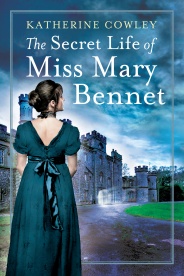

Start reading this book:

Share This Excerpt

Miss Mary Bennet could do nothing to stop her life from shattering to pieces, so she played the pianoforte.

Her cousin, Mr. Collins, had arrived to take possession of Longbourn before her father, Mr. Bennet, was even in the grave. As Mr. Collins and the men he had hired swept through the house, removing items he had sold, Mary attempted to drown out the commotion by playing faster and faster, louder and louder, until her younger sister, Kitty, exclaimed, “Can you please stop, Mary!”

Mary pulled her fingers off the keys and sniffed.

Their eldest sister, Jane—known as Mrs. Bingley since her marriage not quite a year before—cleared her throat. “What I think Kitty means to say is it might be more appropriate to play that funeral march with a little more solemnity.”

Mary tried not to take offense. It was she, of all her sisters, who had applied herself most to the pianoforte over the years. Should she not be able to choose the manner in which she played?

A sticky summer scent blew in through the open window, and the breeze disturbed Mary’s music. She carefully rearranged the pages.

Kitty, Jane, and Elizabeth were seated at a nearby table assisting with the funeral preparations. They answered letters of condolence and sorted the black gloves for the funeral guests. In a few minutes they would organize the mourning rings. Mary had assisted them for a while, but she was more inclined to pass the time on the pianoforte. However, if they would not appreciate her playing—

“Oh, here is a letter from Lydia,” said Elizabeth.

Lydia was their youngest sister and had been the first to marry, to a Mr. Wickham. Elizabeth’s husband, Mr. Darcy, had purchased him a new commission, and his regiment was currently training so they could travel to the continent and fight against Napoleon Bonaparte.

Mary did not leave the pianoforte, but she did lean forward to better hear the contents of the letter.

Dearest Mother and Sisters,

I am devastated by the death of Father, and I have not stopped shedding tears since I heard the news. While I would love to return to Longbourn, my dear Wickham must remain here, and I find myself unable to part from him for even a few days. Surely you understand what it is to be newly married and in love.

I have used the money that you sent to purchase clothes of mourning. Have you seen the advertisements? In London some women are wearing burgundy for mourning instead of black. I went to the dressmaker and chose out a fine fabric. I intend to be the envy of all the mourners.

I will be thinking of each of you with fondness. Know that you and Father are in my heart.

With love and tears,

Lydia

The four sisters sat in shocked silence.

After a moment of reflection, Mary felt prepared to speak. “A duty to one’s spouse is paramount, but in this case, a duty to one’s parents should take precedence. To spend the money meant for travelling costs on expensive mourning clothing instead—that speaks of focusing on matters of little worth. Hannah More wrote, ‘A life devoted to trifles not only takes away the inclination, but the capacity for higher pursuits.’”

“Thank you, Mary,” said Jane.

“How could she write such a letter at a time like this, with such disregard for our father?” said Elizabeth. Elizabeth was often the most rational of Mary’s sisters, which was an admirable trait, and she generally managed to express her sentiments in a concise yet compelling manner, a skill which Mary wished she could imitate.

“Even if I were married to a man like Wickham,” said Kitty, “I would come for a funeral.”

Jane reached across the table and took the letter. She would probably say something altogether too kind, and more forgiving than Lydia deserved.

“Oh, surely she is prevented for some reason from coming and is using this excuse as a mask for her emotions. See this line, ‘I have not stopped shedding tears since I heard the news.’ Do you not hear the real sadness there?”

Mary did not sense any sadness on Lydia’s part. Of course, she had never understood her youngest sister. She tried to withhold judgment, for various sermons said it was not man’s role to judge, yet she often found herself condemning Lydia’s follies. Jane and Elizabeth had come when their father had taken ill; all his daughters had been there with him in the moment he took his last breath. All except Lydia. And now she chose not to attend his funeral.

A man entered the room without the courtesy of a knock or warning, and they silenced and turned back to their work. It was best not to discuss overly personal matters in front of servants, and this seemed especially true for the men hired by Mr. Collins.

Due to the entailment, which was unalterable, as each of the daughters tried to explain to Mrs. Bennet time and time again, the estate and most of its possessions went not to any of Mr. Bennet’s daughters, but rather to his closest male relative, Mr. Collins.

