I: THE MAN

It’s a real sanctuary, the first I’ve discovered since fleeing my birth den and journeying miles and miles through the most alien, booby-trapped hellscape you can imagine.

Sure, there’s danger here, too. I’m hemmed in on all sides of this tiny wilderness by fast-moving rivers of metal. And my new dominion’s overrun with that loud, smelly species I avoid at all costs.

But the humans and cars mostly melt away at night, and there are ravines to hide in. And deer. So many deer.

I leap onto their backs from a stealth position low in the bushes, their flesh yielding under my claws, their necks snapping like dry branches. How I feast!

Before dawn, I drag their carcasses off the trails and cache them under soil and leaves, returning for three nights while the meat remains fresh.

By day, I lie up in remote canyons.

When the sun falls, I rise to feed or hunt again, to scent mark and explore the contours of my strange new world, sending out chirps and cries for others of my kind that get no replies.

Then comes the night that changes my world and yours.

It’s winter. Still newly arrived, I’m prowling a hillside trail, my excellent night vision and hearing alert for prey.

Snap, and something grabs my paw. I yank hard, but I’m trapped.

Humans approach.

A loud pop. A sting. My head droops. My limbs buckle. I hit the ground and spin into the void.

Do big cats dream?

Do we twitch with nightmares of alpha predators that even we cannot vanquish?

This article was featured in Alta Journal's free Weekend Read newsletter.

SUBSCRIBE

Six times in my life, I’ll face the same nightmare and one man in particular: a powerful magician armed with a bewildering weapon against which teeth, claws, and stealth are useless.

In my black swamp of terror, paralysis, and wrongness, I am poked and prodded. Something is placed around my neck. My eyes are closed, but I see my adversary. His eyes flare with the same intensity that I turn on the deer I stalk.

But there is no death in his eyes.

Six times, this man will resurrect me, and I’ll lift my groggy head to find them standing around me. My only instinct that of flight, I’ll stagger to my paws and plod unsteadily away into the brush.

Then comes our seventh and last encounter.

This one will have a different ending.

II: WAKE

A remote den in the western Santa Monica Mountains. It’s lined with moss or other vegetation—a pile of rocks, a thicket, a hillside crevice. It’s 2010, probably spring or summer, and a mountain lion has just given birth to a litter of cubs. Their father is P-1, the first puma collared in Southern California. He’s long gone, since mountain lions are solitary and meet only to mate.

P-1 has been closely monitored and studied by wildlife biologists, providing a trove of knowledge about the lives of these reclusive beasts. In scientist circles, P-1 is famous, the first in his line of collared cats. But take another look at those blind, mewling, one-pound newborns in that long-ago den. One of them will survive incredible odds, dodge danger every day of his life, embark on a perilous quest, discover a new kingdom in an urban wilderness in the middle of Los Angeles called Griffith Park, and far eclipse his father in fame when his mythical story captures the hearts and imaginations of millions. He will become an icon and symbol of wildlife conservation. He will become P-22.

Even in the womb, P-22’s survival was precarious.

Cars are the top killer of Southern California’s pumas—they claimed the lives of five big cats in 2022 alone, including a female pregnant with four cubs who was killed crossing Las Virgenes Road near Calabasas. Necropsies showed rodenticides in the blood of mother and fetuses, potentially fatal poisons that travel up the food chain and cross the placenta.

P-22’s mother isn’t run over, killed by rodenticide, or slain by another lion—a third danger. She lives to nurture her cubs into adolescence. Still, they’re vulnerable to predators whenever she leaves to hunt. That’s why nature endows P-22, and all puma newborns, with camouflage: black stripes and spots that fade to beige at six months.

At first, his mother brings home meat. By the six-month mark, when the cubs are weaned, she has begun teaching P-22 and his siblings to hunt. They start with small prey like skunks and rabbits, then graduate to deer. Fifteen months pass. P-22 is now an adolescent.

