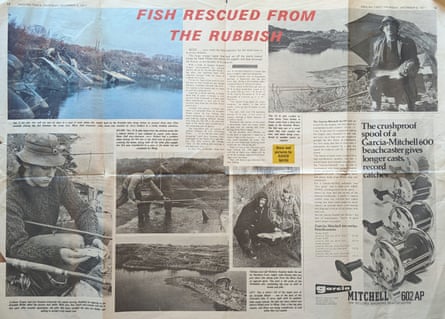

In 1971, the Angling Times sent reporter Dave Nash to document a disaster in Ockendon, Essex. The resulting article described the extinction of a local beauty spot, hundreds of hectares of open space where former gravel pits had become popular fishing lakes. “In less than a decade, what was one of the best fisheries in Essex has been savagely raped and despoiled. Seven hundred tons of household garbage is deposited into the pits every day, along with a similar undisclosed amount of industrial refuse.” The article was accompanied by a striking picture, taken by Nash, showing two men attempting to catch a pike between the scrap cars that lined the bank of Arisdale lake. “If it’s not the water level dropping,” said Jerry Hulbert, the vice-president of the Moor Hall and Belhus Angling Society, “then it’s the rubbish encroaching a few feet every day.”

I came across this story via my father-in-law, Cliff Hatton, who had sent me the newspaper cutting in the post. He would often tell me how the gravel pits, clay pits and sand pits of South Ockendon – initially dug out by the Ham River Grit company to feed the post-second world war hunger for concrete in south-east England – became, in his own excited words, “a nirvana” once they had naturally filled with water. “You dig a hole in Thurrock, leave it a few years and there are fish in it.”

The faintly absurd happenstance of the pits felt to me like a classic Essex story. My birth county had long made the best out of whatever the modern world threw at it, from industrial growth along the Thames to postwar new towns, becoming a shorthand for a loutish brand of greed-is-good Conservatism in the 1980s, and spray-tanned reality stars in the 2010s.

Like many former Londoners looking for green space, Cliff’s family had moved to South Ockendon from a housing estate near Romford in 1964, when Cliff was 11. He and his older brother Barry were keen fishers, and had enrolled in the local angling society. They rejoiced at the abundance of water they could dip their lines into. Cliff was a big fan of local heroes the Small Faces and the music of the burgeoning 1960s mod scene, which was filling Mecca ballrooms with R&B and soul from Forest Gate on the edge of London to Clacton on the coast. But it wasn’t music that kept him up all night. While his peers might have been trying their luck with a potential squeeze in the dark corner of a parquet-floored hall, he was sitting under the moonlight with a rod, eager to catch a handsome carp, perch or bream.

Cliff said one of the pits, known as Hamble Lane, had, like an increasing number of places in south Essex, become an established rubbish tip by the time they started fishing there. But, while fishing at night, he noticed something odd. “There was more activity at the site during the hours of darkness than there was during the hours of light, even though everybody should by law have been gone,” Cliff said. Lorries would come through the gates “nose-to-tail” with sometimes up to 14 in a convoy, all through the night until sunrise. It was only later he realised the extent of the industrial chemicals that were being dumped there under cover of darkness.

One day in 1967, an elderly neighbour had asked Cliff to bring back some sticks from the Hamble Lane dump that he could use in his rose garden. Cliff remembered his errand when he was on the way back from fishing, after the sun had gone down. He climbed on top of a pile of wood to search for sticks, and then jumped off. “I just leapt into the darkness thinking I was going to land on solid ground,” said Cliff. Instead, he found himself up to his waist in slime. After a few moments, his skin began to burn. He had jumped into a caustic slurry, dumped there by a pharmaceutical company based in Dagenham. “That led to me spending a week or so in hospital and many, many weeks after that invalided indoors with great burns to my legs and on my face,” said Cliff.

Cliff’s parents, knowing their place, never sought compensation. Once recovered enough to return to the pits, Cliff found two half-empty drums of granulated cyanide floating in one of them. Another time, he and his brother came across a mountain of glass vials, and suspected that barbiturates had been dumped a few yards from a school fence. “We took some samples to the local police station, and showed them these dangerous drugs and mentioned they were within yards of the school playing field, and the only question we were asked was: ‘What were you doing over there?’ They were more worried about the fact that we were trespassing.”

Thurrock council took no action over the scandalous pollution that burned him and destroyed the habitat he so cherished, leaving Cliff with “a lifelong grudge against authority”. Decades later, he still winced at the thought of the fish floundering about in a couple of feet of muddy, poisoned water as the pits were drained and the whole reserve became a landfill site; those that hadn’t already perished were buried alive under tonnes of industrial waste.

