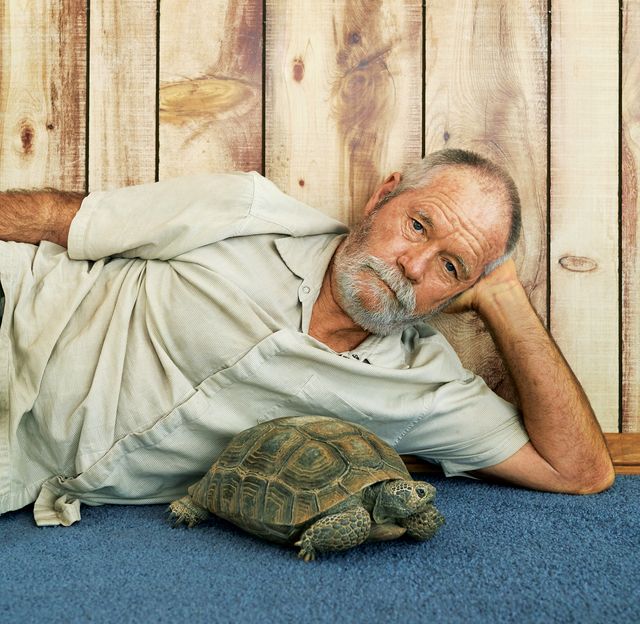

Tim Shields calls desert tortoises his “teachers” and has dedicated his life to protecting them.

Tim Shields never imagined he’d spend his days making 3-D printed tortoises that spray weaponized grape extract or standing in the desert pointing lasers at ravens, but sometimes in order to save one species, you have to go head-to-head with another one.

Shields saw his first desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) while riding in the back seat of his family’s 1957 Ford when he was about eight or nine years old. His father swerved suddenly to avoid the creature, and the young Shields braced for an impact that never came. Peering through the window, he felt relief watching the dry dome continue its slow crawl across the highway. Over the next six decades, the tortoises he encountered wouldn’t always be so lucky.

In 1979, after earning a master’s in ecology at UC Riverside, Shields began working for the Bureau of Land Management as a contract biologist. He lived in various spots throughout the Mojave Desert for months at a time, keeping cool in the dry heat by wearing a muslin smock by day and his birthday suit by night. His job was to walk across square-mile plots and count tortoises. There were so many in those days, he’d often pray not to find another one.

“I can’t even imagine that now,” says Shields, who, at 67, with his wise, weathered mug and balding head, slightly resembles the ancient reptiles he studies. Desert tortoises, he notes, have adapted impressively to their harsh environment; they can live for up to a year without water. Despite their resilience, though, there’s been an estimated 90 percent decline in the Mojave’s population since he started his work. “It was pretty weird to simultaneously fall in love with an animal and have your job be to document its extinction,” he says.

There was a two-month period in 1990 when Shields and his colleague were in the Goffs plot, a remote part of the eastern Mojave Desert, where they counted 350 live tortoises in a little more than a square mile. When he returned to the spot a decade later, he was unprepared for the massive die-off that had been caused by a respiratory disease. There were, he recalls, “30 live tortoises and 398 carcasses. Grim reaper stuff.”

Shields, who by then considered tortoises family and referred to them as his “teachers,” broke down crying.

This article appears in Issue 22 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

In 2011, the only tortoise his team spotted was a baby being carried away in the beak of a raven. That was when Shields shifted his focus from tortoises to their predators.

While many factors have contributed to the decline of the desert tortoise—respiratory ailments, drought, climate change, and habitat degradation brought on by development, agriculture, mining, off-road vehicles, and invasive plants—raven predation is uniquely pernicious because the birds target babies. A raven will flip a baby tortoise over, puncture its shell, and eat its guts. That was one threat Shields figured he could actually tackle.

As people move farther into the desert, we’re inadvertently rolling out the red carpet for ravens. Everything humans build creates opportunities for the slick black birds, whether it’s nesting spots in transmission towers or shade from an awning. More roads mean more roadkill; more development means more consumable trash. “We’re drowning in ravens here,” says Shields. “It’s not just tortoises they’re eating; they eat everything.”

One of the world’s smartest bird species, ravens can solve puzzles and remember human faces (Shields says ravens in his area recognize him). Instead of being daunted by their wiles, Shields uses their wits against them. In 2014, he founded Hardshell Labs, a company dedicated to nonlethal avian management.

One highly effective tool: lasers. Shields discovered that ravens are hypersensitive to them and that he could drive nearly all the birds from an area within four days of targeting beams at them.

Ravens also hate drones, which Hardshell Labs uses to conduct “remote egg oilings,” wherein a high-tech squirt gun shoots a thin layer of synthetic oil onto raven eggs, suffocating the embryos and tying up the reproductive energies and time of the birds still caring for the nonviable eggs.

Then there are the realistic 3-D printed fake tortoises—Techno-torts, Shields calls them—which attract ravens and are designed to counterattack. Once a raven gets close to one, Shields and his crew spray methyl anthranilate (grape extract) from inside the fake tortoise, irritating the raven, which, hopefully, will spread the word to its community that baby tortoises are off the menu.

To anyone who thinks these methods sound cruel, Shields points out that what he does is more like training ravens than outright eradicating them. If humans don’t manage the raven population, he warns, “we’re going to lose the desert ecosystem.”

A recent paper estimates that once an area has over .89 ravens per square kilometer, there will be a decline in the desert tortoise population; that density has already been reached throughout the Mojave Desert. But even though the outlook is grim, Shields is optimistic: “Tortoises have been very rare before; you don’t hang out in a place for 15 to 20 million years and not occasionally have a bad couple of millennia.”•