It’s time to establish his own territory or die, because older males already claim his birthplace. The signs abound: Claw marks on tree trunks. Scent marking. The “scuffs” in which males claw up dirt mixed with urine and feces to claim their range.

But where can P-22 go?

One male puma can roam 150 square miles, and the Santa Monica Mountains span only 300 square miles. Plus: they’re encircled by development, freeways, and ocean. Most young males here don’t live past two; they’re killed by older lions or by cars if they flee across highways. In urban areas, they risk being shot, like the young male puma who ventured into downtown Santa Monica in 2012 only to be killed by police.

Territory is a particularly acute problem for P-22, whose father, P-1, was a big, aggressive dude, even by cougar standards. He was a “vicious individual” who killed other males, his offspring, and even his mates, according to Miguel Ordeñana, the wildlife biologist who will discover P-22.

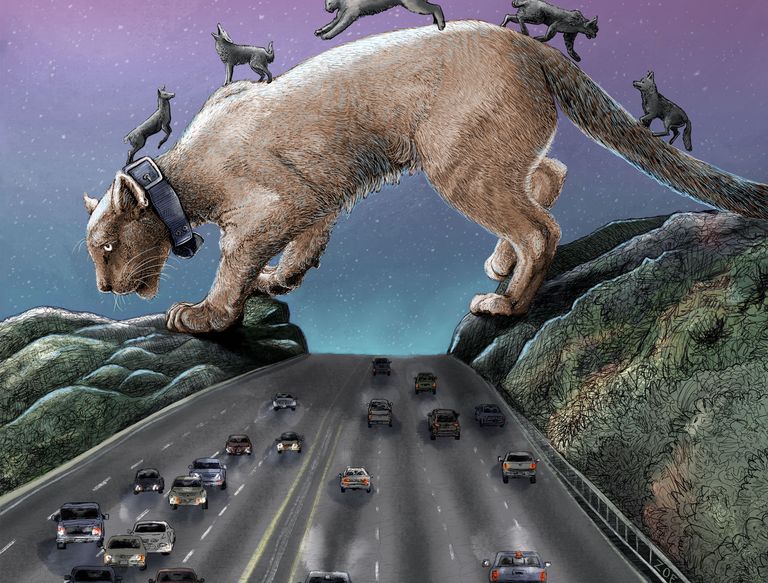

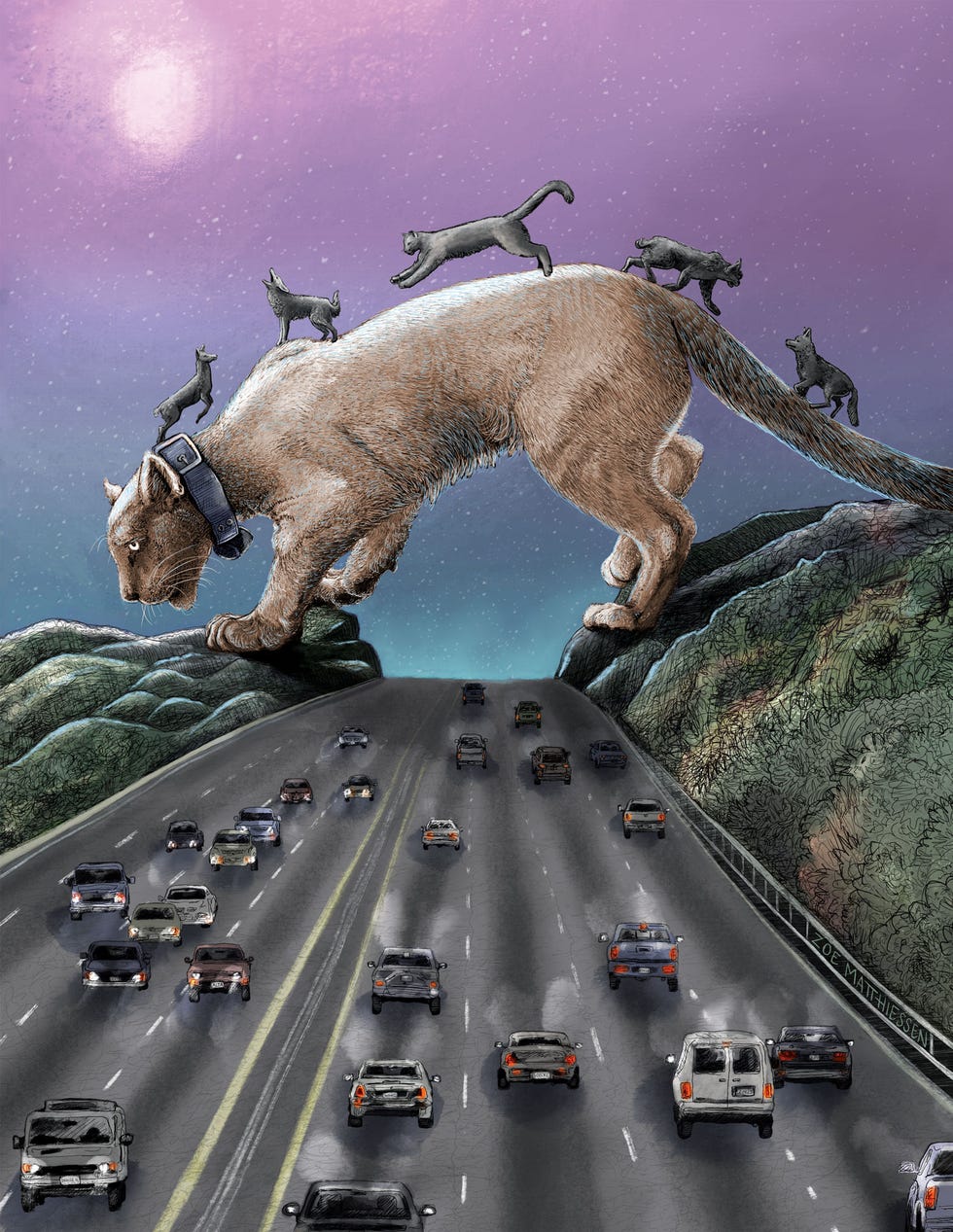

In 2011, P-22 leaves his home. He travels east until he reaches the hills overlooking the 405 freeway, which smells evil and poisonous, its cars whooshing past at terrifying speeds. Somehow, he crosses—a feat that stumps biologists, whose wildlife-monitoring cameras at street bridges and tunnels capture not one image of the milestone.