Mr. Collins had been serving as a clergyman, but upon Mr. Bennet’s death a week before, had decided to renounce the living and devote himself to the running of Longbourn. After his arrival, his first task was to follow the advice of his esteemed patroness, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, and to immediately, without any delay, make the estate match his personal expectations of taste and comfort. Mr. and Mrs. Collins intended to use some of the existing furniture at Longbourn, but they also planned to bring some of their own pieces, and so Mr. Collins had arranged to sell the excess. Mary wondered how a mismatched collection of furniture would serve them, but it was his furniture, and he could do with it as he liked.

He had stated that Mrs. Bennet could remain at Longbourn until she chose a permanent place. In the meantime, she could even maintain possession of her bedroom, which he admitted was the best in the house and would be within his rights to occupy (though of course his sense of duty to Mrs. Bennet would not allow him to take it from her). All of Mr. Collins’s actions and words seemed, on the surface, very rational to Mary, yet somehow his mannerisms left her feeling that he should be doing more to accommodate their family.

Despite Mr. Collins’s insistence that his goal was to make the situation agreeable to everyone, Mrs. Bennet had declared that she would not be a guest in her own home. She had wanted to vacate the premises immediately, but Mary and Kitty had convinced her that they should not leave until several days after the funeral. Mary could not abandon her father’s body to the care of Mr. Collins; she and her sisters would watch over it. Meanwhile, Mr. Collins’s haste in selling the existing furniture did make living here during the funeral preparations more difficult. She could not even play a funeral march uninterrupted.

The hired man passed rather closely to where Jane, Kitty, and Elizabeth were seated. A loud noise, perhaps some sort of bird, came from outside; it was louder than a typical bird, and not the sort of sound one normally heard in these parts. They all turned to look, but there was nothing to be seen, so after a moment they returned to their tasks. The hired man was examining an upholstered chair. He paused and looked briefly at Mary with the sort of focused attention that disconcerted her. His eyes then turned to Kitty before returning to the chair.

“Will you be sitting with Father tonight, Mary?” asked Jane.

“Yes, I am prepared to do my duty.” She considered saying more, but she was distracted as the man lifted the chair.

As he passed her on the way out of the room, Mary could not help but notice that his clothes seemed a bit crisper than those of the other hired men, and his cravat was a slightly different shade of brown. She did not recognize his face, though it was a very normal face, with no distinguishing characteristics. He must have arrived later than the other men, or maybe he had been sitting with the wagons until now, but still, something about him unsettled her.

“Did anyone notice something strange about that servant?”

Elizabeth and Jane shook their heads, quizzical expressions on their faces.

Kitty leaned forward and said, in a conspiratorial whisper, “Did he do something untoward?”

“Of course not,” said Mary. “But I was certain Mr. Collins only brought eight men, and he was not one of them.” Not only had she sensed that he did not belong, but she felt like he had been evaluating her.

Kitty gave a brief, derisive laugh. “You counted the men he brought?”

Mary looked down at the pianoforte’s keys. Kitty had spent a lot of time mocking her lately. Mary ignored it with practiced indifference, but still it grated on her.

For the most part, she had liked it better when all four of her sisters had been at home. But of course, it was impossible for things to always stay the same. She had lost Elizabeth, Jane, and Lydia to marriage. Elizabeth lived at Pemberley, Lydia with Wickham’s regiment, and Jane and Mr. Bingley had recently given up Netherfield Hall and bought their own property near Pemberley. With her father’s death, she had only her mother and Kitty to look forward to for constant company. It still had not been decided where they would live permanently after the funeral, but once they vacated Longbourn, they would live, for a time, with Mrs. Bennet’s sister, Mrs. Philips, in Meryton. Mrs. Bennet had been bedridden since Mr. Bennet had taken ill, and they could not possibly travel farther until Mrs. Bennet’s health improved.

If only Mary were married to Mr. Collins. When Elizabeth had rejected Mr. Collins’s offer of marriage, Mary had hoped that he would propose to her. But he had not, instead wedding their friend Charlotte Lucas. Mary still looked on the incident with some regret: Mr. Collins was a religious man, full of profound statements and insights, and if she had married him, the Bennets would not be losing their home and possessions.

