capital, both Black and white, came to call for an end to what we see as the extrajudicial killings of young Black men on the streets of London, and elsewhere, by those whose job it is to protect them.

As Temi Mwale, one of the activists involved in organising Saturday’s march, told me: “We marched and we chanted ‘touch one, touch all’ and this sums up why the protest was so important. The killing of Chris Kaba has deeply hurt us all. There exists no language that is able to fully articulate the depth of pain we feel.” Public awareness of institutional racism within the criminal justice system is growing, but little has been done to address the root causes of this pernicious form of discrimination. As a result, many people in our community have little faith, trust and confidence in the state or official regulators to hold itself and its agents to account when things go tragically wrong.

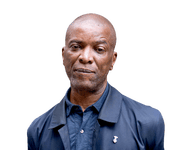

Stafford Scott is the director of Tottenham Rights and a guest professor at Forensic Architecture, Goldsmiths, University of London