P-22 continues east, probably hugging dense green space and unused land, keeping to less well-lit neighborhoods, traversing backyards, hillsides, drainage ditches, and the lethal speedway of Mulholland Drive. He slips unnoticed through Bel-Air, Beverly Glen, the Hollywood Hills. In early 2012, he meets another seemingly insurmountable obstacle: the 101 freeway. Eight lanes of traffic, but nary a wildlife camera records his passage into Griffith Park.

A ghost cat.

A ghost cat whose days of obscurity are ending.

III: THE SURVIVOR

Time stamp: February 12, 2012, 9:15 p.m.

I feel safe moving along the animal trails amid the dense brush and trees around the lake they call the Hollywood Reservoir. But that’s an illusion, because suddenly my paw is seized in a trap. Fear floods me. It doesn’t hurt, but I can’t get away. Across the mountains, a device owned by the Man rings.

A small group gathers under the stars to examine me with wonder and awe: the first live mountain lion ever found in Griffith Park. As I stare nervously back, the Man knocks me out with a dart gun.

With lamps strapped to their heads and gloves on their hands, they poke a needle into my flesh and draw blood. They weigh and measure, examine my long, curving teeth, tag my ear, stick a thermometer up my butt. In later encounters, I’ll be shot full of vitamins, have my GPS batteries swapped out, and be healed of sickness. But for now, I’m a healthy “subadult” two-year-old male who weighs 121 pounds and stretches six and a half feet from muzzle to tail tip.

