My guide recognizes the site from the highway, hidden by a spinney of shrubs and jimmyweed. We pull over and climb out of the dust-covered SUV. We have been traveling for two hours, searching for this location in Los Osos, near Morro Bay on California’s Central Coast. Across the road, a gust of wind escapes from the pygmy oaks in the Elfin Forest, cooling us with its breath. Turkey vultures circle above, anticipating death in the morning.

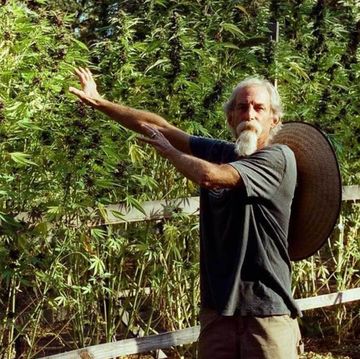

We shield our eyes from the sun and step forward, heels over gravel. Peter Alagona, a professor of environmental studies and history at UC Santa Barbara, extends his hand toward the southeast. “You probably would not have imagined it to look like this, but this is where Spanish colonists first encountered grizzly bears,” he says. Ahead of us, Los Osos Creek meanders through yellowing hills before muddying into marshland. The terrain evokes the bucolic paintings of early California, in which large predators hardly ever made an appearance.

Then I see it, about 70 yards away, hiding in plain sight: a grizzly bear on all fours.

It jars me. Then my eyes adjust—it’s just a monument, not the real thing. Painted a reddish-taupe color, the concrete grizzly blends in with the muted colors of the brush, making it hard to spot despite its size. Hunched toward the earth, it peers up with a grave, lifelike expression, as if warning us to keep a distance.

“The statue marks the spot, more or less, where the first grizzly was slain by Europeans in 1769,” Alagona says. The scene is easy to reproduce in the theater of the mind: the bucking, neighing horses, the shouts of Gaspar de Portolá’s expedition party, the muskets fired. “After the bruin was shot nine times and killed,” he continues, “the expedition smoked its meat and feasted on it.”

A year later, the mission at Monterey was founded, but it remained dependent on supplies from Mexico. In one instance, a shipment was delayed, so Junípero Serra, the founder of the California missions, dispatched Don Pedro Fages, who would later become the fifth governor of California, to return to the area where his countrymen had killed their first grizzly. Fages returned with 9,000 pounds of jerked meat taken from 30 grizzlies.

The slaughter was a grim sign of things to come. Over the next 150 years, Spanish-Mexican rancheros, fortune seekers, farmers, and trophy hunters killed grizzlies at alarming rates, at times in terribly cruel ways, such as using steel traps designed to dig deeper into a bear’s bones as it struggled to break free. The last grizzly bear in Southern California was killed in 1916 after being caught in such a trap, one that was weighed down with a 50-pound log. The female grizzly dragged the trap and log for half a mile, into the hills; when she was discovered the next day, she was still alive, and suffering. By 1924, the California grizzly (Ursus arctos californicus), a brown bear subspecies, was extirpated.

White settlers did not start to revere the California grizzly—for its size, its strength, its fierce determination to survive—until its population was decimated. The fate of the bear had been sealed, the majestic bruin reduced to an insignia on a flag.

Next to the Los Osos statue, Alagona recounts this history in a hushed tone, squinting at the hills as if grizzlies, or their spirits, still roamed in them. While he laments the bears’ demise, he situates it within a much larger story, one in which California grizzlies inhabited the state for thousands of years—and, if the right steps are taken, may do so again.

Alagona leads a team that has included nearly 50 archaeologists, wildlife biologists, ecologists, and other scientists whose aim is to promote more informed conversations about the “past and potential future of grizzly bears in California.” Aptly named the California Grizzly Research Network, the multidisciplinary group plans to conclude its work in 2025. Yet Alagona believes that its findings to date, which have identified suitable reintroduction sites and food systems, suggest that grizzly bears could be brought back. “Grizzly bears are like the Swiss Army knives of bears,” he says with a smirk. “Drop them off in most environments and they’ll survive. The bigger question is whether or not people will tolerate them.”

