He may be dead by now. Either way, it doesn’t matter. I often think about people I’ve come across that, alive or dead, I won’t live long enough to see again. We were neighbors. Jimmy lived in a trailer in a little patch of woods behind Greta’s house. This was in 2008 or so. I lived in a one-room cottage on the other side of the property. Greta had built the little cottage for her son but I’m not sure he’d ever lived in it. I noticed that kids who grew up in Bolinas didn’t tend to come back. It was as if childhood in self-described Shangri-la was enough to inoculate against the myth. Richard Brautigan described Bolinas as the freeze-dried ’60s. Those of us who showed up later bought the propaganda, every bit of it, which is how it is with converts. We swallow whole. Oh, Bolinas. Utopia governed by poets. A town with a different set of principles. Anti-capitalism as a reigning philosophy. We lived it, breathed it; my god, we even believed it sometimes. And we loved our scruffy, rocky beaches, our old-fashioned general store (John’s), our comically overpriced organic co-op. Our free box (actually a shed) where you could nab a sweatshirt, work boots, used sex toys (share the love, baby), a functioning toaster, a guidebook to Thailand. Our unstaffed used bookstore where you decided what a book was worth and stuffed a dollar or two into a slot in the door. Our dim cave of a bar that opened at 9 a.m. And there was all the history, all the famous names. Brautigan—his ghost always hanging around. The man himself nearly blew his head clean off at 6 Terrace Avenue. While alive, Brautigan was so unpopular locally that it took three weeks for anybody in town to notice he was missing. By then there wasn’t much left of him. Maggots. A radio still playing. Robert Creeley, Joanne Kyger, Ferlinghetti. Tom McGuane once lived in Bolinas, as did the guy who wrote The Basketball Diaries, whose name I forget. The Grateful Dead set up shop for years in Stinson Beach, just across the lagoon. Close enough. Bob Dylan came through at least a couple of times and I once plopped down in a chair he’d sat in. I got chewed out. Nobody was supposed to sit on it ever again.