A one-pound radio collar made of polyurethane, plastic, and metal is placed around my neck. Eight times a day, my location will be beamed to orbiting satellites, which will relay my coordinates back to the Man.

They also name me. I’m P-22, the 22nd puma collared in the Santa Monica Mountains, whose eastern boundary is Griffith Park, my park.

As dawn breaks, an antidote wakes me, and the humans step back. I stand, take a few wobbly steps, and vanish into the chaparral. But I don’t leave the safest place I’ve ever found.

I settle in.

Los Feliz, Hollywood Hills, Lake Hollywood, Forest Lawn, the hills above Universal Studios and Warner Bros., the golf courses and horse trails, the mortuaries and the L.A. Zoo: Nightly, I patrol my dominion in my slouchy model stroll, searching for ladycats, hunting, and scrupulously avoiding the loud, smelly species. In our rare encounters, I am timid, not aggressive. I hunt deer, which is most of my diet, with a sprinkling of coyotes and raccoons. No pet dogs—except one, unleashed, found wandering in my park. Tastes like coyote.

That’s how my days go until I develop mange, a parasitic skin disease that can kill. Weakened, I lose weight, and my face becomes grotesquely disfigured, my once-fluffy tail thin as a rope. It may have been a rodenticide-tainted animal I ate. The Man captures me again, treats me with vitamin K and topical medicine. They say two of my puma compatriots died despite treatment, but I recover.

There’s a house near the park whose cellar I like to slip into to snooze the day away. One day, workmen arrive, see me, and run out screaming. Believe me, I’m not thrilled either. More humans come. They pummel me with tennis balls and poke me with sticks to get me out. Nope. Not moving. A crowd gathers on the street, but the Man is not among them. I hunker down. It’s a standoff. Late at night, when they finally leave, I flee back to my park.

The zoo intrigues me greatly. So many animals. Such interesting smells. With my long hind legs and powerful haunches, I can easily clear the eight-foot-tall enclosure. One night, koala is on the menu. For a similar transgression, one of my brethren—P-56—pays the price and is shot. For some reason, the zoo spares me.

My most famous nocturnal sojourn is a routine but apparently memorable one: a photographer has hidden a camera that captures me predawn, staring ahead as I pass a famous sign that also lives in the park.

Afterward, my fame skyrockets, as the loud, smelly species says. I inspire an annual park festival, fundraisers, bills to outlaw rodenticides, a future wildlife crossing, social media accounts.

But the big cat stays wild, and life for me is fending off one threat after another.

I’m constantly dodging cars and people. I’ve never found a mate. My territory is less than one-twentieth that of a typical male cougar. Each raccoon or other small meal is a rodenticide gamble that could kill me.

The passage of years erodes my strength. Sometimes my insides don’t feel right. Taking out a mule deer now takes it out of me.

One spring night, I leave my park and range farther than ever before, to the domain of Silver Lake, where small wild prey abounds. When a car approaches, I crouch in my trademark cougar defensive position until it passes. Humans see me, too, but we ignore each other as always.

By fall, I haven’t given up on deer, but each kill is harder. One night, I spot a small dog walking on a leash near Lake Hollywood. Instinct and hunger take over, and I snatch it. But I need to eat 30 pounds of meat a day, and hunger gnaws at me. I lose weight, grow weaker. I try to grab another Chihuahua in Silver Lake, but its owner pummels me, and I let go.

I’ve always avoided people and leashed pets, stuck close to my wild park. But my behavior is changing, and I’m risking more encounters with humans. Do I pose a danger to them as well as to myself?

In the weeks before the winter holidays celebrated by humans, I’m crossing Los Feliz Boulevard early one night when I hear a screech, then a crash that knocks me down.

Pain. Terror. Confusion.

Everything hurts.

I rise and stagger into a courtyard. Humans follow me, and I flee again.

Must find shelter.

