The call came in a little after 9 p.m. on September 5: a medevac was needed for two badly injured wildland firefighters in Northern California’s Trinity Alps, in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest.

It wasn’t unexpected. Fighting fires in the backcountry was a dangerous job, and the 2019 fire season was well underway. Lightning had already ignited 124 blazes across the region in September, including 18 in Shasta-Trinity alone.

What was surprising was who picked up the call: the U.S. Coast Guard Sector Humboldt Bay in McKinleyville, about 58 miles west of the firefighters.

The helicopter rescue team on duty—aircraft commander Derek Schramel, 36; copilot Adam Ownbey, 32; rescue swimmer Graham McGinnis, 34; and flight mechanic Tyler Cook, 23—were just settling in for the night when they were summoned to the command center.

They went over what little information they had. Two wildland firefighters, part of a 20-person crew employed by a private company under contract to the U.S. Forest Service, had been hit by a rolling boulder: one in the head and neck, who had been knocked unconscious for approximately 30 seconds, and the other in the leg, whose femur was shattered.

This article was featured in Alta Journal's free Weekend Read newsletter.

SUBSCRIBE

The pair were stuck on a steep slope at about 5,000 feet, close to the fire line and miles from the nearest major road. Carrying them out would be next to impossible—the ground was covered with rocks and downed trees—and could put everyone’s lives at risk. The crew’s leader—whom the Coast Guard would call the incident commander throughout this ordeal—said on the radio that both men were in bad shape. He was worried that the one with the broken leg might not survive the night.

Two agencies, including the California Highway Patrol, were contacted to perform a search and rescue mission; the CHP was deterred by the risk involved. The incident commander was desperate.

Coast Guard helicopter rescue teams train endlessly to do things like pull sailors off floundering ships in stormy seas. In fact, Schramel and the others had spent the afternoon practicing hoists off a 47-foot Coast Guard motor lifeboat. Teams like theirs are encouraged to think outside the box and improvise in new situations.

But lifting severely injured firefighters off a burning mountain? “That was vastly outside our realm of experience,” Schramel says. Cook was the newest flight mechanic in the unit, and neither he nor Ownbey had ever flown a search and rescue mission before.

Their twin-engine Dolphin MH-65 helicopter was sleek and agile. But the red-and-white craft had limited power and fuel reserves, its performance started to suffer above about 3,000 feet, and fire-heated air is thinner and offers less lift. In any case, landing in a forest of 200-foot trees was out of the question. The firefighting crew had cut down enough trees to make a small clearing, which meant the rescue team would have to perform a cable hoist from a high hover, at night, a challenging operation under the best of conditions.

McGinnis had been with the unit for only a few months, but his EMT training compelled him to speak up. A broken femur can be life-threatening, he said. If a femoral artery is cut, you can bleed out internally and never see a drop of blood.

That very thing had happened in the same forest in 2008. A firefighter with Olympic National Park, his femur shattered by a falling tree, had bled to death in the back of a Coast Guard helicopter after waiting for hours to be rescued. That wasn’t the only disaster that season: two weeks later, an overloaded helicopter crashed during takeoff from a remote helispot, killing seven firefighters and two pilots.

Coast Guard teams evaluate every potential mission in terms of risk versus gain. Everyone has to be in agreement, and anyone can decide to turn around at any time. McGinnis and the others decided that the severity of the injuries and the fact that they were likely the only remaining medevac option within range tilted the equation enough to at least try. They would fly to the scene and see whether a rescue was even possible.

They started gearing up and prepping the Dolphin for flight. At 11 p.m., with Ownbey at the controls, they took off from the fog-covered airfield and flew east into the alps.

During the half-hour flight, the team went over checklists and did their best to game-plan potential scenarios. A quarter moon was setting, leaving the mountains in darkness almost too deep for their night vision goggles. They then cleared a ridge, and a huge glow lit the horizon.

“That was a gut check for all of us—what exactly are we getting ourselves into?” Schramel said.

A half dozen firefighters were stuck in a north-south canyon about three miles wide and surrounded by sheer ridgelines on three sides, like a bowl. The top half of the east ridge was on fire. Smoke filled the canyon, rising into an anvil-like thunderhead.