“And of course with them went all the voles and the birdlife, including kingfishers and bitterns.” Each time Cliff told me of his favourite fishing spot, the Ripples, it was as if he could see it before him anew. “It was dubbed the Ripples because when the wind blew on it and the sun shone on it, it was such a beautiful looking place. It sparkled. It was a paradise and it just went under a sea of filth.”

I wanted to delve further into Essex’s tales of dumping, so I went to visit a couple of historic landfill sites in East Tilbury on the Thames coastline at Thurrock, at the invitation of Prof Kate Spencer, an environmental geochemist at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL). Spencer has dedicated more than a decade to studying the threat of coastal landfill, concentrating much of her research in south Essex. There are about 50 historic landfill sites in the Thames estuary area (out of 1,215 around England’s coast), but of the Essex sites, only Thurrock is eroding: a large bank of rubbish, supposedly safely buried, now spilling its guts on to the beach and into the Thames at an alarming rate.

As we walked along the beach at the edge of a decommissioned landfill site, the waste-strewn shoreline seemed to carry on for ever, with sheets of asbestos lying over bottle caps and shards of glass softened by the attention of the tides. Cascades of ragged plastic in off-white, black and grey had been spewed out of the bank of earth, a layer cake of soil and rubbish, with plastic mingling in the thickets of brambles and green vegetation to become almost indistinguishable from it. Almost.

Spencer and QMUL have analysed materials at this site and others in Essex and the Thames estuary and around the country. “It’s definitely contaminated,” she said. Once the landfills are full, they are capped with a layer of earth, but levels of contamination “would breach human health guidelines”. Proponents of capping have long promised that it would be the end of the problem, but Spencer is compelled to keep reminding people that, oh no, it isn’t.

She pointed to the different potential sources of toxicity just lying around on the beach. Old car batteries leaking cadmium. Bottles of medicine. Domestic waste, commercial waste, including many, many different types of fabric, which Spencer suspected had been chucked away by east London textile companies. For ages, she said, there was a big clod of fabric that had long ago been shredded and was coming out of the earth along with little pink cotton reels.

Spencer started her journey by analysing the toxicity of these kinds of landfill sites and their effect on the surrounding salt marsh habitats at a site on the Medway estuary, on the other side of the Thames. She took what is called a “sediment core from the riverbed, a sample that captures the depth of different layers, preserving the sequence of the deposits. This helped her dig into the records of historical pollution. The result was a kind of palimpsest of London’s industrial boom. “You are going back down into history and you can see how the quality of the river changed. The Thames was polluted noticeably from the 1820s and 1830s and it reached a big peak in the late 1800s. You can imagine, the Industrial Revolution, lead smelting, and all that kind of thing. Then mid-20th century, post-second world war, in big cities like London there would be a huge population growth, [more] industrial growth. You can see the water quality deteriorate, and that is recorded in the sediment.”

In one way or another, the story of Essex is a story of a great population swell in the county’s southern reaches, in part as the county has long fulfilled a role as a repository for the people (and their waste) that London doesn’t have the space for. In 2015, during excavations at Liverpool Street station, 3,300 skeletons were discovered at the site of the old Bedlam psychiatric hospital. There was no room left in London’s cemeteries, and so they were commuted to Canvey Island, east of Tilbury on the Thames estuary.

Spencer said it would have been a really easy decision to send rubbish from London to the Thurrock tip: “Put it on a barge, ship it down here.” In the 19th century, east London authorities or vestries such as Mile End bought up land in Essex with the intention of using it to bury their rubbish. As Lee Jackson recounts in his history of the filthy capital, Dirty Old London, a London county council official in the late 1800s described the reason for using Essex as a place to dump waste: “The natural solution is to shoot it in some sparsely inhabited district, where public opinion is not strong enough to effectually resent it being deposited.”

The erosion of landfill into estuaries is not a problem exclusive to Essex. It’s just that Essex happens to be next to the UK’s capital, and so its landfills tend to be super-sized. Mucking Marsh in Thurrock was one of the largest landfills in western Europe, taking on 660,000 tonnes of rubbish from the dustbins of London each year, brought downriver on barges every day before dawn. “It could be seen from space,” said Graham Harwood, a Goldsmiths academic and artist based in Leigh-on-Sea. He and his wife, Matsuko Yokokoji, run the art initiative YoHa, whose work delves into the Essex estuary’s hidden and sometimes malignant past.