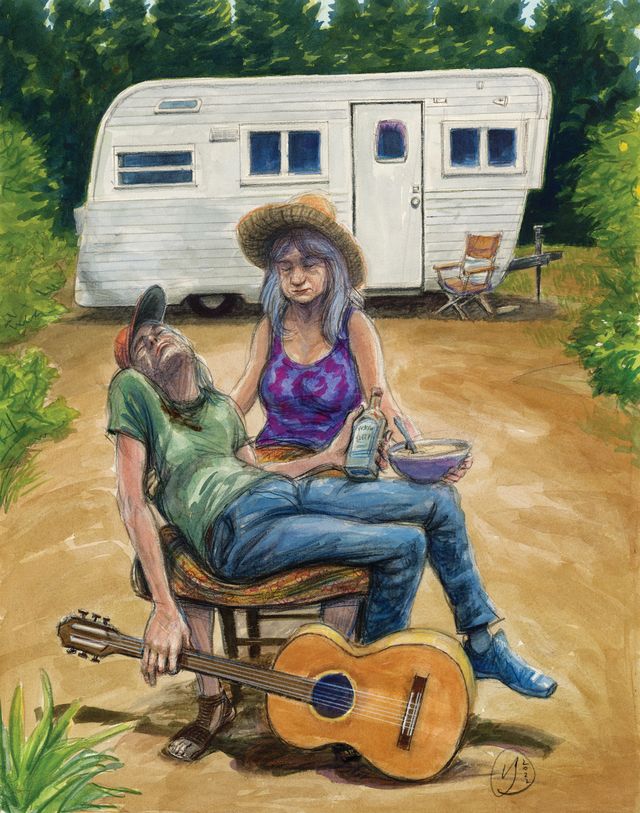

Jimmy was just another drunk who washed up on Duxbury Reef and Bolinas took him in because in spite of all the bald-faced hypocrisy, the batty real estate prices, the near-total lack of long-term rentals, it was, then, still a haven, a place that would give a drunk a 7th or 12th chance. Being unincorporated meant that nobody wielded any actual administrative power. We had no mayor, no town council, no local cops. The sheriff’s office was in San Rafael, over an hour away, depending on the traffic on Sir Francis Drake. The sole representative of civil authority was the fire chief, and she had her hands full, given that the closest paramedics were 40 minutes away in Woodacre. As a result, we had a disproportionate share of stragglers, many of whom slept under tarps on Town Beach or up on the mesa under the stand of eucalyptus between the sewer ponds and the community gardens. Jimmy got luckier than most. One night after leaving Smiley’s, he managed to stagger up Terrace to the mesa and ended up passing out in the middle of Overlook Drive. The next morning, Greta stopped and rousted Jimmy with a rubber boot to the gut and took him home. She walked him out to the trailer that had been behind her house so long she’d forgotten whose it was in the first place. Jimmy helped her drag an old piss-stained mattress from out of the garage. They managed to squeeze it through the little door, and that was that. Jimmy had his own place. A harmless, docile drunk with a guitar. A neighbor. When I saw him around the property or passed by him in town, Jimmy grunted at me, but it was a comradely grunt. He’d strum a little tune for me. He wasn’t a man with a lot of expressions. He looked my way with the same half-smile he gave everybody. And it’s true, in Bolinas, if you see people enough times, even if you never speak, there’s a connection. I had a lot of these types of friendships in those years. Intimacy without the need for conversation. Makes you feel at home to skip the talking. I long for it still.

Even after Jimmy took over the trailer, there were plenty of mornings you’d see him sleeping in the road because he couldn’t make it up to the mesa back to Greta’s. Nobody minded. We drove around him. For a while he was employed as a meat slicer at John’s. But a job interfered with his free spirit and Bolinas was all about freedom of spirit, even for those of us who worked two jobs to afford to live there. Jimmy became just another mascot in a town of mascots.

Greta would carry out hearty soup to the trailer and leave the pot on a stump with a wooden spoon sticking out. She said Jimmy was too thin. Greta took care of people. Lost souls were her specialty but she’d take care of anybody who’d let her and sometimes those who didn’t, like the dog she kidnapped from some people who had a second home on Nymph Road. Greta didn’t approve of the way its owners were treating it so, while they were out, she climbed into their house through an open window gripping a hot dog. After luring the dog home, she locked it in her house and played Tchaikovsky on her old stereo at the highest possible volume so nobody could hear the poor thing howl for mercy. Greta was an old Dutch hippie who’d fled to Berkeley when she was 18. She spoke English with militant properness, no contractions, and she’d moved up to Bolinas around the time of the oil spill in the early ’70s. The legend, and as I understand it, there’s some truth to it, was that a cadre of poets, musicians, artists, and other beautiful romantics descended on the town after a massive oil spill blackened the coastline with sludge. Dead fish, dead birds, carnage. They arrived like soldiers armed with buckets, and, the story goes, they never left. The savvy poets, for a song, bought lot after lot up on the mesa, paying a few thousand dollars on credit for a small box of land. Now the old poets, and the descendants of the old poets, are in the money, real money. Thirteen-year-old tech quadrillionaires drive up to Bo with U-Hauls full of cash. How does one point seven five sound to you for your three-room shack?

Greta was once married to a now-famous painter whose name was not uttered around town because, years earlier, he’d given up on the dream, the vision, and decamped, without Greta, back to Berkeley. In the divorce, she got the house outright. Greta herself was a sculptor. The place, inside and out, was crowded with similar-looking (Giacometti was a spiritual mentor) phallic towers, all of which, to some degree, drooped, some more than others. She sold one every once in a while to a tourist at the Saturday craft market in the community center parking lot. Mostly, though, as I say, she took care of people. Her days were spent in a bustle of urgent helping out, roaring around in her beat-up ’81 Volvo wagon with no muffler. Though the rent on her son’s cottage wasn’t cheap, far from it, Greta made soup for me, too, and delivered solicited and unsolicited life advice. I was a lost soul with a job and a half, both of which I hated.

“It is obvious that you do not follow your heart.”

“Where’s it heading?”

“See? There is your dilemma. You do not even wonder.”