Schramel took the controls from Ownbey and started circling. They spotted a trail of headlamps on the east ridge about half a mile below the fire line and radioed the incident commander to say they were headed his way.

“No, that’s not us,” he said. “That’s our relief team coming up. You need to look higher up toward the fire.”

It took one more pass to find the faint glint of more headlamps about 20 yards from the fire line.

“You could feel it in the aircraft,” McGinnis says. “Everybody was like—whoa.”

Schramel started working to get into a hover over the clearing the firefighters had cut. Every workable approach route seemed to carry them over the flames. The air, already thinned by the heat and elevation, churned with updrafts of up to 100 miles per hour, forcing him to adjust power to keep a steady altitude.

Whenever they reached the clearing, the updrafts would abruptly stop, and the Dolphin would start to fall toward the trees. Each time, Schramel had to peel away down the canyon just to stay in the air.

He had no depth perception through his night vision goggles, and whenever he looked near the fire, the flames’ light turned his field of vision into blinding static. With no flat horizon for reference, he fought the vertigo that can make helicopter pilots misjudge their orientation and tilt in the wrong direction.

Schramel had 11 years of flying experience and was an instructor at the Coast Guard’s Advanced Helicopter Rescue School. But this was the toughest flying he had ever done.

“There’s no words to describe how hard it was,” he says. “My sole preoccupation was trying not to kill everybody.”

He kept trying. In the copilot seat, Ownbey served as a second pair of eyes, monitoring the instruments and watching the fuel level creep closer to “bingo,” the cutoff point where there was just enough left to fly back. McGinnis could hear the doubt in their voices as they tried to maneuver into position again and again.