Bear State Reaction

Typically, wildlife issues cleanly divide proponents and dissenters. The issue of reintroducing the grizzly bear to California, however, is a bit more hairy. Where people can rally behind efforts to preserve the California condor or protect wild mustangs (even as the latter ravage grasslands throughout the West), Californians of all political persuasions and lifestyles are hesitant about bringing an apex predator—one that can weigh up to 900 pounds and take down a full-grown moose—to a state bursting with 40 million people. Ranchers, especially those in areas where wolves have returned, are deeply concerned about the possibility of adding grizzly bears to the mix.

“The Whaleback wolf pack up in Siskiyou County has already had six confirmed cattle kills in recent months,” says Kirk Wilbur, vice president of government affairs for the California Cattlemen’s Association. “The question emerges: Is cattle ranching still viable in northeastern California?”

He adds, “Urban and suburban environmentalists who will not be impacted by this are more than happy to have their rural neighbors bear the brunt of reintroduction.… If this were formally proposed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, we would strongly oppose it and leave everything on the table in terms of stopping it.”

If the grizzly were to be brought back to remote areas of the state, the way Californians experience the outdoors would change on a fundamental level. Imagine hearing the huff of a grizzly bear outside your tent at night or spotting a huge brown mass moving toward you on a remote trail.

“We already have conflicts with mountain lions and livestock and humans…and now we’ve got wolves. To think about bringing another predator into the state that we would have to manage and come up with some program to figure out what happens when the grizzly attacks a human or kills livestock does not seem feasible for us,” says Jordan Traverso, deputy director of communications, education, and outreach at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “With wildfires erupting throughout the state, there are enough issues to solve. Why do this now?”

This article appears in Issue 23 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

It’s a question that Alagona is more than keen to answer. Next year marks the 100th anniversary of the last credible grizzly bear sighting in California, and many environmentalists believe it should be commemorated with a plan from U.S. Fish and Wildlife for the bruin’s return, especially now that a number of Indigenous tribes, including the Tejon and the Yurok, are considering the possibility.

Tiana Williams-Claussen, the Yurok Tribe’s Wildlife Department director, says that the Yurok want to see the restoration of species that existed on their land before European contact, because these creatures played a critical role in the environment. However, the Yurok interpret their land to be in a state of imbalance at present. “An apex predator would either improve or worsen that situation,” says Williams-Claussen. “It could be beneficial: we have more black bears than the land can support, and elders have said that Grizzly once helped keep those populations in balance. But we no longer have the abundance of deer, elk, and fish we once had; their habitats are too far degraded.” She adds, “It’s an interesting question, can or should this be done?”

Alagona maintains that if Indigenous tribes were to favor the idea, it would be an ethical imperative to bring back the grizzly. At its core, the notion of reintroduction involves philosophical questions about the land: To whom does it belong, and how should it be used?

While grizzly bear numbers have increased from fewer than 1,000 to more than 1,800 in the contiguous United States since they were classified as a threatened species in 1975, the remaining populations, such as those in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, are isolated, dangerously so.

“If we’re serious about recovering grizzly bears, we need more populations around the West, and more connections between them so they don’t fall prey to inbreeding and have a chance of adapting to a warming world,” wrote Noah Greenwald in 2014 on behalf of the Center for Biological Diversity, the Arizona-based conservation organization where he is the endangered species director. “Grizzly bears are one of the true icons of the American West, yet today they live in a paltry 4 percent of the lands where they used to roam.”

Despite their threatened status, the federal government has tried to strip protections from grizzlies on several occasions, such as an attempt in 2012 to allow seasonal hunting of the bears. The pushback from wildlife advocates was fierce, including a lawsuit the Center for Biological Diversity brought against U.S. Fish and Wildlife that petitioned for the grizzly bear to be returned to areas within its historical range.

The attempts to remove the grizzly’s threatened designation, the ensuing lawsuit, and the overall hoopla have generated public interest in reintroduction efforts, especially in California. Seven years after the lawsuit was filed, the federal government issued a report acknowledging that the High Sierra would provide suitable habitat for grizzly bears but stating that it would not begin the reintroduction process because the grizzlies in California would be isolated from other populations across the West—the very point that Greenwald raised years ago about the Yellowstone grizzlies.

The Center for Biological Diversity’s effort to have the grizzly bear’s historical range recognized by the federal government has seemingly reached a stalemate, but the reality is that U.S. Fish and Wildlife could decide at any time to green-light a reintroduction project. If it did, the groundwork conducted by Alagona and the California Grizzly Research Network would most likely make California among the federal government’s first testing sites. “California is actually a wildlife-friendly state. If there were a state to reintroduce grizzlies, it would be the one,” says Greenwald.