Mary breathed deeply, then set her fingers back onto the keys. She resumed the funeral march from where she had left off, this time playing so solemnly and slowly that no one could possibly complain. If she were of a more curious nature, perhaps she would make further inquiries after the servant, but it was a matter of little import.

“I have a mind to join the funeral procession,” said Elizabeth.

Mary paused, and Jane and Kitty looked up. What a strange idea. Of course, there was nothing that prohibited a woman from joining the funeral procession, or even the service in the church if she desired, but it defied tradition and was not part of a woman’s duty.

Mary resumed her music but paid close attention to the words of her sisters.

“Are you sure?” asked Jane. “You will be the talk of the region.”

“What does it matter to me what the people of Meryton think?”

“That is easy for you to say,” said Kitty, “with ten thousand pounds a year.”

“If I do not attend the procession, the closest blood relation to father will be Mr. Collins,” said Elizabeth. “I cannot imagine our father wanting that.”

“If you go,” said Kitty, “I will accompany you.” Every morning since their father’s death, Kitty’s cheeks had been raw and tear stained. Her outward expressions of grief seemed, for her, a necessary demonstration of her love for their father. Mary tried to keep her sentiments—which were just as strong—more contained within herself.

“What about you, Jane?” asked Elizabeth.

“I had best stay with Mama. She will need my support.” Jane’s voice sounded tired.

“And you, Mary?”

“It is not part of a daughter’s duty,” said Mary stiffly. She continued to play as she spoke, unwilling to stop, and unwilling to admit that the idea of joining the funeral procession had a certain appeal. “And besides, between the two nights I have already spent and tonight, I will have passed three nights watching his body. That is enough.”

“I think, in this situation, any of our choices are justified,” said Jane. She stood. “Now where were those mourning rings?”

The mourning rings needed to be sorted so they could be distributed as part of the funeral, one to each family member and friend who attended. It was a small token of appreciation, and something they could wear in remembrance of him.

“I put the case next to the gloves,” said Kitty. She and Elizabeth also stood. They lifted gloves, shifted letters, and examined every nearby surface.

“Did we leave them in the downstairs parlor?” asked Elizabeth.

“I know I carried them up,” insisted Kitty. “Mrs. Hill must have moved them.” The housekeeper had been in the room not long before.

But Mary suspected that Mrs. Hill would not know. She re-examined the last few minutes in her mind: the servant entering the room, the strange sound, the removal of the chair, and now the missing mourning rings. It was too much of a coincidence. Yes, they could find Mrs. Hill or Mr. Collins and assemble the hired men, but that would take time. And why require someone else to solve a problem when you could solve it yourself?

Without a word to her sisters, Mary stood and exited the room. The men would be taking the unneeded furniture out the back of the house and loading it into wagons, and so she headed that direction, in a manner that was a bit faster than was normally appropriate for young ladies (though she took care not to run). She rushed down a staircase and out the door. Her heart pounded and her lungs felt short of air.

The chair was strapped to the back of the first wagon. The wagon’s wheels began to turn.

Mary stepped onto the gravel. She hesitated, for it was never ladylike to raise one’s voice. But this was an urgent matter. “Stop! Wait!” she cried, waving her arms.

The wagon stopped, and one of Mr. Collins’s men stepped down from it. He was one of the original eight. “What do you need, miss?”

“I need to examine that chair.”

The man removed the ropes and lifted down the chair. She ran her hands over the back and sides and noted that the cushion was slightly dislodged. Beneath it she found the black velvet case. She undid the latch, opened it, and saw that it still held the rings.

By now her sisters had followed her outside. “I found it,” she called to them, holding up the case.

Mr. Collins exited the house. “What is all this commotion?”

“Someone tried to steal the mourning rings,” said Elizabeth.

“Yes,” said Kitty. “It was one of the servants. He placed them in that chair.”

Mr. Collins puffed up his chest. His hands closed tightly and then opened again, as if he was trying not to clench them. “How dare you accuse me of stealing the rings? I, who out of generosity and Christian benevolence, have allowed you to remain at Longbourn when I would have been justified in casting you out.”

“We are not accusing you in any manner,” said Jane, her voice a little strained. She worked so hard to help everyone feel better when she herself was in mourning.

“You accused one of the men I hired.” His eyes fell on Elizabeth.