An academic he may be, but after decades on the Essex coast, Harwoood has acquired the slightly grizzly air of the seafarer. He told me he was interested in “the philosophy of waste”. Despite the horror they can inspire, dumps had a “magical quality” to them, he said. A sort of 21st-century sublime. He wanted to see public assemblies between local politicians, young people, activists and retired tip-workers, who know what kinds of toxicity are buried in the landfills. He wanted to set up “dialogues about the haunting of waste in the future. Think, the worst has already happened, so what can we do with this.”

For Harwood, key to understanding the Essex marshes is the concept of “wasteland”, which is central to the county’s place in the world. He told me that when Europeans first went to the Americas and found land no one was farming, it was called wasteland. “This idea of waste is so kind of fixed in our culture, and it’s so embedded in colonialism as well. And so you can see the way that London has used Essex as a kind of colony … sending out vast tracts of shit.”

Pitsea was an old Victorian marshland tip off the A13 near Basildon, where no one ever knew exactly what was being dumped. One of the former tip-workers I met told me it was later discovered that the soil in some of the places he worked was contaminated with “arsenic, strychnine, who knows what”. In 1975 a lorry driver, Thomas Carroll, died after inhaling lethal hydrogen sulphide fumes given off by two toxic loads dumped in Pitsea, which made the press across the UK. Reporting on the story, the Daily Mirror called Pitsea “the bin of Britain”.

Spencer said the process of dumping and capping reminded her of her grandmother who, when she got dementia, started to hide things that upset her, like old clothes or dirty dishes, putting cushions over them or placing them in cupboards. Until around the 1970s, Spencer said, dumping legislation was thin on the ground, with few records of what was being dumped and where. “The idea was, this is the end of the road for the rubbish,” said Spencer. ‘We have put it in a hole in the ground, covered it up and that problem has now gone away. But we now realise we haven’t put it away. We’ve just been storing the problem.”

Earlier, as we walked downhill from the train station to the East Tilbury landfills, Spencer had stopped to show me the stark geological differences created by rubbish. We gazed south-west towards a stretch of coastal landfill known as Bottle Beach. Spencer pointed out a long strip of land that was much higher than the marsh. “That landscape shouldn’t look like that,” she said. “If you’d gone back 150 years, we would have just been looking at a flat marsh, your kind of Charles Dickens Great Expectations salt marsh. It should have just been completely, completely flat.” Spencer said if you drive out of London on the A13, as you head east, you should be able to see the river, as you are driving along the floodplain. “But you can’t. You’re seeing a whole landscape of landfill.”

For me, the marshes of Essex feel akin to its soul. When I think of home, the first things I picture are these uncategorisable plains of spongy vegetation that could seem menacing in the right light, with reeds and samphire sprouting from a dark, glistening mud, where wading migrant birds stalk on the lookout for food. Grassy sea walls. Reclaimed munitions dumps. Flat fields with pillboxes and all that mud. A terrain sliced by creeks, accented by sluices and characterised by a great gloop that can remind folk that they are never far from the primordial.

And yet, the ambiguity and unstable nature of once-malarial marshlands led to their ruin. On a family picnic one beautiful and hot spring day on Two Tree Island, a nature reserve at the edge of the Thames estuary, my three-year-old daughter, Greta, kept asking “What’s that?” whenever she spotted the thick brown bottoms of beer bottles, 1980s Tesco bags or old shoes – so many shoes – protruding out of the dry ground. It was a surreal detail from a pleasant trip that I might once have laughed off, but now, accompanied by my children, it felt like a bad dream.

In some places, however, the matter that London no longer wanted has been used in productive and creative ways. An artificial hill in an old metropolitan Essex area of east London, formed from a huge heap of toxic spoil dumped by the old gas works, has been known for years as the Beckton Alp. Its most imaginative use was as a dry ski slope, opened in 1989 by Diana, Princess of Wales.

The RSPB used more than 3m tonnes of material excavated from Crossrail’s tunnel digs to raise part of Wallasea Island at the mouth of the Thames by an average of 1.5 metres, transforming farmland into a coastal marshland haven for egrets and oystercatchers and creating lagoons across 670 hectares.

Mucking Marsh was named a site of special scientific interest in 1991, owing to the populations of shelduck, grey plover, dunlin, black-tailed godwit and redshank that roosted on the salt marsh, and the abundance of vegetation such as sea purslane and sea aster, not to mention rare spiders, but it continued to be used for rubbish disposal until 2012. (A third of all coastal historical landfills are located near designated ecological sites.) Mucking’s conversion into a nature reserve, which was opened by David Attenborough in 2013, was partly financed by almost £3m in funds from DP World, the Dubai-owned company that built the London Gateway port nearby, and Enovert, a waste management company that used to use the site for dumping. The site at Pitsea is earmarked to be transformed by the RSPB in the next decade.