Until then, however, scientists must address the “reintroduction gap.”

Cohabitating with Carnivores

Once we leave the statue in Los Osos, Alagona drives five miles up the coast toward Morro Bay. While Portolá journeyed via land from Baja to California, many of his soldiers sailed to Morro Bay and then marched south to join his ranks. We are roughly following, albeit in reverse order, the path that these conquistadores traveled. Our plan is to observe a few areas, such as the hills east of Los Osos and Sedgwick Reserve, where the ecosystems have remained similar to what the Spanish encountered. It’s not something easily done elsewhere in the state.

Since Portolá’s expedition, the majority of California’s landscapes have been dramatically altered. While the California condor was extinct in the wild for 5 years, nearly 100 years—too much time, in the eyes of some researchers—have passed for the grizzly. The conceptual distance between current social and physical conditions and ones that are suitable for grizzlies to reinhabit, what scientists dub the reintroduction gap, is quite wide. This leaves reintroduction proponents with the complex task of determining whether suitable homes for grizzlies still exist and, if so, how to rank them.

Rachel Mazur, who oversaw the bear management program in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks for nine years, discounts the entire reintroduction project. In the first chapter of her book Speaking of Bears: The Bear Crisis and a Tale of Rewilding from Yosemite, Sequoia, and Other National Parks, widely considered an essential work on black bear stewardship, she writes frankly about grizzly bears coming back to the Golden State: “The political reality is that people are afraid of grizzlies, and the ecological reality is that the habitat has been converted to agriculture and cities, including Fresno and Merced.”

In the SUV, Alagona concedes that Mazur may have a point, but California is a massive state. “We have plenty of space,” he says. “The question is whether or not we want them. And it is a choice.”

When considering a potential reintroduction site, the California Grizzly Research Network looks for blocks of unbroken wilderness (owing to the grizzly’s proclivity to wander and the dangers of inbreeding), abundant food resources, and areas with little human traffic. The High Sierra, the mountain range containing Yosemite and Kings Canyon National Parks; the Shasta Cascade, in the state’s northeastern corner; the Trinity Alps, the second-largest wilderness area in California; and the Los Padres National Forest, just east of Santa Barbara, all meet such qualifications.

Ironically, Alagona looks to the land of the colonizers—Europe—as a model for human–brown bear coexistence. The continent is only slightly larger than the Lower 48, yet 17,000 brown bears roam there, more than nine times as many as in the contiguous United States. And it’s not only bears that are thriving in the Old World. Wolves, lynx, and wolverines are rebounding in impressive numbers from the Fennoscandian peninsula to the Mediterranean. A 2014 article in Science reveals that such conservation success is a result not of setting aside swaths of land for animals (Europe has very limited space to devote to wilderness and more than twice the population of the United States) but of a changing mindset toward cohabitating with large carnivores. Europeans are increasingly more open to sharing spaces with bears and other predators; they recognize the integral roles these creatures play in various ecosystems and how, in the long run, animal biodiversity benefits humans as well.

One key difference, however, is that while Europe may have brown bears, the grizzly bear subspecies lives only in North America, and the California grizzly, now extinct, lived only in the Golden State. If the brown bruins are to return to California, they must be brought from elsewhere in the country.

With wild grizzlies living only in Alaska, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and western Canada, the options are limited and must be weighed carefully, as the grizzlies in each region have evolved over millennia to exhibit unique behaviors and seek specific foods. Determining which grizzly would adapt best to California requires extensive multifaceted research, not least of which is figuring out what constituted the California grizzly’s diet.

The Fossil Record Roars

Months before the road trip to Morro Bay, I visit the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles. Fog floats over Wilshire Boulevard. It’s an unusually cold morning, even for January. As I take in the drama of the site’s iconic mastodon statues crying out to their companion mired in the Lake Pit, Alexis Mychajliw, a paleontologist, conservation biologist, and assistant professor at Middlebury College as well as a research associate with the Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County, informs me that I’m looking at a former mining site that has since filled with rain, mud, and asphalt. “It’s more like a dirty lake than anything else,” she says. “But don’t worry. We’ll get to observe some of the real tar pits.”