Greta never laughed. Living was serious business. One was not to take this strange trip with lightness. One was not to squander the days or the nights. She was right about Jimmy, too. He was too thin and every time I saw him—and sightings were sporadic: sometimes he was around all the time, other times he’d hop on Marin Transit and disappear out of town for weeks—he always seemed to have sunk just a little bit deeper into himself. He was a big man, or at least he had been. Now Jimmy consisted of a frame with less and less inside it. Excess flesh with nowhere to go drooped off his cheeks. He had night terrors. Some nights I’d hear him clear across the property. A high-pitched screel that didn’t sound like it was coming from a human being at all. The first time I heard it I thought it had to be somebody’s cornered cat. Or maybe bats mating? It wasn’t until I went out with a flashlight that I realized the wretched noises were coming from Jimmy’s trailer. You get used to it. Jimmy’s terrors became just another sound of the night, like the ever-constant roar of the Pacific less than a tenth of a mile away.

Time felt a little different in those three years. I’m not sure I can explain it, but we lived on an island. So long as I didn’t leave, nothing needed to change. I’d have gone on like that had it been possible. A lot of us would have.

Once, Jimmy’s daughter came to town looking for him. This was close to the time I got priced out. It makes little sense, and I didn’t even speak to her, but I always conflate the two, Jimmy’s daughter’s appearance and my own being forced to leave, as if in some way she’d come looking for me also. Greta doubled the rent. She said she had to. Did I not realize that she had not sold a sculpture in months? Did I not grasp that she had no choice? She gave me a month and I decided to make the most of it by quitting both my jobs and day drinking at Smiley’s.

This story appears in Issue 22 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