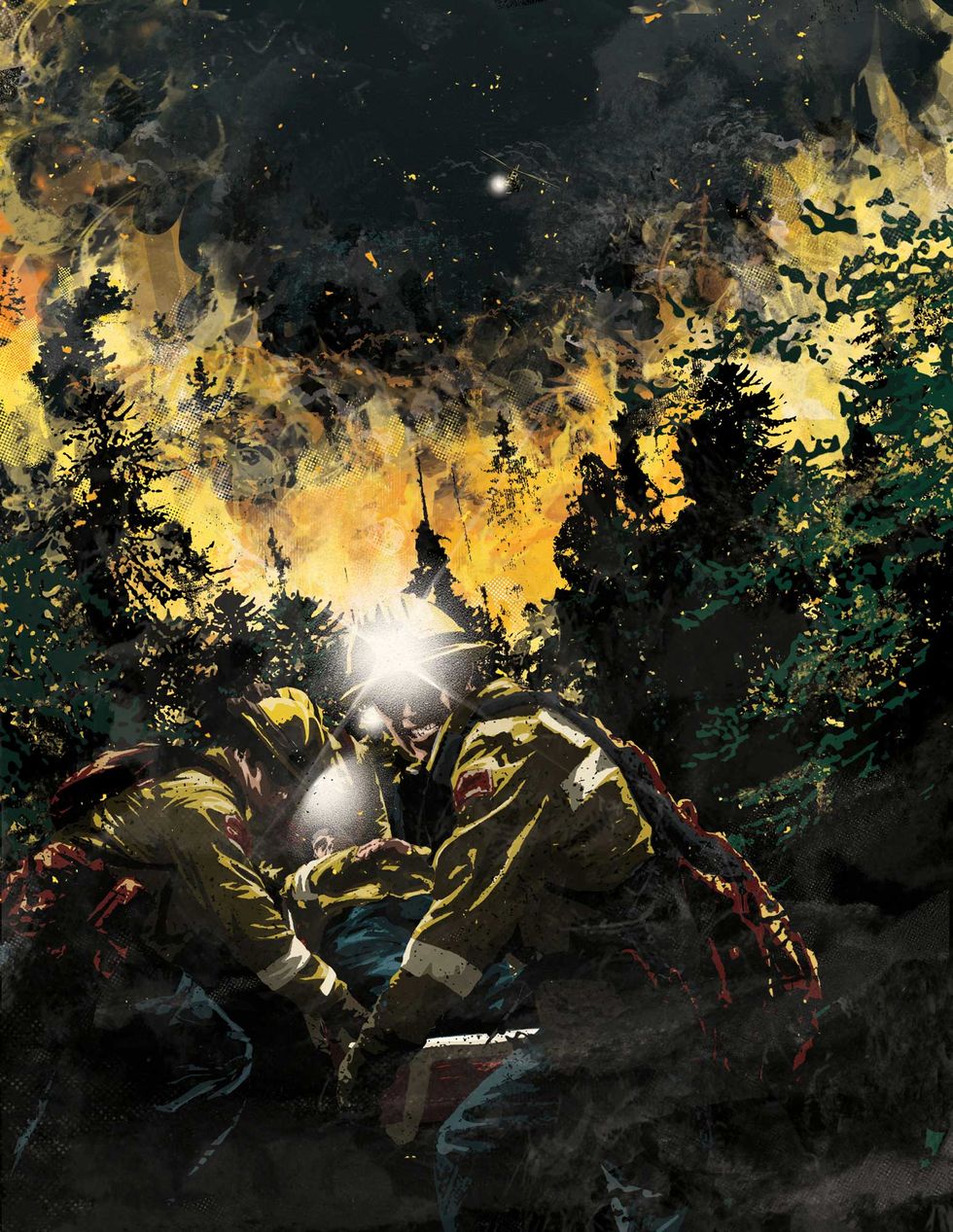

After about 10 tries, Schramel found an approach that avoided the flames: he skimmed a high ridge at treetop level and made a fast descent toward the clearing. It was almost midnight when he settled into a hover. The mountainside was so steep that redwoods rose above them on two sides.

McGinnis sprang into action. He hooked his harness to the end of the hoist cable and looked out the open door on the Dolphin’s right side. The only light came from the fire and the helicopter’s spotlights knifing through the smoky air.

This article appears in the Fall 2022 issue of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

He looked down at the tiny clearing lit by flaming trees. The Dolphin was at least 200 feet above it, and the cable was only 240 feet long. If Schramel lost power or veered just slightly too far in any direction, McGinnis could be dragged through the trees, or the cable could snap, or both. He sized up the situation and told Schramel that if things got out of control once he was on the ground, the aircraft commander should leave him behind, even overnight. Absolutely not, Schramel replied.

McGinnis had made it through the Coast Guard’s grueling training program, his branch’s equivalent of the Navy’s SEAL training. During Hurricane Harvey in 2017, he had waded through flooded Houston neighborhoods, searching for people trapped on roofs, and watched as a hoist cable was sheared by a power line. Still, the view over the burning ridge left him momentarily speechless.

“What the fuck am I doing?” he said.

He knew that flight mechanics like Cook had hundreds of hours of experience in hoisting swimmers to safety. Still, as he prepared to step out the door, he gestured and yelled at Cook to watch out for the “candy cane,” the red-and-white warning stripes that marked the last 10 feet of cable.

“I kind of gave him the googly eyes,” McGinnis says. “ ‘Hey, man, just watch.’ ”

It took so long to get to the ground that the roar of the rotors eventually began to fade overhead. Then McGinnis started to spin. “I just remember seeing black, fire, tree, black, fire, tree, over and over,” he says.

Cook watched the glow of the flashlight on McGinnis’s helmet grow dimmer. Along with manning the winch, his job was to give Schramel directions to keep them over the clearing: “Tree just off your nose. You’re drifting right. Hold position.”

McGinnis was still at least 25 feet off the ground when the candy cane appeared. Cook carefully guided Schramel to bring the helicopter to the side until McGinnis could grab a tree, unhook from the cable, and shimmy down awkwardly. It wasn’t pretty, but it got him to the ground.

He scrambled uphill over a mass of felled trees to reach the firefighters. Half a dozen men in yellow shirts and hard hats stood backlit by fire and covered in dust. The two injured firefighters were already strapped onto backboards and covered with Mylar blankets. Within seconds, the rotor wash whipped the blankets away, and McGinnis could see one man’s right foot pointed almost backward.

He radioed up for Cook to lower the litter. But on the way down, it started to pendulum in bigger and bigger arcs. Cook had no choice but to bring the litter back up to attach a trail line to it. Before he could do this, they were at bingo. They had only enough fuel left to bring McGinnis up.