Further east, the landfill site at Two Tree Island in Leigh-on-Sea was converted back into public land in the 1970s. Now blackberries, apples, pears, damsons, plums and cherries all grow here. People come to swim in the water at Leigh, where there are also wild food foraging clubs. A local chef, John Lawson, has written about how his love for foraging was ignited by sourcing samphire fresh from Two Tree Island. But Spencer was alarmed by environmental reports for Two Tree Island that identified cyanide on the site. She didn’t even want to take samples back to the lab.

In 2017, Spencer wrote a report with her colleague at QMUL, Dr James H Brand, on the risk of pollution from historic coastal sites at risk of flooding or erosion for the Environment Agency, based on research into Leigh Marsh, used as a site for dumping between 1955 and 1967, and Hadleigh Marsh just a little way west, which was active during the 1980s. They analysed waste and soil-like material from the landfill. Some of the samples were found to have lead concentrations more than 12 times the recommended level for good ecological health.

Leaching of chemicals and other harmful substances from landfill is liable to increase with sea level rise. But it isn’t just coastal erosion that is breaching the deposits of trash. It is the effects of curiosity, too. Bottle Beach is popular with the mudlarking community, a burgeoning group of amateur historians and curious walkers who come and dig through the rubbish, burrowing holes into the scrub to find trinkets. We came across old 20th-century booze and medicine bottles in lines, as if they had been filed for consideration by a digger but didn’t make the final cut. There were certain people Spencer saw regularly “sitting in a toxic hole” eating sandwiches after digging like a mole into heavily contaminated earth with no gloves on. “‘Well, I’m fine,’ they’d say. ‘I’ve been doing it since I was a kid.’ But then asbestos takes 40 years to take hold.”

The rubbishscapes of south Essex entwine with memories the same way microplastics leaching out of landfill are said to have done with the fibres of our bodies. When my wife’s grandfather died, his funeral was at Bowers Gifford, one of the highest points of south Essex. As I followed the hearse into the crematorium, the enormous capped mound of rubbish at Pitsea came into view. Most people glide past these vistas on the train without a second glance, but I began to obsess about them. On the train out to meet Spencer, I had marvelled at the Pitsea horizon, a nonsensical Thames estuary hillside towering over the mudflats, a Brecon Beacon of waste. Coming to places like Tilbury and Mucking made me feel as if I was very much living in the Age of Consequences.

After 10 years looking at the landfill problem, Spencer couldn’t see many obvious or workable answers. “The solution seems to be: ‘Don’t worry about it until something happens.’ It’s shameful. And there’s a moral issue – it’s no different to throwing your rubbish out of your car window. Your car’s clean … ”

The issue is slowly picking up traction in the places that count, but with the emphasis on “slowly”. Spencer was on an expert witness panel for a UN rapporteur in 2017, a report into the impacts of toxic waste in human health in the UK, but five years on she said she is still waiting for the UK government’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs to develop a clear strategy to assess the impact of these sites.

One of the big things that has changed in recent years is that marsh landscapes are now valued. The Thames estuary and many other Essex marshes are protected wetland sites, and could even soon become Unesco world heritage sites. Marshes store carbon, purify water, provide valuable habitat and act as a natural buffer against coastal erosion. The Environment Agency would like to turn some of the farmland adjacent to the former East Tilbury landfill site back into salt marsh to provide habitats for wildlife and storage for flood waters with sea levels rising, but the presence of waste is complicating those plans.

I headed back to East Tilbury station, passing the unusually high banks of rubbish one last time, and pondered that if the county’s brash, Thatcherite caricature “loadsamoney” was the front, then its waste mountains were the back. If Essex marshes were once seen as out-of-the-way places that you could quite easily get away with dumping in, it now fell to far-off countries such as Malaysia to receive our waste. The postwar boom in consumer goods in the late 20th century resulted in enormous amounts of household waste, and we will all leave our own hill of trash. In making visible this hidden toxic legacy, coastal erosion, while potentially tragic, could have a positive effect. After decades of using Essex as a dumping ground, people can finally see the scale of the challenge.

This is an edited extract of The Invention of Essex: The Making of an English County, published on 1 June by Profile Books and available to order at guardianbookshop.com