Before Elizabeth could reply with something scathing, Mary interrupted. “It was not, in fact, one of the men you hired. You brought eight men, and we saw them at the start. This man, while he tried to imitate their dress, did not quite match the others, and was an impostor.”

Elizabeth and Jane spent several minutes reassuring Mr. Collins that he was at no fault, that he had been taken advantage of by the criminal, and that they placed no blame on him whatsoever. Finally, once he was properly appeased, they assembled all of Mr. Collins’s men and the household servants outside, underneath the warm, languid sun. Mary was the only one who was able to give a decent description of the man. But besides the four sisters, not a single person had seen the man who had moved the chair, and no one knew his identity.

“This chair is not even one that I have sold,” declared Mr. Collins. “Return it to the house at once.”

Eventually everyone was back in their places—Elizabeth, Kitty, and Jane carefully sorting and labeling the mourning rings, choosing which would go to which families, since their father had given only minimal details in his will. Mary tried to help them, but despite having solved the mystery, her heart continued to pound, and she could not focus on the rings. She returned to the funeral march on the pianoforte.

“How did you infer what happened?” asked Kitty with wonder.

“It seemed to be the only logical conclusion,” Mary replied. “First there was the servant I did not recognize, then a noise from outside which distracted us, and then he removed the chair, and not long after we noticed the mourning rings gone.” She felt warmth inside, a joy at being of assistance. Yet the fact that they had not found the thief troubled her. Where was he now? And what crime would he commit next?

After a few minutes, Mr. Collins entered the room with four of the men. Mary was surprised when Mr. Collins spoke to her rather than her sisters.

“Miss Bennet, I find it necessary to address you at this time.”

She stopped playing and rested her hands on her lap. “You have my attention, Mr. Collins.”

“It is quite unfortunate, especially in light of you clearing up the matter of the mourning rings, but I need to remove the pianoforte.”

Mary stared at him, disbelief on her face. “But I…but I need it.”

“However, I do not need it. The esteemed Lady Catherine de Bourgh, who has always been so generous to our family, recently gifted us with our own instrument. It is a much finer pianoforte and should arrive within a few weeks.”

Mary did not move from the bench. Her hands instinctively reached out to the pianoforte, and she gripped the instrument as if holding on for dear life.

“I have found someone willing to pay forty pounds for this pianoforte as it is rather old and does not have the best sound. But, as you are family, if you are willing to pay thirty-five pounds, you can keep it and take it with you.”

Thirty-five pounds. The amount was impossible. At the moment, she had only a few pounds of her own. Mrs. Bennet’s remaining fortune was five thousand pounds, which, invested in the four per cents, gave them only two hundred pounds a year to live off of, a drastic decrease from the two thousand pounds a year provided by Mr. Bennet. When her mother died, Mary would only inherit one thousand pounds, which would give her only forty pounds a year with which to maintain herself. She could not possibly purchase the pianoforte, no matter how dear.

“Let go of the instrument, Miss Mary,” directed Mr. Collins.

Her fingers tightened further. She could not let go of this pianoforte that she played for hours every day—this instrument that made her life tolerable even in the hardest of times.

“But Mr. Collins,” said Jane, “surely the pianoforte could wait two days to be taken.”

“Lady Catherine de Bourgh told me that it was best to arrange all of my affairs as quickly as possible when I arrived, and I intend to do so.”

“Can you not see that Mary is distraught?” said Elizabeth. “And you claim to be a gentleman.”

“I suppose Miss Bennet’s unseemly behaviour may be excused due to the loss of Mr. Bennet. If it were possible, I would delay the removal of the pianoforte, but I have only hired the servants for today.”

Mary pressed her lips firmly together, determined not to succumb to an outward display of emotion. The pianoforte was the only thing she had found in the past week to keep her sorrow in check. Yet she would find a way to move forward without it, even as Mr. Collins cast her out of Longbourn, adrift and without anchor, into the world.

“I will do no more to embarrass you, cousin,” said Mary. She stood and collected the music sitting on the pianoforte, then sorted it into two piles, one large, one small.

She handed Mr. Collins the larger pile. “This music belongs to the estate and is now yours.” She picked up the smaller pile. “But this music is mine, and I will bring it with me.”

Ignoring her sisters’ attempts to comfort her, Mary turned and marched out of the room with whatever semblance of dignity she had left.

End of Excerpt