McGinnis told the incident commander they had to go. They would head to Redding, about 50 miles southeast, to refuel and reassess the situation. He knew there was a chance they wouldn’t be allowed to come back, if the higher-ups decided the mission was too risky. “I didn’t want to give any promises,” he says. “He was obviously disappointed.”

Cook had to guide the helicopter even lower so McGinnis could hook back onto the cable. The ride up was just as frightening as the descent. “I had to consciously force myself to stop white-knuckling the hoist hook so I didn’t unintentionally unlock it,” he says.

The atmosphere in the cabin was grim on the way to Redding. “Everyone was palpably dismayed—the doubt was definitely creeping in hard,” McGinnis says.

They landed at the Redding airport at about 2 a.m. and started talking as the helicopter was being refueled.

“I saw the patients, and they’re in bad shape,” McGinnis told his teammates. “And they’re not going to be able to hike these guys out on backboards—it’s just too rugged.”

Remember how hard it was just to find the right approach angle, he added. Any other helicopter team that went out would be starting over from scratch. They weren’t just the best hope of rescue—they were very likely the only one.

The team started running the numbers on fuel, weight, distance, and time. They did this on every mission, but the margins here were especially slim. Every extra pound of fuel, gear, or people limited their flight time and affected the aircraft’s performance. It was a complex calculation with lives on the line.

McGinnis had two ideas that might give them more of a safety margin. Instead of lowering him and the rescue litter separately, they could send them both down at once; then they could bring him and a patient back up at the same time. This would cut hoist time in half and could mean the difference between rescuing one or both men.

The maneuver wasn’t part of standard Coast Guard training, and none of them had ever tried it before. But other agencies and private companies apparently did it, and it didn’t seem that complicated.

And if they fieldstripped the aircraft of everything they didn’t absolutely need, as another team had done during Hurricane Harvey, they could eke out more time in the air and leave more room for the patients.

They checked in with their commander, who approved the plan. They would retrieve both patients, if possible, and bring them to a small airfield in Weaverville, only a five-minute flight from the rescue scene. There, they would transfer the patients to a private emergency air medical service called REACH. That airfield didn’t have refueling services, so there would be no return trip for McGinnis and his companions.

The team started dumping out everything that wasn’t nailed down: rafts, searchlights, extra seats, anything related to water rescues. When they were done, over 200 pounds of gear lay piled on the floor of the hangar.

By 3 a.m., the Dolphin was aloft and en route. When they updated the incident commander on their position, he said that his crew had tried to carry the femur patient down the mountain. In an hour, they had gone only 40 feet.

The Coast Guard team arrived to find that the fire had crawled downhill, closer to the clearing, which was now surrounded by burning trees on three sides. There was only one approach route that wasn’t on fire: flying straight toward the mountainside. That meant that if they lost power, a crash was almost inevitable.

Schramel could barely see through the smoke and flying embers. Aiming one of the landing lights horizontally at the trees gave him a makeshift reference point, and somehow he managed to get into a hover again.

McGinnis struggled to connect himself and the litter to the hoist hook and wrestle the whole setup into position. The rotors sucked smoke into the cabin like a black tornado as he hooked up and Cook helped him shuffle toward the open door.

McGinnis could feel the heat of the fire on the way down. The air was full of dust and ash, and flames were climbing the trees right under the tail of the helicopter. (“That got my attention,” he says.) He landed and lugged the litter up the hill to where the fire crew were waiting, now only a few dozen feet from the fire line.

He jammed the litter into the hillside below the first patient, wedging his knees underneath to keep it horizontal. McGinnis estimated that the man weighed about 280 pounds. He screamed as his crewmates lifted him onto the litter. “I could see his thigh jiggling like jello,” McGinnis says.

In just minutes, McGinnis and the patient were ready for Cook to begin lifting them to the helicopter. Their combined weight made the Dolphin dip to the right, but Schramel reacted quickly and steadied the aircraft.

As McGinnis clambered aboard, Cook helped maneuver the litter inside. The men tried to lift the patient, still attached to the backboard, out of the litter and onto a low shelf inside the low-ceilinged, cramped space. McGinnis squatted and lifted as Cook pushed from below. But no matter how hard they strained, the backboard just wouldn’t budge.