I turn to face the museum behind us, a megalithic-looking compound with a frieze depicting prehistoric animals snarling, eating, and chasing one another. Mychajliw speaks in a relaxed voice, enunciating every syllable as she walks toward the open green lawns that lead away from the lake and the museum: “I want you to see the pits outside; then we’ll visit the Fossil Lab inside the museum.” Researchers have excavated the remains of around 2,500 saber-toothed cats and more than 3,600 dire wolves from the local pits, but they have lifted only a handful of bears from the gloopy earth. The reason, I guess somewhat correctly, is that most bears were too clever to get caught. “Maybe they also weren’t scavenging as much as we think something like the dire wolf and saber-toothed cat that was attracted to those sites did,” Mychajliw says.

We tread through damp grass until we reach Pit 10, which looks like a small pond caked in muck and leaves. Below this layer, its black sludge swallowed a slew of exotic beasts, including a California grizzly that was discovered in 1914. An examination of the bones and later radiocarbon dating indicated that the bear was a small female that lived around 6,000 years ago. What caused the female grizzly to risk entering the tar is unknown: it could have been a desperate act to retrieve food or to rescue a cub, but the bones have yet to tell that part of the story. What they do reveal, however, is what the California grizzly ate.

I follow Mychajliw back toward the museum and into the Fossil Lab, where scientists hunch over microscopes and stride from desk to desk with specimens in gloved hands. It feels like a scene from Jurassic Park except that some of the creatures being examined still exist. Mychajliw calls me over to a large back room with shelves full of fossils and other specimens. She picks up the skull of the California grizzly bear we were discussing and, surprisingly, lets me hold it. The side of the skull reads, in white print, “Pit 10.”

Mychajliw explains that she is working on a complex biochemical analysis of the bears’ bones to learn about their diets. “Essentially, you are what you eat,” she quips.

Gleaning such knowledge is crucial for deducing which habitats might support California grizzlies today. Findings by Mychajliw and her team so far indicate that California grizzlies, whose bones were sampled from across the state and from varied climates, mostly ate an herbivorous diet: roots, shoots, berries, and other vegetation as well as copious amounts of acorns. Grizzlies at the northern end of California feasted on more salmon and trout than those farther south; at higher elevations, the bears tended to feed on more carrion.

The researchers have discovered that the California grizzly increased its meat consumption after the Spanish arrival but not enough to significantly alter its nutritional intake. The slight change appears to have been the bruin’s way of adapting, not a mark of its genetic expression. As its habitat was transformed into farms, and as feral pigs—parting gifts from the Spanish—destroyed oak groves through excessive rooting that decimated the once-abundant acorn supply, the grizzly augmented its diet.

Yet the sizes of these grizzlies were consistent over time, which indicates that the bears were not hypercarnivorous, as historical reports often maintained. If they had eaten as much livestock as was claimed (in one account, a grizzly was purported to have killed 200 sheep in one flock), California grizzlies would have been much larger, something akin to the Kodiak bears of Alaska. Instead, California grizzlies were comparable in bulk to their largely herbivorous Wyoming cousins.

It’s highly possible, then—in the event that U.S. Fish and Wildlife includes California in its updated recovery plan—that a sleuth of Yellowstone grizzlies could land a one-way ticket to the West Coast. And it wouldn’t be the first time bears were reestablished in the state.

Consider that 35,000 black bears live in California, the most of any contiguous state. Yet the bruins spotted on Big Bear hiking trips or making headlines for splashing into families’ pools in Pasadena are not exactly native to Los Angeles and San Bernardino Counties. Black bears existed in the region thousands of years ago, but for unknown reasons, they died off before humans arrived.

According to a fish and game journal published in 1935, the president of the California Fish and Game Commission put in a request for some of Yosemite’s black bears. Since the park had a surplus at the time, 28 of them were translocated to the Greater Los Angeles area, where they have since thrived and multiplied. It was a reintroduction.

A Sacred Kinship

Five months after visiting the La Brea Tar Pits, I travel to Yosemite National Park with The Sacred Paw, Paul Shepard and Barry Sanders’s exhaustive book about bears in nature and myth. The name Yosemite is a derivative of the Ahwahneechee word uzumati, which signifies “grizzly bear.” Both the Indigenous group and the bears are absent from here.