My head throbs, clouding my thoughts. Instinct leads me to a familiar backyard. On this overgrown quarter-acre hillside where I feel safe, I’ll rest and recover. But maybe I’ve returned here to die.

IV: SLUMBER

At 10:15 a.m. on December 12 of 2022, Jeff Sikich, a wildlife biologist with the National Park Service at Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, who for years has managed all fieldwork on big cats, pulls up to a Los Feliz home.

Sikich’s colleague knocks on homeowner Sarah Picchi’s door and explains there’s a sick mountain lion in her backyard. Picchi, who’s following the saga like so many Angelenos, knows it’s P-22. The cougar has visited her home before.

Aided by his telemetry receiver, Sikich hikes up the muddy hillside and heads right for P-22. Two other biologists fan out in case the sick cat runs.

P-22 doesn’t flee. He lies there and waits for Sikich, the Man who for a decade has been his nemesis, advocate, and caretaker. As Sikich draws close, the big cat rises, but only to hide behind a tree, which leaves his haunch exposed.

The tranquilizer dart sounds like an air gun.

Soon the litter bearers appear, carrying an unconscious P-22 in a green tarp, his fur stuck with twigs and wet leaves.

The somber procession files down the hillside, and Picchi sees the puma’s chest rising and falling. His eyes are closed. As Sikich performs a health check, Picchi notes the respect and compassion he displays toward the cat. Like they’ve known each other a lifetime. Which they have.

P-22 is placed inside a large metal box with air holes and taken to the L.A. Zoo he once explored, then the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, where he is examined by veterinarians who specialize in large cats. A metropolis of 10 million waits.

When test results arrive, they’re dire. P-22 has a skull fracture and severe internal injuries. He has a torn diaphragm and herniated organs protruding into his chest cavity, probably from the car crash. Kidney failure, advanced liver disease, heart disease, and a widespread parasitic skin infection. He’s lost a quarter of his body weight.

This article appears in Issue 23 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

Five days after his capture, doctors make the excruciating decision to euthanize P-22, the puma who changed lives and civic attitudes about conservation. A $100 million wildlife crossing over the 101 in Agoura Hills wouldn’t be under construction without him.

Beth Pratt, California regional director of the National Wildlife Federation and a longtime advocate for P-22, sits near him. She tells him he is a very good boy.

Later, a new sound will rise from the assembled wildlife experts, one P-22 has never heard before from the loud, smelly species.

It is the sound of crying.

V: THE GHOST

My body is brought to L.A. County’s Natural History Museum, accompanied by the one who first discovered me on a wildlife camera, Miguel Ordeñana.

We are met by descendants of many tribes of Indigenous people, on whose land my ancestors once roamed and were revered.

The tribal leaders, who recite a blessing for me, want to see me buried in my park, where I once reigned as king. Where I belong.

Will the spirit of L.A.’s Ghost Cat haunt Griffith Park?

It already does.•

Acknowledgments

Yes, this story does take some liberties in having P-22 narrate his own story. Everything stated is, however, based on extensive research, reporting, and interviews with humans who played important roles in P-22’s life. Particular thanks to:

• Jeff Sikich, a wildlife biologist with the National Park Service at Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, who captured P-22 seven times between 2012 and 2022 and knew the big cat better than anyone.

• Wildlife biologist Miguel Ordeñana, now senior manager of community science at the Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County, who first spotted P-22 while reviewing wildlife-camera footage in 2012. This wasn’t his job; it was a labor of love for Ordeñana, who grew up across from Griffith Park.

• Sarah Picchi, the Los Feliz homeowner to whose backyard P-22 fled—for the last time—after being hit by a car. After his final capture, Picchi shared her photos of P-22 widely with the media.

Denise Hamilton is a Los Angeles native, crime novelist, and former reporter for the Los Angeles Times. She’s the editor of Los Angeles Noir and Los Angeles Noir 2: The Classics and was a finalist for the Edgar Award. Read more about her at denisehamilton.com.