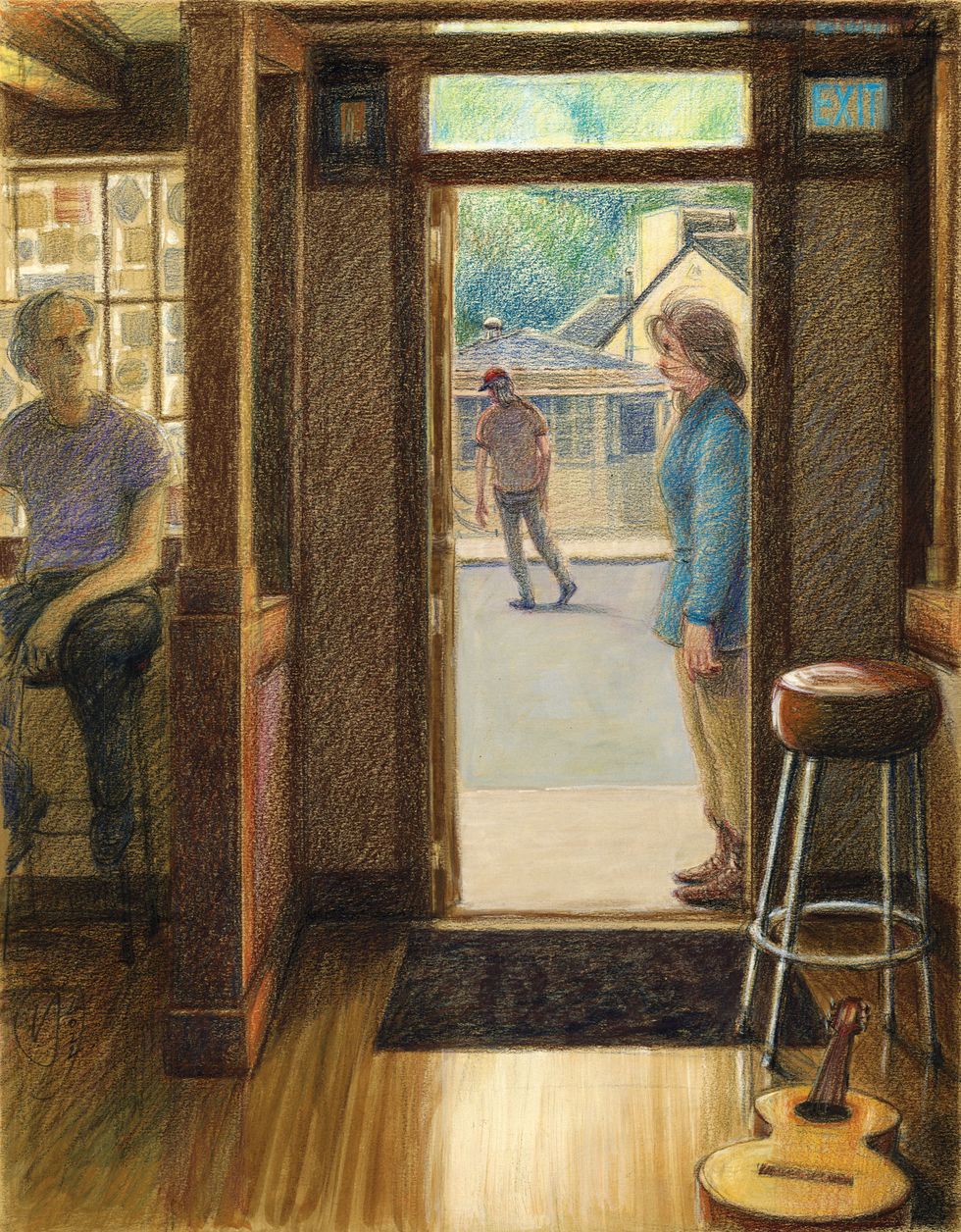

I liked to sit there and look out the open door at the light. I compared it (to myself, I never said this out loud) to an astronaut looking back at the beautiful blue pearl of Earth. Out there in the light was the street, John’s market, the park, dear life itself, while in here in the darkness was the pit we’d all end up in sooner or later.

So, I happened to be at the bar when a woman, about my age, past the cusp of 40, held up short, in mid-stride, on the threshold of the open door. For a few moments she partially blocked the light. She stared at Jimmy who was sitting where he always sat, in the tall bouncer’s chair by the door. The bouncer only worked at night. By day Jimmy owned the chair. There’s not a lot of seating at Smiley’s (eight or nine stools at the bar and nothing else), and Jimmy, by virtue of his unstinting loyalty, had earned the right to the single, special chair. He was holding his guitar. It was March or maybe April and this woman was wearing a winterish jacket because it was relatively early, before noon, and it was still cold. The four or five of us in the bar, including Jimmy and Scorno, who was tending bar that morning, were wearing T-shirts because in spite of the fact that we were all shivering life was good and we lived a carefree existence on the California coast.

Like I say it was before noon. Jimmy had already been at Smiley’s since 9 a.m. I was at the corner of the bar, closest to the window. From my angle, I was only able to get a good look at the side of her face. It was as if her eyes—I could only see her left eye, but I assumed they both had the same look of being torn open.

Jimmy, for his part, just stared at her, his half-smile stiffened in place.

“Daddy?”

Part of me, a lot of me, wanted to reach out to her, if only to touch her chin with the tip of my finger. That’s what I mostly remember, wanting to touch her from across the bar as if it was me she’d come searching for. Something about someone in their 40s saying Daddy.

“Daddy?”

After the second time she said it, Jimmy still didn’t answer. He climbed down from the tall chair and walked out of the bar. He left his guitar on the floor beside the chair. He must have set it down before he walked out. That’s when I knew he was mostly sober. Even when he was so crocked he slept in the road, he never forgot his guitar. Out the window, I watched him. I’d never seen him move so fast up the street. She stayed in the bar for a while after. She took a seat on an empty stool. Nobody bothered her. Nobody asked her any questions. The four or five of us who were there never mentioned it after. In a town where all we did was talk about each other this in itself is saying something. I wish there were more to it. There’s not. I’d make something up if I could think of anything. Scorno poured her a beer. She took a few sips. After a while she went across the street to the little park next to John’s, where she sat on a bench in the sun. At one point, she leaned over and loosened her shoes and stretched out on the bench. We watched her for about a half hour or so. Then she got into a car, a rental with Nevada plates, made a U-turn on Wharf Road, and left.•

Peter Orner’s memoir, Am I Alone Here?, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His stories have been anthologized in Best American Short Stories, and he has twice received a Pushcart Prize. He is a former member of the Volunteer Fire Department in Bolinas, California.