Devlin Gandy, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and a PhD candidate in archaeology at the University of Cambridge, sees a connection in their disappearances: “I really see the loss of the California grizzly as just another extension of genocide, spreading into the ecosystem.”

Gandy specializes in paleoenvironmental genomics, a field complementary to paleontology that analyzes ancient DNA to construct accurate renderings of past environments and societies. He is preparing for his most ambitious project to date: a yearslong study with the California Grizzly Research Network that seeks to help California tribes regain ecological, cultural, and traditional knowledge bases that may have been affected by or lost to colonization.

Gandy believes that the grizzly could be a key to unlocking collective memories for the tribes that live in areas of California where the bears once roamed. “We’re still in the initial stages of this project, so we’re clarifying what working with our tribal partners will look like and what they will want from this collaboration,” Gandy says over Zoom.

Participating tribes will have the opportunity to examine what the bear still means to them and how its return could help them better understand their land. For instance, in arboreal settings, grizzlies cleared debris to create meadows and make paths in the forest, which in turn mitigated the destruction from nature-caused fires; in more arid or desert areas, the bears dug for water during droughts, creating arroyos that revitalized plants and sustained other wildlife; and, of course, they dispersed seeds through their scat, increasing plant diversity.

Because of these ecological benefits, and others that have yet to be rediscovered, many California tribes consider the bears to be teachers or land ambassadors; some see them as reincarnated forms of their grandparents. Gandy explains that speaking about the relationships between the California grizzly and Indigenous people in past tense is a bit of a misreading of how Natives view the bear: “For a lot of the tribes, the bear is still alive. It may not be physically here, but it still spiritually is alive. It’s part of their daily prayers. It’s part of their culture. It’s an omnipresent being whether or not it’s physically here.”

The most tangible demonstrations of this belief are the prayers that California tribal elders, and a growing number of people from younger generations, still offer to the grizzly. Gandy politely declines to say which tribes recite the chants as he does not have their consent to do so. However, non–tribal members can witness the Tachi Yokut Tribe’s ceremonies in which a handful of individuals are chosen to dress as grizzlies and dance before their communities.

“Bringing the bears back is truly an aspect of healing,” Gandy says. “It’s a form of healing for the land and its people.”

Bear in Mind

Back on the Central Coast, Alagona and I leave Morro Bay and head south toward the Los Padres National Forest, making a quick detour at Sedgwick Reserve, in the San Rafael Mountains. Managed by UC Santa Barbara, Sedgwick is a 5,896-acre nature reserve and a site where the California Grizzly Research Network has conducted some of its experiments. I want to see a bit of the landscape and flora that were used in the group’s research, so we decide to hike through an oak savanna. A graduate student we meet at the research facility tells us that a mountain lion was spotted the day before at the water hole where we’re headed. Alagona seems unfazed, so we press on.

I keep my eyes peeled on the hills, but my mind circles back to a gnawing problem: if grizzlies return to California, it will be only a matter of time before a human-bear conflict occurs. Going to Yellowstone and encountering a grizzly is very different from living in an area where the bears are being reintroduced. It’s highly possible that someone will get maimed or lose their life.

Alagona acknowledges right away that a grizzly bear attack could happen, but he explains that if outdoors enthusiasts give the bruins space, store their food responsibly, and hike in groups, the brown bears will leave them alone. Appearing somewhat unsatisfied with his answer, he adds, “We tend to think that the outdoors exist purely for our recreation. The reality is that we share this planet with other species, and none of its environments, especially wilderness areas, were meant to be safe. The national parks were not made to protect us—they were meant to protect wilderness and animals from us.”

The Spirit of the Grizzly

Back on the road, Alagona points the SUV in the direction of our final destination: a mountain lookout above the Los Padres National Forest. In the stretch of nine hours, we have visited the site of the first encounter between Europeans and grizzly bears, traced a portion of Portolá’s land expedition, and hiked through an area similar to what the grizzly bear may lord over if it returns.

An hour after we leave Sedgwick, the sides of the mountains turn golden under the fat sinking sun. The hum of the engine makes me want to doze off, but Alagona perks up as we inch closer to Los Padres. Out of the four sites that the California Grizzly Research Network is considering for reintroduction—the High Sierra, the Shasta Cascade, the Trinity Alps, and Los Padres—the last is Alagona’s favorite. Los Padres is a vast wilderness area, he says, more than twice the size of Yosemite. It contains everything in terrain and resources that the grizzlies would need to survive, including incredibly diverse plant life.