“At this point, my brain is going, ‘You’re running out of time, you’re running out of time,’ ” McGinnis says. Every extra second they spent hovering was burning fuel and flight time.

McGinnis gave one huge heave and howled as pain from a pulled muscle shot through his back. The backboard popped free—a buckle had been caught on the litter—and he and Cook managed to heave the patient onto the shelf. They immediately started readying themselves to fetch the next man. There was no way they could leave him behind.

Beginning his descent, McGinnis could see that just a few minutes of hovering had fanned the flames even higher. Blowing ash and dust were working through the balaclava over his mouth, and he could feel grit on his teeth. But he was humming on adrenaline, and now he knew the new hoist method worked.

The second patient was shirtless, with a cervical collar as well as bandages around his head and one shoulder. His fellow firefighters were clearly relieved that their crewmates were likely going to be safe. Just before the cable went taut, one of them, blackened from head to toe in dirt and ash, leaned over McGinnis and said thanks.

The final hoist seemed to take forever. McGinnis looked down at the red glow of the fire just feet from where he had been standing. He could feel himself grinning in disbelief. “I can’t believe we just pulled this off,” he thought.

With the litter on the floor, there was just enough room to close the cabin door. Schramel had to push the engines to maximum power to make up for all the weight. The altitude slowly ticked up foot by foot. “Thank god that was the last hoist,” he says. “There was no way we could have hovered another 30 seconds.”

When they were clear of the burning treetops, he passed the controls to Ownbey and took a deep breath.

“I swear on my life, I looked forward and watched his shoulders drop from up near his ears,” McGinnis says.

Ownbey landed at the small, unlit airfield in the forest outside Weaverville just shy of 4 a.m. Before he was even out of his seat, the patients were unloaded and whisked to a pair of waiting REACH helicopters.

The night was suddenly quiet. The team members looked at one another, exhaustion crashing in, wondering what had just happened. “It was an adrenaline dump, for sure,” Ownbey says. None of them had ever been through anything remotely like the past six hours.

Their most immediate concern was where they were going to sleep. They were tired enough to consider spending the night in the Dolphin. Luckily for them, they were able to catch a ride with a California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection crew to a fire station a few minutes away. “We ended up straggling along with them like lost puppies,” Schramel says. A couch and a couple of recliners had never looked so inviting.

“My brain is going, ‘You’re running out of time, you’re running McGinnis couldn’t sleep because of the pain in his back. He finally gave up and went outside. The rising sun was just starting to burn off the early-morning chill. He found a trail around the building and followed it, trying to stretch out the muscles in his back, going over and over in his head what had just happened and how everything, incredibly, had seemed to fall into place.

The two patients survived, and the rest of the fire crew made it out safely on foot. The morning after the rescue, a spokesperson for the firefighting company, GFP Enterprises, told local news site Redheaded Blackbelt that both men were in “really good spirits [and] one wanted to go back to work today.”

Schramel later reached out to the company to check on the patients, but nobody ever called him back. “It’s a bummer, but that’s the nature of our work sometimes,” he says. “You rarely get to talk to that person after you drop them off.” (GFP Enterprises didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

In the months to come, McGinnis and Schramel would be awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the U.S. military’s highest aviation award for heroism in flight. Ownbey and Cook would receive Air Medals, recognition for their own heroism. Together, the team would receive the Captain Frank A. Erickson Award for exceptional performance while engaged in search and rescue operations.

“You want to chalk it up to your skill as professional military aviators,” McGinnis says. “But honestly, we also got really lucky. If just one thing had gone wrong, it would have been a disaster.… I think we were all in shock that we pulled off a miracle.”•

Julian Smith is an award-winning nonfiction journalist specializing in history, science, and travel. His work appears in Smithsonian, Wired, Outside, National Geographic Traveler, and the Washington Post. His most recent book, Aloha Rodeo: Three Hawaiian Cowboys, the World’s Greatest Rodeo, and a Hidden History of the American West, won the 2020 Oregon Book Award. He lives in Portland, Oregon, with his family.