One big unknown is how the Los Padres climate—not nearly as cold as Wyoming’s—would affect the hibernations of reintroduced grizzlies. Warmer winters would certainly equate to shorter hibernations, but that is not to say the change would necessarily be negative. Brown bears in parts of Alaska hibernate for nearly seven months; black bears in Mexico do not go into full hibernation. Yet both thrive in their environments. The only way to know for certain how grizzlies would acclimate is for them to set their paws in California.

Alagona has no doubt that grizzlies would do well with either normal or short hibernations: they’ve survived other environmental regime transformations. “Brown bears essentially came to California with us, with humans, around the end of the Pleistocene, or the last Ice Age,” he says. “They could have also come early during the Holocene, which means they would have shared environments in Eurasia with us for a long time and adapted to varying climates. The short-faced bear reigned in California during the last Ice Age, but the grizzly bear endured with us and then became the dominant bear in California—until very recently.”

He taps his fingers on the steering wheel as if tallying the 99 years that have passed since its extinction. “The story of brown bears in California is really the story of people in California.”

I roll down the window and let the fresh mountain air rush inside. It’s humbling to think of how long brown bears shared habitats with humans even before crossing into this continent, even before evolving into a distinct subspecies and becoming grizzlies. In each epoch, humans would have interacted with them, weaving their experiences into the grander story of man and bruin. It’s regrettable that this tale ended in California before today’s generations could contribute to it.

Attitudes toward wildlife are changing, however, and not just in California but across the country. President Joe Biden’s America the Beautiful initiative aims to conserve 30 percent of U.S. lands and waters by 2030, which has earned it the tag “the 30x30 initiative.” The multipronged undertaking was written “to conserve, connect, and restore the lands, waters, and wildlife” of the United States while soliciting the help of tribal nations in guiding the endeavor, signifying a profound shift in perspective on the land and whom it belongs to. Then there’s American Prairie, a project that seeks to preserve the Northern Great Plains of Montana by connecting more than 3 million acres of private and public land in a vast unbroken chain of wilderness. So far, American Prairie includes more than 450,000 acres. If authorized, the reintroduction of grizzlies to California might also set the stage for other conservation measures, especially the plan to restore jaguars to the American Southwest.

“The two best reasons for bringing back the grizzly is that the natural world is in a state of systemic collapse, and we need to be doing everything to restore and shore up wildlife populations and ecosystems while we still can,” Alagona says. “The second is that the destruction of the grizzly was really a war waged against native California and Native Californians. This means that no program of social justice for the crimes of the past will ever be complete until we all reckon with the destruction of nature in general and bears in particular.”

As we’re driving along East Camino Cielo, Alagona rolls the SUV to a stop yards away from a bluff, and we’re met with the view of an opposing mountainside. Clambering out of the vehicle, I move toward the edge of the crag. The ravine below, which is part of the upper Santa Ynez River valley, runs northeast into the heart of the Los Padres backcountry in a series of folds, like fat wrinkles on the back of a dog’s neck.

Wind surges from beneath and offers the sharp, minty smell of sage. Across the gorge, lush with chaparral, pines, and herbaceous vegetation, the mountain rises from shadows to reveal a craggy face glimmering with emerald-looking streaks. Closer to us, the berries of manzanita and the leaves of oak trees are visible, foods for the California grizzly bear of the past, and maybe of the future.

I recall Mychajliw telling me, “The resources are available for grizzlies to thrive in the state.”

Alagona’s claim that the story of brown bears in California is the story of humans in California makes the landscape appear empty, even haunted. The thought that brown bears lived in this land for millennia beside humans, only to perish within a reckless period of less than 150 years, is damning.

Before I turn away from the valley, another draft rushes upward, carrying the scent of sage but also a musky fragrance. The mingling of the two is intoxicating: in that moment, I imagine that the land is yearning for the grizzlies’ return. Standing on this precipice, it certainly seems as if one of them could be down below.

And making that happen certainly seems worth a try.•

Ajay Orona is an associate editor at Alta Journal. He earned a master’s degree from USC Annenberg’s School of Journalism in 2021 and was honored with an Outstanding Specialized Journalism (The Arts) Scholar Award. His writing has appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books, Ampersand, and GeekOut.